When comparing the calcium content of aged cheese versus milk, it’s essential to consider both the concentration and bioavailability of calcium in each. Milk is a well-known source of calcium, providing a significant amount per serving, typically around 300 mg per cup, with high bioavailability due to its lactose and vitamin D content. Aged cheese, on the other hand, contains a higher concentration of calcium per gram because the aging process reduces moisture, intensifying its nutrient density. For example, a 30-gram serving of aged cheddar can provide around 200 mg of calcium. However, the bioavailability of calcium in cheese may vary depending on factors like fat content and individual digestion. Ultimately, while aged cheese offers more calcium by weight, milk remains a more practical and efficient source for meeting daily calcium needs due to its lower calorie density and higher volume consumption.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Calcium Content (per 100g) | Aged Cheese: ~700-1,000 mg Milk (whole): ~120 mg |

| Bioavailability | Aged Cheese: Higher due to reduced lactose and easier digestion |

| Lactose Content | Aged Cheese: Very low (most lactose is removed during aging) Milk: Higher (1-5% lactose) |

| Calcium Absorption | Aged Cheese: Better absorption due to lower lactose and fat content |

| Vitamin D Content | Milk (fortified): ~2.5 mcg Aged Cheese: Minimal |

| Protein Content | Aged Cheese: ~25g Milk: ~3.4g |

| Fat Content | Aged Cheese: ~25-30g Milk (whole): ~3.6g |

| Sodium Content | Aged Cheese: ~600-1,000 mg Milk: ~40 mg |

| Caloric Density | Aged Cheese: ~350-400 kcal Milk (whole): ~60 kcal |

| Shelf Life | Aged Cheese: Longer (months to years) Milk: Shorter (days to weeks) |

| Allergen Considerations | Aged Cheese: Lower lactose, suitable for some lactose intolerant Milk: Higher lactose, may cause issues |

| Cost per Serving | Aged Cheese: Generally higher Milk: More affordable |

| Versatility in Diet | Aged Cheese: Limited use (snacks, cooking) Milk: Versatile (drinking, cooking, baking) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Calcium Content Comparison: Aged cheese vs. milk calcium levels analyzed for nutritional value differences

- Bioavailability Factor: How calcium absorption varies between aged cheese and milk consumption

- Serving Size Impact: Calcium intake based on standard servings of cheese and milk

- Nutrient Trade-offs: Comparing calcium alongside other nutrients in aged cheese vs. milk

- Health Implications: Effects of aged cheese and milk calcium on bone health and diet

Calcium Content Comparison: Aged cheese vs. milk calcium levels analyzed for nutritional value differences

Calcium is a cornerstone nutrient for bone health, but not all dairy sources are created equal. Aged cheese, celebrated for its rich flavor and texture, often raises questions about its calcium content compared to milk. A direct comparison reveals that while milk is a more concentrated source of calcium by volume, aged cheese can pack a surprising punch due to its density. For instance, 100 grams of aged cheddar contains approximately 721 mg of calcium, whereas the same weight of whole milk provides around 120 mg. This disparity highlights the importance of considering portion sizes and nutritional density when evaluating calcium intake.

Analyzing the nutritional value differences, it’s clear that aged cheese’s higher calcium content per gram stems from its concentrated form. During the aging process, moisture evaporates, leaving behind a denser product with amplified nutrient levels. However, this concentration comes with trade-offs. Aged cheese is also higher in calories, fat, and sodium compared to milk, which may influence dietary choices, especially for those monitoring specific macronutrients. For example, a 30-gram serving of aged Parmesan delivers about 331 mg of calcium but also contains 120 calories, whereas a 240-ml glass of milk provides 300 mg of calcium with only 150 calories.

Practical tips for optimizing calcium intake depend on individual dietary needs and preferences. For those seeking a calcium boost without excess calories, milk remains a straightforward choice. However, aged cheese can be a valuable alternative for individuals with lactose intolerance, as the aging process reduces lactose content significantly. Incorporating small portions of aged cheese into meals—such as grating Parmesan over salads or adding cheddar to sandwiches—can enhance calcium intake without overloading on calories. Pairing these choices with calcium-rich non-dairy sources like leafy greens or fortified plant milks ensures a balanced approach.

