When exploring the diverse world of cheese, one might wonder if there are any traditional Asian cheeses. Unlike the well-known European varieties, Asian cheeses are less prominent globally but hold a unique place in regional cuisines. Countries like China, Japan, India, and Mongolia have their own cheese traditions, often deeply rooted in local culture and history. From the mildly sour Chinese *Rubing* to the stretchy Japanese *Sakurambo* and the creamy Indian *Paneer*, these cheeses showcase the ingenuity of Asian dairy craftsmanship. While they may not dominate international markets, Asian cheeses offer a fascinating glimpse into the continent's culinary diversity and the ways dairy has been adapted to local tastes and techniques.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Existence of Asian Cheeses | Yes, there are several traditional Asian cheeses. |

| Examples | Chhurpi (Nepal/Tibet), Rubing (China), Kesong Puti (Philippines), Byambi (Mongolia), Ruou (Vietnam), etc. |

| Texture | Ranges from soft and creamy (Kesong Puti) to hard and chewy (Chhurpi). |

| Flavor Profile | Mild, tangy, salty, or smoky, depending on the type and production method. |

| Milk Source | Primarily cow, yak, buffalo, or goat milk. |

| Production Method | Often involves simple curdling with acid (vinegar, lemon juice) or rennet. |

| Aging | Some are consumed fresh, while others are aged for weeks or months. |

| Cultural Significance | Integral to local cuisines and traditions, often used in cooking or as snacks. |

| Popularity | Less globally known compared to European cheeses but gaining recognition. |

| Availability | Mostly found in local markets or specialty stores in Asia, with limited export. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Traditional Asian Cheese Varieties: Explore cheeses like Chinese Rubing, Korean Imsil, and Indian Paneer

- Cheese Production Techniques: Discover unique methods used in Asia for cheese-making, often differing from Western practices

- Cultural Significance of Cheese: Understand cheese’s role in Asian cuisines, traditions, and historical contexts

- Modern Asian Cheese Innovations: Highlight contemporary cheeses blending Asian flavors with global cheese-making techniques

- Regional Cheese Specialties: Focus on specific Asian regions known for their distinct cheese varieties and recipes

Traditional Asian Cheese Varieties: Explore cheeses like Chinese Rubing, Korean Imsil, and Indian Paneer

Asian cheeses, though less globally recognized than their European counterparts, offer a rich tapestry of flavors, textures, and cultural significance. Among these, Chinese Rubing, Korean Imsil, and Indian Paneer stand out as distinct varieties that reflect the ingenuity of traditional cheese-making practices in Asia. Each of these cheeses is deeply rooted in its region’s culinary heritage, yet they share a common thread: simplicity in ingredients and a focus on versatility in cooking.

Chinese Rubing, often referred to as "milk skin cheese," is a prime example of resourcefulness in cheese-making. Made by simmering milk until a skin forms on the surface, this skin is then collected, layered, and pressed into a firm, creamy cheese. Rubing’s mild, slightly nutty flavor makes it a perfect pairing for both savory and sweet dishes. Traditionally, it is served with honey or incorporated into stir-fries, adding a rich, velvety texture. To make Rubing at home, simmer 1 liter of milk over low heat for 30–40 minutes, gently lifting the skin as it forms, and layering it until you achieve the desired thickness.

In contrast, Korean Imsil is a fermented cheese with a tangy, slightly sour profile, reminiscent of cottage cheese but with a firmer texture. Made from cow’s or goat’s milk, Imsil is often aged in traditional earthenware pots, which impart a unique earthy flavor. This cheese is a staple in Korean cuisine, used in dishes like *dubuseon* (stuffed cucumber kimchi) or simply enjoyed with rice wine. Its fermentation process not only enhances its flavor but also increases its shelf life, making it a practical choice for preservation. For those interested in experimenting, start by heating milk to 37°C (98.6°F), adding a starter culture, and allowing it to ferment for 24–48 hours before draining and pressing.

