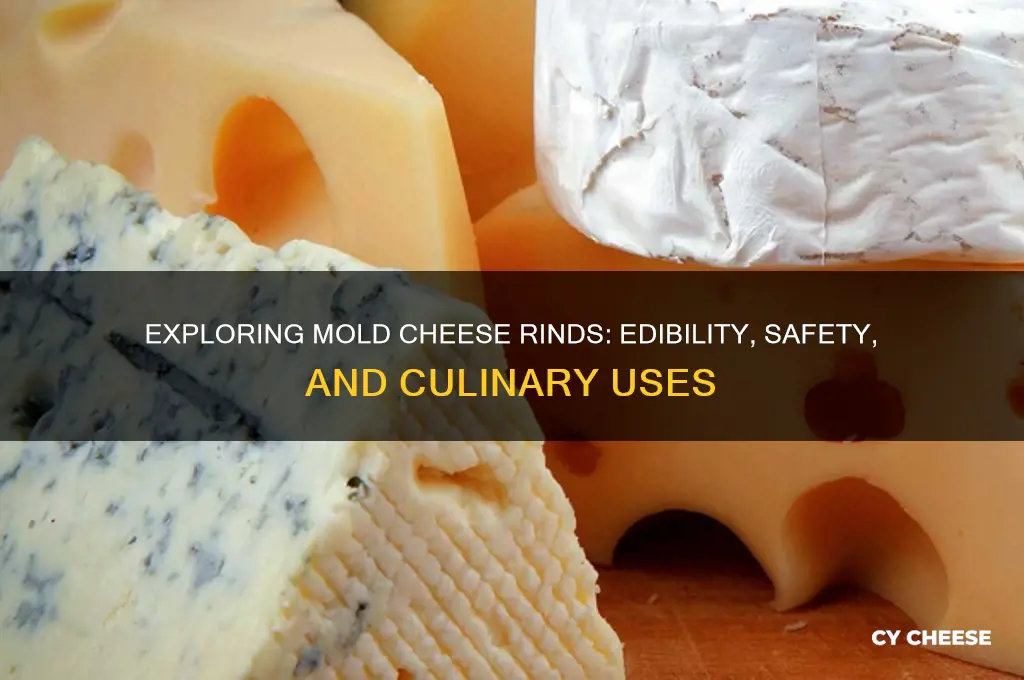

Mold cheese rinds are a fascinating and integral part of many artisanal cheeses, serving both functional and flavor-enhancing purposes. These rinds, often covered in a layer of mold, play a crucial role in the aging process by protecting the cheese from spoilage and contributing to its unique texture and taste. While some may find the appearance of mold off-putting, it is typically a sign of craftsmanship and tradition, as specific molds like Penicillium camemberti or Geotrichum candidum are intentionally cultivated to create signature cheeses such as Brie or Camembert. Understanding the role of mold in cheese rinds not only demystifies their presence but also highlights the artistry and science behind cheese-making.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Many mold cheese rinds are edible, especially those from cheeses like Brie, Camembert, and other soft-ripened cheeses. However, some rinds may be too tough or unpalatable. |

| Flavor | Rinds often contribute to the cheese's overall flavor, adding earthy, nutty, or mushroom-like notes. |

| Texture | Rinds can range from soft and velvety (e.g., Brie) to hard and waxy (e.g., Gouda) or even crusty (e.g., aged cheeses). |

| Mold Type | Common molds include Penicillium camemberti (Brie, Camembert) and Penicillium candidum (Chaource), which are safe for consumption. |

| Safety | Edible rinds are safe to eat, but non-edible rinds (e.g., wax or cloth-covered cheeses) should be removed. Always check the cheese type before consuming the rind. |

| Purpose | Rinds protect the cheese during aging, influence flavor development, and prevent excessive moisture loss. |

| Examples | Edible rinds: Brie, Camembert, Reblochon. Non-edible rinds: Parmesan, Cheddar (wax coating). |

| Health Concerns | Generally safe, but individuals with mold allergies or weakened immune systems should avoid consuming moldy rinds. |

| Storage Impact | Rinds help extend shelf life by protecting the cheese from external contaminants and controlling moisture. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Mold Cheese Rinds: Brief overview of common mold cheese rind varieties like Brie, Camembert, and others

- Edibility of Mold Cheese Rinds: Discussing whether mold cheese rinds are safe to eat or should be avoided

- Mold Cheese Rind Formation: Explaining how mold cheese rinds develop during the aging and ripening process

