Cheese enzymes play a crucial role in the cheese-making process, but their classification as dairy can be a subject of debate. While these enzymes are commonly derived from animal sources, such as rennet from the stomach lining of ruminants, they are not inherently dairy products themselves. The primary function of cheese enzymes is to coagulate milk, separating it into curds and whey, which are then processed into cheese. Although they originate from animals, enzymes like rennet and microbial alternatives are typically considered processing aids rather than dairy ingredients. This distinction is important for individuals with dietary restrictions, as the presence of cheese enzymes in a product does not necessarily indicate dairy content, especially when microbial or plant-based enzymes are used.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Source of Enzymes | Cheese enzymes can be derived from animal (dairy), microbial, or plant sources. |

| Dairy-Based Enzymes | Rennet (chymosin) is a traditional dairy-based enzyme extracted from the stomach lining of ruminant animals (e.g., calves, goats, sheep). |

| Microbial Enzymes | Non-dairy alternatives include microbial enzymes produced by bacteria, fungi, or genetically engineered microorganisms (e.g., recombinant chymosin). |

| Plant-Based Enzymes | Some enzymes, like those from figs or thistles, are plant-derived and dairy-free. |

| Dairy Content in Cheese | Cheese enzymes themselves are not dairy, but if derived from animal rennet, they are associated with dairy. Microbial or plant-based enzymes are dairy-free. |

| Labeling Requirements | Products using animal-derived enzymes may be labeled as containing dairy, while those using microbial or plant enzymes are often labeled as dairy-free or suitable for vegetarians/vegans. |

| Allergenicity | Dairy-based enzymes may pose risks for individuals with dairy allergies or intolerances, whereas non-dairy enzymes are generally safe for these groups. |

| Vegetarian/Vegan Status | Cheese made with animal rennet is not vegetarian/vegan, but cheese made with microbial or plant enzymes is typically acceptable for these diets. |

| Common Usage | Microbial enzymes (e.g., recombinant chymosin) are widely used in modern cheese production due to consistency, cost-effectiveness, and dairy-free status. |

| Regulatory Classification | Dairy-based enzymes are considered dairy products in some regions, while non-dairy enzymes are not. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Enzyme Role in Cheese Making: Enzymes like rennet coagulate milk, essential for curd formation in cheese production

- Dairy Origin of Cheese Enzymes: Most cheese enzymes are derived from animal sources, primarily dairy animals

- Non-Dairy Enzymes in Cheese: Microbial enzymes offer dairy-free alternatives for vegetarian or vegan cheese production

- Lactase in Cheese Making: Lactase breaks down lactose, reducing dairy sensitivity in certain cheese types

- Enzyme Impact on Flavor: Dairy enzymes influence cheese texture, aroma, and taste during aging processes

Enzyme Role in Cheese Making: Enzymes like rennet coagulate milk, essential for curd formation in cheese production

Cheese making is a delicate dance of science and art, where enzymes play a starring role. Among these, rennet stands out as the unsung hero, transforming liquid milk into solid curds through coagulation. This process is not just a chemical reaction but a pivotal step that determines the texture, flavor, and overall quality of the cheese. Without enzymes like rennet, cheese as we know it would not exist.

Consider the precision required in using rennet. Typically, 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon of liquid rennet is diluted in 1/4 cup of cool, non-chlorinated water for every 2 gallons of milk. This mixture is then gently stirred into the milk, which has been warmed to around 86°F (30°C). The milk must sit undisturbed for 4 to 12 hours, depending on the desired cheese type. For example, softer cheeses like mozzarella require less coagulation time, while harder cheeses like cheddar need more. Overuse of rennet can lead to a bitter taste, while too little results in a weak curd that won’t hold its shape.

The role of rennet extends beyond mere coagulation. It selectively cleaves the protein kappa-casein, releasing para-kappa-casein, which stabilizes the curd and allows whey to separate efficiently. This specificity is why rennet is preferred over acidic coagulants like vinegar or lemon juice, which produce a less consistent curd structure. For those avoiding animal-derived products, microbial rennet offers a dairy-free alternative, though it may yield slightly different results in terms of texture and flavor.

