Cheese, a beloved dairy product enjoyed worldwide, is derived from cow's milk and inherently contains milk proteins, primarily casein and whey. Given its origins, it is natural to question whether cheese exerts similar effects as cow's milk protein, particularly in terms of nutrition, allergies, and health impacts. While both share common protein components, the fermentation and aging processes involved in cheese production alter its protein structure, potentially affecting digestibility and allergenicity. For instance, individuals with lactose intolerance may tolerate cheese better due to its lower lactose content, while those with milk protein allergies might still react to cheese depending on the specific proteins present. Understanding these differences is crucial for dietary considerations and managing health conditions related to cow's milk protein.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Protein Content | Cheese contains a significant amount of cow's milk protein, primarily casein and whey proteins, but in concentrated form due to the removal of water during production. |

| Lactose Content | Most cheeses have lower lactose levels compared to cow's milk, as lactose is largely removed during the cheesemaking process, making cheese more tolerable for lactose-intolerant individuals. |

| Allergenicity | Cheese retains the same milk proteins (e.g., casein, whey) that can trigger allergic reactions in individuals with cow's milk protein allergy (CMPA). |

| Digestibility | The fermentation process in cheesemaking can improve protein digestibility for some individuals, but it does not eliminate the allergenic properties of milk proteins. |

| Nutrient Profile | Cheese provides concentrated amounts of calcium, phosphorus, and vitamins (e.g., A, B12) found in cow's milk, but also higher fat and sodium content. |

| Immune Response | For those with CMPA, cheese can elicit the same immune response as cow's milk due to the presence of intact milk proteins. |

| Caloric Density | Cheese is more calorie-dense than cow's milk due to higher fat and protein concentration. |

| Fermented Properties | Some cheeses contain probiotics (e.g., in aged or fermented varieties), which are not present in cow's milk. |

| Shelf Life | Cheese generally has a longer shelf life than fresh cow's milk due to reduced moisture content and fermentation. |

| Culinary Use | Cheese is a versatile ingredient, unlike cow's milk, offering varied textures and flavors for cooking and consumption. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cheese vs. Milk Protein Content: Comparing protein levels in cheese and cow’s milk

- Allergenicity Differences: How cheese and milk proteins affect allergies differently

- Digestibility Factors: Cheese proteins are easier to digest than raw milk proteins

- Nutrient Retention: Cheese preserves or alters cow’s milk protein nutrients during processing

- Health Impact Variations: Cheese and milk proteins have distinct effects on human health

Cheese vs. Milk Protein Content: Comparing protein levels in cheese and cow’s milk

Cheese and cow’s milk are both dairy staples, but their protein content varies significantly due to the cheese-making process. A cup of whole cow’s milk contains approximately 8 grams of protein, while an equivalent weight of cheese can pack 20–30 grams, depending on the type. This disparity arises because cheese is essentially concentrated milk, with water and whey removed during production. For instance, hard cheeses like Parmesan or Cheddar have higher protein densities compared to softer varieties like mozzarella or Brie. Understanding this difference is crucial for anyone tracking protein intake, whether for fitness, dietary restrictions, or health goals.

Analyzing the protein quality in cheese versus milk reveals another layer of comparison. Both contain all nine essential amino acids, making them complete proteins. However, the protein in cheese is more bioavailable due to the breakdown of lactose and the presence of enzymes during fermentation. This means your body can absorb and utilize the protein in cheese more efficiently than that in milk, particularly for individuals with lactose intolerance. For example, a 30-gram serving of Cheddar cheese provides about 7 grams of protein, with a higher leucine content—an amino acid critical for muscle synthesis—compared to an equivalent calorie serving of milk.

For those aiming to increase protein intake, cheese offers a calorie-dense option, but portion control is key. A single ounce of cheese (about the size of your thumb) contains 6–8 grams of protein but also 90–120 calories, primarily from fat. In contrast, a cup of skim milk provides 8 grams of protein with only 80 calories. Athletes or individuals with higher protein needs might opt for cheese as a convenient snack, while those monitoring calorie intake may prefer milk. Pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like apples or whole-grain crackers can balance its fat content and stabilize blood sugar levels.

Practical tips for leveraging cheese and milk protein depend on your goals. If you’re a bodybuilder or active adult, incorporating 1–2 ounces of high-protein cheese (like Swiss or Gouda) post-workout can aid muscle recovery. For children or older adults, milk may be a better choice due to its calcium and vitamin D content, which support bone health. Pregnant women can benefit from both, but should prioritize pasteurized varieties to avoid foodborne illnesses. Always check labels for sodium content in cheese, as some types can exceed daily recommendations in small servings.

