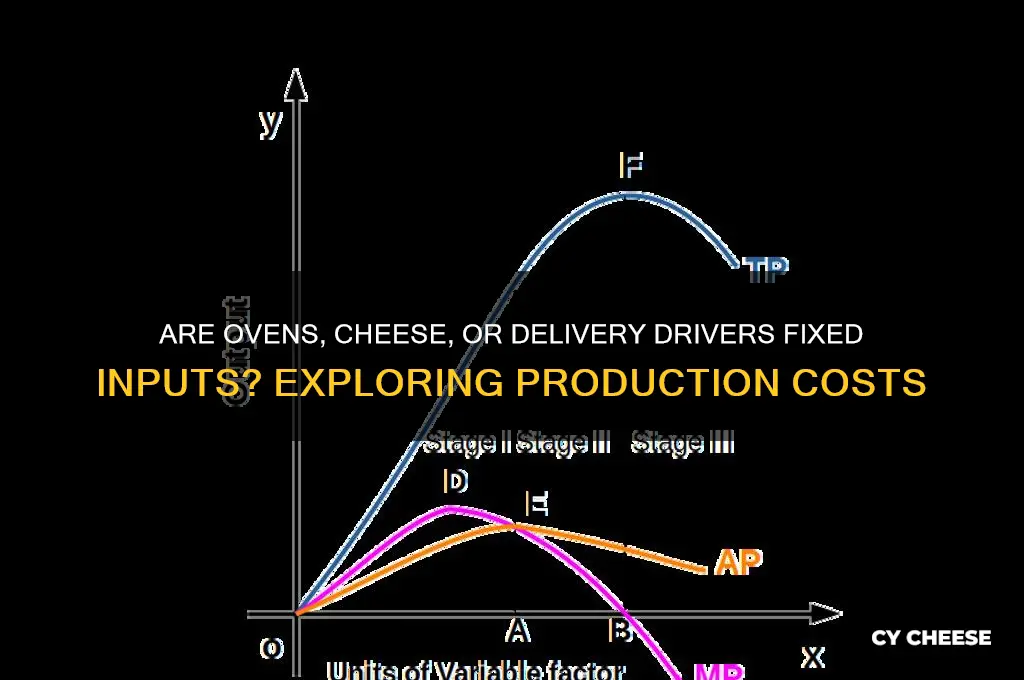

The question of whether ovens, cheese, or delivery drivers are considered fixed inputs can be quite perplexing, as these elements belong to distinct categories in various contexts. In economics and production theory, fixed inputs refer to resources that remain constant in the short term, regardless of the output level. Ovens, for instance, could be seen as fixed inputs in a bakery, as their quantity doesn't change with the number of baked goods produced. Cheese, on the other hand, is typically a variable input in food production, as its usage depends on the specific recipe or demand. Delivery drivers, in the context of logistics, might be considered semi-fixed, as their availability can be adjusted, but their role remains crucial for distributing goods. Understanding the nature of these inputs is essential for optimizing production processes and resource allocation in different industries.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Oven Functionality: Are ovens considered fixed inputs in production processes or variable assets

- Cheese Production: Is cheese a fixed input in food manufacturing or a variable cost

- Delivery Drivers Role: Are delivery drivers fixed inputs in logistics or flexible resources

- Cost Classification: How are ovens, cheese, and drivers categorized in cost accounting

- Operational Efficiency: Do ovens, cheese, or drivers impact fixed input optimization strategies

Oven Functionality: Are ovens considered fixed inputs in production processes or variable assets?

Ovens, as essential components in various production processes, raise questions about their classification as fixed inputs or variable assets. In economic terms, fixed inputs are resources that remain constant in the short term, regardless of the level of output, while variable inputs change with production levels. To determine where ovens fit, consider their role in industries like baking, manufacturing, or food processing. For instance, in a bakery, the oven’s capacity is fixed; it can only handle a certain number of loaves per batch, regardless of demand. This suggests ovens behave as fixed inputs, as their output is constrained by physical limitations rather than scalability.