Understanding the enzyme’s function also highlights its dairy-specific nature. While rennet is derived from animal sources (traditionally from the stomach lining of ruminants), its action is entirely focused on milk proteins. This means that while the enzyme itself is not dairy, its role is exclusively tied to dairy processing. For lactose-intolerant individuals, it’s important to note that most cheese made with rennet contains minimal lactose, as the curdling process removes much of the milk sugar.

In practice, mastering rennet usage is key to successful cheese making. Beginners should start with simple recipes like ricotta or paneer, which use heat and acid for coagulation, before moving to rennet-dependent cheeses. Always use a thermometer to monitor milk temperature and a timer to track coagulation. Experimenting with different rennet types—animal, microbial, or vegetable—can also yield unique results. Ultimately, the enzyme’s role in cheese making is both precise and transformative, turning humble milk into a culinary masterpiece.

American Cheese Slices: Unveiling the Milk Content Mystery

You may want to see also

Dairy Origin of Cheese Enzymes: Most cheese enzymes are derived from animal sources, primarily dairy animals

Cheese enzymes play a pivotal role in the transformation of milk into cheese, acting as catalysts that break down proteins and fats to create the desired texture and flavor. While some enzymes are plant-based or microbial, the majority used in traditional cheesemaking are derived from animal sources, specifically dairy animals like cows, goats, and sheep. This dairy origin is rooted in historical practices and the natural presence of these enzymes in animal tissues, particularly in the stomach lining of ruminants. For instance, rennet, a complex of enzymes crucial for curdling milk, is traditionally extracted from the fourth stomach chamber of calves, kids, and lambs. This reliance on dairy animals underscores the deep connection between cheese production and animal agriculture.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the dairy origin of cheese enzymes is essential for consumers, especially those with dietary restrictions or ethical concerns. For example, individuals following a vegan diet must avoid cheeses made with animal-derived enzymes, opting instead for alternatives like microbial or plant-based rennet. Similarly, those with lactose intolerance or dairy allergies need to scrutinize labels, as even small amounts of animal-derived enzymes could trigger adverse reactions. Manufacturers often specify the source of enzymes on packaging, using terms like "animal rennet" or "microbial enzymes," allowing consumers to make informed choices. This transparency is critical in a market where dietary preferences and restrictions are increasingly diverse.

The use of dairy-derived enzymes in cheesemaking also raises questions about sustainability and ethical practices. While traditional methods rely heavily on animal sources, modern advancements have introduced alternatives that reduce dependence on animal by-products. Microbial enzymes, produced through fermentation of bacteria or fungi, offer a more sustainable and animal-friendly option. However, these alternatives may not replicate the exact flavor profile achieved with animal-derived enzymes, leading to debates about authenticity versus ethics in cheesemaking. For artisanal producers, balancing tradition with innovation is key, as they strive to meet consumer demands while maintaining the integrity of their craft.

For home cheesemakers or those curious about the process, experimenting with different enzyme sources can provide valuable insights into how they influence the final product. For instance, using animal rennet typically results in a firmer curd and a more pronounced flavor, while microbial enzymes may yield a softer texture and milder taste. Dosage is critical—too little enzyme can prevent proper curdling, while too much can lead to a bitter flavor. A common starting point is 1 drop of liquid animal rennet per gallon of milk, though this varies based on milk type and desired cheese variety. Practical tips include ensuring the milk is at the correct temperature (typically 86–100°F) and allowing sufficient time for the enzymes to act, usually 30–60 minutes.

In conclusion, the dairy origin of most cheese enzymes highlights the intricate relationship between animal agriculture and cheesemaking. While this tradition continues to dominate the industry, the rise of alternative enzyme sources reflects evolving consumer preferences and ethical considerations. Whether for dietary, ethical, or experimental reasons, understanding the source and function of these enzymes empowers individuals to make informed choices and appreciate the complexity behind every bite of cheese.

Delicious Chicken Stuffed with Broccoli and Cheese: A Tasty Dish Explained

You may want to see also

Non-Dairy Enzymes in Cheese: Microbial enzymes offer dairy-free alternatives for vegetarian or vegan cheese production

Cheese production traditionally relies on rennet, an enzyme complex derived from the stomachs of ruminant animals, which coagulates milk to form curds. However, for vegetarians, vegans, or those with dietary restrictions, animal-derived rennet is a non-starter. Enter microbial enzymes—a dairy-free alternative that mimics rennet’s function without animal involvement. These enzymes, sourced from fungi, bacteria, or genetically engineered microorganisms, offer a precise and ethical solution for curdling plant-based milks or dairy milk in vegetarian cheese production. For instance, *Rhizomucor miehei* and *Aspergillus oryzae* are commonly used microbial sources, providing enzymes like chymosin and proteases that effectively coagulate milk proteins.