In conclusion, while cheese and cow’s milk share origins, their protein profiles cater to different needs. Cheese offers concentrated, highly absorbable protein but comes with higher calories and fat, making it ideal for specific dietary goals. Milk provides a lighter, more balanced option with added nutrients like calcium and vitamin B12. By understanding these differences, you can tailor your dairy choices to align with your health objectives, whether that’s muscle building, weight management, or overall nutrition.

Does Harry & David Cheese Require Refrigeration? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Allergenicity Differences: How cheese and milk proteins affect allergies differently

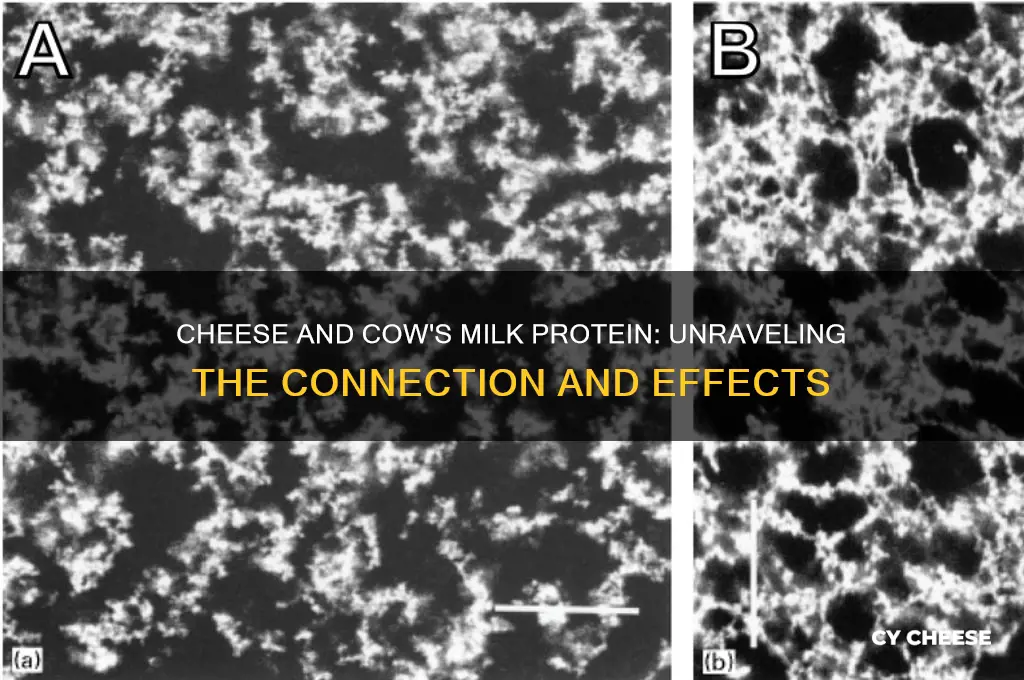

Cheese and milk, both derived from cow’s milk, contain the same primary proteins—casein and whey—yet their allergenicity differs significantly due to processing and composition changes. Milk allergies typically stem from these proteins, with whey (α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin) and casein triggering immune responses in sensitive individuals. However, during cheese production, whey is largely removed, leaving behind a higher proportion of casein. This alteration in protein distribution means that while milk allergies are often linked to both whey and casein, cheese allergies are predominantly associated with casein. For instance, individuals allergic to whey may tolerate cheese better than milk, as the whey content is significantly reduced during curdling and aging.

The fermentation and aging processes in cheese production further modify its protein structure, potentially reducing allergenicity. Enzymes like rennet break down milk proteins into smaller peptides, and bacterial cultures ferment lactose, altering the protein matrix. Studies suggest that these transformations can make cheese proteins less recognizable to the immune system, decreasing the likelihood of an allergic reaction. For example, hard cheeses like cheddar or Swiss undergo longer aging, which degrades proteins more extensively compared to soft cheeses like mozzarella. This explains why some milk-allergic individuals can consume aged cheeses without symptoms, while fresh cheeses may still provoke reactions.

Practical considerations for managing milk protein allergies highlight the importance of understanding these differences. For children under 5, who are most commonly affected by milk allergies, introducing cheese as a trial food can be a safer step than milk, given its lower whey content. However, this should only be done under medical supervision, as casein allergies still pose a risk. Adults with mild milk allergies may experiment with aged cheeses in small quantities (e.g., 10–15 grams) to assess tolerance, but soft or fresh cheeses should be avoided initially. Label reading is critical, as processed cheese products may contain added whey or milk proteins, increasing allergenic potential.