However, the classification isn’t always clear-cut. In some settings, ovens can be adjusted or upgraded to increase capacity, blurring the line between fixed and variable. For example, modular ovens in industrial settings allow for additional units to be added as production needs grow. This adaptability introduces a variable element, as the input (oven capacity) can change over time. Yet, even in these cases, the core oven infrastructure remains a fixed cost, requiring significant investment to alter. Thus, while flexibility exists, ovens primarily align with fixed inputs due to their upfront capital intensity and limited short-term adjustability.

From a practical standpoint, treating ovens as fixed inputs has implications for cost management and production planning. Businesses must account for the oven’s fixed costs, such as depreciation and maintenance, regardless of output levels. This necessitates strategies like maximizing utilization during peak hours or diversifying product lines to ensure consistent oven use. For instance, a pizzeria might offer breadsticks or desserts during slower periods to optimize oven efficiency. Recognizing ovens as fixed inputs also guides decisions on scaling—expanding production often requires additional ovens, a substantial investment compared to variable inputs like raw materials.

Comparatively, ovens differ from inputs like delivery drivers or cheese, which are inherently variable. Delivery drivers can adjust their hours or routes based on demand, and cheese is purchased in quantities directly tied to production needs. Ovens, however, lack this immediate flexibility. While their usage can be optimized, their physical presence and capacity remain constant in the short term. This distinction underscores why ovens are typically categorized as fixed inputs, despite occasional exceptions in highly adaptable systems.

In conclusion, ovens are best considered fixed inputs in most production processes due to their physical constraints and upfront costs. While advancements like modular designs introduce some variability, the core infrastructure remains constant. Understanding this classification helps businesses manage costs, plan production, and make informed decisions about scaling. By treating ovens as fixed inputs, companies can focus on optimizing their use and balancing other variable resources to achieve efficiency and growth.

Does Wax-Wrapped Cheese Require Refrigeration? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Cheese Production: Is cheese a fixed input in food manufacturing or a variable cost?

Cheese, a staple in food manufacturing, often blurs the line between fixed input and variable cost. To determine its classification, consider the scale and nature of production. In small-scale operations, cheese might be purchased in fixed quantities weekly, resembling a fixed input. However, for large-scale manufacturers, cheese consumption fluctuates with production volume, aligning it more closely with variable costs. This duality hinges on whether cheese is a core ingredient or an optional additive in the product line.

Analyzing cheese as a fixed input reveals its limitations. Fixed inputs remain constant regardless of output, but cheese usage rarely fits this mold. For instance, a pizzeria might order a consistent amount of mozzarella weekly, but this quantity adjusts during peak seasons or promotions. Thus, while cheese may appear fixed in short-term planning, it adapts to demand, undermining its fixed-input status. This adaptability is a hallmark of variable costs, not fixed ones.

From a persuasive standpoint, treating cheese as a variable cost offers strategic advantages. Variable costs scale with production, allowing businesses to optimize spending during slow periods. For example, a cheese-based snack manufacturer can reduce cheese orders when sales dip, minimizing waste and preserving cash flow. This flexibility is crucial in volatile markets, where fixed costs can become liabilities. Viewing cheese as variable empowers businesses to respond dynamically to market shifts.

Comparatively, industries like baking often treat flour as a variable cost, despite its consistent use. Similarly, cheese should be categorized based on its role in production. In cheese-centric products like macaroni and cheese, it’s a primary variable cost. In contrast, for products where cheese is a minor component, it might be grouped with fixed overheads. This distinction requires businesses to assess cheese’s proportional impact on total costs and production volume.

Practically, businesses can implement cost-tracking systems to monitor cheese usage. For instance, a dairy processor might use software to correlate cheese purchases with production batches, identifying trends. This data-driven approach clarifies whether cheese behaves as a fixed or variable input in their specific context. Additionally, negotiating bulk discounts for cheese can mitigate variable cost impacts, blending fixed-cost benefits into a variable framework. Such strategies ensure cheese remains a manageable expense, regardless of classification.

Where to Find the Classic Steak, Egg, and Cheese Bagel in the U.S

You may want to see also

Delivery Drivers Role: Are delivery drivers fixed inputs in logistics or flexible resources?

