Aging cheese is a centuries-old practice that transforms raw dairy into a complex, flavorful, and textured food product. While it may seem unusual to associate aging with cheese, this process is essential for developing the unique characteristics of varieties like cheddar, Parmesan, and Gouda. Unlike humans, cheese does not age in the biological sense but undergoes a controlled transformation through microbial activity, enzymatic reactions, and environmental factors. During aging, bacteria and molds break down proteins and fats, creating distinct flavors, aromas, and textures. This deliberate aging process, often referred to as ripening, is a testament to human ingenuity in crafting diverse culinary experiences from a simple ingredient.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Aging cheese is the process of allowing cheese to mature over time, developing its flavor, texture, and aroma. |

| Purpose | Enhances flavor complexity, improves texture, reduces moisture content, and develops a rind. |

| Duration | Varies from a few weeks to several years, depending on the cheese type. |

| Environment | Controlled conditions with specific temperature, humidity, and airflow. |

| Microbial Role | Bacteria and molds play a crucial role in breaking down proteins and fats, contributing to flavor development. |

| Common Cheeses | Cheddar, Parmesan, Gouda, Blue Cheese, Gruyère, and Brie. |

| Texture Changes | Becomes firmer, crumbly, or creamy, depending on the cheese type. |

| Flavor Changes | Develops nutty, sharp, tangy, or earthy flavors. |

| Rind Formation | Some aged cheeses develop a natural rind, which can be edible or non-edible. |

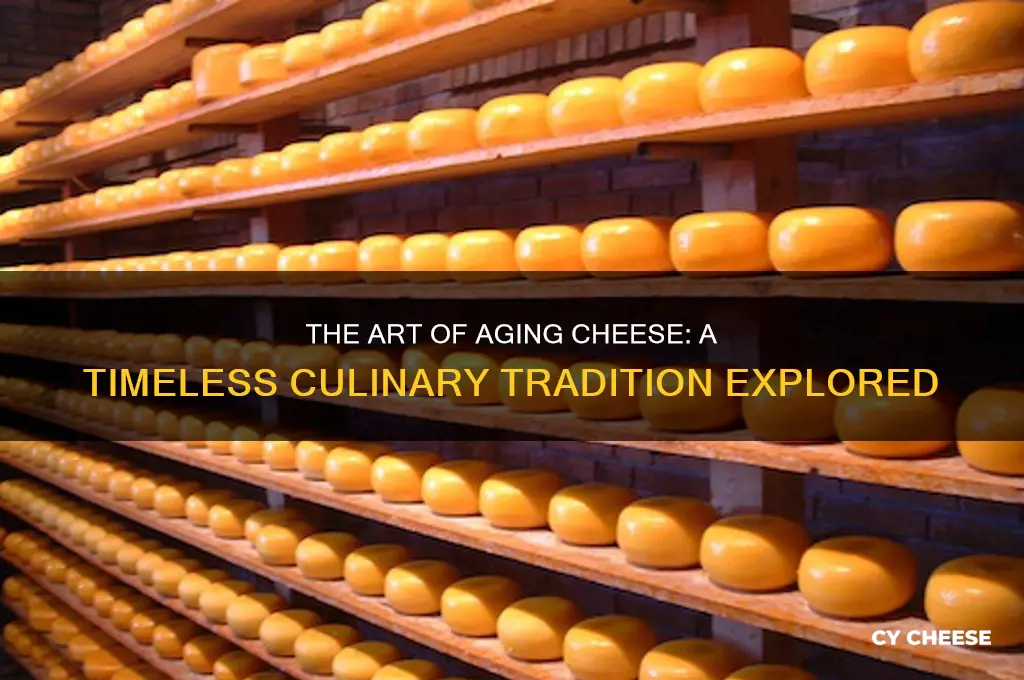

| Storage | Aged cheeses are often stored in caves, cellars, or specialized aging rooms. |

| Health Benefits | Aged cheeses are often higher in protein and lower in lactose compared to fresh cheeses. |

| Economic Impact | Aged cheeses are typically more expensive due to longer production times and labor-intensive processes. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Cheese Aged: Hard, semi-hard, blue, and soft cheeses age differently due to moisture content

- Aging Environment: Temperature, humidity, and airflow control mold growth and flavor development

- Aging Time: Duration varies from weeks to years, impacting texture and taste intensity

