Cultured cheese often sparks curiosity about its production process, particularly whether it is pasteurized. Cultured cheese refers to cheese made using bacterial cultures to ferment milk, a process that not only develops flavor but also helps preserve the cheese. However, the term cultured does not inherently indicate whether the milk used was pasteurized or raw. Pasteurization is a separate step that involves heating milk to eliminate harmful bacteria, and it can be applied to milk before or after culturing. Therefore, cultured cheese can be made from either pasteurized or raw milk, depending on the producer’s methods and regional regulations. Understanding this distinction is crucial for consumers, especially those with concerns about food safety or preferences for raw milk products.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition of Cultured Cheese | Cheese made using bacterial cultures to ferment milk, creating lactic acid and curds. |

| Pasteurization Requirement | Not inherently pasteurized; depends on the milk used (pasteurized or raw). |

| Common Practice | Many cultured cheeses use pasteurized milk for safety and consistency. |

| Examples of Cultured Cheeses | Cheddar, Gouda, Mozzarella, Blue Cheese, Feta, Cream Cheese. |

| Raw Milk Cultured Cheese | Exists but less common due to regulatory restrictions in many regions. |

| Health Considerations | Pasteurized cultured cheese reduces risk of foodborne illnesses; raw milk versions may pose higher risks. |

| Flavor Differences | Raw milk cultured cheese often has more complex flavors due to natural bacteria. |

| Regulatory Standards | Varies by country; some mandate pasteurization for safety. |

| Labeling | Check labels for "pasteurized" or "raw milk" to confirm. |

| Shelf Life | Pasteurized versions generally have longer shelf life. |

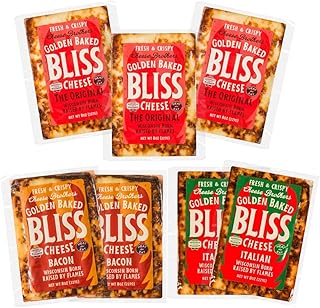

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Cultured Cheese: Cultured cheese is made with bacteria, not necessarily pasteurized

- Pasteurization Process: Pasteurization heats milk to kill bacteria, separate from culturing

- Cultured vs. Pasteurized: Culturing adds bacteria; pasteurization removes them, distinct processes

- Raw Milk Cultured Cheese: Cultured cheese can be made from raw, unpasteurized milk

- Safety Considerations: Pasteurized cultured cheese reduces pathogens; raw cultured cheese carries risks

Definition of Cultured Cheese: Cultured cheese is made with bacteria, not necessarily pasteurized

Cultured cheese is a product of bacterial fermentation, a process that transforms milk into a solid, flavorful food. Unlike common assumptions, the term "cultured" does not inherently imply pasteurization. Instead, it refers to the deliberate introduction of specific bacteria, such as *Lactococcus lactis* or *Streptococcus thermophilus*, to coagulate milk and develop flavor. These bacteria convert lactose into lactic acid, lowering the pH and causing milk proteins to curdle. Pasteurization, which involves heating milk to destroy pathogens, is a separate step that may or may not precede culturing, depending on the cheese-making process.

To clarify, cultured cheese can be made from either raw or pasteurized milk. Raw milk cheeses, like traditional French Camembert or Swiss Gruyère, rely on naturally occurring bacteria and are cultured without pasteurization. In contrast, cheeses made from pasteurized milk, such as American cheddar or mozzarella, are inoculated with specific bacterial cultures after the milk has been heated. The choice between raw and pasteurized milk impacts texture, flavor, and safety, with raw milk cheeses often boasting more complex flavors but carrying a higher risk of foodborne illness.

For home cheese makers, understanding this distinction is crucial. If using raw milk, ensure it is sourced from a reputable supplier with rigorous testing for pathogens. When culturing pasteurized milk, select high-quality bacterial cultures tailored to the desired cheese type. For example, mesophilic cultures are ideal for soft cheeses like Brie, while thermophilic cultures suit hard cheeses like Parmesan. Always follow precise temperature and time guidelines, as deviations can disrupt bacterial activity and compromise the final product.

From a health perspective, cultured cheese offers probiotic benefits, particularly when made with live, active cultures. These beneficial bacteria can support gut health, though pasteurized cheeses may lose some probiotic properties due to heat treatment. For those with lactose intolerance, cultured cheeses are often easier to digest, as bacterial fermentation breaks down lactose. However, individuals with weakened immune systems should exercise caution with raw milk cheeses, opting for pasteurized varieties to minimize risk.

In summary, cultured cheese is defined by its bacterial fermentation, not pasteurization. Whether made from raw or pasteurized milk, the culturing process is central to its creation. By understanding this distinction, consumers and cheese makers alike can make informed choices, balancing flavor, safety, and health benefits. Cultured cheese remains a versatile and nutritious food, its character shaped by the interplay of bacteria, milk, and technique.