In logistics, the classification of delivery drivers as fixed inputs or flexible resources hinges on operational context and strategic priorities. Fixed inputs are typically unchanging elements essential for production, like machinery, while flexible resources adapt to demand fluctuations. Delivery drivers, however, occupy a gray area. For instance, a small pizzeria with a dedicated driver operates with a fixed input model, as the driver’s role is constant regardless of order volume. Conversely, a large e-commerce platform like Amazon relies on a flexible pool of drivers, scaling up or down based on seasonal demand. This duality underscores the need to assess drivers’ roles within specific logistical frameworks.

Consider the analytical perspective: delivery drivers’ flexibility is often tied to employment models. Full-time, salaried drivers function as fixed inputs, providing consistent capacity but limiting scalability. Gig economy workers, on the other hand, offer elasticity, allowing companies to match supply with real-time demand. For example, Uber Eats leverages independent contractors to handle peak hours without overstaffing during lulls. This model reduces fixed costs but introduces variability in service quality and driver availability. Thus, the choice between fixed and flexible depends on balancing cost efficiency with operational reliability.

From a practical standpoint, treating delivery drivers as flexible resources requires robust management systems. Companies must invest in technology to optimize driver allocation, such as route optimization software or real-time tracking tools. For instance, DHL’s dynamic routing algorithms adjust delivery schedules based on traffic and order volume, maximizing driver utilization. However, this approach demands significant upfront investment and ongoing maintenance. Small businesses may find the fixed input model more feasible, despite its limitations, due to lower complexity and predictable costs.

A comparative analysis reveals that the fixed input model excels in scenarios requiring consistent service quality and brand control. High-end retailers like Nordstrom use in-house drivers to ensure premium delivery experiences, aligning with their luxury positioning. In contrast, flexible resources suit businesses prioritizing scalability and cost control. Meal kit services like HelloFresh, which experience weekly demand spikes, rely on third-party drivers to manage fluctuations without overburdening core operations. Each model’s effectiveness depends on aligning driver classification with business objectives.

Ultimately, delivery drivers are neither inherently fixed inputs nor universally flexible resources. Their classification depends on operational needs, employment structures, and technological capabilities. Companies must evaluate their logistical ecosystems to determine the optimal approach. For instance, a hybrid model—combining a core fixed team with on-demand flexible drivers—can offer stability and adaptability. By strategically categorizing drivers, businesses can enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and improve customer satisfaction in an increasingly competitive logistics landscape.

Can Dogs Eat Cheese? Safety, Benefits, and Risks Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cost Classification: How are ovens, cheese, and drivers categorized in cost accounting?

In cost accounting, the classification of costs is crucial for decision-making, budgeting, and financial analysis. Ovens, cheese, and delivery drivers each fall into distinct cost categories based on their behavior and function within a business. Understanding these classifications helps businesses manage resources efficiently and optimize profitability.

Ovens are typically classified as fixed costs in the short term. Fixed costs remain constant regardless of production volume. For a bakery or restaurant, an oven’s cost—whether through purchase, lease, or depreciation—does not change with the number of items baked. However, over the long term, ovens may require maintenance or replacement, which could introduce variable elements. For instance, a commercial oven costing $10,000 with a 10-year lifespan would depreciate at $1,000 annually, a fixed expense. Yet, unexpected repairs could add variability, though these are often budgeted as contingencies.

Cheese, in contrast, is a variable cost for businesses like pizzerias or cheesemakers. Variable costs fluctuate directly with production or sales volume. If a pizzeria uses 2 pounds of cheese per pizza and sells 100 pizzas daily, it would require 200 pounds of cheese, costing approximately $500 (assuming $2.50 per pound). If sales double, cheese costs double too. This direct proportionality makes cheese a classic example of a variable cost. However, bulk purchasing or price fluctuations could slightly alter this relationship, though the core variability remains.

