Moldy cheese can indeed emit a strong, unpleasant odor, often described as pungent or musty, which many people find off-putting. While some cheeses, like blue cheese, naturally contain mold as part of their flavor profile, the smell of mold on other types of cheese is typically a sign of spoilage. The stench arises from volatile organic compounds produced by the mold as it breaks down the cheese, signaling that the cheese may no longer be safe or palatable to consume. Understanding the difference between intentional mold in certain cheeses and harmful mold growth is crucial for both culinary enjoyment and food safety.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Odor | Moldy cheese can have a strong, pungent, or ammonia-like smell, depending on the type of mold and cheese. |

| Appearance | Visible mold growth, which can be white, green, blue, or black, often with a fuzzy or powdery texture. |

| Texture | The affected area may become soft, slimy, or discolored, while the rest of the cheese might remain firm. |

| Taste | If consumed, it can taste bitter, sour, or unpleasant, though some aged cheeses with specific molds are intentionally consumed. |

| Health Risks | Can cause allergic reactions, respiratory issues, or food poisoning if consumed, especially for individuals with weakened immune systems. |

| Safe Consumption | Hard cheeses (e.g., cheddar, Parmesan) can be salvaged by cutting off moldy parts with a 1-inch margin. Soft cheeses (e.g., Brie, cottage cheese) should be discarded entirely if moldy. |

| Prevention | Store cheese properly (refrigerated, wrapped in wax or parchment paper) and consume within recommended timeframes. |

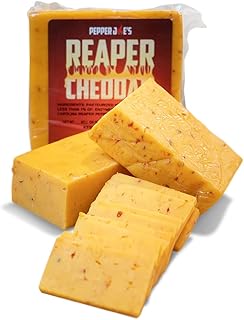

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Moldy Cheese: Brie, Camembert, Gorgonzola, Roquefort, Stilton, and other common moldy cheeses

- Odor Causes: Mold enzymes break down cheese proteins, releasing volatile compounds causing strong smells

- Safe vs. Unsafe: Some moldy cheeses are edible; others can produce harmful toxins if spoiled

- Aging Process: Controlled mold growth during aging contributes to unique flavors and aromas

- Storage Tips: Proper refrigeration and wrapping reduce mold growth and minimize odor

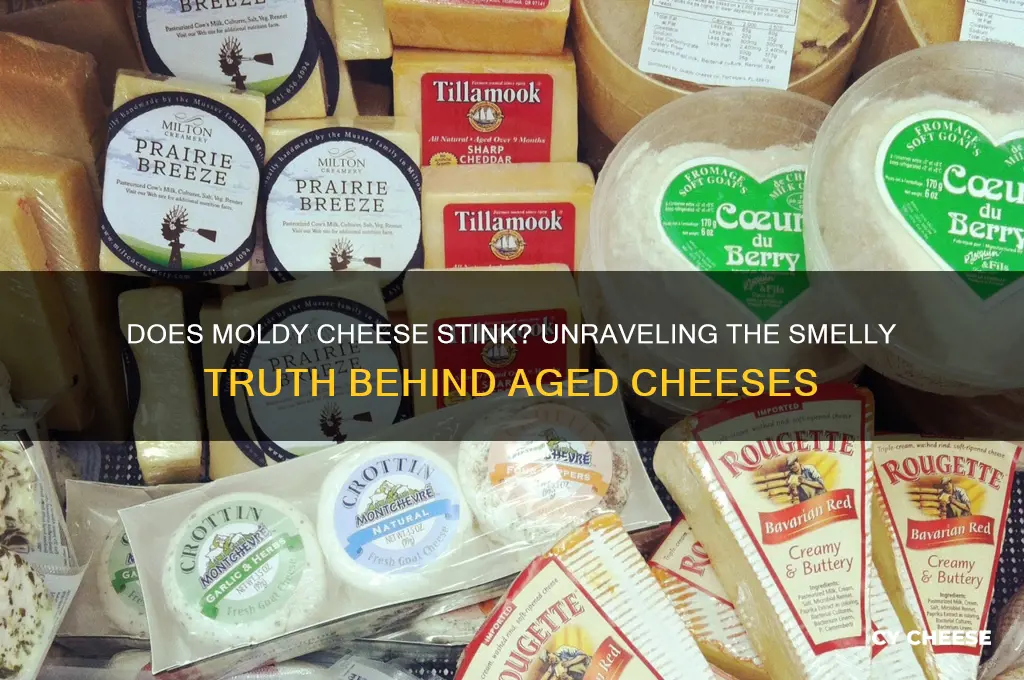

Types of Moldy Cheese: Brie, Camembert, Gorgonzola, Roquefort, Stilton, and other common moldy cheeses

Moldy cheese doesn’t always stink—in fact, the presence of mold in certain cheeses is a deliberate and celebrated part of their creation. Take Brie and Camembert, for instance. These soft-ripened cheeses develop a velvety white rind as Penicillium camemberti works its magic. The aroma here is earthy and mushroomy, far from offensive. It’s the mold’s job to break down the cheese’s interior, creating that signature creamy texture. If you detect an ammonia-like smell, however, it’s a sign the cheese has over-ripened and should be discarded.