- Mold Role: Beneficial molds like Penicillium contribute to unique flavors and textures

- Aging Techniques: Natural cave aging vs. modern controlled environments affect final product quality

Types of Cheese Aged: Hard, semi-hard, blue, and soft cheeses age differently due to moisture content

Cheese aging is an art that transforms curds into complex, flavorful masterpieces, but not all cheeses follow the same path. The moisture content of a cheese dictates its aging process, determining how it develops texture, flavor, and aroma. Hard cheeses, like Parmigiano-Reggiano, start with a moisture content of around 30-35%, allowing them to age for years in controlled environments. This low moisture level prevents spoilage and encourages the growth of beneficial bacteria and enzymes, resulting in a dense, crumbly texture and deep, nutty flavors.

Semi-hard cheeses, such as Cheddar or Gruyère, strike a balance with 40-50% moisture content. This middle ground permits a moderate aging period, typically 2 to 12 months, during which the cheese develops a firmer texture and sharper taste. The higher moisture compared to hard cheeses means they require careful humidity control to avoid mold or drying out. These cheeses are versatile, transitioning from mild and creamy when young to robust and crystalline when aged.

Blue cheeses, like Stilton or Roquefort, defy categorization with their distinctive veining and 50-70% moisture content. Aging for these cheeses involves introducing Penicillium mold spores, which thrive in the damp interior. The moisture allows the mold to spread, creating pockets of pungent, creamy flavor. Aging times range from 2 to 6 months, with the cheese becoming more intense and crumbly as it matures. Proper ventilation is critical to prevent excess moisture from causing spoilage.

Soft cheeses, such as Brie or Camembert, age quickly due to their high moisture content, often exceeding 50%. Their thin rinds and creamy interiors limit aging to 4-8 weeks, as longer periods risk spoilage. During this brief window, surface molds bloom, contributing earthy, mushroom-like flavors. These cheeses are best enjoyed young, when their textures are velvety and their flavors delicate. For optimal aging, maintain a cool, humid environment to encourage rind development without drying the interior.

Understanding how moisture content drives aging allows cheese enthusiasts to appreciate the nuances of each type. Hard cheeses reward patience, semi-hard cheeses offer versatility, blue cheeses deliver boldness, and soft cheeses provide immediate gratification. By controlling temperature, humidity, and time, anyone can master the aging process, turning simple curds into extraordinary culinary experiences.

Where to Find Red Wax Gouda Cheese in Apple Valley, CA 92308

You may want to see also

Aging Environment: Temperature, humidity, and airflow control mold growth and flavor development

Cheese aging is a delicate dance between science and art, where temperature, humidity, and airflow play pivotal roles in shaping flavor, texture, and aroma. These environmental factors dictate the growth of molds and bacteria, which are essential for transforming a simple curd into a complex, nuanced cheese. Understanding their interplay allows both artisanal cheesemakers and enthusiasts to control the aging process, ensuring consistency and quality.

Temperature acts as the maestro of the aging environment, influencing enzymatic activity and microbial growth. Most cheeses age optimally between 50°F and 55°F (10°C–13°C). Harder cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano thrive at slightly higher temperatures, around 59°F (15°C), which accelerates protein breakdown and intensifies flavor. Conversely, softer cheeses such as Brie require cooler temperatures, around 45°F–50°F (7°C–10°C), to slow rind development and maintain a creamy interior. Deviations of just a few degrees can halt or accelerate aging, leading to off-flavors or texture defects. For home agers, a wine fridge with precise temperature control is an ideal investment.

Humidity is the unsung hero of cheese aging, directly affecting moisture content and rind formation. Ideal relative humidity levels range from 80% to 90%, depending on the cheese. High humidity prevents cheeses from drying out, while lower levels (70%–75%) are suitable for semi-hard varieties like Cheddar. Too much moisture encourages unwanted molds or slime, while too little causes the cheese to crack or become brittle. Regularly misting the cheese or using a humidifier can help maintain optimal conditions. For example, a wheel of Camembert requires consistent high humidity to develop its signature velvety rind.

Airflow is the often-overlooked factor that balances moisture and prevents stagnation. Proper ventilation ensures even distribution of temperature and humidity, preventing pockets of excess moisture where harmful bacteria can thrive. However, too much airflow can dehydrate the cheese. Aging rooms should have passive airflow, such as strategically placed vents or fans set on low. For home aging, placing cheese on wire racks allows air to circulate beneath, while wrapping it loosely in cheese paper permits breathability without excessive drying.

