The question of whether all cheese contains wax is a common one, often arising from the visible coating on certain types of cheese, such as cheddar or Gouda. While it’s true that some cheeses are coated with wax to preserve freshness and prevent mold, not all cheeses contain or require this protective layer. Wax is primarily used for harder, longer-aging cheeses, whereas softer varieties like Brie or mozzarella are typically packaged in plastic or parchment. Understanding the role of wax in cheese production helps clarify why it’s not a universal ingredient, but rather a specific method for certain types of cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does all cheese contain wax? | No |

| Purpose of wax on cheese | Preserves moisture, prevents mold, protects during aging |

| Types of cheese commonly coated with wax | Cheddar, Gouda, Edam, Colby |

| Types of wax used | Food-grade paraffin, microcrystalline, carnauba, or beeswax |

| Is wax edible? | Generally not recommended, though non-toxic |

| Alternatives to wax coating | Vacuum sealing, plastic wrap, natural rinds |

| Wax removal before consumption | Recommended for most wax types |

| Health concerns | Minimal, but ingestion may cause digestive discomfort |

| Environmental impact | Some waxes are biodegradable, but paraffin is petroleum-based |

| Regulatory approval | Food-grade waxes are approved by FDA and similar agencies |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Natural Cheese Coatings: Some cheeses develop natural rinds, not wax, during aging

- Waxing Process: Wax is applied to preserve moisture and protect cheese from mold

- Types of Wax: Food-grade waxes like paraffin or beeswax are commonly used

- Wax-Free Cheeses: Fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta are never waxed

- Edible vs. Non-Edible: Most wax coatings are not meant to be eaten

Natural Cheese Coatings: Some cheeses develop natural rinds, not wax, during aging

Not all cheeses rely on wax for protection during aging. Many varieties develop natural rinds, a complex and fascinating process that contributes to their unique flavors and textures. This phenomenon challenges the common assumption that wax is a universal cheese coating, revealing a more nuanced world of cheesemaking.

Unlike wax, which is an external application, natural rinds form organically as the cheese matures. This process involves the growth of specific molds, bacteria, and yeasts on the cheese's surface, creating a protective barrier that influences the cheese's character. For instance, the iconic orange rind of a Mimolette is the result of Penicillium candidum mold, while the wrinkled, grey exterior of a Saint-Nectaire is a product of mixed mold and yeast cultures.

These natural rinds are not merely decorative; they play a crucial role in the cheese's development. They regulate moisture loss, allowing the cheese to age without drying out completely. The microorganisms within the rind also contribute to the cheese's flavor profile, adding earthy, nutty, or even pungent notes.

Understanding natural rinds allows cheese enthusiasts to appreciate the artistry and science behind cheesemaking. It encourages exploration beyond the familiar wax-coated varieties, opening doors to a diverse range of flavors and textures. When selecting cheese, consider the rind as a clue to its character. A thick, hard rind often indicates a longer aging process and a stronger flavor, while a thin, bloomy rind suggests a softer, milder cheese.

For those interested in experiencing the magic of natural rinds firsthand, consider seeking out cheeses like Camembert, Brie, or Reblochon. These cheeses showcase the beauty of this natural aging process, offering a delightful sensory experience that goes beyond the wax-coated norm. Remember, the rind is not always meant to be eaten, so taste and texture preferences should guide your consumption.

Gouda vs. Gruyere: Unraveling the Distinct Flavors and Textures

You may want to see also

Waxing Process: Wax is applied to preserve moisture and protect cheese from mold

Not all cheeses are created equal, and the same goes for their preservation methods. While some cheeses are left to age naturally, others undergo a waxing process to extend their shelf life. This technique involves coating the cheese in a layer of wax, typically made from paraffin or beeswax, to create a protective barrier. The primary purpose of this process is twofold: to preserve moisture within the cheese and to prevent mold growth, ensuring the cheese remains edible and flavorful for an extended period.

The waxing process is a delicate art, requiring precision and attention to detail. First, the cheese is carefully cleaned and dried to remove any surface moisture. Then, the wax is melted and applied evenly, often by hand or using specialized equipment, to create a seamless coating. The thickness of the wax layer is crucial; too thin, and it may not provide adequate protection, while too thick can alter the cheese's texture and flavor. A typical wax coating ranges from 1-3 mm, depending on the cheese variety and desired aging time. For instance, a young cheddar might receive a thinner coating, while an aged Gouda could benefit from a more substantial wax layer.

