Cheese is a beloved dairy product enjoyed worldwide, but its production involves a fascinating process that often goes unnoticed. One intriguing aspect is the role of cultures in cheese-making. These cultures, also known as starter cultures, are a crucial component, consisting of specific strains of bacteria and sometimes molds, which are intentionally added to milk to initiate the fermentation process. This process not only contributes to the unique flavors and textures of different cheese varieties but also plays a significant role in determining the overall quality and character of the final product. Understanding the presence and function of these cultures is essential for anyone curious about the art and science behind cheese production.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does Cheese Contain Cultures? | Yes, most cheeses contain live and active cultures. |

| Types of Cultures | Lactic acid bacteria (e.g., Lactococcus, Lactobacillus), Propionibacterium (in Swiss cheese), Penicillium molds (in blue cheese), and others. |

| Role of Cultures | Ferment lactose into lactic acid, contribute to flavor, texture, and aroma development, inhibit harmful bacteria, and aid in preservation. |

| Live Cultures in Cheese | Present in fresh, unpasteurized, or aged cheeses (e.g., cheddar, Gouda, Brie, feta). |

| No Live Cultures | Found in pasteurized processed cheeses or those treated with heat or preservatives. |

| Health Benefits | Probiotic properties (in cheeses with live cultures), support gut health, and enhance nutrient absorption. |

| Labeling | Look for terms like "live and active cultures," "contains live cultures," or "probiotic" on packaging. |

| Examples of Cultured Cheeses | Cheddar, Gouda, Brie, Camembert, Blue Cheese, Feta, Mozzarella (when made with raw milk). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Cultures in Cheese: Lactic acid bacteria, propionibacteria, and molds are common cultures in cheese

- Role of Cultures in Cheese Making: Cultures ferment lactose, produce flavor, and contribute to texture and preservation

- Live Cultures in Cheese: Some cheeses contain live, active cultures, offering potential probiotic benefits

- Cultures in Aged vs. Fresh Cheese: Aged cheeses have more developed cultures, while fresh cheeses have fewer

- Cheese Without Cultures: Processed cheeses often lack live cultures due to pasteurization and additives

Types of Cultures in Cheese: Lactic acid bacteria, propionibacteria, and molds are common cultures in cheese

Cheese is a living food, teeming with microscopic organisms that shape its flavor, texture, and aroma. Among these, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are the unsung heroes of the cheese world. These bacteria, including *Lactococcus* and *Streptococcus* species, are the first to colonize milk during cheesemaking. They convert lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, lowering the pH and creating an environment hostile to harmful bacteria. This process not only preserves the milk but also contributes to the tangy, sharp notes found in cheeses like cheddar and feta. For home cheesemakers, using a starter culture rich in LAB is essential—typically dosed at 1-2% of milk volume—to ensure consistent results. Without these bacteria, cheese would lack its characteristic acidity and complexity.

While lactic acid bacteria dominate the early stages of cheesemaking, propionibacteria play a unique role in specific varieties, most notably Swiss cheese. These slow-growing bacteria produce carbon dioxide gas and propionic acid, responsible for the distinctive eye formation and nutty flavor in Emmental and Gruyère. Propionibacteria require a longer aging period—often 3-6 months—to fully develop their effects. Cheesemakers must carefully control temperature (around 20-24°C) and humidity to encourage their growth. Interestingly, these bacteria are also used in vitamin B12 production, highlighting their versatility beyond the dairy industry. Their contribution to cheese is subtle yet transformative, turning a simple block of curd into a masterpiece of texture and taste.

Molds, often feared in everyday life, are celebrated in the cheese world for their ability to create bold flavors and striking appearances. Surface-ripened cheeses like Brie and Camembert rely on *Penicillium camemberti*, which forms a velvety white rind and imparts earthy, mushroom-like notes. Blue cheeses, such as Roquefort and Stilton, are veined with *Penicillium roqueforti*, delivering a pungent, spicy kick. These molds require specific conditions—high humidity and controlled airflow—to thrive. For home enthusiasts, introducing mold spores via spraying or dipping is a delicate process, as overuse can lead to overpowering flavors. Molds not only enhance taste but also act as natural preservatives, extending the cheese’s shelf life.

