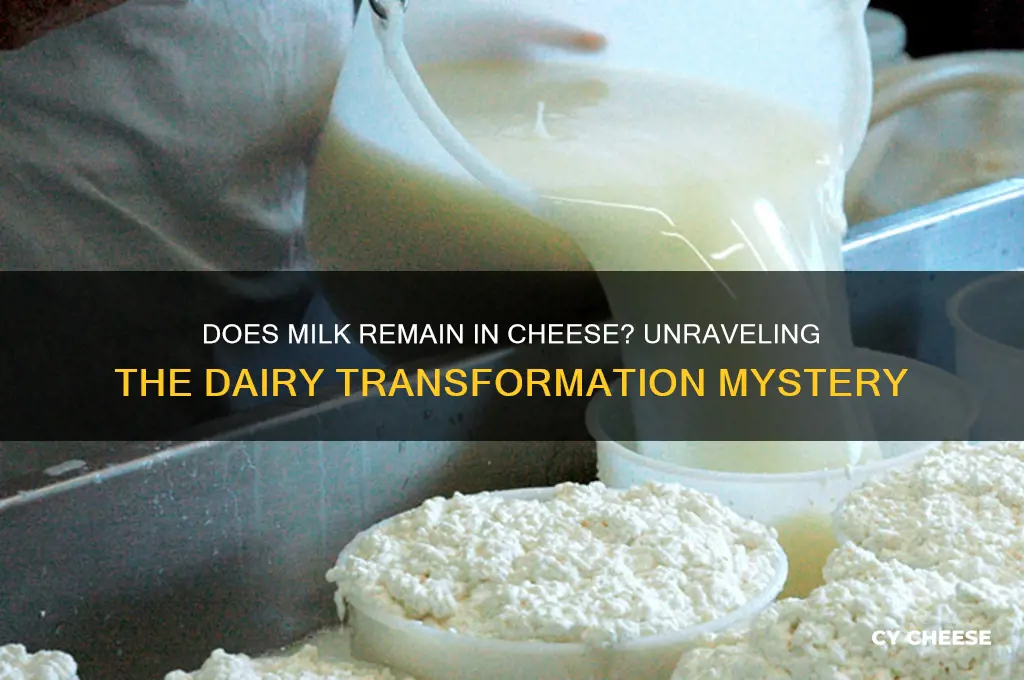

The question of whether milk remains in cheese is a common curiosity among both food enthusiasts and those with dietary restrictions. Cheese is a dairy product made by curdling milk, typically from cows, goats, or sheep, and then separating the solid curds from the liquid whey. During this process, much of the milk’s liquid components are removed, but the curds retain proteins, fats, and some lactose. While the final product is significantly transformed from its original state, trace amounts of milk components, such as casein proteins and residual lactose, may still be present in cheese. However, the extent to which milk remains depends on the type of cheese and its production method, making it a nuanced topic for those with lactose intolerance or milk allergies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Milk Presence | Trace amounts of milk proteins (e.g., casein, whey) remain in cheese, but lactose is significantly reduced or absent in most aged cheeses. |

| Lactose Content | Hard and aged cheeses (e.g., cheddar, parmesan) contain <0.1 g lactose per 100 g, while softer cheeses (e.g., mozzarella, brie) may retain slightly more. |

| Protein Content | Cheese retains milk proteins, with ~20-30 g protein per 100 g, depending on the type. |

| Fat Content | Cheese contains milk fats, ranging from 20-35% depending on the variety (e.g., whole milk vs. low-fat cheese). |

| Allergenicity | Milk allergens (e.g., casein, whey) remain in cheese, making it unsuitable for those with milk allergies. |

| Lactose Intolerance | Most aged cheeses are tolerated by lactose-intolerant individuals due to minimal lactose content. |

| Processing | Cheese-making processes (curdling, pressing, aging) remove most lactose and whey, leaving behind solids (curds). |

| Nutritional Value | Cheese retains calcium, phosphorus, and vitamins (e.g., A, B12) from milk, but in concentrated forms. |

| Fermentation | Fermentation by bacteria and molds during aging breaks down lactose and alters milk components, creating unique flavors and textures. |

| Shelf Life | Cheese has a longer shelf life than milk due to reduced moisture content and preservation techniques (e.g., aging, salting). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Milk Solids in Cheese: Understanding how much milk protein and fat remain during cheese production

- Whey Separation Process: How whey is removed, leaving milk solids to form cheese

- Cheese Moisture Content: Role of remaining milk moisture in cheese texture and shelf life

- Milk Allergens in Cheese: Presence of milk proteins like casein and lactose in cheese

- Fermentation Impact: How bacteria and enzymes transform milk into cheese, retaining key components

Milk Solids in Cheese: Understanding how much milk protein and fat remain during cheese production

Cheese is essentially concentrated milk, but the transformation process significantly alters the composition of milk solids. During cheesemaking, milk is curdled, and the liquid whey is drained off, leaving behind a solid mass rich in proteins and fats. However, not all milk components remain in equal proportions. For instance, while most of the milk protein (casein) is retained, a portion of the lactose and minerals is lost in the whey. Understanding this transformation is crucial for anyone interested in the nutritional content or dietary implications of cheese.