Mastering these environmental controls requires patience and observation. Small-scale experiments, such as aging two identical cheeses at slightly different temperatures or humidity levels, can reveal their impact on flavor and texture. For instance, a Gruyère aged at 55°F with 85% humidity will develop a more pronounced nutty flavor and eyes (holes) compared to one aged at 50°F with 80% humidity. By fine-tuning these variables, cheesemakers can craft distinct profiles, turning aging from a passive process into an active art form.

Should Kraft Cheese Slices Be Refrigerated? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Aging Time: Duration varies from weeks to years, impacting texture and taste intensity

The duration of cheese aging is a critical factor that transforms a simple dairy product into a complex culinary experience. From a few weeks to several years, the aging process, or affinage, dictates the cheese's texture, flavor intensity, and overall character. For instance, a young cheese like fresh mozzarella, aged for just a few weeks, retains its soft, pliable texture and mild, milky taste. In contrast, a cheese aged for years, such as a well-matured Parmigiano-Reggiano, develops a hard, granular texture and a deep, nutty flavor profile that can command a premium price.

Aging time is not arbitrary; it is a deliberate choice that cheesemakers make to achieve specific sensory outcomes. The science behind this process involves the breakdown of proteins and fats by bacteria and enzymes, which intensifies flavors and alters textures. For example, a semi-hard cheese like Cheddar aged for 6 months will have a smoother texture and milder tang compared to its 2-year-aged counterpart, which becomes crumbly and sharply flavorful. This progression highlights how time acts as both a sculptor and a flavor enhancer, turning the same base ingredients into vastly different products.

Practical considerations also come into play when determining aging duration. Longer aging periods require more storage space, precise humidity and temperature control, and increased risk of spoilage. For home cheesemakers, aging a cheese for 2–3 months in a dedicated fridge with consistent conditions (around 50–55°F and 85% humidity) is achievable and rewarding. However, replicating the environment needed for multi-year aging, such as that of a traditional cave, is challenging without professional equipment. Thus, the aging time often reflects a balance between desired outcomes and logistical constraints.

The impact of aging time on cheese is not just a matter of taste but also of cultural and economic significance. In regions like France and Italy, aged cheeses are celebrated as artisanal masterpieces, with aging durations proudly displayed on labels. A 12-month aged Comté or a 36-month aged Gouda are not just foods but symbols of tradition and craftsmanship. For consumers, understanding aging time allows for informed choices—whether selecting a young, creamy Brie for a dinner party or investing in an aged Gruyère for a special recipe. This knowledge bridges the gap between production and appreciation, enriching the cheese-eating experience.

Finally, experimenting with cheeses of varying ages can be an educational and sensory journey. Start with a tasting lineup: a young (2–4 weeks), medium (3–6 months), and old (1–5 years) version of the same cheese type. Note how the texture evolves from supple to firm, and the flavor deepens from subtle to robust. This hands-on approach demystifies the aging process, revealing how time is not just a measure but a transformative force in the world of cheese. Whether you’re a casual enthusiast or a dedicated aficionado, appreciating the role of aging time adds a new layer of depth to every bite.

Papa John's Jalapeño Bites: Unveiling the Cheesy Secret Inside

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mold Role: Beneficial molds like Penicillium contribute to unique flavors and textures

Molds are not merely spoilers of food but artisans in the world of cheese, transforming ordinary curds into complex, flavorful masterpieces. Beneficial molds like *Penicillium camemberti* and *Penicillium roqueforti* are the unsung heroes behind classics such as Camembert, Brie, and Blue Cheese. These molds introduce enzymes that break down fats and proteins, creating creamy textures and nuanced flavors ranging from earthy to sharp. Without them, many of the cheeses we cherish would lack their signature character.

Consider the process of aging cheese with mold: it’s a delicate dance of time, temperature, and humidity. For example, *Penicillium camemberti* is applied to the surface of Camembert, where it thrives in a cool, moist environment (around 50°F and 90% humidity). Over 3–4 weeks, the mold forms a bloomy rind, softening the interior and imparting a rich, buttery flavor. In contrast, *Penicillium roqueforti* is introduced internally to Blue Cheese, often through piercing the curds with needles to allow oxygen penetration. This mold thrives in higher temperatures (around 55°F) and produces veins of pungent, tangy flavor over 2–3 months.