Perfect Cracker Pairings for Cheese and Caramel Dip: A Tasty Guide

You may want to see also

Pasteurization Process: Pasteurization heats milk to kill bacteria, separate from culturing

Cultured cheese and pasteurized cheese are often conflated, but the pasteurization process is distinct from culturing. Pasteurization involves heating milk to a specific temperature—typically 161°F (72°C) for 15 seconds in high-temperature, short-time (HTST) pasteurization—to eliminate harmful bacteria like *Salmonella* and *E. coli*. This step is crucial for safety, particularly in large-scale production, as it reduces the risk of foodborne illnesses. Culturing, on the other hand, introduces beneficial bacteria (e.g., *Lactobacillus* or *Streptococcus*) to ferment milk sugars into lactic acid, which coagulates the milk and develops flavor. While pasteurization targets pathogens, culturing is about transformation, not sterilization.

The separation of these processes is intentional. Pasteurizing milk before culturing ensures a clean slate, removing competitors to the desired starter cultures. However, some artisanal cheesemakers use raw (unpasteurized) milk, relying on the culturing process itself to outcompete harmful bacteria. This approach is riskier but can yield complex flavors due to the diverse microbial environment. For home cheesemakers, pasteurizing milk at 145°F (63°C) for 30 minutes is a safer alternative to HTST, though it requires careful temperature monitoring to avoid scorching.

A key takeaway is that pasteurization and culturing serve different purposes. Pasteurization is a safety measure, while culturing is a flavor and texture developer. For example, pasteurized milk can still be cultured to make cheeses like cheddar or mozzarella, but the starting microbial profile differs from raw milk. Understanding this distinction helps consumers and producers make informed choices, balancing safety with sensory experience.

Practical tips for those working with pasteurized milk include selecting high-quality starter cultures to compensate for the lack of native bacteria. Additionally, avoid overheating during pasteurization, as it can denature proteins and affect curd formation. For raw milk enthusiasts, sourcing from reputable farms with rigorous testing protocols minimizes risks. Ultimately, whether pasteurized or raw, the culturing process remains the heart of cheese making, turning milk into a diverse array of flavors and textures.

Understanding the White Skin on Brie Cheese: A Tasty Mystery Explained

You may want to see also

Cultured vs. Pasteurized: Culturing adds bacteria; pasteurization removes them, distinct processes

Cultured cheese and pasteurized cheese are often confused, but their processes are fundamentally opposite. Culturing involves introducing specific bacteria to milk, which ferment lactose into lactic acid, thickening the milk and creating flavor. This step is essential for cheeses like cheddar, gouda, and brie, where bacterial activity drives texture and taste. Pasteurization, on the other hand, heats milk to 161°F (72°C) for at least 15 seconds, killing harmful pathogens and most bacteria. While pasteurization ensures safety, it eliminates the live cultures needed for culturing, making the two processes mutually exclusive in their core functions.

Consider the practical implications for cheese production. Cultured cheeses rely on live bacteria to develop their characteristic profiles, often requiring aging to deepen flavors. For example, blue cheese depends on *Penicillium* molds introduced during culturing. Pasteurized cheeses, however, start with milk stripped of bacteria, limiting their ability to develop complex flavors without additional steps. This distinction is why raw milk cheeses (unpasteurized and cultured) are prized for their depth, while pasteurized cheeses often require added cultures or flavorings to compensate.

From a health perspective, the choice between cultured and pasteurized cheese matters. Cultured cheeses, especially those made with live cultures, can support gut health by introducing beneficial bacteria. For instance, aged cheeses like Swiss or cheddar retain probiotic strains like *Lactobacillus*. Pasteurized cheeses, while safer for immunocompromised individuals or pregnant women, lack these live cultures. However, pasteurization’s heat treatment ensures the absence of pathogens like *Listeria* or *Salmonella*, making it a critical step for mass-produced cheeses.

For home cheesemakers, understanding these processes is key. Culturing requires precise temperature control (typically 85–100°F or 29–38°C) and specific bacterial cultures, such as mesophilic or thermophilic strains. Pasteurization, while simpler in theory, demands accurate temperature monitoring to avoid scorching the milk. Combining both processes—pasteurizing milk before adding cultures—is common in artisanal cheesemaking, balancing safety with flavor development. Always use a reliable thermometer and follow recipes closely to ensure success.

In summary, culturing and pasteurization serve distinct roles in cheesemaking. Culturing builds flavor and texture through bacterial activity, while pasteurization prioritizes safety by eliminating pathogens. Neither process implies the other; a cheese can be cultured but unpasteurized (raw milk), pasteurized but uncultured (processed cheese), or both pasteurized and cultured (many artisanal varieties). Understanding this difference empowers consumers and makers alike to choose or craft cheeses that align with their priorities, whether flavor, safety, or both.

Do All Dogs Love Cheese? Uncovering the Canine-Cheese Connection

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Raw Milk Cultured Cheese: Cultured cheese can be made from raw, unpasteurized milk

Cultured cheese made from raw, unpasteurized milk is a tradition that predates modern pasteurization by centuries. This process relies on naturally occurring bacteria and enzymes in the milk to ferment and coagulate it, creating complex flavors and textures that pasteurized milk often struggles to replicate. Artisanal cheesemakers prize raw milk for its inherent microbial diversity, which contributes to the unique terroir of their cheeses. However, this method requires meticulous hygiene and handling to minimize the risk of harmful pathogens, making it a labor-intensive but rewarding craft.