One of the key advantages of waxing is its ability to regulate moisture content. Cheese is a living, breathing product, and its moisture levels can significantly impact its quality. Wax acts as a semi-permeable membrane, allowing the cheese to breathe while minimizing moisture loss. This is particularly beneficial for harder cheeses, which can become dry and crumbly if not properly protected. By maintaining the right moisture balance, waxed cheeses can develop complex flavors and textures over time, making them a favorite among cheese enthusiasts.

However, the waxing process is not without its challenges. One concern is the potential for mold growth beneath the wax layer. To mitigate this, cheesemakers often treat the cheese with a mold-inhibiting solution before waxing. Additionally, the type of wax used is essential; food-grade paraffin or beeswax is preferred for its safety and ability to adhere well to the cheese. It's worth noting that while wax provides protection, it doesn't make the cheese immune to spoilage. Proper storage conditions, such as cool temperatures and adequate ventilation, are still necessary to ensure the cheese's longevity.

In the world of cheese, waxing is a valuable technique that allows for the preservation and enjoyment of a wide variety of cheeses. It enables cheesemakers to control the aging process, ensuring consistent quality and flavor. For consumers, waxed cheeses offer a convenient and long-lasting option, perfect for those who want to savor their favorite varieties over an extended period. Whether it's a classic waxed Cheddar or an experimental blue cheese, the waxing process plays a crucial role in delivering delicious, high-quality cheese to tables worldwide. This method is a testament to the ingenuity of cheesemakers, combining tradition and innovation to create a truly remarkable culinary experience.

String Cheese vs. Regular Cheese: Unraveling the Melty Differences

You may want to see also

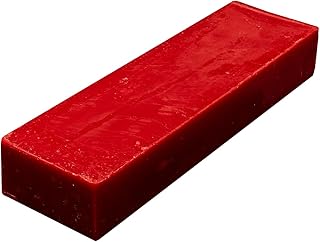

Types of Wax: Food-grade waxes like paraffin or beeswax are commonly used

Not all cheeses are created equal, especially when it comes to their outer coatings. While some cheeses boast a natural rind formed during aging, others are deliberately coated with wax to preserve moisture and flavor. Food-grade waxes like paraffin or beeswax are the stars here, serving as protective barriers that extend shelf life without compromising quality. Paraffin wax, derived from petroleum, is odorless, tasteless, and highly effective at sealing out air and mold. Beeswax, a natural alternative, offers similar benefits with the added allure of a subtle, honey-like aroma. Both are safe for consumption and approved by food safety regulations, making them ideal for cheeses ranging from cheddars to Goudas.

Choosing the right wax for cheese coating involves more than just picking between paraffin and beeswax. Paraffin wax is often preferred for its affordability and ease of application—simply melt it in a double boiler and brush or dip the cheese until evenly coated. Beeswax, while pricier, is favored by artisanal cheesemakers for its sustainability and natural appeal. However, it requires a higher melting point and can be trickier to work with. For home cheesemakers, a blend of 80% paraffin and 20% beeswax strikes a balance, offering both ease and a touch of natural charm. Always ensure the wax is food-grade and free from additives to avoid contamination.

The application process is as crucial as the wax itself. Start by ensuring the cheese is dry and at room temperature to prevent moisture from becoming trapped underneath. Heat the wax to 160°F–180°F (71°C–82°C) for optimal consistency—too hot, and it can scorch; too cold, and it won’t adhere properly. Use a brush or dipping method, applying thin, even layers to avoid cracking. Allow each layer to cool before adding the next, typically 2–3 coats for full coverage. For aged cheeses, wax coating can extend freshness by months, but remember: wax is a preservative, not a miracle worker. Proper storage in a cool, dark place remains essential.

While wax-coated cheeses are safe to eat, the wax itself is not meant for consumption. Always remove the wax layer before serving, using a knife or peeler to carefully strip it away. For those concerned about waste, both paraffin and beeswax can be reused. Simply scrape off excess wax, melt it down, and strain through a fine mesh to remove impurities. Reusing wax not only reduces costs but also aligns with sustainable practices, a growing priority in modern food production. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or enthusiast, understanding these wax types and techniques ensures your cheese remains a masterpiece from rind to core.

Why Do I Taste Cheese in My Mouth? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Wax-Free Cheeses: Fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta are never waxed

Not all cheeses are created equal, especially when it comes to wax. While aged cheeses like Cheddar or Gouda often rely on wax coatings for preservation, fresh cheeses like mozzarella and ricotta are never waxed. This distinction is rooted in their production process and intended use. Fresh cheeses are made by curdling milk and draining the whey, resulting in a soft, moist texture that doesn’t require additional protection. Wax, typically used to prevent mold and extend shelf life, would interfere with their delicate flavor and consistency. For instance, mozzarella’s stretchy, milky quality and ricotta’s crumbly, creamy nature are preserved precisely because they remain wax-free.

