The question of whether to cut the red or green wax off of cheese often arises when encountering cheeses like Gouda or Edam, which are traditionally coated in a protective wax layer. This wax serves to preserve the cheese by preventing moisture loss and inhibiting mold growth during aging. While the wax itself is not meant to be eaten, the choice of cutting the red or green wax is purely aesthetic, as both colors are commonly used without any difference in flavor or quality. The decision typically comes down to personal preference or the specific presentation desired, though it’s essential to remove the wax entirely before consuming the cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Question | Do you cut the red or green off of cheese? |

| Context | Refers to the wax coating on certain cheeses, typically Gouda or Edam. |

| Red Wax | Traditionally used for younger cheeses (aged less than 6 months). |

| Green Wax | Traditionally used for older cheeses (aged 6 months or more). |

| Edibility | The wax is not meant to be eaten; it is a protective coating. |

| Removal | Cut off the wax before consuming the cheese. |

| Modern Variations | Some cheeses may use different colors or no wax at all. |

| Common Misconception | The color of the wax does not indicate the flavor or type of cheese, only the age. |

| Storage | Wax helps preserve the cheese by preventing moisture loss and mold growth. |

| Environmental Impact | Cheese wax is typically food-grade and can be recycled or reused. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Understanding Cheese Rind Types: Differentiating natural, waxed, and bloomy rinds to guide cutting decisions

- Red Wax vs. Green Mold: Identifying edible coatings and harmful growths on cheese surfaces

- Cutting Techniques for Rinds: Proper methods to preserve flavor and texture when slicing cheese

- Edible vs. Non-Edible Parts: Determining which cheese components are safe to consume or discard

- Cheese Storage Tips: How to handle and store cheese to maintain freshness and quality

Understanding Cheese Rind Types: Differentiating natural, waxed, and bloomy rinds to guide cutting decisions

Cheese rinds are not one-size-fits-all. Understanding the type of rind on your cheese is crucial for proper cutting and enjoyment. Natural, waxed, and bloomy rinds each serve distinct purposes, from protecting the cheese to enhancing its flavor, and require different handling techniques.

Natural rinds, often found on aged cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano or aged Goudas, are edible but tough. These rinds develop as the cheese dries and hardens, creating a protective barrier against moisture loss. When cutting cheeses with natural rinds, such as a 24-month aged Parmesan, remove the rind only if it’s excessively hard or unpalatable. For younger, more pliable natural rinds, consider leaving them on, as they can add a nutty or earthy flavor. Use a sharp knife to slice through the rind cleanly, ensuring you don’t waste the cheese beneath.

Waxed rinds, commonly seen on cheeses like Cheddar or Gouda, are applied to preserve moisture and prevent mold growth. These rinds are not edible and should always be removed before serving. To cut waxed cheese, start by peeling back the wax with a knife or your fingers, then slice the cheese as desired. Be cautious not to leave small wax fragments behind, as they can be a choking hazard. For semi-hard waxed cheeses, aim for slices no thicker than ¼ inch to balance flavor and texture.

Bloomy rinds, characteristic of cheeses like Brie or Camembert, are soft, edible, and covered in a velvety white mold. These rinds are integral to the cheese’s flavor and texture, contributing a creamy, earthy profile. When serving bloomy rind cheeses, leave the rind intact unless it’s overly ammoniated or unappealing. For optimal enjoyment, let the cheese sit at room temperature for 30–60 minutes before cutting. Use a cheese wire or thin knife to slice through the rind and interior without squashing the delicate paste.

In summary, the decision to cut or keep a cheese rind depends on its type. Natural rinds are often edible but may need trimming; waxed rinds are always removed; and bloomy rinds are typically enjoyed as part of the cheese. By understanding these distinctions, you’ll enhance both the presentation and flavor of your cheese selections.

Can Kids Enjoy Subway's Herb and Cheese Bread in Meals?