Consider the starting point: a liter of whole cow’s milk typically contains around 3.5–5% fat, 3.5% protein, and 4.5% lactose. When this milk is converted into cheese, the concentration of milk solids increases dramatically. For example, a 30-gram serving of cheddar cheese requires approximately 250–300 grams of milk, depending on the variety. This means that while the fat and protein content per gram of cheese is higher, the overall lactose content is significantly reduced, making cheese a more tolerable option for those with lactose intolerance. However, the exact retention of milk solids varies based on cheese type, with fresh cheeses like mozzarella retaining more moisture and harder cheeses like Parmesan being more concentrated.

To illustrate, let’s compare two popular cheeses: mozzarella and Parmesan. Mozzarella, a fresh cheese, retains about 50% of the original milk’s moisture, resulting in a softer texture and lower concentration of milk solids. In contrast, Parmesan, a hard cheese, loses over 85% of its moisture during aging, leaving behind a product that is approximately 30% protein and 28% fat by weight. This concentration explains why Parmesan delivers a more intense flavor and higher calorie density per gram compared to mozzarella. Such differences highlight the importance of cheese type in determining milk solid retention.

For those monitoring dietary intake, understanding milk solids in cheese can be a practical tool. A 30-gram serving of cheddar, for example, provides about 7 grams of protein and 9 grams of fat, derived from the milk used in its production. This makes cheese a nutrient-dense food, particularly beneficial for meeting protein and calcium needs. However, it’s essential to account for sodium content, which can vary widely—Parmesan contains around 150 mg of sodium per 30-gram serving, while fresh cheeses like ricotta have significantly less. Pairing this knowledge with portion control allows for informed choices, especially for individuals with dietary restrictions or health goals.

Finally, the retention of milk solids in cheese has implications beyond nutrition. For instance, the high protein and fat content contributes to cheese’s satiety, making it a filling snack or ingredient. Additionally, the concentration of milk solids influences texture, meltability, and flavor profile, which are critical factors in culinary applications. Whether you’re selecting cheese for a charcuterie board or a grilled cheese sandwich, understanding how milk solids are preserved during production can enhance both the nutritional and sensory experience. This knowledge bridges the gap between science and kitchen, offering practical insights for cheese enthusiasts and health-conscious consumers alike.

Should You Keep Grated Cheese in the Fridge? Tips for Freshness

You may want to see also

Whey Separation Process: How whey is removed, leaving milk solids to form cheese

Milk, a complex mixture of proteins, fats, and lactose, undergoes a remarkable transformation during cheese-making. The whey separation process is the pivotal step where this liquid gold is divided into its solid and liquid components, setting the stage for cheese formation. This process begins with the addition of rennet or acid to milk, causing it to curdle. The curds, rich in casein proteins and fat, will become the foundation of cheese, while the whey, a greenish-yellow liquid, carries away the water-soluble components like lactose and whey proteins. Understanding this separation is key to appreciating how milk’s essence is concentrated into cheese.

The whey separation process is both an art and a science, requiring precision and timing. After coagulation, the curds are cut into smaller pieces to release more whey. This step, known as "scalding," is temperature-sensitive; for example, cheddar curds are heated to 39-42°C (102-108°F) to expel additional whey and create a firmer texture. The curds are then stirred and allowed to settle, a process called "syneresis," where whey continues to drain. In industrial settings, mechanical presses may be used to expedite this step, ensuring maximum whey removal. Proper whey separation is critical, as residual whey can affect the cheese’s moisture content, shelf life, and flavor profile.

From a practical standpoint, home cheesemakers can replicate this process with simple tools. Start by heating milk to the desired temperature (e.g., 30°C/86°F for soft cheeses) and adding a coagulant like diluted rennet (typically 1-2 drops per gallon of milk). After curdling, use a long knife to cut the curds into 1-inch cubes, stirring gently for 10-15 minutes to release whey. Line a mold with cheesecloth, transfer the curds, and allow the whey to drain for several hours or overnight. For harder cheeses, additional pressing may be required. Always sanitize equipment to prevent contamination, and monitor pH levels (aiming for 6.0-6.4) to ensure proper curd formation.