Consider the culinary implications of this difference. Fresh, unwaxed cheeses are ideal for dishes where texture and flavor take center stage. Mozzarella melts into gooey perfection on a pizza, while ricotta adds lightness to lasagna or spreads effortlessly on toast. Waxed cheeses, on the other hand, are better suited for aging and slicing, their coatings acting as a barrier against external elements. When selecting cheese for a recipe, understanding this distinction ensures the right choice. For example, using waxed cheese in a caprese salad would be a mismatch—its texture and taste would clash with the freshness of tomatoes and basil.

From a preservation standpoint, the absence of wax in fresh cheeses means they have a shorter shelf life. Mozzarella, for instance, should be consumed within a week of purchase, while ricotta lasts about two weeks when refrigerated. To maximize freshness, store these cheeses in airtight containers and avoid exposing them to air, which accelerates spoilage. Unlike waxed cheeses, which can last months, fresh cheeses demand prompt use but reward with unparalleled taste and texture. This trade-off highlights the purpose-driven nature of cheese-making techniques.

For those seeking practical tips, here’s a quick guide: when buying fresh cheeses, opt for those packaged in water or brine, as this preserves moisture. Drain excess liquid before use, but avoid rinsing, as this dilutes flavor. If you’re making fresh cheese at home, use pasteurized milk and food-grade rennet for safety. Remember, the absence of wax in these cheeses is a feature, not a flaw—it’s what makes them perfect for immediate enjoyment. By embracing their natural state, you’ll elevate dishes with authenticity and freshness.

In summary, the wax-free nature of fresh cheeses like mozzarella and ricotta is a deliberate choice, preserving their unique qualities. Understanding this distinction empowers better culinary decisions, from recipe selection to storage. While waxed cheeses have their place, fresh cheeses shine in their simplicity, offering a pure, unaltered experience. Next time you savor a creamy ricotta or stretchy mozzarella, appreciate the craftsmanship behind their wax-free perfection.

Mastering Cheese Wedge Cuts for Perfect Charcuterie Board Presentation

You may want to see also

Edible vs. Non-Edible: Most wax coatings are not meant to be eaten

Cheese wax serves a practical purpose: it preserves moisture, prevents mold, and extends shelf life. But not all wax is created equal. Most cheese wax is non-edible, formulated with paraffin or petroleum-based compounds designed for durability, not digestion. While these waxes effectively protect the cheese, they can cause digestive discomfort if consumed. Always remove non-edible wax before eating, as it’s not meant to be part of your snack.

Edible wax coatings, though less common, do exist. Derived from natural sources like carnauba, beeswax, or shellac, these waxes are safe to consume in small quantities. They’re often used on cheeses like Edam or Gouda for both protection and aesthetic appeal. However, even edible wax isn’t exactly a culinary delight—it’s bland, chewy, and adds little to the cheese-eating experience. If you encounter a wax coating, assume it’s non-edible unless explicitly labeled otherwise.

Distinguishing between edible and non-edible wax isn’t always straightforward. Edible waxes are typically labeled as "food-grade" or "consumable," but many cheeses lack clear markings. A practical tip: if the wax feels hard, brittle, and synthetic, it’s likely non-edible. Softer, more pliable waxes might be edible, but err on the side of caution. When in doubt, peel it off—better safe than sorry.

For those who enjoy DIY cheese projects, choosing the right wax matters. If you’re aging cheese at home, opt for food-grade wax specifically designed for cheese preservation. Avoid craft or candle wax, which can contain harmful additives. Apply the wax in thin, even layers, ensuring full coverage to protect your cheese. Remember, the goal is preservation, not consumption—keep the wax off your plate.

In summary, while wax is a common cheese coating, most varieties are non-edible and should be removed before eating. Edible wax exists but is rare and unappetizing. Always prioritize safety by checking labels or peeling off the wax entirely. Whether you’re a cheese enthusiast or a home cheesemaker, understanding the difference between edible and non-edible wax ensures a better, safer cheese experience.

The Amazing Race's Iconic Cheese Wheel Challenge: Which Season?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all cheese contains wax. Wax is primarily used as a coating on certain types of cheese to preserve moisture and protect against mold.

Cheeses like Cheddar, Gouda, and Edam are commonly coated in wax to extend their shelf life and maintain their texture.

While the wax used on cheese is food-grade and non-toxic, it is not intended to be eaten and should be removed before consuming the cheese.

Wax is used on harder cheeses that benefit from protection against air and moisture loss, whereas softer cheeses are often wrapped in paper or plastic instead.

It’s not recommended to eat the wax, as it can be difficult to digest and is not meant for consumption. Always remove the wax before eating the cheese.