The process of using microbial enzymes in cheese production is straightforward but requires attention to detail. Dosage is critical—typically, 0.005% to 0.01% of the enzyme preparation is added to the milk, depending on the desired curd firmness and type of cheese. For vegan cheese, where plant-based milks like soy, almond, or coconut are used, microbial enzymes must be paired with additional coagulants like calcium chloride to achieve the right texture. Temperature control is equally important; most microbial enzymes work optimally between 30°C and 40°C (86°F to 104°F). Overheating can denature the enzymes, while underheating slows the coagulation process, so monitoring is essential.

One of the key advantages of microbial enzymes is their consistency and reliability. Unlike animal rennet, which can vary in potency due to biological differences, microbial enzymes are standardized, ensuring predictable results batch after batch. This makes them ideal for large-scale production of vegetarian or vegan cheeses. Additionally, microbial enzymes are often more cost-effective than traditional rennet, especially as demand for dairy-free alternatives grows. For small-scale producers or home cheesemakers, pre-measured enzyme powders or liquid solutions are available, simplifying the process and reducing the risk of error.

However, it’s important to note that not all microbial enzymes are created equal. Some may impart a slight off-flavor if not used correctly, particularly in delicate cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta. To mitigate this, producers can opt for highly purified enzyme preparations or blend microbial enzymes with other coagulants. For vegan cheese, combining microbial enzymes with ingredients like agar-agar or tapioca starch can enhance texture and flavor. Experimentation is key—start with small batches to fine-tune the enzyme dosage and coagulation time before scaling up production.

In conclusion, microbial enzymes are a game-changer for dairy-free cheese production, offering a versatile and ethical alternative to animal-derived rennet. Whether you’re a commercial producer or a home enthusiast, understanding the nuances of these enzymes—from dosage and temperature control to flavor considerations—can help you create high-quality vegetarian or vegan cheeses. With the right approach, microbial enzymes not only meet dietary needs but also open up creative possibilities for innovative, plant-based cheese varieties.

Exploring the Diverse World of Cheese Varieties and Origins

You may want to see also

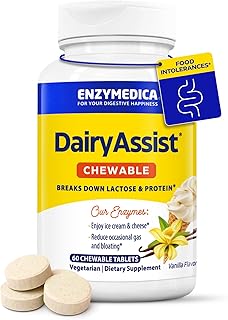

Explore related products

$15.99

$6.5

Lactase in Cheese Making: Lactase breaks down lactose, reducing dairy sensitivity in certain cheese types

Lactase, the enzyme responsible for breaking down lactose, plays a pivotal role in cheese making, particularly for individuals with dairy sensitivity. During the cheese-making process, lactase can be added to milk before fermentation, effectively reducing the lactose content in the final product. This enzymatic action converts lactose into simpler sugars—glucose and galactose—which are more easily digestible. For example, cheeses like cheddar, Swiss, and Parmesan naturally contain lower lactose levels due to the fermentation process, but adding lactase can further minimize lactose, making these cheeses even more tolerable for lactose-intolerant individuals.

From a practical standpoint, incorporating lactase into cheese making requires careful consideration of dosage and timing. Typically, 0.05% to 0.1% lactase by weight of milk is added at the beginning of the process, allowing sufficient time for lactose breakdown before coagulation. This method is particularly useful for soft cheeses, which retain more lactose compared to aged varieties. For home cheese makers, lactase drops or tablets can be used, with dosages adjusted based on the milk volume and desired lactose reduction. However, it’s crucial to monitor the process closely, as over-addition of lactase can alter the texture and flavor of the cheese.

Comparatively, lactase-treated cheeses offer a middle ground between traditional dairy products and lactose-free alternatives. While lactose-free milk is completely devoid of lactose, lactase-treated cheeses retain some lactose but at levels low enough to be well-tolerated by many. This approach preserves the natural characteristics of cheese, such as its creamy texture and complex flavor profile, which are often lost in fully lactose-free versions. For instance, a lactase-treated mozzarella can still melt beautifully on a pizza, unlike some lactose-free alternatives that may lack the desired stretchiness.