Delivery drivers present a more nuanced classification, often falling into the semi-variable cost category. Semi-variable costs have both fixed and variable components. A delivery driver’s salary might include a fixed base pay (e.g., $500 weekly) plus a variable component tied to deliveries (e.g., $5 per delivery). If the driver makes 50 deliveries weekly, the total cost would be $750. While the base pay remains fixed, the variable portion scales with activity. Additionally, vehicle maintenance and fuel costs add further variability, making drivers a hybrid cost that requires careful tracking and allocation.

In practice, businesses must analyze these classifications to allocate budgets effectively. For example, a restaurant might prioritize reducing variable costs like cheese by negotiating supplier contracts or minimizing waste. Conversely, fixed costs like ovens could be optimized through energy-efficient models or leasing instead of purchasing. For semi-variable costs like drivers, route optimization software or performance incentives could balance fixed and variable elements. By understanding these distinctions, businesses can enhance cost control and improve financial performance.

Does In-N-Out Secretly Serve Chili Cheese Fries? Find Out!

You may want to see also

Operational Efficiency: Do ovens, cheese, or drivers impact fixed input optimization strategies?

Ovens, cheese, and delivery drivers each play distinct roles in operational efficiency, but their impact on fixed input optimization strategies varies significantly. Ovens, as capital equipment, are typically considered fixed inputs because their capacity and cost remain constant over a production period. For instance, a bakery’s oven operates within a set capacity, and its efficiency hinges on maximizing output without overloading it. Cheese, on the other hand, is a variable input in most food production scenarios. Its usage fluctuates based on demand, and optimizing its cost involves inventory management and waste reduction. Delivery drivers, while essential, are semi-fixed inputs; their efficiency depends on route optimization, workload balancing, and vehicle utilization. Understanding these classifications is crucial for tailoring strategies to each input type.

To optimize fixed inputs like ovens, focus on utilization rates and maintenance schedules. For example, a pizzeria can increase oven efficiency by batching orders during peak hours and scheduling preventive maintenance during off-peak times. This reduces downtime and ensures consistent output. Variable inputs like cheese require dynamic strategies, such as just-in-time inventory systems to minimize spoilage. A dairy supplier might offer bulk discounts, but purchasing more than needed could lead to waste. For semi-fixed inputs like delivery drivers, technology-driven solutions such as GPS routing and real-time tracking can significantly enhance productivity. A case study of a food delivery company showed a 20% reduction in delivery times after implementing route optimization software.

Persuasively, businesses must recognize that treating all inputs as interchangeable undermines efficiency. For instance, allocating budget cuts to oven maintenance to save costs may seem prudent but could lead to costly breakdowns. Similarly, over-relying on drivers without optimizing routes wastes labor and fuel. Cheese, often overlooked, can be a leverage point for cost savings through supplier negotiations or alternative sourcing. A comparative analysis reveals that fixed inputs benefit most from capacity planning, variable inputs from demand forecasting, and semi-fixed inputs from process automation.

Descriptively, imagine a small-scale cheese manufacturer with a single oven and a fleet of drivers. The oven’s fixed capacity limits daily production, so the manufacturer must prioritize high-margin products during peak hours. Cheese inventory is managed through weekly orders based on sales forecasts, reducing excess stock. Drivers are assigned routes using algorithms that account for traffic and delivery windows, ensuring timely service. This holistic approach demonstrates how aligning strategies with input types enhances overall efficiency.

Instructively, to implement these strategies, start by categorizing inputs in your operation. For fixed inputs like ovens, invest in training staff to operate equipment at peak efficiency and monitor performance metrics. For variable inputs like cheese, establish partnerships with reliable suppliers and implement inventory tracking systems. For semi-fixed inputs like drivers, adopt technology tools to streamline logistics and monitor driver performance. Regularly review and adjust strategies based on data insights to ensure continuous improvement. By treating each input uniquely, businesses can unlock significant operational efficiencies.

Crawford's Cheese Savouries: Are They Vegetarian-Friendly?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, ovens are typically considered fixed inputs in production because they are capital goods that cannot be easily or quickly changed in the short term.

No, delivery drivers are generally not considered fixed inputs. They are variable inputs because their number can be adjusted based on demand or production needs.

No, cheese is not a fixed input. It is a variable input because the quantity used can be adjusted depending on the scale of production or specific recipes.