Cheese rind, the outer layer of many cheeses, often raises questions about its composition, particularly whether it contains wax. While some cheeses, like Gouda or Edam, are indeed coated with a thin layer of food-grade wax to preserve moisture and prevent spoilage, most cheese rinds are not made of wax. Instead, they are formed naturally during the aging process, consisting of molds, bacteria, or a mixture of curds and salt. Understanding the type of rind—whether it’s a hard, natural rind, a bloomy rind like that of Brie, or a waxed exterior—is essential for determining whether it’s edible or should be removed before consumption.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does Cheese Rind Have Wax? | Some cheese rinds have wax, but not all. Wax is primarily used as a protective coating on certain types of cheese, such as Cheddar, Gouda, and Edam, to prevent moisture loss and mold growth during aging. |

| Types of Cheese with Wax Rind | Cheddar, Gouda, Edam, Colby, and some artisanal cheeses. |

| Purpose of Wax on Cheese Rind | - Preserves moisture content - Prevents mold growth - Protects against contaminants - Extends shelf life |

| Is Wax Edible? | No, wax on cheese rinds is not edible and should be removed before consuming the cheese. |

| Alternatives to Wax | Natural rinds (e.g., mold-ripened cheeses like Brie), plastic coatings, or vacuum-sealed packaging. |

| How to Remove Wax | Peel or cut off the wax carefully before eating the cheese. |

| Environmental Impact | Wax coatings are generally considered more eco-friendly than plastic, as they are often derived from natural sources like beeswax or plant-based waxes. |

| Common Misconceptions | Not all hard cheeses have wax rinds; some have natural rinds or no rind at all. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Cheese Rinds: Natural, waxed, cloth-bound, and brined rinds explained

- Wax Purpose: Protects cheese from mold, moisture loss, and contamination

- Edible or Not: Most wax rinds are inedible; always check before consuming

- Removing Wax: How to safely peel or cut off wax before eating

- Alternatives to Wax: Paraffin, plastic, or natural coatings used in cheese-making

Types of Cheese Rinds: Natural, waxed, cloth-bound, and brined rinds explained

Cheese rinds are as diverse as the cheeses they protect, each type serving a unique purpose in flavor development, texture, and preservation. Among the most common are natural, waxed, cloth-bound, and brined rinds, each with distinct characteristics that influence the cheese’s final profile. Understanding these differences not only enhances appreciation but also guides proper handling and consumption.