Indian Paneer, perhaps the most widely recognized Asian cheese, is a fresh, unsalted cheese made by curdling milk with an acid like lemon juice or vinegar. Its crumbly yet smooth texture and neutral taste make it a versatile ingredient in Indian cooking, starring in dishes like palak paneer and mattar paneer. Unlike Rubing and Imsil, Paneer does not melt, making it ideal for frying or grilling. To prepare Paneer at home, heat 1 liter of whole milk to 80°C (176°F), add 2 tablespoons of lemon juice, and stir until curds form. Strain the curds through a cheesecloth, press out excess liquid, and let it set under a heavy weight for 1–2 hours.

While these cheeses differ in production methods and flavor profiles, they collectively challenge the notion that Asia lacks a cheese tradition. Rubing’s simplicity, Imsil’s fermentation, and Paneer’s adaptability showcase the diversity of Asian cheese-making. Incorporating these cheeses into your culinary repertoire not only broadens your palate but also connects you to centuries-old traditions. Whether you’re simmering milk for Rubing, fermenting Imsil in an earthen pot, or pressing Paneer for a curry, each process offers a hands-on way to explore Asia’s rich dairy heritage.

Cheese and Onion Fry It: A Crispy, Cheesy Snack Explained

You may want to see also

Cheese Production Techniques: Discover unique methods used in Asia for cheese-making, often differing from Western practices

Asia's cheese landscape challenges the notion that cheese is solely a Western delicacy. From the creamy, yogurt-like byaslag of Mongolia to the stretchy, mozzarella-esque chhurpi of Nepal, Asian cheeses showcase a distinct identity shaped by local ingredients, climates, and traditions. Unlike their European counterparts, many Asian cheeses rely on non-bovine milk sources like yak, buffalo, and even camel, reflecting the region's diverse livestock. This fundamental difference in milk composition necessitates unique production techniques, setting Asian cheese-making apart from Western practices.

One striking example is the use of natural fermentation instead of rennet in many Asian cheeses. Traditional Mongolian byaslag, for instance, is made by simply boiling milk and allowing it to curdle naturally with the help of lactic acid bacteria present in the environment. This method, while slower, imparts a distinct tangy flavor and a softer texture compared to rennet-coagulated cheeses. Similarly, India's paneer relies on the addition of lemon juice or vinegar to curdle milk, a technique that yields a crumbly, fresh cheese ideal for absorbing spices in curries.

Another unique aspect is the utilization of traditional tools and vessels. In Tibet, chhurpi is often made in large copper pots called thukpa, which conduct heat evenly and contribute to the cheese's characteristic smoky flavor. In the Philippines, kesong puti is traditionally wrapped in banana leaves, imparting a subtle earthy aroma and aiding in moisture retention during the draining process. These tools are not merely functional; they are integral to the cultural identity and flavor profile of these cheeses.

Unlike the aging process common in Western cheeses, many Asian varieties are consumed fresh or undergo minimal aging. This is partly due to climatic conditions, as high temperatures can accelerate spoilage. However, some exceptions exist, like China's Rubing, a hard, aged cheese made from yak milk. Rubing is often buried in pits lined with pine needles, allowing it to develop a complex, nutty flavor over several months. This technique showcases the ingenuity of Asian cheese-makers in adapting to their environment and creating unique flavor profiles.

Exploring Asian cheese-making techniques offers a fascinating glimpse into the diversity of global culinary traditions. By embracing natural fermentation, utilizing traditional tools, and adapting to local conditions, Asian cheese-makers have developed a distinct and delicious array of cheeses that deserve recognition and appreciation on the world stage.

Mastering the Art of Beer and Cheese Pairing: A Tasting Guide

You may want to see also

Cultural Significance of Cheese: Understand cheese’s role in Asian cuisines, traditions, and historical contexts

Cheese, often associated with European culinary traditions, has a lesser-known but equally fascinating role in Asian cultures. While not as ubiquitous as in Western diets, Asian cheeses offer a unique lens into regional flavors, techniques, and historical exchanges. From the stretchy *ruan qian* of China to the pungent *chhurpi* of the Himalayas, these cheeses reflect local ingredients, climates, and culinary ingenuity. Their existence challenges the notion that cheese is exclusively a Western creation, revealing a global tapestry of dairy craftsmanship.