A comparative analysis reveals that while cheese and milk share origins, their allergenic profiles diverge due to processing. Milk’s liquid form retains all proteins in their native state, maximizing allergenicity, whereas cheese’s solidification and aging processes reduce whey and modify casein. This distinction is crucial for allergists and dietitians when advising patients. For instance, a milk-allergic individual might be prescribed a diet excluding milk but allowing aged cheeses, provided casein tolerance is confirmed. Such tailored approaches underscore the need to treat cheese and milk as distinct entities in allergy management.

In conclusion, the allergenicity of cheese and milk proteins is not interchangeable, despite their shared source. Cheese’s reduced whey content and altered protein structure offer a potential safe alternative for some milk-allergic individuals, particularly those sensitive to whey. However, casein remains a significant allergen in cheese, necessitating cautious introduction and professional guidance. Understanding these differences empowers both patients and healthcare providers to navigate dairy consumption more effectively, balancing nutritional needs with allergy management.

Chuck E. Cheese vs. Shane Dawson: The Lawsuit That Wasn't

You may want to see also

Digestibility Factors: Cheese proteins are easier to digest than raw milk proteins

Cheese, a beloved dairy product, undergoes a transformation during its production that significantly alters the digestibility of its proteins compared to raw cow's milk. This process, known as fermentation and curdling, breaks down complex milk proteins into simpler forms, making them gentler on the digestive system.

The Science Behind Easier Digestion:

During cheese making, milk is treated with bacteria and rennet, which cause it to curdle and separate into solids (curds) and liquid (whey). This process partially predigests the milk proteins, particularly casein, the primary protein in milk. The curds are then pressed and aged, further breaking down proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. These smaller molecules are more readily absorbed by the body, reducing the workload on the digestive enzymes.

As a result, individuals who struggle with digesting lactose or experience discomfort after consuming milk may find cheese to be a more tolerable option.

Practical Implications:

For those with mild lactose intolerance, opting for harder, aged cheeses like cheddar, Parmesan, or Swiss can be beneficial. These cheeses have lower lactose content due to the prolonged aging process, which allows bacteria to consume much of the lactose. Additionally, the reduced protein complexity in cheese can alleviate symptoms like bloating and gas associated with protein malabsorption.

However, it's crucial to note that individuals with severe lactose intolerance or milk protein allergies may still experience reactions to cheese, as some lactose and milk proteins remain.

Beyond Digestibility:

While cheese offers improved digestibility compared to raw milk, it's important to consider its overall nutritional profile. Cheese is generally higher in fat and sodium than milk, so moderation is key. Opting for low-fat cheese varieties and being mindful of portion sizes can help balance the benefits of easier digestion with overall dietary considerations.

Ultimately, understanding the digestibility factors of cheese allows individuals to make informed choices about incorporating this dairy product into their diet, potentially enjoying its unique flavor and nutritional benefits without the discomfort often associated with raw milk consumption.

Understanding Cheese Slice Weight: Grams in a Typical Slice

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Nutrient Retention: Cheese preserves or alters cow’s milk protein nutrients during processing

Cheese, a beloved dairy product, undergoes a transformative journey from its liquid milk origins, and this process significantly impacts the retention and alteration of cow's milk protein nutrients. The art of cheesemaking involves coagulation, drainage, and aging, each step playing a crucial role in shaping the final product's nutritional profile.

The Science of Coagulation: When milk is transformed into cheese, the first step is coagulation, where milk proteins, primarily casein, form a gel-like structure. This process is initiated by adding rennet or acidic substances, causing the milk to curdle. Interestingly, the coagulation process itself does not destroy the proteins but rather reorganizes them. The curds formed during this stage retain a significant amount of the original milk proteins, ensuring that the cheese becomes a concentrated source of these essential nutrients.

Nutrient Concentration: As the cheese curds are separated from the whey, the protein content becomes more concentrated. This concentration effect is particularly notable for whey proteins, which are often considered a valuable byproduct of cheesemaking. Whey protein isolates, for instance, are derived from this process and are renowned for their high biological value, containing all the essential amino acids. A mere 30 grams of whey protein isolate can provide over 25 grams of protein, making it a popular supplement for athletes and fitness enthusiasts.

Aging and Protein Transformation: The aging or ripening process in cheesemaking is where the magic happens in terms of flavor development and further protein alterations. During aging, specific enzymes and bacteria break down the milk proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids, enhancing digestibility. For example, aged cheeses like Parmesan or Cheddar have a more complex flavor profile due to these protein transformations. This process also contributes to the unique texture and aroma of different cheese varieties.