- Flavor Impact of Rinds: How mold cheese rinds contribute to the overall taste, texture, and aroma of the cheese

- Storing Mold Cheese with Rinds: Best practices for preserving and storing mold cheese to maintain rind integrity

Types of Mold Cheese Rinds: Brief overview of common mold cheese rind varieties like Brie, Camembert, and others

Mold-ripened cheeses are a testament to the delicate balance between microbial artistry and culinary tradition. Among these, Brie and Camembert stand as iconic examples, their velvety white rinds a canvas for *Penicillium camemberti*. This mold not only shields the cheese but also contributes to its signature earthy, nutty flavor. The rind is edible, though some prefer the creamy interior alone. For optimal enjoyment, serve these cheeses at room temperature to allow their textures and aromas to fully develop.

Beyond Brie and Camembert, blue-veined cheeses like Roquefort and Gorgonzola showcase a different mold—*Penicillium roqueforti*. Here, the rind plays a secondary role, as the mold penetrates the interior, creating distinctive veins. These cheeses are aged in specific conditions, such as the cool, damp caves of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, to encourage mold growth. Pair them with honey or walnuts to complement their pungent, tangy profiles.

Washed-rind cheeses, such as Époisses and Taleggio, introduce a third mold variety—*Brevibacterium linens*. This bacterium gives the rind a reddish-orange hue and a robust, barnyard aroma. The rind is typically thinner and more pungent than the interior, which remains creamy and mild. To appreciate these cheeses, let them breathe for 30 minutes before serving, and consider pairing them with crusty bread or a full-bodied red wine.

Finally, hard cheeses like Gruyère and Comté feature natural rinds formed during aging, often with mixed molds and yeasts. While less prominent than their soft counterparts, these rinds add complexity and protect the cheese during long maturation periods. Though edible, the rind’s texture can be tough, so many opt to pare it away. Use these cheeses in cooking to enhance dishes like fondue or quiche, where their flavors meld seamlessly.

Understanding these mold cheese rinds not only deepens appreciation but also guides proper storage and serving. Keep soft-ripened cheeses in the refrigerator but bring to room temperature before eating. Wrap washed-rind cheeses in wax paper to allow breathability, and store harder varieties in the coolest part of the fridge. Each rind tells a story of craftsmanship and science, making mold-ripened cheeses a cornerstone of the cheesemaker’s art.

Elevate Your Mac and Cheese: Creative Flavor-Boosting Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Edibility of Mold Cheese Rinds: Discussing whether mold cheese rinds are safe to eat or should be avoided

Mold-ripened cheeses, such as Brie, Camembert, and blue cheese, boast a distinctive rind that often sparks debate: is it safe to eat? The answer lies in understanding the type of mold and the cheese-making process. Unlike harmful molds that grow on spoiled food, the molds in these cheeses are intentionally cultivated to enhance flavor and texture. For instance, *Penicillium camemberti* in Brie and *Penicillium roqueforti* in blue cheese are not only safe but integral to the cheese’s character. However, not all moldy cheeses are created equal—unintended mold growth on aged cheeses like cheddar or gouda is a red flag and should be discarded.

Analyzing the Risks and Benefits

Eating the rind of mold-ripened cheeses is generally safe for most people, but exceptions exist. Individuals with mold allergies, compromised immune systems, or respiratory conditions like asthma should avoid consuming these rinds, as they may trigger adverse reactions. Pregnant women are also advised to exercise caution due to potential risks associated with certain molds. For the average consumer, the rind contributes to the cheese’s complexity, offering earthy, nutty, or mushroom-like flavors. However, if the rind appears excessively thick, discolored, or has an off-putting odor, it’s best to trim it off or avoid the cheese altogether.

Practical Tips for Consumption

When enjoying mold-ripened cheeses, consider the following guidelines. First, inspect the cheese for signs of spoilage, such as an ammonia-like smell or slimy texture, which indicate it’s past its prime. Second, if you’re unsure about the rind’s edibility, consult the packaging or the cheesemonger for guidance. For softer cheeses like Brie, the thin, bloomy rind is typically edible and enhances the experience when paired with crackers or bread. Harder cheeses with natural rinds, like Gruyère, often have rinds that are too tough to eat but can be used to flavor soups or stews.

Comparing Edible and Non-Edible Rinds

Not all cheese rinds are meant to be eaten. Wax coatings on cheeses like Gouda or Edam are purely protective and should be removed before consumption. Similarly, cloth-bound cheeses like Cheddar have rinds that are too dry and flavorless to enjoy. In contrast, washed-rind cheeses like Époisses or Taleggio have edible rinds, though their strong aroma and sticky texture may not appeal to everyone. Understanding the type of rind and its purpose allows you to make informed decisions about whether to eat it or trim it away.