Comparatively, the whey separation process in artisanal and industrial cheese-making differs in scale but not principle. Artisanal methods often rely on time and gravity, emphasizing natural drainage and aging for flavor development. Industrial processes, however, prioritize efficiency, using centrifuges to separate whey rapidly and standardize production. Despite these differences, both approaches achieve the same goal: isolating milk solids to create cheese. The whey, once a byproduct, is now a valuable commodity, used in protein supplements, animal feed, and even skincare products, showcasing the sustainability of this ancient process.

In conclusion, the whey separation process is a testament to the ingenuity of cheese-making. By removing whey, milk’s solids are concentrated, preserving its nutritional value and transforming it into a diverse array of cheeses. Whether you’re a hobbyist or a professional, mastering this step ensures the creation of high-quality cheese. From the delicate curd handling to the precise temperature control, every detail matters in this alchemical process that turns liquid milk into a solid, savory delight.

Cheeseburger Secrets: Who Puts Cheese Inside the Burger in TN?

You may want to see also

Cheese Moisture Content: Role of remaining milk moisture in cheese texture and shelf life

Milk does remain in cheese, but not in its original form. During cheesemaking, moisture from milk is partially removed through processes like curdling, cutting, and pressing. The amount of moisture retained in the final cheese product, known as cheese moisture content, is a critical factor influencing texture and shelf life. This moisture, primarily whey trapped within the curd matrix, acts as a plasticizer, softening the cheese structure. Higher moisture content results in softer, more spreadable cheeses like mozzarella (50-60% moisture) or fresh cheeses like ricotta (55-70% moisture). Conversely, harder cheeses like Parmesan (30-35% moisture) or Cheddar (35-45% moisture) undergo longer aging and pressing to reduce moisture, creating a denser, more crumbly texture.

Understanding the role of remaining milk moisture allows cheesemakers to manipulate texture and shelf life. For instance, controlling pressing time and temperature during production directly impacts moisture retention. Additionally, aging conditions, such as humidity and temperature, further influence moisture loss over time, affecting both texture and the growth of desirable molds and bacteria that contribute to flavor development.

Consider the example of Brie, a soft cheese with a bloomy rind. Its high moisture content (around 50%) creates a creamy interior, but also requires careful handling and refrigeration to prevent spoilage. In contrast, aged Gouda, with its lower moisture content (35-40%), has a firmer texture and longer shelf life, making it suitable for room temperature storage and extended aging.

This highlights the delicate balance between moisture content, texture, and shelf life in cheese. While remaining milk moisture is essential for texture, excessive moisture can accelerate spoilage due to microbial growth. Cheesemakers employ various techniques, including salting, pH control, and specific aging conditions, to manage moisture levels and ensure both desirable texture and safe, extended shelf life.

For home cheesemakers, controlling moisture content is crucial for achieving desired results. Recipes often specify target moisture ranges for different cheese types. Monitoring curd moisture during pressing and adjusting aging conditions (humidity, temperature) are key steps. For softer cheeses, shorter pressing times and higher humidity during aging are recommended. Harder cheeses require longer pressing and drier aging conditions. Remember, even small variations in moisture content can significantly impact the final product, so careful attention to detail is essential for successful cheesemaking.

Grating Cheese: Chemical Change or Physical Transformation Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Milk Allergens in Cheese: Presence of milk proteins like casein and lactose in cheese

Cheese is a dairy product, and as such, it inherently contains milk proteins. For individuals with milk allergies, understanding the presence and persistence of these proteins in cheese is crucial. Milk proteins, primarily casein and whey, are not eliminated during the cheese-making process. In fact, casein constitutes about 80% of the proteins in cow’s milk and remains a dominant component in cheese. This means that even small amounts of cheese can trigger allergic reactions in sensitive individuals. For example, a single 30-gram serving of cheddar cheese contains approximately 7 grams of protein, the majority of which is casein. Parents and caregivers should be particularly cautious with young children, as milk allergies are most prevalent in infants and toddlers, affecting up to 2-3% of this age group.

Lactose, another milk component, is a sugar that often raises concerns for those with lactose intolerance. However, the lactose content in cheese is significantly reduced during production. Hard cheeses like Parmesan or Swiss contain less than 1 gram of lactose per serving, making them more tolerable for lactose-intolerant individuals. Yet, for those with a milk allergy, lactose is not the primary concern—milk proteins are. Soft cheeses, such as ricotta or cream cheese, retain slightly more lactose but still pose a greater risk due to their high protein content. It’s essential to read labels carefully, as some processed cheese products may contain added milk solids, increasing allergen exposure.