Next, consider Gorgonzola, Roquefort, and Stilton—blue cheeses that owe their distinctive veining to Penicillium roqueforti. These cheeses carry a stronger, pungent aroma that some might initially mistake for stink. But it’s a complexity that pairs beautifully with sweet accompaniments like honey or fruit. The mold in these cheeses is not just for show; it contributes to their tangy, salty flavor profile. If the smell becomes sharp or acrid, though, it’s a red flag—the cheese has likely spoiled.

Not all moldy cheeses are created equal, and understanding their aging process is key. For example, Brie and Camembert are typically ready to eat after 4–6 weeks of aging, while Gorgonzola can take 2–3 months. Roquefort, aged in the cool, damp caves of southern France, matures for at least 3 months. The longer aging times of blue cheeses often result in stronger odors, but these are part of their charm, not a sign of spoilage.

If you’re unsure whether your moldy cheese has gone bad, trust your senses. Sight, smell, and touch are your best tools. Healthy mold should appear uniform in color and texture. If you spot black, pink, or orange mold, or if the cheese feels slimy, it’s time to toss it. For soft cheeses likeMoldy cheese doesn’t inherently stink—it’s the *type* of mold and its interaction with the cheese that determines the aroma. Brie and Camembert, for instance, are soft-ripened cheeses with white mold rinds (Penicillium camemberti). Their scent is earthy, mushroomy, and slightly ammoniated when perfectly ripe. If they’re overripe, however, they emit a sharp, ammonia-heavy odor that signals spoilage, not just maturity. The key? Trust your nose: a mild, savory aroma is good; a pungent, chemical smell is not.

Gorgonzola and Roquefort, both blue cheeses, introduce a different dynamic. Their veins of Penicillium roqueforti or glaucum produce a sharper, more assertive smell—think tangy, spicy, and slightly metallic. This is intentional and desirable, but there’s a fine line between complex and overpowering. If the cheese smells sour or like wet cardboard, it’s gone too far. Pro tip: store blue cheeses wrapped in wax paper, not plastic, to let them breathe without drying out.

Stilton, another blue cheese, shares similarities with Roquefort but carries a more robust, nutty aroma with a hint of sweetness. Its mold (Penicillium roqueforti) thrives in the damp, cool caves of Derbyshire, contributing to its distinct profile. When pairing, consider the cheese’s intensity: Stilton’s boldness pairs well with port, while milder Gorgonzola works with honey or pears. Always inspect the veins—if they’re slimy or discolored, discard it.

Other mold-ripened cheeses, like Humboldt Fog or Saint-Marcellin, showcase how mold type and aging affect aroma. Humboldt Fog’s thin layer of ash and mold creates a subtle, tangy scent, while Saint-Marcellin’s creamy interior develops a pungent, barnyard-like aroma as it ages. Rule of thumb: softer cheeses spoil faster and more noticeably. If the smell is off-putting or the texture is slimy (not just runny), it’s time to toss it.

Understanding these nuances transforms moldy cheese from a potential hazard to a culinary delight. Each variety has its own olfactory signature, and learning to distinguish between ripe and spoiled is essential. For example, a faint ammonia smell in Brie is normal, but a strong one isn’t. Similarly, blue cheeses should smell sharp but not sour. When in doubt, err on the side of caution—but don’t let fear keep you from enjoying the complex flavors these cheeses offer.

Overcooked Cheese: Texture, Flavor, and Salvaging Tips Explained

You may want to see also

Odor Causes: Mold enzymes break down cheese proteins, releasing volatile compounds causing strong smells

Moldy cheese doesn’t just look unappetizing—it often smells overpowering. This pungent odor isn’t random; it’s the result of a precise biological process. When mold colonizes cheese, its enzymes begin breaking down complex proteins into simpler compounds, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs). These VOCs are lightweight molecules that evaporate easily, carrying the distinctive "stink" into the air. Think of it as the mold’s metabolic byproduct, a chemical signature of its activity. This process is why even a small patch of mold can produce a smell that fills a room.

To understand the intensity, consider the types of VOCs released. Mold enzymes, such as proteases, target cheese proteins like casein, cleaving them into amino acids and peptides. Certain amino acids, like methionine, degrade further into sulfur-containing compounds like methanethiol, which has a putrid, cabbage-like odor. Even trace amounts of these compounds—as little as 1 part per billion—can be detected by the human nose. This explains why moldy cheese often smells "rotten" or "acrid," depending on the mold species and cheese type. For instance, *Penicillium* molds on blue cheese produce milder, earthy VOCs, while *Mucor* or *Rhizopus* on aged cheddar release sharper, more offensive ones.