The role of mold extends beyond flavor—it acts as a preservative, inhibiting harmful bacteria and extending the cheese’s shelf life. For home cheesemakers, understanding mold behavior is crucial. Start by sourcing high-quality spores (available as commercial cultures) and maintain strict hygiene to prevent contamination. Monitor aging conditions closely; even slight deviations in temperature or humidity can alter mold growth and, consequently, the cheese’s outcome. For instance, too much moisture can lead to ammonia flavors, while too little can halt mold development.

Comparatively, mold-ripened cheeses stand apart from their unmolded counterparts. While Cheddar or Swiss rely on bacterial cultures for aging, mold-ripened cheeses offer a distinct sensory experience. The mold’s enzymatic activity creates a spectrum of textures—from the oozing interior of a ripe Brie to the crumbly veins of Stilton. This diversity highlights the mold’s versatility and its ability to elevate cheese from a staple to a gourmet delight.

In practice, experimenting with mold-aged cheeses can be rewarding. Begin with a simple project like Camembert, which requires minimal equipment and yields results in under a month. Invest in a small aging fridge to control conditions, and keep detailed logs of temperature, humidity, and visual changes. Remember, mold is not an adversary but a collaborator—treat it with respect, and it will reward you with cheeses that tell a story of craftsmanship and patience.

Crispy Cheese Curds: Mastering Turkey Fryer Techniques for Perfect Results

You may want to see also

Aging Techniques: Natural cave aging vs. modern controlled environments affect final product quality

Cheese aging, a centuries-old practice, has evolved from relying on natural cave environments to utilizing modern, controlled settings. Each method imparts distinct characteristics to the final product, influencing flavor, texture, and aroma. Natural cave aging, with its inherent variability, offers a unique terroir-driven profile, while modern controlled environments prioritize consistency and efficiency. Understanding these techniques reveals how tradition and innovation shape the cheese we savor.

Natural cave aging leverages the earth’s stable temperature (typically 8–12°C) and humidity (85–95%) to slowly transform cheese. Caves provide a microbiome of native molds, yeasts, and bacteria that colonize the rind, contributing complex, earthy flavors. For example, French Comté aged in Jura Mountain caves develops nutty, fruity notes due to the region’s specific microflora. However, this method is labor-intensive, requires extensive space, and yields unpredictable results due to environmental fluctuations. Artisan cheesemakers often reserve cave aging for premium products, accepting higher costs for its artisanal appeal.

In contrast, modern controlled environments use climate-regulated rooms equipped with humidity sensors, air circulation systems, and UV lighting to mimic cave conditions. These facilities maintain precise parameters—temperature within ±1°C and humidity at 88–92%—ensuring uniformity across batches. For instance, Dutch Gouda aged in such settings consistently achieves a buttery texture and mild tang. While lacking the microbial diversity of caves, controlled aging allows for scalability and reduced risk of spoilage. Manufacturers can also introduce specific cultures to tailor flavors, such as adding *Penicillium camemberti* for a creamy Brie-like finish.

The choice between methods hinges on the desired outcome. Natural cave aging excels in producing cheeses with nuanced, place-specific qualities, ideal for connoisseurs seeking depth and character. Modern environments cater to mass production, delivering reliable results for everyday consumption. Hybrid approaches, where cheese starts in caves and finishes in controlled rooms, are gaining traction, balancing tradition with practicality. For home cheesemakers, replicating cave conditions requires a wine fridge set to 10°C and a humidifier, though achieving microbial complexity remains challenging without a natural environment.

Ultimately, both techniques have merit, reflecting the duality of craftsmanship and technology in cheese aging. Whether savoring a cave-aged Gruyère or a factory-perfected Cheddar, the method of aging is as much a part of the story as the cheese itself.

Subway Italian BMT's Default Cheese: A Tasty Surprise Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, people age cheese as part of the cheesemaking process to develop flavor, texture, and complexity.

Aging times vary widely, from a few weeks for fresh cheeses to several years for hard cheeses like Parmesan.

During aging, bacteria and molds break down the cheese, transforming its texture, flavor, and moisture content.

Yes, cheese can be aged at home with proper temperature, humidity control, and storage conditions.