Practical Considerations: From a nutritional standpoint, the protein content in cheese can vary widely depending on the type and production methods. Hard cheeses, such as Parmesan, tend to have a higher protein concentration, with approximately 35-40% protein content. In contrast, softer cheeses may have a lower protein percentage but offer other nutritional benefits. When incorporating cheese into a diet, especially for those monitoring protein intake, it's essential to consider portion sizes. A 30-gram serving of hard cheese can provide around 10-12 grams of protein, making it a convenient snack or ingredient to boost protein consumption.

In summary, the journey from milk to cheese is a fascinating process that preserves and transforms cow's milk protein nutrients. Cheesemaking techniques ensure that the final product retains a substantial amount of protein while also creating unique nutritional profiles through aging and processing. Understanding these transformations allows consumers to make informed choices, appreciating cheese not only for its taste but also for its nutritional value.

Should You Remove the Rind from Gruyere Cheese? A Guide

You may want to see also

Health Impact Variations: Cheese and milk proteins have distinct effects on human health

Cheese and milk, both derived from cow’s milk, share a common protein source yet diverge significantly in their health impacts due to processing, composition, and bioavailability. Casein, the dominant protein in milk, is present in higher concentrations in cheese, often exceeding 25% of its total weight, compared to approximately 3-4% in whole milk. This concentration amplifies cheese’s potential effects on health, particularly in individuals with protein sensitivities or those monitoring dietary intake. For instance, a 30g serving of cheddar cheese provides about 7g of protein, equivalent to roughly 200ml of whole milk, but with added fat and sodium that further distinguish its metabolic effects.

Analyzing the digestive response reveals another layer of difference. Milk proteins are more rapidly absorbed due to their liquid form, making them a quick source of amino acids for muscle repair and energy. Cheese, however, undergoes fermentation and aging, which alters protein structure and slows digestion. This delayed absorption can lead to prolonged satiety, a benefit for weight management, but may also exacerbate discomfort in individuals with lactose intolerance or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Studies show that fermented dairy products like cheese reduce lactose content by up to 90%, yet the remaining lactose or other components like advanced glycation end products (AGEs) can still trigger symptoms in sensitive populations.

From a cardiovascular perspective, the fat content and type in cheese versus milk play a critical role. While whole milk contains saturated fats in a more diluted form, cheese’s higher fat density raises concerns about LDL cholesterol levels. However, research suggests that the calcium and protein in cheese may mitigate some of these effects by enhancing fat excretion. A 2019 study in *The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition* found that moderate cheese consumption (40g/day) did not significantly impact LDL levels in adults aged 40-65, unlike equivalent amounts of milk fat. This highlights the importance of portion control—limiting intake to one serving (30g) per day aligns with dietary guidelines to balance benefits and risks.

For bone health, both cheese and milk contribute calcium and phosphorus, but cheese’s higher sodium content can counteract these benefits by increasing calcium excretion. Adults over 50, particularly postmenopausal women, should monitor sodium intake while consuming cheese to avoid compromising bone density. Pairing cheese with potassium-rich foods like spinach or bananas can help neutralize sodium’s effects. Additionally, the vitamin K2 found in aged cheeses like Gouda or blue cheese supports calcium deposition in bones, offering a unique advantage over milk, which lacks this nutrient.

In practical terms, understanding these distinctions allows for tailored dietary choices. Athletes or those seeking rapid protein replenishment may opt for milk post-exercise, while individuals prioritizing sustained energy or lactose tolerance could favor cheese. Parents introducing dairy to children under 2 should prioritize milk for its balanced nutrient profile, reserving cheese for older toddlers in small portions to avoid excessive sodium intake. Ultimately, the key lies in recognizing that while cheese and milk share origins, their health impacts are shaped by processing, nutrient concentration, and individual physiological responses.

Does Laughing Cow Cheese Require Refrigeration? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, cheese is derived from cow's milk and contains the same proteins, primarily casein and whey, though in concentrated forms due to the cheese-making process.

It depends. Some individuals with a cow's milk protein allergy may react to cheese, as it still contains milk proteins. However, the aging process in certain cheeses can break down proteins, making them more tolerable for some.

No, cheese generally has lower lactose content than cow's milk because most lactose is removed during the cheese-making process. Hard cheeses typically have less lactose than soft cheeses.

Not always. Cheese is often easier to digest for lactose-intolerant individuals due to lower lactose levels. However, the concentrated protein content in cheese may cause different digestive responses compared to liquid milk.

Cheese is a good source of protein, but it also contains higher levels of fat and calories compared to cow's milk. The protein quality is similar, but the overall nutritional profile differs.