If you’re assessing whether to salvage moldy cheese, the odor is a critical indicator. Hard cheeses like Parmesan or Cheddar can sometimes be saved by cutting away the moldy part plus an inch of surrounding cheese, but only if the smell is faint. Strong, penetrating odors suggest the VOCs have spread beyond the visible mold, making the entire piece unsafe. Soft cheeses, however, are a lost cause once mold appears—their porous structure allows VOCs and toxins to permeate quickly. Always err on the side of caution: if it stinks, toss it.

Practical tip: Store cheese properly to slow mold growth and VOC production. Wrap it in wax or parchment paper (not plastic, which traps moisture) and keep it in the coldest part of the fridge, ideally below 40°F (4°C). For longer storage, freeze hard cheeses in portions, as freezing halts enzymatic activity. If mold does appear, dispose of the cheese in a sealed bag to prevent the VOCs from contaminating other foods. Understanding the science behind the stink not only helps you manage cheese waste but also ensures you avoid accidental foodborne illness.

Grapes on Cheese Boards: A Perfect Pairing Explained

You may want to see also

Safe vs. Unsafe: Some moldy cheeses are edible; others can produce harmful toxins if spoiled

Moldy cheese doesn’t always signal danger, but it demands scrutiny. Certain cheeses, like Brie or Camembert, develop edible molds as part of their aging process, contributing to their distinctive flavors and textures. These molds are intentionally introduced and carefully controlled, making them safe to consume. However, not all molds are benign. Unwanted molds on cheeses like Cheddar or Swiss can produce harmful mycotoxins, invisible compounds that pose serious health risks even in small amounts. The key lies in identifying whether the mold is part of the cheese’s design or an uninvited intruder.

To distinguish safe from unsafe mold, consider the cheese’s type and appearance. Soft cheeses with mold as part of their character, such as Gorgonzola or Roquefort, are generally safe to eat, though any surface mold should be trimmed off before consumption. Hard cheeses, on the other hand, are more susceptible to harmful molds. If you spot mold on a hard cheese, discard at least one inch around the affected area, as mycotoxins can penetrate deeper than visible mold. Never consume moldy cheese if you’re pregnant, immunocompromised, or have allergies, as the risks are amplified for these groups.

The sensory test—does it stink?—can offer clues but isn’t definitive. Edible molds often have earthy, nutty, or tangy aromas, while harmful molds may produce musty, sour, or ammonia-like smells. However, relying solely on smell is risky, as mycotoxins are odorless. Instead, prioritize visual inspection and knowledge of the cheese’s intended mold characteristics. When in doubt, err on the side of caution and discard the cheese, as the potential health risks far outweigh the cost of replacement.

Practical tips can help minimize mold growth and ensure safety. Store cheese properly—wrap hard cheeses in wax or parchment paper and keep them in the coldest part of the refrigerator. Soft cheeses should be stored in their original packaging or wrapped loosely to allow breathing. Regularly inspect cheese for mold, especially if it’s past its prime. For those who frequently deal with leftover cheese, consider freezing hard varieties, as freezing halts mold growth. By combining knowledge, vigilance, and proper storage, you can safely enjoy moldy cheeses meant to be savored while avoiding those that pose hidden dangers.

Can Cheese Alter Stomach pH? Unraveling the Digestive Impact of Dairy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Aging Process: Controlled mold growth during aging contributes to unique flavors and aromas

Mold, when left unchecked, can indeed produce unpleasant odors, but in the world of cheese, it's a different story. The aging process of cheese involves a delicate dance with mold, where controlled growth transforms potential stench into a symphony of flavors and aromas. This is not a mere coincidence but a result of meticulous craftsmanship and scientific precision.

Consider the iconic blue cheeses, such as Roquefort or Stilton. These varieties rely on the introduction of specific mold cultures, like Penicillium roqueforti, during the aging process. The mold grows within the cheese, creating veins of blue or green that contribute to its distinctive taste and smell. Contrary to what one might expect, the mold's presence doesn't lead to a putrid odor. Instead, it produces a complex bouquet of aromas, ranging from earthy and nutty to sweet and spicy. This is achieved through careful monitoring of temperature, humidity, and aging time, ensuring the mold's growth remains within desirable parameters.