You may want to see also

Red Wax vs. Green Mold: Identifying edible coatings and harmful growths on cheese surfaces

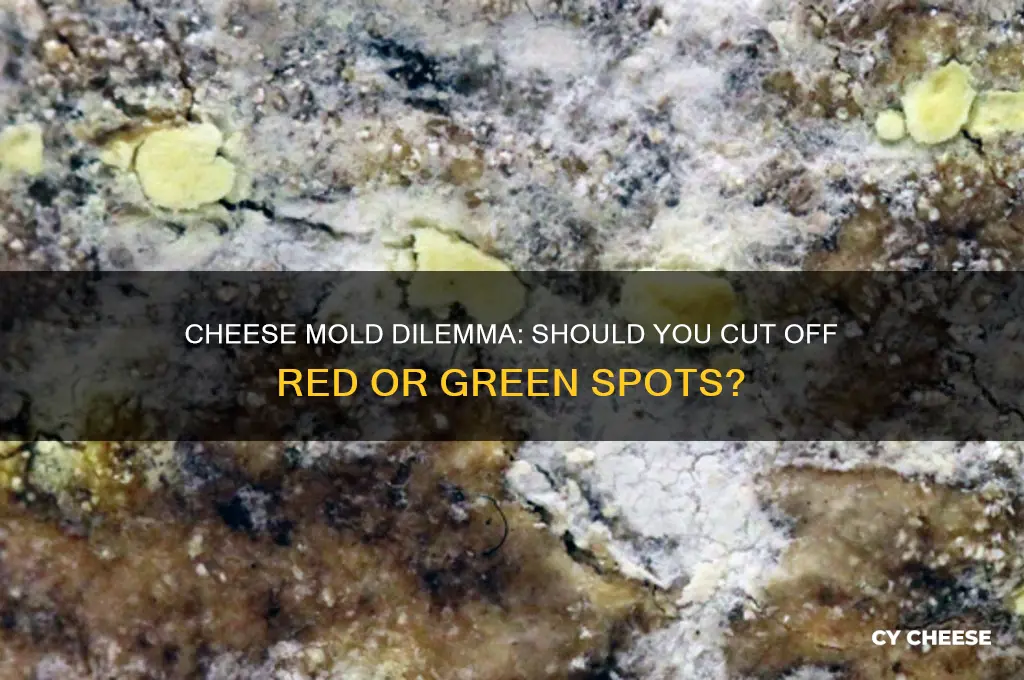

Cheese enthusiasts often encounter a colorful dilemma: red wax or green mold. While both are surface treatments, their purposes and implications differ drastically. Red wax, commonly found on cheeses like Gouda or Edam, serves as a protective barrier, preserving moisture and flavor during aging. It’s entirely non-toxic and should be removed before consumption. Green mold, however, is a natural occurrence on certain cheeses like Brie or Camembert, contributing to their distinctive taste and texture. Yet, not all green growths are benign—some indicate spoilage. Understanding these distinctions ensures both safety and enjoyment.

To differentiate between edible coatings and harmful growths, inspect the cheese’s surface closely. Red wax is uniform, smooth, and artificially applied, often with a label indicating its presence. Peel it off carefully, as ingesting wax can cause digestive discomfort. Green mold on cheeses like Brie should appear powdery, white, or pale green near the rind, with a creamy interior. If the mold is dark green, black, or fuzzy, or if the cheese smells ammonia-like, discard it immediately. For aged cheeses like Stilton, blue veins are intentional and safe, but green mold is a red flag.

When handling moldy cheeses, follow specific guidelines. Soft cheeses with unintended mold should be discarded entirely, as their high moisture content allows spores to penetrate deeply. Hard cheeses like Cheddar or Parmesan can be salvaged by cutting off the moldy portion plus an additional inch, ensuring no spores remain. Always use a clean knife to avoid cross-contamination. For pregnant individuals or those with weakened immune systems, err on the side of caution and avoid mold-ripened cheeses altogether, opting for pasteurized, mold-free varieties.

The debate of red wax versus green mold highlights the importance of informed cheese consumption. While red wax is a harmless, removable coating, green mold requires careful scrutiny. Educating oneself on cheese types and their intended appearances empowers consumers to make safe choices. Whether enjoying a wax-encased Gouda or a mold-ripened Camembert, understanding these surface treatments transforms a potential hazard into a delightful culinary experience. Always prioritize safety, but don’t shy away from exploring the diverse world of cheese.

How to Perfectly Heat Tostitos Fiesta Bean and Cheese Dip

You may want to see also

Cutting Techniques for Rinds: Proper methods to preserve flavor and texture when slicing cheese

The red or green wax coating on certain cheeses, like Gouda or Edam, is not meant to be eaten. It’s a protective layer, and removing it improperly can compromise the cheese’s texture and flavor. Cutting through the wax with a knife dulls the blade and risks leaving wax fragments in the cheese. Instead, use a cheese plane or a sharp paring knife to carefully slice off the desired portion, leaving the wax intact on the remainder. This preserves the cheese’s integrity and ensures a clean cut.