Understanding the interplay between these cultures is key to appreciating cheese’s diversity. Lactic acid bacteria lay the foundation, propionibacteria add depth, and molds bring character. Each culture’s role is distinct, yet they work in harmony to create a symphony of flavors. For instance, in a semi-hard cheese like Gouda, LAB provide acidity, while a secondary culture of *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* can add complexity. This layered approach is why cheesemaking is both a science and an art. By mastering these cultures, both professionals and hobbyists can craft cheeses that tell a story through every bite.

Master Smoking Cheese in Your Char Broil Electric Smoker: A Guide

You may want to see also

Role of Cultures in Cheese Making: Cultures ferment lactose, produce flavor, and contribute to texture and preservation

Cheese, a beloved staple in diets worldwide, owes its diverse flavors, textures, and longevity to the microscopic heroes of fermentation: cultures. These bacteria and molds are not mere additives but the architects of cheese transformation, turning simple milk into a complex, edible masterpiece. Without them, cheese as we know it would not exist.

Consider the fermentation process, the cornerstone of cheese making. Cultures, primarily lactic acid bacteria (LAB), consume lactose (milk sugar) and convert it into lactic acid. This acidification is critical for several reasons. First, it lowers the pH of the milk, causing it to curdle and separate into curds and whey. Second, it creates an environment hostile to harmful bacteria, acting as a natural preservative. For instance, in cheddar production, *Lactococcus lactis* is commonly used at a dosage of 0.02–0.05% of milk volume to ensure consistent acidification. This step is non-negotiable—skip it, and you’ll end up with spoiled milk, not cheese.

Flavor development is another area where cultures shine. As they metabolize lactose, they produce byproducts like diacetyl, which gives butter-like notes to cheeses such as Gouda, and acetic acid, contributing to the tangy profile of Swiss cheese. Some cultures, like *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, are responsible for the distinctive eye formation and nutty flavor in Emmental. The choice of culture strain and its activity level dictate the cheese’s final taste profile. For home cheesemakers, experimenting with different cultures—such as mesophilic vs. thermophilic strains—can yield dramatically different results, even with the same milk source.

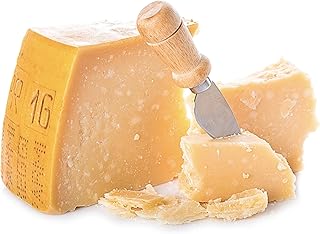

Texture, too, is a cultural affair. During aging, cultures continue to break down proteins and fats, influencing the cheese’s firmness, creaminess, or crumbly nature. In blue cheeses like Roquefort, *Penicillium roqueforti* molds penetrate the curd, creating veins and a creamy interior. Meanwhile, in aged cheeses like Parmesan, cultures contribute to a granular, crystalline texture by slowly hydrolyzing proteins over months or even years. Controlling temperature and humidity during aging amplifies these effects—a cooler environment slows culture activity, resulting in a milder flavor and firmer texture.

Finally, cultures act as guardians of cheese preservation. By producing acids, alcohols, and bacteriocins (natural antibiotics), they inhibit the growth of spoilage organisms. This is why properly cultured cheeses can age for years without spoiling, developing deeper flavors and complexities over time. For example, the surface molds in Brie (*Penicillium camemberti*) not only contribute to its bloomy rind but also protect the cheese from contamination. Without these protective cultures, cheese would be far more perishable and less safe to consume.

In essence, cultures are the unsung heroes of cheese making, driving fermentation, flavor, texture, and preservation. Whether you’re a professional cheesemaker or a curious home enthusiast, understanding their role allows you to manipulate these variables to craft cheese that’s not just edible, but extraordinary. Choose your cultures wisely, control their environment, and let them work their magic—the result will be a testament to the power of microbiology in the kitchen.

Processed Cheese vs. Regular Cheese: Understanding the Key Differences

You may want to see also

Live Cultures in Cheese: Some cheeses contain live, active cultures, offering potential probiotic benefits

Cheese, a beloved staple in diets worldwide, often harbors more than just flavor—it can be a source of live, active cultures. These microorganisms, primarily lactic acid bacteria, are not only essential for the fermentation process but also survive in certain cheeses, offering potential health benefits. Unlike pasteurized cheeses, which undergo heat treatment that kills bacteria, raw or unpasteurized cheeses retain these live cultures. Examples include cheddar, Gouda, and some types of blue cheese, where the cultures remain active, contributing to both texture and potential probiotic effects.