For most healthy individuals, the rind of mold-ripened cheeses is not only safe but a delightful part of the culinary experience. It encapsulates the artistry of cheese-making, offering a depth of flavor that the interior alone cannot provide. However, always prioritize safety by checking for spoilage and considering personal health conditions. When in doubt, err on the side of caution and remove the rind. By doing so, you can savor these cheeses confidently, appreciating both their interior creaminess and the nuanced flavors of their carefully crafted exteriors.

Why Cats Gag at Cheese Smell: Unraveling the Feline Mystery

You may want to see also

Mold Cheese Rind Formation: Explaining how mold cheese rinds develop during the aging and ripening process

Mold cheese rinds are not accidental; they are the result of a deliberate and fascinating interplay between microorganisms, humidity, and time. During the aging and ripening process, cheese is exposed to specific molds, either naturally present in the environment or introduced intentionally. These molds, such as *Penicillium camemberti* in Camembert or *Penicillium roqueforti* in blue cheese, colonize the cheese surface, forming a rind that protects the interior while contributing to flavor and texture development. The rind acts as a barrier, regulating moisture loss and oxygen exposure, which are critical for the cheese’s transformation.

The formation of a mold cheese rind begins with the cheese’s surface conditions. After curds are pressed and salted, the cheese is placed in a controlled environment with specific temperature (typically 50–55°F or 10–13°C) and humidity (around 90–95%) levels. These conditions encourage mold spores to germinate and grow. For example, in Brie production, the cheese is inoculated with *Penicillium camemberti* spores, which thrive in these conditions, forming a velvety white rind within 7–10 days. The mold’s mycelium (thread-like structures) gradually covers the cheese, breaking down proteins and fats, which contributes to the cheese’s characteristic aroma and taste.

Not all mold rinds are created equal; their appearance and texture depend on the cheese variety and aging techniques. Natural rinds develop when molds grow spontaneously in the aging room, as seen in traditional farmhouse cheeses. In contrast, washed-rind cheeses like Époisses are periodically brushed with brine or alcohol solutions, fostering the growth of bacteria (*Brevibacterium linens*) alongside molds, resulting in a sticky, orange-hued rind. Blue cheeses are pierced to allow oxygen penetration, encouraging mold growth internally as well as externally. Each method highlights how human intervention and microbial activity collaborate to shape the rind’s character.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers include maintaining consistent humidity and temperature during aging, as fluctuations can disrupt mold growth. For washed-rind cheeses, use a 10–15% saltwater solution to encourage bacterial activity without overwhelming the mold. Avoid touching the rind excessively, as oils from hands can inhibit mold development. If unwanted molds appear (e.g., green or black spots), trim them carefully, ensuring the cheese is still safe to consume. Understanding these processes empowers both makers and enthusiasts to appreciate the artistry behind mold cheese rinds.

Unveiling Cheese Walker's Dominant Strain: A Genetic Exploration

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Flavor Impact of Rinds: How mold cheese rinds contribute to the overall taste, texture, and aroma of the cheese

Mold-ripened cheeses, such as Brie, Camembert, and blue cheeses, owe much of their complexity to the rinds that encase them. These rinds are not mere protective barriers; they are active participants in the cheese's flavor development. The mold cultures on the rind—often Penicillium camemberti or Penicillium roqueforti—break down the cheese's proteins and fats, releasing compounds that contribute to its distinctive taste, aroma, and texture. This process, known as proteolysis and lipolysis, transforms the cheese from a simple curd into a nuanced, multi-sensory experience.

Consider the texture: the rind of a soft-ripened cheese like Brie is thin and bloomy, creating a contrast between the creamy interior and the slightly firmer, earthy exterior. This textural duality enhances the eating experience, inviting you to savor the interplay between smoothness and subtle resistance. In harder cheeses, such as aged Gouda, the rind becomes drier and more robust, adding a satisfying chewiness that complements the crystalline interior. The rind’s texture is not just a byproduct of aging; it is a deliberate outcome of mold activity, which influences moisture loss and surface hardening over time.

Aroma is another critical dimension shaped by the rind. As molds metabolize the cheese, they produce volatile compounds like methyl ketones and esters, which contribute to the cheese's bouquet. For instance, the white rind of Camembert emits a pungent, mushroom-like scent, while the blue veins in Roquefort release sharp, spicy notes. These aromas are not confined to the rind; they permeate the cheese, creating a cohesive olfactory profile. To maximize aroma appreciation, let the cheese sit at room temperature for 30–60 minutes before serving, allowing the volatile compounds to fully express themselves.