Consider the historical context of cheese in Asia, where dairy consumption was not always widespread due to lactose intolerance and agricultural practices. Yet, in regions like Mongolia and Tibet, where pastoralism thrived, milk preservation through fermentation and curdling became essential. *Byaslag*, a Mongolian cheese made from mare’s milk, exemplifies this adaptation. Its production aligns with nomadic lifestyles, providing a portable, nutrient-dense food source. Such cheeses are not just culinary items but symbols of survival, resilience, and cultural identity in harsh environments.

In South and Southeast Asia, cheese often takes on a sweeter, more dessert-oriented role. India’s *paneer* and Bangladesh’s *chhana* are fresh, unsalted cheeses used in both savory and sweet dishes. Their mild flavor and crumbly texture make them versatile ingredients in curries, sweets, and snacks. Unlike aged European cheeses, these varieties are typically consumed fresh, reflecting a preference for subtlety and balance in Asian cuisines. Their preparation methods, often involving simple curdling with lemon juice or vinegar, highlight accessibility and practicality in home cooking.

The cultural significance of Asian cheeses extends beyond their culinary uses. In Nepal, *chhurpi* is more than a food—it’s a social and economic cornerstone for mountain communities. Made from buttermilk, this hard cheese is traded, gifted, and shared during festivals, reinforcing communal bonds. Similarly, in Japan, *sakurayu* (cherry blossom cheese) is a seasonal delicacy, blending dairy with local aesthetics to celebrate spring. These examples illustrate how cheese becomes a medium for cultural expression, connecting people to their heritage, environment, and each other.

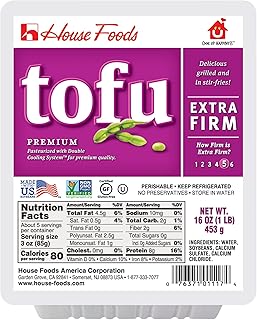

To explore Asian cheeses is to uncover a world of diversity and innovation. For those interested in experimenting, start with accessible varieties like *paneer* or *tofu* (often used as a cheese substitute in East Asian cooking). Pair *chhurpi* with local teas to appreciate its bold flavor, or incorporate *ruan qian* into stir-fries for a stretchy, savory twist. By embracing these cheeses, we not only expand our palates but also honor the traditions and histories they represent. In doing so, we challenge Eurocentric narratives and celebrate the global legacy of cheese.

Mastering the Art of Smoking Cheese with Cheesecloth Techniques

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Modern Asian Cheese Innovations: Highlight contemporary cheeses blending Asian flavors with global cheese-making techniques

Asian cheeses, often overshadowed by their European counterparts, are experiencing a renaissance as modern cheesemakers blend traditional Asian flavors with global techniques. This fusion is not just a trend but a culinary evolution, creating cheeses that are both familiar and groundbreaking. For instance, yuzu-infused cheddars and miso-aged bries are now gracing artisanal cheese boards, offering a unique twist to classic varieties. These innovations cater to a growing appetite for cross-cultural culinary experiences, proving that cheese knows no borders.

To create such cheeses, cheesemakers start with traditional bases like cheddar, gouda, or brie, then incorporate Asian ingredients during aging or as coatings. For example, matcha-dusted camembert combines the earthy flavor of green tea with the creamy richness of French cheese, while sichuan peppercorn-infused gouda adds a numbing spice that lingers on the palate. The key lies in balancing flavors—too much yuzu can overpower, while a subtle miso glaze enhances umami without dominating. Experimentation is crucial; pairing ingredients like kimchi brine with feta requires precise timing to avoid sourness.

One standout example is tofu-based cheeses, a vegan innovation that leverages Asian fermentation techniques. By culturing soy milk with kojic acid and aging it with shiitake mushrooms, cheesemakers create a product that mimics the texture of soft cheese while embracing plant-based diets. This approach not only caters to dietary restrictions but also highlights sustainability, as tofu production has a lower environmental impact than dairy. Such cheeses are ideal for spreading on crackers or melting into sauces, offering versatility in both flavor and use.

When incorporating these cheeses into dishes, consider their intensity. A gochujang-washed rind cheese pairs well with mild accompaniments like honey or plain crackers to balance its heat. For a more adventurous pairing, try black sesame-crusted halloumi in a grilled cheese sandwich with hoisin sauce for a sweet-savory contrast. For dessert, pandan-infused ricotta can be layered with coconut flakes and mango for a tropical twist. The goal is to let the cheese’s unique profile shine while complementing, not competing with, other ingredients.