Persuasively, the use of lactase in cheese making opens up a world of possibilities for those with dairy sensitivity, allowing them to enjoy a broader range of cheeses without discomfort. Studies show that individuals with mild to moderate lactose intolerance can tolerate up to 12 grams of lactose in a single sitting, which is roughly the amount in a cup of milk. By reducing lactose content through lactase treatment, cheeses like Gouda or Brie can become accessible, providing both nutritional benefits and culinary enjoyment. This innovation bridges the gap between dietary restrictions and culinary desires, making cheese a more inclusive food choice.

In conclusion, lactase in cheese making is a game-changer for dairy sensitivity, offering a practical and effective solution to reduce lactose content without compromising quality. Whether you’re a professional cheese maker or a home enthusiast, understanding the role of lactase and its application can transform your craft. For consumers, opting for lactase-treated cheeses can mean rediscovering the joy of dairy without the digestive drawbacks. With precise dosing and thoughtful application, lactase ensures that cheese remains a staple in diets across the spectrum of dairy tolerance.

Provolone Cheese Nutrition: Calories, Protein, and Health Benefits Explained

You may want to see also

Enzyme Impact on Flavor: Dairy enzymes influence cheese texture, aroma, and taste during aging processes

Cheese enzymes, derived primarily from microbial, animal, or plant sources, are undeniably dairy when sourced from animals, such as rennet from calves. However, their role extends beyond categorization—they are the silent architects of cheese flavor. During aging, enzymes like lipases and proteases break down fats and proteins, releasing volatile compounds that define a cheese’s aroma and taste. For instance, lipases hydrolyze milk fats into free fatty acids, contributing to the tangy, nutty notes in aged cheeses like Parmesan. Understanding this enzymatic alchemy reveals why a single type of milk can yield vastly different cheeses depending on enzyme activity.

To harness enzyme impact effectively, consider dosage and timing. Lipase, for example, is typically added at 0.1–0.5% of milk weight for mild flavor enhancement, while higher doses (1–2%) create sharper profiles. Proteases, often from microbial sources, accelerate protein breakdown, softening texture and intensifying umami in aged cheeses like Gruyère. However, overuse can lead to bitterness or excessive bitterness. Pairing enzymes with specific aging conditions—temperature, humidity, and duration—amplifies their effects. A 6-month aging period at 50–55°F (10–13°C) with controlled moisture allows enzymes to work optimally, balancing flavor development and texture.

The interplay of enzymes with milk composition further refines flavor. High-fat milks, like those used in cheddar, benefit from lipase activity, which creates complex, buttery notes. In contrast, low-fat cheeses rely more on proteolysis for flavor depth. For home cheesemakers, experimenting with enzyme types and dosages offers a playground for customization. Start with a baseline recipe, then adjust lipase or protease levels incrementally to observe changes. Documenting results over aging periods—3, 6, or 12 months—provides tangible insights into enzyme-driven transformations.

Finally, enzymes’ role in cheese flavor is not just scientific but artistic. They bridge the gap between raw ingredients and sensory experience, turning simplicity into sophistication. For instance, the same milk treated with different enzymes can yield a mild, creamy cheese or a bold, pungent one. This versatility underscores enzymes’ status as dairy’s most transformative tool. By mastering their use, cheesemakers—professional or amateur—can craft flavors that resonate with tradition or innovate boldly. The takeaway? Enzymes are not just dairy; they are the essence of cheese’s identity.

Caring for Your Wooden Cheese Board: Tips for Longevity and Beauty

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, cheese enzymes are typically derived from dairy sources, such as animal rennet from cows, goats, or sheep, making them dairy-based.

Yes, some cheese enzymes are non-dairy, such as microbial or plant-based rennet, which are used in vegetarian or vegan cheese production.

No, not all cheeses contain dairy-derived enzymes; many use non-dairy alternatives like microbial enzymes to coagulate milk.

It depends; dairy-derived enzymes may not be safe for those with dairy allergies, but non-dairy enzymes are generally safe for consumption.

Check the ingredient label; terms like "animal rennet" indicate dairy-based enzymes, while "microbial rennet" or "plant-based enzymes" suggest non-dairy sources.