The key to this process lies in understanding the role of mold in breaking down the cheese's proteins and fats. As the mold grows, it releases enzymes that degrade these components, resulting in the formation of various flavor compounds. For instance, the breakdown of proteins can lead to the creation of amino acids and peptides, some of which have distinct tastes and smells. The type and amount of mold, as well as the aging conditions, dictate the specific flavors produced. In the case of blue cheeses, the mold's activity can generate methyl ketones, responsible for their characteristic pungency, and isovaleric acid, contributing to a sweaty, cheesy aroma.

To achieve the desired flavor profile, cheesemakers follow precise protocols. For blue cheeses, the process often involves piercing the cheese with needles to allow oxygen penetration, encouraging mold growth. The cheese is then aged in controlled environments, with temperatures typically ranging from 7-13°C (45-55°F) and high humidity levels. The aging period can vary from a few weeks to several months, depending on the desired intensity of flavor. For example, a young Roquefort might age for 2-3 months, while an older, more robust version could mature for up to 6 months.

In contrast to the controlled mold growth in cheese aging, uncontrolled mold in food is a different matter. When mold grows unchecked, it can produce mycotoxins, which are harmful substances that can cause food to stink and become unsafe for consumption. This is why the art of cheese aging is a delicate balance, requiring expertise and precision. Cheesemakers must ensure that the mold cultures used are safe and that the aging conditions prevent the growth of undesirable molds. This involves regular monitoring, adjusting environmental factors, and sometimes even hand-turning the cheeses to ensure even mold distribution.

The beauty of this process is that it showcases how a potentially undesirable element, mold, can be harnessed to create something extraordinary. Through the aging process, cheese transforms from a simple dairy product into a complex, flavorful experience. It's a testament to the power of controlled fermentation and the skill of artisans who understand the science behind it. So, the next time you savor a piece of mold-ripened cheese, remember that its unique aroma and taste are the result of a carefully orchestrated aging process, where mold is not something to be avoided but embraced as a key ingredient in the cheese's character.

Unlocking Cheese Escape: Decoding the Four-Digit Mystery

You may want to see also

Storage Tips: Proper refrigeration and wrapping reduce mold growth and minimize odor

Mold growth on cheese is a common issue, but its accompanying odor can be a more pressing concern. The smell of moldy cheese ranges from mildly unpleasant to overwhelmingly pungent, depending on the type of mold and the cheese’s age. Proper storage is key to mitigating both mold development and the resulting stench. Refrigeration at the right temperature—ideally between 35°F and 38°F (2°C and 3°C)—slows microbial activity, while wrapping cheese in materials like wax or parchment paper, rather than plastic, allows it to breathe without drying out. These simple steps can significantly extend a cheese’s freshness and reduce the likelihood of encountering that unmistakable, off-putting aroma.

Consider the mechanics of mold and odor production. Mold spores thrive in damp, warm environments, breaking down cheese proteins and releasing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) responsible for the stink. By controlling humidity and temperature through proper refrigeration, you disrupt this process. For instance, hard cheeses like cheddar should be stored in the lower, colder part of the fridge, while softer varieties like Brie benefit from slightly warmer conditions. Wrapping cheese in specialized cheese paper or beeswax wraps further regulates moisture, preventing the condensation that mold craves. These methods not only preserve texture and flavor but also minimize the odor that often signals spoilage.

A comparative look at storage methods reveals the pitfalls of common mistakes. Plastic wrap, though convenient, traps moisture against the cheese’s surface, creating an ideal breeding ground for mold. Conversely, leaving cheese unwrapped exposes it to air, causing it to dry out and lose flavor. The middle ground lies in breathable materials like parchment paper or reusable silicone wraps, which balance moisture retention and airflow. For example, wrapping semi-soft cheeses like Gouda in cheese paper and storing them in the crisper drawer can extend their life by up to two weeks. Such practices not only reduce mold but also ensure the cheese remains palatable without emitting a foul odor.

Persuasive arguments for proper storage extend beyond odor control. Moldy cheese, while sometimes safe to consume after removing the affected area, can still harbor toxins that permeate the entire piece. By minimizing mold growth through correct refrigeration and wrapping, you reduce health risks associated with mycotoxins. Additionally, the financial benefit of preserving expensive artisanal cheeses cannot be overstated. Investing in a dedicated cheese storage container or simply using the right wrapping materials pays dividends in both taste and longevity. The takeaway is clear: a little effort in storage goes a long way in avoiding the stench and waste of spoiled cheese.

Chick-fil-A Mac and Cheese: A Creamy, Cheesy Delight Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Not always. Some moldy cheeses, like blue cheese, have a strong but intentional aroma, while others may develop an unpleasant odor if spoiled.

Yes, a foul or ammonia-like smell is a clear sign the cheese has gone bad, whereas a mild, earthy scent may indicate it’s still safe in some cases.

It depends on the type of cheese and mold. Soft cheeses tend to stink more when moldy compared to harder cheeses or other foods due to their higher moisture content.