Blue cheese is unique for many reasons, but most significantly, it stands out from other cheeses because of the way it ripens. While most other cheeses are bacteria-ripened, blue cheeses ripen from mould activity. This mould is added to the milk during the cheesemaking process and remains dormant until the cheese is pierced, exposing it to oxygen and activating it. Blue mould can also occur accidentally in non-blue cheeses, like cheddar, when air inadvertently reaches the interior of the cheese and comes into contact with mould spores naturally present there.

Characteristics of Blue Cheese

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Main Structure | Aggregation of casein |

| Flavor | Spicy, savory, punchy, piquant, peppery, or slightly soapy |

| Formation | Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is sprinkled on top of the curds |

| Texture | Open |

| Whey Drainage | 10-48 hours |

| Salt | Acts as a preservative |

| Ripening Temperature | 8-10 degrees Celsius |

| Relative Humidity | 85-95% |

| Moisture Content | 46-47% |

| Milk Fat Content | 27-50% |

| Mold | Blue or green |

| Type of Cheese | Hard or soft |

| Preservation | Tupperware containers, parchment, plastic bags |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Blue mould spores are introduced into milk at the beginning of the cheesemaking process

Blue cheese is made from cow, goat, sheep, or even buffalo milk, which may be raw or pasteurized. The first step in making blue cheese is to mix raw milk with sterile salt to create a fermentation medium. A spore-rich Penicillium roqueforti culture is then added to the milk. This culture is what gives blue cheese its distinctive colour and flavour. The milk is then heated and pasteurized, and a starter culture is added to change the lactose to lactic acid, turning the milk from liquid to solid. This forms the curds, which are then ladled into containers to be drained and formed into a wheel of cheese.

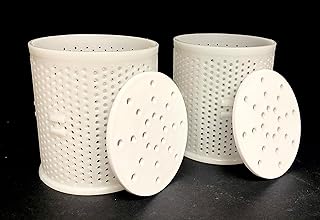

The blue mould spores are introduced at this stage, when the Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is sprinkled on top of the curds. The curds are then knit in moulds to form cheese loaves with a relatively open texture. Whey drainage continues for 10-48 hours, with the moulds inverted frequently to promote this process. Salt is then added to provide flavour and act as a preservative, and the cheese is salted for 24-48 hours.

The final step in the process is ripening the cheese by ageing it. The temperature and humidity in the room are carefully monitored to ensure the cheese does not spoil and maintains its optimal flavour and texture. The ripening temperature is usually around 8-10 degrees Celsius, with a relative humidity of 85-95%. The cheese loaves are also punctured to create small openings to allow air to penetrate and support the growth of the Penicillium roqueforti cultures, thus encouraging the formation of blue veins. The total ketone content is constantly monitored during this process, as the distinctive flavour and aroma of blue cheese come from methyl ketones, which are a metabolic product of the Penicillium roqueforti.

The piercing method is an important part of blue cheese production, as it allows oxygen to interact with the cultures in the cheese and promotes the growth of the blue mould from within. This method also allows cheesemakers to control the outcome of the blue cheese in terms of the amount of piercing, the ripening process, and the length of time the cheese is ripened.

Blue Cheese-Stuffed Olives: Are They Always Gluten-Free?

You may want to see also

Blue mould activates when exposed to oxygen

Blue mould, or Penicillium Roqueforti, is a type of fungus that is responsible for the distinctive blue veins and strong flavour of blue-veined cheeses. When exposed to oxygen, the mould activates and begins to grow, changing the texture and flavour of the cheese and turning it blue.

The process of making blue cheese involves adding the Penicillium Roqueforti culture to milk and allowing it to form curds. These curds are then drained and formed into cheese loaves, which are punctured to create small openings for air to penetrate and activate the mould. The temperature and humidity are carefully controlled during the ripening process to ensure the cheese develops the desired flavour and texture.

Not all blue cheese is created equal, however. Some varieties, like Gorgonzola, are made from sheep's milk and have a whiter colour and stronger flavour than those made from cow's milk. The specific characteristics of each type of blue cheese are influenced by the unique conditions and processes used during production.

It's worth noting that blue mould is not always intentionally added to cheese. In some cases, accidental bluing can occur in non-blue cheeses like cheddar or Cheshire. This happens when air reaches the interior of the cheese and comes into contact with mould spores naturally present in the environment. While this may be undesirable for some, others seek out these rare, accidentally blue cheeses for their unique flavour and texture.

In conclusion, the activation of blue mould when exposed to oxygen is a crucial step in the production of blue-veined cheese. This process contributes to the distinct flavour, texture, and appearance that is sought after by cheese enthusiasts worldwide.

Figs and Blue Cheese: A Perfect Pairing Appetizer

You may want to see also

Blue cheese ripens from the inside out

Blue cheese is made by adding cultures of edible moulds, which create blue-green spots or veins throughout the cheese. The mould used is called Penicillium, which is responsible for the distinct taste, smell, and appearance of blue cheese. During the cheesemaking process, Penicillium is added after the curds have been drained and formed into wheels. The cheese is then left to age for 2-3 months before it is ready to be consumed.

