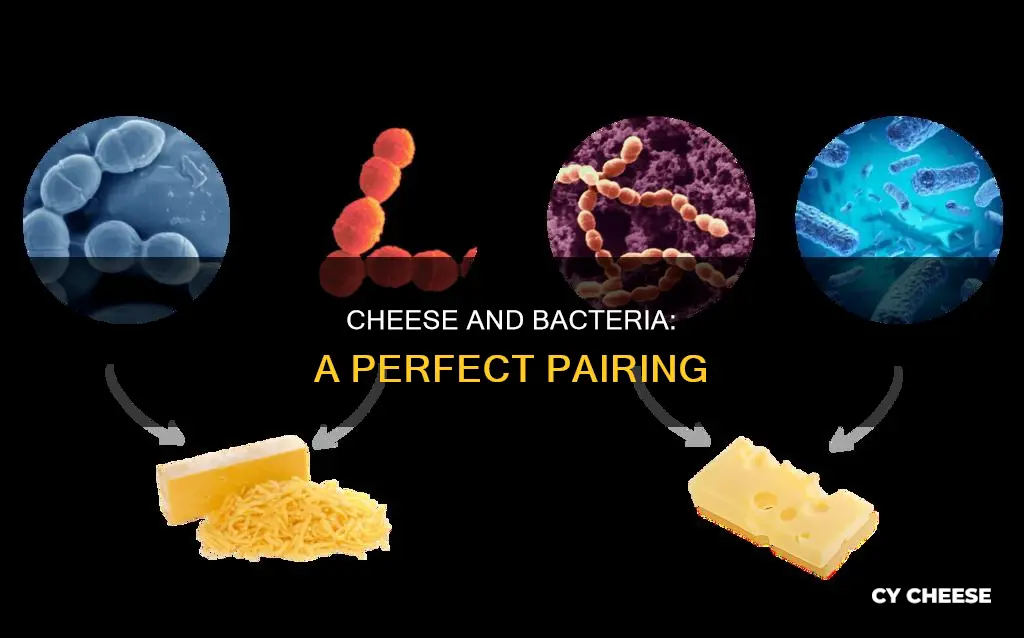

Cheese is a beloved food that has been consumed since the late Stone Age. It is made through a process of removing water from milk, which concentrates the milk's protein, fat, and other nutrients, and increases its shelf life. The four main ingredients required to make cheese are milk, salt, rennet (or another coagulant), and microbes. The addition of microbes, such as bacteria, yeasts, and moulds, is essential to the cheesemaking process and plays a significant role in shaping the flavour and texture of the final product. Bacteria break down milk proteins into smaller pieces, releasing enzymes that contribute to the distinct flavours and aromas associated with different types of cheese. The variety of microbes used in cheesemaking results in the diverse range of cheeses available today, each with its own unique characteristics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Microorganisms found in cheese | Bacteria, yeasts, and molds |

| Number of microbial species in a single cheese type | More than 100 |

| Types of bacteria | Lactic acid bacteria, Non-starter lactic acid bacteria, Brevibacter linens, Propionobacter shermanii, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Lactococcus lactis ssp lactis biovar. diacetylactis, Lactobacillus helveticus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subspecies bulgaricus, Thermoduric species of Bacillus, Clostridium, Microbacterium, Micrococcus, Streptococcus |

| Types of molds | Blue, White, Penicillium spp., Penicillium roqueforti, Penicillium camemberti, Penicillium candidum, Cladosporium cladosporioides, C. herbarum, P. glabrum, Phoma species |

| Types of yeasts | Geotrichum candidum, Pichia spp., Candida spp. |

| Role of microbes in cheese | Flavoring, Texturing, Ripening, Preservation |

| Microbial growth factors | Moisture content, Water activity, Redox potential, Aerobic or anaerobic conditions, pH, Acidity, Salt level |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Bacteria and fungi can influence the flavour and texture of cheese

Bacteria and fungi play a significant role in shaping the flavour and texture of cheese. Cheese is a food that contains extraordinarily high numbers of living, metabolising microbes. The broad groups of cheese-making microbes include several varieties of bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi (moulds).

The milk of cows, goats, or sheep contains some microbes, but many more are picked up during the milking and cheesemaking process. For example, soil bacteria lurking in a stable's straw bedding might attach itself to the teats of a cow and end up in the milk pail. The basic principles of cheese-making include the removal of water from milk, the breakdown of milk proteins (caseins) and fat, the addition of salt, and an optional ripening period. Each of these steps influences the final texture, aroma, and flavour.