To harness the probiotic benefits of live cultures in cheese, consider incorporating raw milk varieties into your diet. A daily serving of 30–50 grams (roughly 1–1.75 ounces) of cheese like Gruyère or fresh goat cheese can provide a meaningful dose of beneficial bacteria. Pairing these cheeses with prebiotic-rich foods, such as garlic or onions, can enhance their effectiveness by nourishing the live cultures in your gut. However, be mindful of portion sizes, as cheese is also high in saturated fats and sodium.

Not all cheeses are created equal when it comes to live cultures. Aged cheeses, such as Parmesan or Pecorino, undergo lengthy maturation processes that often eliminate active bacteria. Conversely, softer, fresher cheeses like Brie or feta are more likely to retain live cultures due to shorter aging times. When shopping, look for labels indicating "raw milk" or "contains live cultures" to ensure you’re selecting a probiotic-rich option.

For those with lactose intolerance, live cultures in cheese can be a game-changer. During fermentation, bacteria break down lactose into lactic acid, making certain cheeses easier to digest. Hard cheeses like Swiss or aged cheddar typically contain minimal lactose, while the live cultures in softer varieties can further aid digestion. Start with small portions to assess tolerance and gradually increase intake as needed.

Incorporating live-culture cheeses into your diet requires balance. While their probiotic potential is promising, they are not a substitute for dedicated probiotic supplements, especially for addressing specific gut health issues. Consult a healthcare provider if you have underlying conditions or are pregnant, as raw milk cheeses carry a slight risk of foodborne illness. Enjoy these cheeses as part of a varied diet to maximize their benefits while minimizing potential drawbacks.

Unusual Tradition: The Surprising Practice of Throwing Cheese at Children

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cultures in Aged vs. Fresh Cheese: Aged cheeses have more developed cultures, while fresh cheeses have fewer

Cheese is a living food, teeming with microorganisms that contribute to its flavor, texture, and aroma. These microorganisms, known as cultures, play a pivotal role in the cheese-making process, particularly in the distinction between aged and fresh cheeses. Aged cheeses, such as Cheddar, Parmesan, and Gouda, undergo a prolonged maturation period during which cultures continue to develop, breaking down proteins and fats to create complex flavors. In contrast, fresh cheeses like mozzarella, ricotta, and chèvre are consumed shortly after production, leaving little time for cultures to evolve. This fundamental difference in culturing time results in distinct sensory experiences, with aged cheeses offering depth and intensity, while fresh cheeses provide a milder, more delicate profile.

To understand the disparity, consider the culturing process as a culinary symphony. In aged cheeses, the cultures are given ample time to harmonize, creating layers of flavor that unfold with each bite. For instance, a 2-year-old Cheddar may contain cultures that have transformed lactose into lactic acid, contributing to its tangy sharpness. Conversely, fresh cheeses are akin to a brief musical prelude—quick, light, and focused on preserving the milk’s natural freshness. A batch of ricotta, aged for mere hours, retains minimal cultural activity, resulting in a creamy, subtly sweet texture. This contrast highlights the intentionality behind cheese aging: the longer the cultures work, the more pronounced their impact.

From a practical standpoint, the culturing difference affects not only taste but also storage and usage. Aged cheeses, with their robust cultural development, often have a longer shelf life due to the preservation effects of acidification and fermentation. For example, a wheel of aged Gruyère can last up to 6 months when properly stored, whereas fresh goat cheese should be consumed within 1–2 weeks. When cooking, this distinction matters: aged cheeses like Pecorino Romano are ideal for grating over pasta due to their concentrated flavors, while fresh cheeses like burrata shine in salads or as a standalone appetizer, where their mildness complements other ingredients.