A comparative analysis underscores that neither aged cheese nor milk is universally superior; the choice depends on context. Milk is ideal for those prioritizing hydration and lower calorie density, while aged cheese suits those seeking nutrient-dense, lactose-reduced options. For children and adolescents, milk may be preferable due to its fluid content and role in overall hydration, whereas older adults might benefit from aged cheese’s higher calcium concentration to combat age-related bone density loss. Ultimately, understanding these differences empowers informed decisions tailored to specific health goals and dietary constraints.

Creative Ways to Enjoy Baked Lemon Ricotta Cheese Deliciously

You may want to see also

Bioavailability Factor: How calcium absorption varies between aged cheese and milk consumption

Calcium content alone doesn’t determine its benefit to your body. Bioavailability—the proportion of a nutrient that’s actually absorbed and used—plays a critical role. While aged cheese and milk both contain calcium, their bioavailability differs due to factors like fat content, protein structure, and pH levels. For instance, aged cheese has a higher fat content, which can enhance calcium absorption by facilitating the formation of micelles, structures that improve nutrient uptake in the intestines.

Consider this: a 30-gram serving of aged cheddar provides approximately 200 mg of calcium, while an 8-ounce glass of milk contains around 300 mg. However, studies suggest that the calcium in cheese may be absorbed 30-50% more efficiently than that in milk. This is partly because the fermentation process in cheese breaks down proteins, making calcium more accessible. For adults over 50, who require 1,200 mg of calcium daily, incorporating aged cheese could be a strategic way to meet this need without relying solely on milk.

To maximize calcium absorption from aged cheese, pair it with vitamin D-rich foods like fatty fish or fortified yogurt. Vitamin D enhances calcium uptake by improving intestinal absorption. Conversely, avoid consuming high-oxalate foods (e.g., spinach, almonds) alongside cheese, as oxalates can bind to calcium and reduce its bioavailability. For lactose-intolerant individuals, aged cheese is a particularly advantageous option, as the aging process reduces lactose content while retaining calcium in a highly absorbable form.

Practical tip: For children and adolescents, who need 1,300 mg of calcium daily for bone development, a balanced approach is best. Combine milk with small portions of aged cheese to leverage both the higher calcium content of milk and the superior bioavailability of cheese. For example, a morning smoothie with milk and a mid-day snack of cheese cubes can optimize calcium intake across age groups.

In summary, while milk provides more calcium per serving, aged cheese offers a bioavailability edge. Tailoring your diet to include both can ensure you’re not just consuming calcium but effectively utilizing it. Whether you’re a teenager, adult, or senior, understanding this distinction allows you to make informed choices for bone health and overall well-being.

Lectins in Bananas, Cheese, and Crackers: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

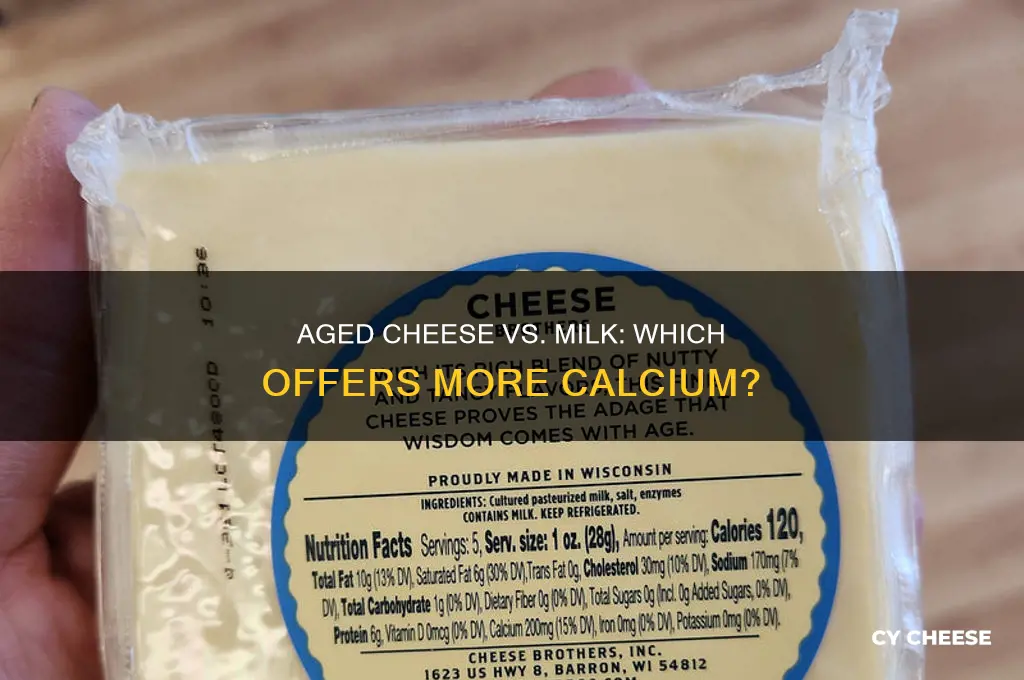

Serving Size Impact: Calcium intake based on standard servings of cheese and milk