Cheese is made with "starter cultures" of beneficial bacteria, which are added to freshly formed curds to induce the fermentation process. The main reaction taking place here is the conversion of lactose to lactic acid, acidifying the milk. Examples of these starter cultures include Lactococci, Streptococci, and Lactobacilli. The starter culture changes the cheese microenvironment, affecting factors such as pH, redox potential, and levels of organic acids. As some of the lactic acid bacteria within the starter culture begin to die, they release enzymes that further break down milk proteins, and these enzymes can also impart particular flavours and textures.

During the ripening process, a second wave of diverse bacteria and fungi (secondary microbiota) grow within the cheese and on its surface, sometimes forming a rind. The specific bacteria and fungi that grow on the cheese depend on the cheese's environment, such as its salt concentration and nutrients present. Some bacteria that grow on cheese, such as Brevibacterium linens, are responsible for foot odour, which explains the smell of many surface-ripened cheeses. B. linens also adds characteristic notes to the odour of sweat.

The two main types of mould found in cheese are blue and white. While some moulds are added by cheesemakers, many grow naturally on the surfaces of cheese. Penicillium camemberti is a popular mould species responsible for the white surface of cheeses like Camembert and Brie, and its metabolism produces characteristic aromas and textures. Penicillium roqueforti is a common blue mould added to cheese, and Geotrichum candidum is a yeast that exhibits mould-like tendencies and is responsible for the "brainy" appearance of some cheeses.

Cheese for Diabetics: Best Options and Recommendations

You may want to see also

Microbes in cheese include bacteria, yeasts, and moulds

The creation of cheese is a microbial process that depends on metabolic enzymes to break down complex substances into simpler ones. Microbes in cheese include bacteria, yeasts, and moulds.

Bacteria are the first microbial settlers in milk. The most common types of bacteria used in cheese are lactic acid bacteria (LABs). These bacteria feed on lactose, the sugar in the milk, and produce lactic acid, which causes the milk to sour. This process of converting lactose to lactic acid is called fermentation. As the milk becomes more acidic, it becomes inhospitable for many microbes, including potential pathogens. However, certain yeasts, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker's yeast), can survive in this environment and feed on the lactic acid, neutralizing the acidity and allowing other bacteria to join.

The bacteria, yeasts, and moulds in cheese can be added intentionally by the cheesemaker or occur naturally in the milk or environment. For example, moulds like Penicillium camemberti (formerly known as Penicillium candidum) are added by cheesemakers and are responsible for the white surface on cheeses like Camembert and Brie. On the other hand, moulds that naturally grow on the surfaces of cheese during ageing can contribute to the cheese's unique flavour.

The interaction between bacteria, yeasts, and moulds creates an ecosystem within the cheese, resulting in the distinctive characteristics of each cheese variety. The microbes break down milk fats and proteins, giving cheese its creamy texture and flavour. They also produce pigments that affect the colour of the cheese.

Cheese is a unique food due to the extraordinarily high numbers of living, metabolizing microbes it contains. A single gram of fully ripened cheese rind may contain approximately 10 billion bacteria, yeasts, and other fungi.

Vegan Cheeses: The Ultimate Guide to Dairy-Free Deliciousness

You may want to see also

Bacteria break down milk proteins into flavour compounds

Bacteria play a crucial role in the breakdown of milk proteins into flavour compounds, a process that is essential for creating the diverse flavours found in different types of cheese. This process involves various biochemical pathways and microbial activities that transform the milk proteins into an array of flavourful compounds.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are a group of bacteria that are particularly important in this process. During cheese fermentation, LAB break down milk proteins into peptides and free amino acids, which serve as a source of nutrients for the bacteria. This proteolysis process is initiated by an extracellular proteinase produced by the LAB. The degradation of milk proteins leads to the formation of flavour compounds, including aldehydes, alcohols, carboxylic acids, and esters. These compounds contribute to the unique flavours associated with different types of cheese.

Additionally, the starter cultures used in cheese fermentation play a significant role in flavour development. These cultures, which include microbes such as Lactobacillus helveticus, Lactococcus lactis, and Streptococcus thermophilus, influence the cheese microenvironment by affecting factors such as pH and organic acid levels. As the starter cultures begin to die off, they release enzymes that further break down milk proteins, particularly casein. This breakdown results in the production of additional flavour compounds that enhance the overall flavour profile of the cheese.

The presence of non-starter lactic acid bacteria (NSLAB) also contributes to flavour development. NSLAB are naturally present in the milk or introduced during cheesemaking. As the cheese ages, the population of NSLAB increases, and they continue to break down milk proteins, influencing the cheese's flavour and texture.