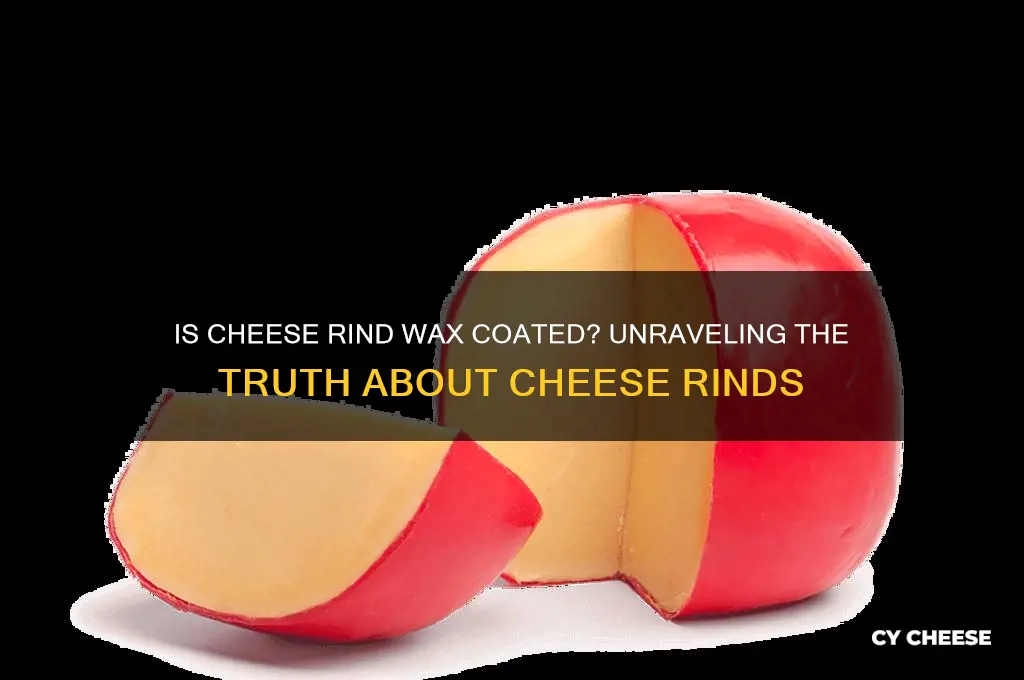

Natural rinds form organically during the aging process, often through exposure to air, bacteria, or molds. Examples include Brie and Camembert, where a velvety, edible white rind develops, contributing earthy, mushroom-like flavors. These rinds are typically thin and soft, making them safe to eat. Harder cheeses like aged Gouda may also develop natural rinds, though these are usually thicker and less palatable. To maximize flavor, pair natural-rind cheeses with wines or fruits that complement their earthy or nutty notes.

Waxed rinds serve a purely protective function, sealing the cheese to prevent moisture loss and external contamination. Commonly found on cheeses like Cheddar or Edam, the wax itself is flavorless and inedible. When using waxed cheeses, remove the wax carefully with a knife, ensuring no fragments remain. While waxed cheeses are often aged longer, their rinds do not contribute to flavor, making them ideal for those who prefer a pure, unadulterated cheese experience.

Cloth-bound rinds are traditional, particularly in British cheeses like Cheddar or Cheshire. The cloth absorbs moisture and allows controlled mold growth, imparting complex, savory flavors. These rinds are typically inedible but can be trimmed before serving. When storing cloth-bound cheeses, keep the cloth intact to maintain the aging process. For optimal flavor, allow the cheese to breathe at room temperature for 30–60 minutes before serving.

Brined rinds develop through immersion in a saltwater solution, as seen in Feta or Halloumi. This process creates a firm, edible rind that enhances the cheese’s tanginess and preserves freshness. Brined cheeses are versatile, suitable for grilling or crumbling into salads. To maintain their texture, store them in their original brine or a mixture of water and salt. When cooking, pat the cheese dry to achieve a golden crust without excessive oiliness.

Each rind type offers a unique sensory experience, from the creamy mouthfeel of natural rinds to the salty snap of brined varieties. By understanding their roles, cheese enthusiasts can better select, store, and savor these artisanal creations. Whether eaten or removed, the rind is never just a wrapper—it’s a storyteller, revealing the cheese’s journey from milk to masterpiece.

Cheese and Creatinine: Unraveling the Impact on Kidney Health

You may want to see also

Wax Purpose: Protects cheese from mold, moisture loss, and contamination

Cheese rinds often feature a waxy coating, but its purpose extends far beyond mere aesthetics. This protective layer serves as a barrier, shielding the cheese from external threats that could compromise its quality and safety. The primary function of wax on cheese rinds is threefold: preventing mold growth, minimizing moisture loss, and guarding against contamination. Each of these roles is critical in preserving the cheese’s texture, flavor, and shelf life, making wax an essential component in the art of cheesemaking.

Consider the process of applying wax to cheese. It’s not a random act but a precise technique. The wax is typically melted and brushed or poured onto the cheese in multiple thin layers, ensuring complete coverage. For optimal protection, food-grade paraffin or specialty cheese wax is used, as these materials are non-toxic and create a tight seal. The thickness of the wax layer matters too—too thin, and it may crack or fail to protect; too thick, and it can become cumbersome to remove. A general guideline is to apply 1-2 millimeters of wax, depending on the cheese’s size and intended aging period.