Calcium content in food is often measured per 100 grams, but real-world consumption relies on standard serving sizes. A typical serving of milk is 1 cup (240 ml), while cheese servings vary—1 ounce (28 grams) for hard cheeses like cheddar and 2 tablespoons (30 grams) for grated varieties. These standardized portions are key to understanding calcium intake differences between milk and aged cheese. For instance, 1 cup of whole milk contains approximately 276 mg of calcium, whereas 1 ounce of aged cheddar provides around 204 mg. This disparity highlights how serving size directly influences calcium contribution to daily intake.

Consider the dietary needs of different age groups. Adults aged 19–50 require 1,000 mg of calcium daily, while women over 50 and men over 70 need 1,200 mg. To meet these goals, an adult would need roughly 3.6 cups of milk or 4.9 ounces of aged cheddar daily. However, such quantities are impractical for cheese due to its calorie density—4.9 ounces of cheddar contains about 700 calories, compared to 460 calories in 3.6 cups of whole milk. This example illustrates how serving size and nutritional density must be balanced when relying on cheese as a calcium source.

Practical tips can help optimize calcium intake from both milk and cheese. For milk, choose fortified plant-based alternatives if lactose intolerant, ensuring they provide 270–300 mg of calcium per cup. For cheese, pair small portions with lower-calorie foods like salads or vegetables to maximize calcium without excessive calories. For example, sprinkling 1 ounce of grated aged cheese (220 mg calcium) over a vegetable dish adds nutritional value without overloading on fat or calories. Such strategies ensure calcium goals are met within a balanced diet.

A comparative analysis reveals that while milk provides more calcium per standard serving, cheese’s higher calcium density per gram offers a concentrated alternative. For instance, 100 grams of aged cheddar contains 721 mg of calcium, surpassing the 116 mg in 100 grams of whole milk. However, cheese’s smaller serving sizes limit its calcium contribution in practical terms. This underscores the importance of considering both serving size and calcium density when comparing milk and cheese as dietary sources. Tailoring intake to individual needs and preferences ensures calcium goals are achieved efficiently.

Dairy-Free Cheese Options: Exploring Non-Dairy Alternatives Without Proteins

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Nutrient Trade-offs: Comparing calcium alongside other nutrients in aged cheese vs. milk

Aged cheese and milk are both dairy staples, but their nutrient profiles diverge significantly due to the aging process. While milk is a liquid, fresh product, aged cheese undergoes fermentation and dehydration, concentrating certain nutrients while reducing others. This transformation raises a critical question: does the calcium content in aged cheese surpass that of milk, and if so, at what cost to other essential nutrients?

Analyzing Calcium Content:

Aged cheeses like Parmesan or Cheddar boast higher calcium concentrations per gram compared to milk. For instance, 100 grams of Parmesan provides approximately 1,300 mg of calcium, whereas the same weight of whole milk contains around 120 mg. This disparity arises because aging removes moisture, intensifying calcium density. However, portion sizes matter: a typical serving of cheese (30 grams) delivers about 390 mg of calcium, still substantial but less than the 300 mg in a 240 ml glass of milk. Thus, while aged cheese is calcium-rich, achieving daily calcium goals (1,000–1,200 mg for adults) may require larger servings, potentially increasing calorie and fat intake.

Nutrient Trade-offs Beyond Calcium:

The aging process alters more than just calcium. Milk retains higher levels of vitamin B12, riboflavin, and phosphorus in a more bioavailable form. Aged cheese, on the other hand, contains higher levels of vitamin K2, beneficial for bone and heart health, and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a compound with potential anti-inflammatory properties. However, cheese’s sodium content is significantly higher—Parmesan contains about 1,600 mg per 100 grams, compared to 100 mg in milk. For individuals monitoring sodium intake, this trade-off is crucial. Additionally, lactose-intolerant individuals may tolerate aged cheese better due to its lower lactose content, but its higher saturated fat levels (around 25 grams per 100 grams in Cheddar vs. 8 grams in whole milk) warrant moderation.