For individuals managing milk allergies, avoiding cheese entirely is often the safest option. However, this can be challenging, as cheese is a staple in many diets and cuisines. Cross-contamination is another risk, as shared equipment in food production facilities can introduce milk proteins into seemingly non-dairy products. For instance, a study found that 10% of dark chocolate bars tested positive for casein due to shared manufacturing lines. To mitigate risks, allergists recommend carrying an epinephrine auto-injector and educating oneself on hidden sources of milk proteins. Apps like Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE) can help identify safe products and dining options.

Comparatively, plant-based cheese alternatives have gained popularity as a milk-free option. These products are typically made from nuts, soy, or coconut and are free from casein and lactose. However, they may not replicate the texture or flavor of traditional cheese, and some individuals may have allergies to the alternative ingredients. For example, almond-based cheeses are unsuitable for those with nut allergies. When transitioning to plant-based options, it’s important to verify that the product is manufactured in a dairy-free facility to avoid cross-contamination.

In conclusion, milk proteins like casein remain present in cheese, posing a significant risk for those with milk allergies. While lactose content is minimal in most cheeses, it is the proteins that trigger allergic reactions. Practical steps include reading labels meticulously, avoiding cross-contamination, and exploring plant-based alternatives. For parents, caregivers, and individuals with allergies, staying informed and prepared is key to safely navigating dietary choices. Always consult a healthcare professional for personalized advice and management strategies.

Why the Quarter Pounder is Royale with Cheese in Europe

You may want to see also

Fermentation Impact: How bacteria and enzymes transform milk into cheese, retaining key components

Milk undergoes a profound transformation when it becomes cheese, yet its essence remains. At the heart of this metamorphosis are bacteria and enzymes, microscopic architects that dismantle and rebuild milk’s structure while preserving its nutritional core. Fermentation, the process driven by these agents, coagulates milk proteins, breaks down lactose, and concentrates fats, all while retaining key components like calcium, protein, and vitamins. This biological alchemy not only extends milk’s shelf life but also enhances its digestibility and flavor complexity.

Consider the role of *Lactococcus lactis*, a bacterium commonly used in cheese production. When introduced to milk, it consumes lactose and produces lactic acid, lowering the pH and causing casein proteins to curdle. This step is critical, as it separates milk into curds (solid) and whey (liquid), yet the curds still contain the milk’s original proteins, fats, and minerals. Enzymes like rennet further refine this process by cleaving specific protein bonds, ensuring a firmer texture without sacrificing nutritional integrity. The result? A product where milk’s fundamental elements persist, albeit in a transformed state.

Practical application of fermentation requires precision. For home cheesemakers, maintaining a temperature of 30°C (86°F) during fermentation is crucial for optimal bacterial activity. Adding 1/4 teaspoon of starter culture per gallon of milk ensures consistent results, while a 1:10,000 dilution of rennet in water (e.g., 0.1 mL rennet in 1 mL water) provides the right enzymatic dosage. Over-fermentation risks bitterness, while under-fermentation yields a crumbly texture, so timing—typically 12–24 hours—must be monitored. These steps illustrate how controlled fermentation retains milk’s essence while crafting cheese’s unique character.

Comparatively, unfermented dairy products like fresh mozzarella or paneer rely solely on acid or heat coagulation, often losing whey and its soluble nutrients. Cheese, however, harnesses fermentation to preserve and concentrate milk’s benefits. For instance, a 30g serving of cheddar retains 7g of protein and 200mg of calcium, comparable to an 8oz glass of milk. This efficiency makes cheese a nutrient-dense alternative, particularly for lactose-intolerant individuals, as fermentation reduces lactose by up to 99%. Thus, fermentation not only transforms milk but also optimizes its nutritional delivery.

In essence, fermentation is a delicate balance of science and art, where bacteria and enzymes act as both destroyers and creators. They dismantle milk’s original form while safeguarding its vital components, proving that milk does indeed remain in cheese—reimagined, intensified, and immortalized. For those exploring dairy’s potential, understanding this process unlocks a world where tradition and biology converge to create a food both ancient and ever-evolving.

Subway Chicken Bacon Ranch: Double Cheese or Single Layer?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, milk is the primary ingredient in cheese, and its components (such as proteins, fats, and lactose) are transformed during the cheesemaking process, but they still remain in the final product.

Most cheeses contain very little to no lactose because it is largely removed during the curdling and aging process, though soft, fresh cheeses may retain small amounts.

Yes, milk proteins like casein and whey are the foundation of cheese and remain in the final product, though they are altered during coagulation and aging.

Cheese is more concentrated in nutrients like protein, fat, and calcium compared to milk because the cheesemaking process removes water and lactose while retaining these components.

It depends on the type of allergy. Those allergic to milk proteins (casein or whey) may still react to cheese, as these proteins remain in the product. However, some individuals with lactose intolerance may tolerate certain cheeses due to their low lactose content.