For cheeses with natural rinds, such as Brie or Camembert, the approach differs. These rinds are edible and contribute to the cheese’s flavor profile. When slicing, always cut from the center outward to maintain the rind’s structure. For softer cheeses, use a warm, thin-bladed knife to prevent tearing. Harder rinds, like those on aged cheddars, require a firmer hand and a sharper blade. The goal is to minimize damage to the rind while achieving even slices, ensuring each piece retains its intended balance of flavor and texture.

Aged cheeses with thick, hard rinds, such as Parmesan or Gruyère, demand precision. Start by scoring the rind with a sharp knife, then use a cheese wire or heavy-duty string to cut through cleanly. This method prevents crumbling and preserves the cheese’s dense texture. For smaller portions, a microplane or grater can be used to shave off thin pieces without disturbing the rind. Always store the cheese with the rind intact to prevent moisture loss and maintain its longevity.

When dealing with washed-rind cheeses, like Époisses or Taleggio, the rind is a critical component of the flavor but can be overpowering. To preserve the cheese’s character, trim only the edges of the rind if desired, leaving the majority intact. Use a long, thin blade to avoid crushing the soft interior. For serving, cut the cheese into portions that include both the rind and the paste, allowing guests to experience the full flavor spectrum. Proper cutting techniques here ensure the rind enhances, rather than overwhelms, the cheese.

In all cases, the key to preserving flavor and texture lies in respecting the rind’s purpose. Whether it’s a protective wax layer, an edible natural covering, or a flavor-enhancing barrier, the right cutting technique ensures the cheese is enjoyed as intended. By using the appropriate tools and methods, you maintain the structural and sensory integrity of the cheese, elevating the experience for every slice.

Aldi Advent Calendar Cheese Variety: Are All 24 Cheeses Unique?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Edible vs. Non-Edible Parts: Determining which cheese components are safe to consume or discard

Cheese, a beloved staple in many diets, often comes with natural or added components that raise questions about edibility. Take, for example, the red wax coating on Gouda or the green mold on certain aged cheeses. While these elements serve specific purposes—wax protects the cheese, and mold contributes to flavor—their consumption is not always advisable. Understanding which parts are safe to eat and which should be discarded is crucial for both enjoyment and health.

From an analytical perspective, the red wax on cheeses like Gouda or Edam is purely functional. It acts as a barrier against moisture loss and contamination during aging. While non-toxic, the wax is not digestible and offers no nutritional value. Ingesting small amounts is generally harmless, but it’s best removed before consumption. Conversely, the green mold on cheeses like Stilton or Roquefort is intentional and edible, contributing to their distinctive flavor profiles. However, unintended mold growth on other cheeses, such as green spots on Brie or Camembert, indicates spoilage and should be discarded entirely.

Instructively, here’s a practical guide: for wax-coated cheeses, use a sharp knife to carefully slice off the wax, ensuring no residue remains. For mold-ripened cheeses, inspect the type of mold. If it’s part of the cheese’s design (e.g., blue or green veins in blue cheese), it’s safe to eat. If the mold is fuzzy, discolored, or appears on cheeses not meant to have mold, discard the entire piece, as harmful bacteria may have developed. For children, pregnant individuals, or those with compromised immune systems, err on the side of caution and avoid any cheese with visible mold.

Persuasively, consider the sensory experience. The red wax on Gouda, while inedible, enhances the cheese’s visual appeal and preserves its creamy texture. Removing it allows the cheese’s true flavor to shine. Similarly, the green mold in blue cheeses is a testament to artisanal craftsmanship, offering complex flavors that elevate dishes. By discerning edible from non-edible parts, you not only ensure safety but also maximize enjoyment. Think of it as respecting the cheese’s intended design—whether it’s the protective wax or the flavorful mold.

Comparatively, the approach to cheese components differs across cultures. In Europe, the rind of cheeses like Brie is often consumed, valued for its texture and flavor. In contrast, American consumers frequently discard rinds due to unfamiliarity or preference. Similarly, while green mold on blue cheese is celebrated in Western cuisines, unintended mold is universally avoided. This highlights the importance of context: what’s edible in one cheese may not be in another. Always research or consult labels if unsure.