Practical Considerations for Consumption:

To balance calcium intake with other nutrients, consider a hybrid approach. Incorporate milk into beverages, cereals, or smoothies for a low-calorie, nutrient-dense calcium source. Reserve aged cheese for flavor enhancement in salads, soups, or as a garnish, limiting portions to 30–50 grams per serving. For children and adolescents, milk remains superior for overall nutrient intake, including protein and vitamin D, essential for growth. Adults, particularly postmenopausal women, may benefit from aged cheese’s calcium and vitamin K2 but should monitor sodium and fat intake. Pairing cheese with potassium-rich foods like spinach or bananas can help offset sodium’s effects.

The calcium advantage of aged cheese comes with trade-offs in sodium, fat, and other nutrients. Milk offers a more balanced profile but falls short in calcium density. The optimal choice depends on individual health goals, dietary restrictions, and nutrient priorities. For calcium alone, aged cheese wins; for a comprehensive nutrient package, milk takes the lead. Combining both in moderation ensures a harmonious intake of calcium and other essentials, tailored to specific needs.

Crunchy Breadsticks: A Perfect Pairing for Fruit and Cheese Platters?

You may want to see also

Health Implications: Effects of aged cheese and milk calcium on bone health and diet

Calcium is a cornerstone nutrient for bone health, but not all sources are created equal. Aged cheese, often celebrated for its rich flavor, contains more calcium per gram than milk due to the concentration process during aging. For instance, 100 grams of aged cheddar provides approximately 720 mg of calcium, while the same amount of whole milk offers around 120 mg. This disparity raises questions about the comparative benefits of aged cheese versus milk for bone health and dietary considerations.

From a dietary perspective, incorporating aged cheese as a calcium source requires mindful portion control. While it’s calcium-dense, aged cheese is also higher in calories, saturated fats, and sodium compared to milk. A 30-gram serving of aged Parmesan, for example, delivers about 330 mg of calcium but also contains 120 calories and 200 mg of sodium. In contrast, a 240-ml glass of milk provides 300 mg of calcium with only 150 calories and minimal sodium. For individuals monitoring calorie or sodium intake, milk may be the more balanced option, despite its lower calcium density.

Bone health, particularly in aging populations, hinges on consistent calcium intake and absorption. Aged cheese’s calcium is highly bioavailable, meaning it’s readily absorbed by the body. However, its high phosphorus content can interfere with calcium absorption if consumed in excess. Milk, on the other hand, offers a more balanced nutrient profile, including vitamin D and potassium, which enhance calcium utilization. For adults over 50, who require 1,200 mg of calcium daily, combining both sources—such as a glass of milk with a small serving of aged cheese—can optimize intake without overloading on less desirable components.

Practical tips for leveraging these calcium sources include pairing aged cheese with low-sodium, calcium-rich foods like leafy greens to mitigate its drawbacks. For example, a salad topped with 15 grams of grated aged cheese adds 165 mg of calcium without significantly increasing sodium. Milk can be incorporated into smoothies or oatmeal to boost calcium intake without adding saturated fats. Pregnant women, adolescents, and postmenopausal individuals, who have higher calcium needs (1,000–1,300 mg daily), may benefit from prioritizing milk for its overall nutrient profile, while using aged cheese as a flavorful, calcium-rich accent in meals.

Ultimately, the choice between aged cheese and milk for calcium depends on individual health goals and dietary constraints. Aged cheese offers concentrated calcium but requires moderation due to its calorie and sodium content. Milk provides a more holistic nutrient package but delivers less calcium per gram. By understanding these nuances, individuals can tailor their diets to support bone health effectively, whether by enjoying a slice of aged Gouda occasionally or opting for a daily glass of milk.

Cheesy Style: Embracing the Fun of Cheese-Themed Food Shirts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, aged cheese generally has more calcium per serving than milk due to its concentrated nutrient content.

Aged cheese has higher calcium levels because the aging process reduces moisture, concentrating the nutrients, including calcium.

A 1-ounce serving of aged cheese (like Parmesan) contains about 330 mg of calcium, while an 8-ounce glass of milk has around 300 mg.

The calcium in both aged cheese and milk is similarly absorbed, but cheese’s fat content may slightly enhance calcium absorption.

Yes, aged cheese is often a better calcium source for lactose-intolerant individuals because the aging process breaks down most of the lactose.