For home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, understanding the role of cultures in aging can elevate the craft. When aging cheese at home, maintain a consistent environment—ideally a cool, humid space (50–55°F with 85% humidity)—to encourage gradual cultural development. Fresh cheeses, on the other hand, require minimal intervention; focus on using high-quality milk and precise coagulation techniques to preserve their simplicity. Experimenting with culturing times, even in small batches, can reveal how subtle changes yield dramatically different results. For instance, aging a homemade Camembert for 3 weeks versus 6 weeks will showcase how cultures transform its texture from soft to creamy and its flavor from mild to earthy.

In essence, the culturing divide between aged and fresh cheeses is a testament to the art and science of cheesemaking. By appreciating how time and microorganisms interact, one can better select, store, and savor cheese. Whether you’re pairing a 10-year-old Gouda with a glass of port or spreading fresh chèvre on crusty bread, the cultures behind each cheese tell a story—one of patience, precision, and the transformative power of fermentation.

Converting 30 Grams of Cheese to Tablespoons: A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Cheese Without Cultures: Processed cheeses often lack live cultures due to pasteurization and additives

Processed cheeses, often found in individually wrapped slices or jars, typically lack live cultures due to the methods used in their production. Unlike traditional cheeses that rely on bacterial cultures for fermentation and flavor development, processed varieties undergo pasteurization at high temperatures, which eliminates any live microorganisms. Additionally, the inclusion of additives like emulsifiers and stabilizers further ensures a uniform texture and extended shelf life, but at the cost of the microbial activity that defines natural cheeses. This transformation from a living, breathing food to a stable, long-lasting product raises questions about the trade-offs between convenience and nutritional complexity.

Consider the process of making processed cheese: natural cheeses are shredded, mixed with water, emulsifiers (e.g., sodium phosphate), and melting salts, then heated to create a homogeneous blend. This method not only destroys live cultures but also alters the cheese’s nutritional profile. For instance, while natural cheddar contains probiotics like *Lactobacillus* and *Bifidobacterium*, processed cheddar lacks these beneficial bacteria. For those seeking the health benefits of live cultures, such as improved gut health, processed cheeses fall short. Instead, they cater to consumers prioritizing consistency, affordability, and longevity in their food choices.

From a practical standpoint, identifying processed cheeses without live cultures is straightforward. Look for terms like "pasteurized process cheese," "cheese food," or "cheese product" on labels, which indicate the absence of live cultures. For example, American singles or jarred cheese spreads are prime examples. If you’re aiming to incorporate live cultures into your diet, opt for raw or minimally processed cheeses like artisanal cheddar, Gouda, or blue cheese, which retain their microbial content. Pairing these with fermented foods like yogurt or sauerkraut can further amplify probiotic intake, particularly beneficial for adults over 50 whose gut health may naturally decline.

The absence of live cultures in processed cheeses isn’t inherently negative—it’s a matter of purpose. For individuals with weakened immune systems or those requiring sterile diets, processed cheeses offer a safe, predictable option. However, for health-conscious consumers, the lack of probiotics and potential presence of additives like sodium phosphate (used in doses up to 3% by weight) may outweigh the convenience. To strike a balance, consider using processed cheeses sparingly, such as in grilled cheese sandwiches, while reserving cultured cheeses for snacks or recipes where their microbial benefits can shine, like a probiotic-rich cheese board.

Ultimately, the choice between cultured and processed cheeses hinges on priorities. Processed varieties excel in versatility and shelf stability, making them ideal for busy households or specific dietary needs. Cultured cheeses, on the other hand, deliver a richer sensory experience and potential health perks. For instance, a study in the *Journal of Dairy Science* highlights that regular consumption of live-culture cheeses can enhance immune function in children aged 6–12. By understanding the differences, consumers can make informed decisions that align with their lifestyle, health goals, and culinary preferences.

Muenster Cheese Slice: Calorie Count and Nutritional Points Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, all cheese contains cultures, as bacteria or fungi cultures are essential for the fermentation and coagulation processes that transform milk into cheese.

Cheese cultures typically include lactic acid bacteria (e.g., Lactococcus, Lactobacillus) and sometimes molds (e.g., Penicillium) or yeast, depending on the cheese variety.

In aged or pasteurized cheeses, most cultures are no longer active, but in fresh or raw cheeses, some live cultures may still be present, contributing to flavor and potential probiotic benefits.