To make blue cheese, raw milk (from cattle, goats, or sheep) is mixed and pasteurized at 72 °C (162 °F) for 15 seconds. Then, a starter culture, such as Streptococcus lactis, is added to acidify the mixture, turning it from liquid to solid. After the curds have been formed, they are ladled into containers to be drained and formed into a full wheel of cheese. The Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is then sprinkled on top of the curds, along with Brevibacterium linens. The curds are then moulded into cheese loaves with a relatively open texture.

During the ripening process, the temperature and humidity in the room are carefully monitored to ensure the cheese does not spoil and maintains its optimal flavour and texture. The ripening temperature is generally kept between eight to ten degrees Celsius, with a relative humidity of 85-95%. At the beginning of this process, the cheese loaves are punctured to create small openings for air to penetrate, promoting the growth of the Penicillium roqueforti cultures and the formation of blue veins. The total ketone content is constantly monitored during ripening, as the distinctive flavour and aroma of blue cheese are a result of methyl ketones, which are metabolic products of Penicillium roqueforti.

Blue cheese can be stored in the refrigerator, where it will last for about 3-4 weeks if properly wrapped. It can also be frozen to extend its shelf life, although freezing may alter its texture and appearance. To prevent spoilage and ensure food safety, it is important to practice proper storage methods and regularly check for any changes in the appearance or smell of the cheese.

Blue Cheese and Candida: Is There a Connection?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Blue cheese is the only cheese that ripens from mould activity

Blue cheese is distinct from other cheeses in that it is the only type of cheese that ripens from mould activity. The mould in question is called Penicillium roqueforti, a fungus that plays a critical role in the production of interior mould-ripened cheeses. The fungus is added to the cheese milk as a spore-rich culture, and it is this that gives blue cheese its distinctive blue veins.

The process of making blue cheese starts with raw milk, which can come from cattle, goats, or sheep. This milk is then mixed and pasteurized at 72 °C (162 °F) for 15 seconds. Acidification occurs when a starter culture is added to the milk, turning lactose into lactic acid, and changing the milk's acidity, turning it from liquid to solid. Curds form due to the function of the enzyme rennet, which removes the hairy layer of casein micelles, allowing them to aggregate and form curds.

Once the curds have been formed, they are ladled into containers to be drained and formed into a full wheel of cheese. The Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is then sprinkled on top of the curds, along with Brevibacterium linens. The curds are then knit into moulds to form cheese loaves with an open texture. Whey drainage continues for 10-48 hours, with the moulds being inverted frequently to promote this process. Salt is then added to the cheese to provide flavour and act as a preservative.

The final step in the process is ripening the cheese by ageing it. During this time, the temperature and humidity of the room are monitored to ensure the cheese does not spoil and maintains its optimal flavour and texture. The ripening temperature is usually around 8-10°C with a relative humidity of 85-95%. At the beginning of the ripening process, the cheese loaves are punctured to create small openings to allow air to penetrate and support the growth of the Penicillium roqueforti cultures, thus encouraging the formation of blue veins. It is during this ripening process that the distinctive flavour and aroma of blue cheese arise from methyl ketones, which are a metabolic product of the Penicillium roqueforti.

Char Hut's Blue Cheese Burger: A Tasty Treat?

You may want to see also

Blue cheese gets its distinctive flavour from the mould

Blue cheese is unique for many reasons, but it stands out from other cheeses because of the way it ripens. While most cheeses are bacteria-ripened, blue cheeses ripen from mould activity. This mould, whose spores are introduced into milk at the beginning of the cheesemaking process, is blue. However, it won't grow unless oxygen is introduced.

Once oxygen is introduced, the mould activates, changing the texture, adding flavour, and turning the cheese blue. This process is often initiated by piercing the cheese with long, thin metal needles, which introduce oxygen to the inside of the cheese. Without the oxygen, blue mould can't grow. The more a cheese is pierced, the more its taste and appearance will be altered. When a Stilton cheese is pierced, for example, the blue flavour will be dominant.

Blue mould spores are added to the milk during the cheesemaking process, but they remain dormant until the cheese is pierced. When the piercing occurs, the mould inside the cheese becomes active, creating blue streaks that mature the cheese from the inside out. This turns a young, acidic, dry cheese into a softer, mellow, more broken-down cheese as it ages.

Blue Cheese Dressing: Gluten-Free or Not?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Blue cheese gets its colour from the mould that grows inside it. When the mould is exposed to oxygen, it activates, changing the texture, adding flavour, and turning the cheese blue.

Blue mould spores are introduced into milk at the beginning of the cheesemaking process. However, the mould remains dormant until the cheese is pierced, exposing it to oxygen and activating the mould.

The mould used to make blue cheese is called Penicillium roqueforti.

Yes, non-blue cheeses like Cheddar, Cheshire, Lancashire, and Wensleydale can turn blue during the maturation process. This usually happens when air inadvertently reaches the interior of the cheese and comes into contact with mould spores naturally present there.

In general, natural mould on cheese is not harmful to eat. Hard cheeses can be trimmed of mould and refrigerated, but soft cheeses should be discarded. However, if the cheese has developed black, grey, or red mould, it should be thrown away.