From a comparative standpoint, waxed cheeses often outlast their unwaxed counterparts. Take, for example, a wheel of Cheddar. Without wax, it would quickly dry out, develop mold, or absorb off-flavors from its environment. With wax, however, the same cheese can age gracefully, retaining its moisture and developing complex flavors over months or even years. This longevity is particularly valuable for hard and semi-hard cheeses, which benefit from extended aging. In contrast, soft cheeses like Brie or Camembert are rarely waxed, as their rinds are part of their character and flavor profile.

For home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, understanding the role of wax is key to successful cheese preservation. Start by ensuring the cheese is fully dried before waxing, as moisture trapped beneath the wax can lead to spoilage. Use a double-boiler method to melt the wax safely, avoiding direct heat that could cause it to burn or become too hot. Once applied, allow the wax to cool completely before handling the cheese. Store waxed cheeses in a cool, dry place, ideally at temperatures between 50°F and 55°F (10°C and 13°C), to maintain the wax’s integrity and the cheese’s quality.

In conclusion, the wax on cheese rinds is more than just a coating—it’s a functional shield that safeguards the cheese from mold, moisture loss, and contamination. By understanding its purpose and application, both professionals and hobbyists can ensure their cheeses age beautifully, delivering the intended flavors and textures. Whether you’re crafting cheese at home or selecting a wheel from the market, appreciating the role of wax enhances your cheesemaking and cheese-enjoying experience.

How Much Does a Bag of Shredded Cheese Cost?

You may want to see also

Edible or Not: Most wax rinds are inedible; always check before consuming

Cheese rinds often serve as protective barriers, but not all are created equal. While some natural rinds, like those on Brie or aged Gouda, are edible and enhance flavor, many cheeses are coated in wax for preservation. This wax is typically inedible, made from paraffin or petroleum-based materials, and should never be consumed. Before taking a bite, inspect the rind closely—if it appears smooth, uniform, and almost plastic-like, it’s likely wax and should be removed.

The confusion arises because waxed rinds resemble natural ones, especially on cheeses like Cheddar or Edam. To avoid accidental ingestion, check the packaging or consult a cheesemonger. Some artisanal cheeses use food-grade wax, which, while technically non-toxic, is still not meant for eating. As a rule of thumb, if the rind doesn’t look like it grew organically with the cheese, it’s probably wax. When in doubt, cut it off entirely.

Children and pets are particularly at risk, as they might mistake waxed cheese for a fully edible treat. Always supervise young ones during snack time and store waxed cheeses out of reach of curious pets. Ingesting wax can cause digestive discomfort, such as stomachaches or blockages, though it’s rarely severe. If accidental consumption occurs, monitor for symptoms and consult a healthcare provider if necessary.

For those who enjoy experimenting with cheese, here’s a practical tip: if you’re unsure whether a rind is wax or natural, perform a simple scratch test. Use a knife to gently scrape the surface—wax will flake off, while natural rinds will show texture or give way without peeling. Additionally, natural rinds often have irregularities, such as mold or color variations, whereas waxed rinds are consistently smooth. This quick check can save you from an unpleasant bite.

In conclusion, while cheese rinds can be a delightful part of the experience, waxed varieties are not meant to be eaten. Always verify the type of rind before consuming, especially with unfamiliar cheeses. By staying informed and cautious, you can safely enjoy your cheese without the risk of ingesting unwanted materials. Remember, when it comes to waxed rinds, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Cheese and Bacteria: Uncovering the Microbial Secrets in Every Bite

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.95

$14.95

Removing Wax: How to safely peel or cut off wax before eating

Cheese rinds can indeed be coated in wax, a protective layer that preserves freshness and prevents mold. While edible, this wax is not digestible and can detract from the cheese-eating experience. Removing it safely is straightforward but requires care to avoid contaminating the cheese.

Here’s how to do it effectively.