Furthermore, specific bacteria, such as Brevibacter linens, are known for their ability to break down proteins into potent odour compounds. These compounds contribute to the strong aromas associated with certain cheeses, ranging from oniony and garlicky to fishy and sweaty notes. Another example is Propionibacter shermanii, which can digest acetic acid and convert it into propionic acid and carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide creates the characteristic "holes" in cheeses like Emmental, while the propionic acid contributes to their sharp and complex bouquet.

In addition to bacteria, moulds also play a role in breaking down milk proteins and developing flavours in cheese. Blue and white moulds are commonly added to cheeses, with Penicillium being the most popular mould species. These moulds produce enzymes that break down milk proteins, resulting in the formation of flavour compounds with distinct garlicky, earthy, or mushroom-like notes.

The Best Ways to Store Cheese at Home

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Bacteria are added to cheese intentionally or picked up during cheesemaking

Bacteria play a crucial role in the cheesemaking process, and they can be introduced in two main ways: either intentionally added by the cheesemaker or naturally picked up during the various stages of cheesemaking.

Intentional Addition of Bacteria

Cheesemakers intentionally add specific bacteria to milk or curds to kickstart the fermentation process and develop the desired flavour, texture, and aroma profiles. These bacteria are known as "starter cultures" and include lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and non-lactic acid bacteria. Starter cultures affect the cheese microenvironment by influencing factors such as pH, redox potential, and levels of organic acids. As these bacteria begin to die off, they release enzymes that break down milk proteins, providing food for subsequent generations of bacteria.

Natural Acquisition of Bacteria

During the cheesemaking process, bacteria are naturally acquired from various sources. Some bacteria are native to the milk itself, while others are introduced during the milking and cheesemaking processes. The ambient environment also plays a role, as bacteria can drift in from the surrounding area and even from the cheesemakers themselves. This natural acquisition of bacteria contributes to the unique "terroir" of the cheese, with each cheese taking on a distinct microbial profile that influences its characteristics.

Examples of Intentionally Added Bacteria

Commonly added bacteria include Lactobacillus helveticus, which imparts a sweet flavour to cheeses like aged Gouda, and Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis, which contribute to the eye formation in Gouda and Swiss cheeses. Brevibacterium linens, found in Limburger cheese, is known for its role in producing strong odour compounds, resulting in characteristic aromas.

Examples of Naturally Acquired Bacteria

On the other hand, Penicillium camemberti (formerly known as Penicillium candidum) is a mould species that naturally develops on the surfaces of cheeses like Camembert and Brie. It is responsible for the white appearance and contributes to the characteristic aromas and textures associated with these cheeses. Another example is Halomonas, a marine microbe that may find its way into cheese via the sea salt used by cheesemakers.

Cheeses to Choose: Healthy Options for Your Plate

You may want to see also

Bacteria can cause cheese spoilage

Cheese provides an ideal environment for the growth of microorganisms, including bacteria, yeasts, and molds. This can lead to spoilage and contamination, especially in cheeses made from unpasteurized milk or those with short ripening periods. Proper hygiene practices and preventive measures are crucial to avoid product contamination and the growth of pathogenic organisms, such as Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella spp.

Surface bacteria, including Pseudomonas spp. and Flavobacterium spp., can proliferate on the surface layers of cheese, leading to rancid and off-flavors. Additionally, molds, which are a type of fungus, can cause significant spoilage in cheese. They can grow in low-temperature, low-oxygen conditions and produce off-flavors, discoloration, and bitter peptides. Molds, such as Penicillium roqueforti and G. candidum, are often added to cheese intentionally to create specific flavors and textures, but they can also cause spoilage if not controlled properly.

Some bacteria, like Brevibacterium linens or "smear" bacteria, are encouraged to grow on the surface of "washed-rind" cheeses through continual washing or wiping. While these bacteria contribute to the desired flavor and appearance, they can also produce strong odor compounds that some may find unpleasant.

To prevent spoilage, it is essential to follow proper cheese-making practices, including the use of starter cultures and controlling the growth environment. Starter cultures, such as Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB), are intentionally added to milk to promote fermentation and inhibit pathogens. However, as cheese ages, Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria (NSLAB) can increase, and their roles in cheese flavor development are still being understood. Overall, the balance of microorganisms in cheese dictates its fate, and spoilage can occur when this balance is disrupted.

Ultimate Nacho Cheese: The Best Melting Cheeses

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The main types of microbes found in cheese are bacteria, yeasts, and moulds.

Microbes are responsible for the flavour and texture of the final cheese. For example, lactic acid bacteria produce acetoin and diacetyl, which can also be found in butter and give cheeses a rich, buttery taste.

Cheesemakers use "starter cultures" of beneficial bacteria to help the cheese along. Salt is also used to inhibit the growth of undesirable bacteria.