Descriptively, imagine slicing into a wheel of Gouda. The vibrant red wax glistens under the light, a stark contrast to the pale yellow interior. As you remove the wax, the cheese’s rich aroma escapes, inviting you to savor its smoothness. Now picture a wedge of Stilton, its green veins marbling through the crumbly texture. Each bite delivers a pungent, earthy flavor, a direct result of the mold’s role in aging. These sensory details underscore why understanding edibility matters—it’s about preserving the cheese’s integrity and your culinary experience.

Mastering Astel: Cheesing Strategies for Naturalborn of the Void

You may want to see also

Cheese Storage Tips: How to handle and store cheese to maintain freshness and quality

Cheese, a beloved staple in many households, often comes with a wax coating, sometimes red or green, which raises the question: should you cut it off? The answer lies in understanding the purpose of this coating. Wax is primarily used to protect the cheese during aging and transportation, acting as a barrier against mold and moisture loss. When storing cheese at home, however, this protective layer can hinder proper care. Removing the wax allows the cheese to breathe, preventing excess moisture buildup that can lead to spoilage. For optimal freshness, trim the wax before storing, but leave a thin layer intact to maintain some protection without suffocating the cheese.

Proper handling begins with temperature control. Cheese thrives in cool, consistent conditions, ideally between 35°F and 45°F (2°C and 7°C). Refrigeration is essential, but avoid placing cheese in the coldest part of the fridge, such as the back or bottom shelves, where temperatures can fluctuate. Instead, use the lower-middle or deli drawer, which offers more stable conditions. Wrapping cheese correctly is equally crucial. Use wax paper or parchment paper, which allows air circulation, rather than plastic wrap, which traps moisture and accelerates spoilage. For longer storage, consider vacuum-sealed bags or cheese paper, which balances humidity and breathability.

Humidity plays a pivotal role in cheese storage, particularly for harder varieties like cheddar or Parmesan. These cheeses benefit from slightly drier conditions to prevent mold growth, while softer cheeses like Brie or Camembert require higher humidity to maintain their texture. A practical solution is to store different types of cheese separately or use divided containers. For softer cheeses, adding a damp (not wet) paper towel in the storage container can help maintain the desired moisture level. Regularly inspect your cheese for signs of mold, and if spotted, remove it with a knife, cutting at least 1 inch around the affected area to ensure all mold is eliminated.

Rotation and portioning are often overlooked but essential practices. Cheese deteriorates faster once opened, so consume it within 1–2 weeks for softer varieties and 3–4 weeks for harder types. To extend freshness, divide larger blocks into smaller portions and store them individually. Label each portion with the date to ensure you use the oldest cheese first. If you’re storing multiple cheeses, keep strongly flavored varieties like blue cheese separate, as they can transfer their aroma to milder cheeses. For long-term storage, consider freezing, but note that this works best for hard and semi-hard cheeses, as freezing can alter the texture of softer varieties.

Finally, trust your senses. While proper storage can significantly prolong cheese’s life, it’s not foolproof. Always inspect cheese for off smells, slimy textures, or unusual discoloration before consuming. When in doubt, discard it. By combining these storage tips—removing excess wax, controlling temperature and humidity, rotating portions, and using sensory checks—you can maintain the quality and freshness of your cheese, ensuring every bite is as delightful as the first.

Did Anyone Order a Plain Cheese GIF? The Internet's Cheesiest Trend

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese typically does not have red or green parts to cut off. If you're referring to mold, it’s generally advised to cut off at least 1 inch around and below the moldy spot for hard cheeses, and discard soft cheeses entirely if moldy.

Red or green on cheese is usually mold. While some cheeses like Brie or Camembert have edible white mold, red or green mold indicates spoilage and should be avoided.

No, cheese with red or green spots is likely spoiled and should not be consumed, as these colors indicate harmful mold.

Store cheese properly in the refrigerator, wrap it in wax or parchment paper, and avoid using plastic wrap, which can trap moisture and promote mold growth.

For hard cheeses, you can cut off the moldy part plus an extra inch, but soft or semi-soft cheeses with red or green mold should be discarded entirely, as the mold can penetrate deeper.