In conclusion, modern Asian cheese innovations are redefining what cheese can be, merging cultural heritage with global techniques. These creations are not just products but stories, bridging traditions and tastes. Whether you’re a cheesemaker, chef, or enthusiast, exploring these hybrids opens up a world of possibilities. Start small—experiment with a miso glaze on your next batch of mozzarella or sprinkle furikake on fresh chèvre. The future of cheese is here, and it’s deliciously diverse.

Discover Hamburg NY's Best Cheese Shops: A Tasty Guide

You may want to see also

Regional Cheese Specialties: Focus on specific Asian regions known for their distinct cheese varieties and recipes

Asia, often overlooked in the global cheese narrative, boasts a rich tapestry of regional cheese specialties that reflect local traditions, ingredients, and techniques. From the fermented curds of Mongolia to the smoked delights of India, these cheeses challenge the notion that cheese is solely a Western creation. Let’s explore specific Asian regions where cheese is not just a food but a cultural cornerstone.

Mongolia: The Land of Airag and Byaslag

In Mongolia, cheese is deeply intertwined with nomadic life. Byaslag, a soft, creamy cheese made from cow or yak milk, is a staple in the harsh steppe climate. The process begins with fermenting milk into airag (a mildly alcoholic beverage), which is then curdled to produce byaslag. This cheese is often aged in animal skins, imparting a unique earthy flavor. For those looking to replicate this at home, start by fermenting whole milk with a culture like kefir grains for 24 hours, then heat gently to separate curds. The result is a versatile cheese perfect for crumbling over salads or melting into dumplings.

India: The Smoky Allure of Kalari

In the northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh, Kalari cheese is a testament to India’s diverse culinary heritage. Made from cow or buffalo milk, Kalari is smoked over pinewood fires, giving it a distinct aroma and firm texture. This cheese is often paired with local dishes like momos or simply grilled and served with chutney. To smoke your own Kalari-inspired cheese, use a home smoker with pinewood chips, maintaining a temperature of 60°C for 2–3 hours. The smoking process not only preserves the cheese but also adds a layer of complexity that elevates its flavor profile.

Tibet: The Nutty Delight of Chura Kampo

Tibetan cuisine features Chura Kampo, a hard, nutty cheese made from yak milk. This cheese is traditionally dried in the sun and sliced thinly, making it a portable snack for high-altitude travelers. Its production involves boiling milk, adding rennet, and pressing the curds until firm. For a modern twist, grate Chura Kampo over roasted vegetables or use it as a topping for soups. Its long shelf life and rich flavor make it a practical addition to any pantry, especially for those seeking gluten-free, high-protein options.

Philippines: The Tangy Charm of Kesong Puti

In the Philippines, Kesong Puti is a fresh, soft cheese made from carabao milk. Its simplicity—coagulated milk wrapped in banana leaves—belies its tangy, slightly salty taste. This cheese is often enjoyed for breakfast with pandesal (bread rolls) or used in desserts. To make Kesong Puti at home, heat carabao or buffalo milk to 37°C, add vinegar or lemon juice, and let it curdle for 10 minutes. Drain the whey, press the curds, and wrap in banana leaves for a touch of authenticity.

These regional specialties not only highlight Asia’s cheese diversity but also offer a gateway to understanding the continent’s culinary ingenuity. Whether you’re a cheese enthusiast or a home cook, exploring these varieties promises a journey of discovery and delight.

Discover Big Cheese Locations in Toontown Rewritten: A Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, there are several traditional Asian cheeses, such as Rushan from Xinjiang, China, Chhurpi from the Himalayas, and Byaslag from Mongolia.

Popular Asian cheeses include Quranag from Afghanistan, Panir (a soft cheese used in Indian cuisine), and Kesong Puti from the Philippines.

Asian cheeses often have distinct flavors and textures compared to Western varieties. For example, Chhurpi is hard and chewy, while Kesong Puti is mild and creamy, differing from aged or sharp Western cheeses.

While some Asian cheeses like Panir are commonly found in international markets, others like Rushan or Chhurpi are less available outside their regions of origin but can sometimes be purchased online or in specialty stores.