Taste is perhaps the most direct way the rind influences the cheese. The mold cultures on the rind introduce umami, earthy, and nutty flavors that deepen the cheese's overall profile. In washed-rind cheeses like Époisses, bacteria on the rind produce ammonia compounds, lending a bold, tangy flavor that balances the richness of the interior. For optimal flavor integration, pair mold-ripened cheeses with beverages that complement their rind-derived characteristics—for example, a crisp white wine with Brie or a robust porter with blue cheese.

Practical tip: when serving mold-ripened cheeses, consider whether to include the rind. While the rind is safe to eat and contributes significantly to flavor, some palates may find it too intense. For soft cheeses, encourage guests to taste a bite with and without the rind to compare. For harder cheeses, shave the rind into thin pieces to make it more palatable. Ultimately, the rind is not just a wrapper—it’s a flavor powerhouse that elevates the cheese from ordinary to extraordinary.

Did the Cheese Touch Start in Wimpy Kid? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Storing Mold Cheese with Rinds: Best practices for preserving and storing mold cheese to maintain rind integrity

Mold-ripened cheeses, such as Brie, Camembert, and aged Goudas, owe much of their complex flavors and textures to their rinds. Proper storage is critical to preserving the integrity of these rinds, ensuring the cheese continues to develop optimally without spoiling. The key lies in balancing humidity, temperature, and airflow to mimic the conditions of a cheese cave. Wrap the cheese in wax or parchment paper, followed by a loose layer of aluminum foil, to allow the rind to breathe while preventing excessive moisture loss. Avoid plastic wrap, as it traps moisture and encourages undesirable mold growth.

Temperature control is paramount for mold cheese with rinds. Store these cheeses in the warmest part of your refrigerator, ideally at 45–50°F (7–10°C). This range slows bacterial activity while allowing the cheese to mature gradually. For softer cheeses like Brie, monitor the rind weekly for signs of over-ripening, such as excessive ammonia aromas or a slimy texture. If the cheese feels too soft, move it to a slightly cooler area of the fridge to slow the aging process.

Humidity management is equally crucial for rind preservation. Most refrigerators are too dry for mold-ripened cheeses, causing the rind to crack or harden. To combat this, place the wrapped cheese in a lidded container with a damp (not wet) paper towel. This creates a microenvironment with 80–90% humidity, ideal for maintaining rind elasticity and preventing dehydration. Check the towel every few days, rewetting it as needed to sustain consistent moisture levels.

Rotation and inspection are often overlooked but essential practices. Turn the cheese weekly to ensure even aging and prevent the rind from sticking to the wrapping. Inspect for off-odors, discoloration, or unusual mold growth, which may indicate improper storage conditions. For long-term storage (beyond 4 weeks), consider using a cheese storage bag with a breathable membrane, designed to regulate moisture and protect the rind from mechanical damage.

Finally, when ready to consume, allow the cheese to come to room temperature for at least an hour. This softens the rind and enhances flavor expression. If the rind has developed a thick, waxy layer (common in aged cheeses like Gruyère), trim it slightly to reveal the paste beneath. Properly stored, mold cheese with rinds can age gracefully, rewarding you with a symphony of flavors and textures that reflect the artistry of its creation.

Are Cheese Balls Fried? Uncovering the Truth Behind This Snack

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mold cheese rind is the outer layer of certain cheeses that develops mold during the aging process, often intentionally introduced to enhance flavor and texture.

Generally, yes, it is safe to eat mold cheese rind on cheeses like Brie, Camembert, or Blue Cheese, as the mold is part of the cheese-making process. However, if the cheese is not meant to have mold or shows signs of spoilage, avoid consuming the rind.

Yes, you can remove the mold cheese rind if you prefer, especially if you’re unsure about its safety or simply don’t like the texture or flavor. The interior of the cheese is usually safe to eat.

Cheeses with edible mold rinds include Brie, Camembert, Blue Cheese, and some washed-rind cheeses like Époisses. These molds are part of the cheese's character and are safe to consume.

Safe mold on cheese rind is typically uniform in color (e.g., white, blue, or gray) and is part of the cheese's intended aging process. Harmful mold appears irregular, colorful (e.g., green, black, or pink), and is often found on cheeses not meant to have mold, indicating spoilage.