Steps for Removal: Begin by examining the wax for any seams or edges where it might lift easily. Use a clean, sharp knife to gently score along these lines, creating a starting point. For softer wax, a butter knife or the edge of a spoon can be sufficient. Peel back the wax slowly, working in small sections to avoid tearing or leaving residue. If the wax is particularly stubborn, warm the knife slightly under hot water to ease the process. For harder wax coatings, consider cutting it away in thin layers rather than attempting to peel it all at once.

Cautions: Avoid using excessive heat, as it can melt the wax onto the cheese surface. Never use a flame or direct heat source, as this risks damaging the cheese or creating a fire hazard. Be mindful of pressure—applying too much force can push wax fragments into the cheese. Always ensure your tools are clean to prevent introducing bacteria or contaminants.

Practical Tips: For cheeses with thin wax coatings, a vegetable peeler can be a useful tool, allowing for precise removal. If small wax pieces remain, use a damp cloth to wipe them away gently. Store the cheese in fresh wax paper or cheese wrap after removal to maintain its quality. For aged cheeses, consider leaving a thin layer of natural rind beneath the wax to preserve flavor and texture.

Perfect Pairings: Cheeses That Elevate Your Homemade Macaroni and Cheese

You may want to see also

Alternatives to Wax: Paraffin, plastic, or natural coatings used in cheese-making

Cheese rinds often serve as protective barriers, but not all are made of wax. While traditional wax coatings remain popular, modern cheesemakers explore alternatives like paraffin, plastic, and natural coatings to enhance preservation, texture, and sustainability. Each option carries distinct advantages and trade-offs, making the choice dependent on the cheese type, production scale, and environmental considerations.

Paraffin, a petroleum-based wax, is a common alternative due to its affordability and ease of application. It creates a moisture-resistant seal, ideal for semi-hard cheeses like Cheddar or Gouda. However, paraffin is non-biodegradable and can leave an oily residue, detracting from the cheese’s presentation. For small-scale producers, melting paraffin at 140–150°F (60–65°C) and brushing it onto the cheese in thin, even layers ensures a smooth finish. Caution: Avoid overheating, as paraffin can ignite above 392°F (200°C).

Plastic coatings, such as PVC or polyethylene, offer durability and consistency but raise environmental concerns. These coatings are often used in mass-produced cheeses for their ability to withstand transport and extend shelf life. However, plastic is not breathable, potentially trapping moisture and affecting flavor development. For artisanal cheesemakers, biodegradable plastic alternatives like polylactic acid (PLA) provide a middle ground, though they remain costlier. Application involves heat-shrinking the plastic around the cheese, requiring specialized equipment.

Natural coatings, such as plant-based waxes (soy or palm) or edible films (from milk proteins or algae), are gaining traction for their eco-friendliness. For instance, carnauba wax, derived from palm leaves, provides a glossy, breathable coating suitable for soft cheeses like Brie. Edible films, made by spraying a solution of casein or chitosan, offer a zero-waste option but require precise application techniques. These methods align with consumer demand for sustainability but may increase production costs.

When choosing an alternative, consider the cheese’s moisture content, aging time, and target market. Paraffin suits high-volume production, plastic excels in logistics, and natural coatings appeal to eco-conscious consumers. Experimentation is key—test small batches to evaluate texture, flavor, and appearance before scaling up. Ultimately, the right coating balances preservation, practicality, and principles, ensuring the cheese reaches its full potential.

Factors Influencing Milk Curdling in Cheese Making: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Some cheese rinds are coated with wax to preserve freshness and protect the cheese during aging, but not all cheese rinds have wax.

No, cheese wax is not edible and should be removed before consuming the cheese.

Cheese wax is typically smooth, shiny, and often colored (red, yellow, or black). It feels hard and non-porous, unlike natural rinds.

Yes, cheese wax can be cleaned, melted, and reused for coating homemade cheeses or other preservation purposes.