For those interested in crafting raw milk cultured cheese at home, the process begins with sourcing high-quality, fresh raw milk from a trusted dairy. Start by warming the milk to around 86°F (30°C) and adding a mesophilic starter culture, which introduces beneficial bacteria to initiate fermentation. After 45 minutes to an hour, add rennet to coagulate the milk. Once the curd sets, cut it into small pieces, stir gently, and allow it to release whey. The curds are then drained, salted, and pressed into molds. Aging times vary by cheese type—soft cheeses like Camembert may age for 2–4 weeks, while harder cheeses like Gruyère can take 6 months or more.

The debate over raw milk cultured cheese often centers on safety versus flavor. Pasteurization destroys pathogens but also neutralizes many of the enzymes and bacteria that contribute to a cheese’s character. Raw milk cheeses, when properly handled, retain these elements, resulting in richer, more nuanced profiles. However, they carry a higher risk of contamination, particularly for vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, young children, and immunocompromised individuals. Regulatory standards for raw milk cheeses are stringent in many countries, requiring extended aging times (e.g., 60 days in the U.S.) to reduce pathogen risks.

Comparatively, pasteurized milk cultured cheeses are more forgiving for beginners and offer a safer option for widespread consumption. Yet, raw milk enthusiasts argue that the trade-off in flavor and nutritional integrity is significant. Raw milk cheeses contain higher levels of beneficial bacteria, vitamins, and enzymes, which some claim aid digestion and enhance health. For those willing to navigate the challenges, raw milk cultured cheese represents a bridge between ancient traditions and modern culinary artistry, offering a taste of history in every bite.

Optimal Harvest Time for Outdoor-Grown Exodus Cheese: A Guide

You may want to see also

Safety Considerations: Pasteurized cultured cheese reduces pathogens; raw cultured cheese carries risks

Cultured cheese, whether pasteurized or raw, undergoes a fermentation process that introduces beneficial bacteria, but the safety profiles of the two differ significantly. Pasteurization, a heat treatment process, effectively eliminates harmful pathogens such as *Listeria*, *Salmonella*, and *E. coli*, which can cause severe foodborne illnesses. For instance, pregnant women are often advised to avoid raw cultured cheeses like unpasteurized Camembert or Brie due to the risk of *Listeria* infection, which can lead to miscarriage or severe neonatal complications. In contrast, pasteurized versions of these cheeses retain their flavor profiles while offering a safer alternative for vulnerable populations.

The fermentation process in cultured cheese does reduce pathogen levels naturally, but it does not guarantee complete elimination. Beneficial bacteria like *Lactobacillus* and *Streptococcus* compete with harmful microbes, lowering pH levels and creating an inhospitable environment for pathogens. However, this natural defense is not foolproof, especially in raw cheese. For example, a study published in the *Journal of Food Protection* found that while fermentation reduced *Salmonella* counts in raw milk cheeses, detectable levels remained in some samples. Pasteurization, on the other hand, consistently reduces pathogen levels to below detectable limits, providing a critical safety net.

When choosing between pasteurized and raw cultured cheese, consider the trade-offs between risk and reward. Raw cultured cheese enthusiasts argue that it offers superior flavor complexity and a richer microbial profile, which may contribute to gut health. However, this comes with a higher risk of contamination, particularly for immunocompromised individuals, young children, and the elderly. Pasteurized cultured cheese, while slightly milder in flavor, is a safer option for everyday consumption. For example, pasteurized cheddar or Gouda can be used in dishes like grilled cheese sandwiches or cheese boards without the worry of pathogen exposure.

Practical tips can help mitigate risks when consuming raw cultured cheese. Always check labels for pasteurization status, and store raw cheese at or below 40°F (4°C) to slow bacterial growth. Avoid raw cultured cheese if you fall into a high-risk category, and opt for pasteurized alternatives instead. For those who enjoy raw cheese occasionally, pair it with foods high in antimicrobial properties, such as garlic or honey, to further reduce risk. Ultimately, understanding the safety considerations allows consumers to make informed choices that balance flavor preferences with health priorities.

Are Cheeseburgers Halal? Exploring Ingredients and Religious Dietary Laws

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Not necessarily. Cultured cheese refers to cheese made using bacterial cultures, but it does not automatically mean the milk used was pasteurized. Some cultured cheeses are made with raw milk.

No, cultured cheese is not always pasteurized. Pasteurization is a separate process from culturing, and some artisanal or traditional cheeses use raw milk even when bacterial cultures are added.

Yes, cultured cheese can be made with unpasteurized (raw) milk. The term "cultured" only indicates the use of bacterial cultures, not the milk's pasteurization status.

No, the term "cultured" does not imply pasteurization. It simply means the cheese was made using bacterial cultures. To know if the cheese is pasteurized, check the label for terms like "pasteurized milk" or "made with pasteurized milk."