The age-old question of whether old cheese tastes better is a subject of much debate among cheese enthusiasts and culinary experts alike. As cheese ages, its flavor profile evolves, often becoming more complex, intense, and nuanced due to the breakdown of proteins and fats, as well as the development of beneficial bacteria and molds. Harder cheeses like Parmesan or aged Gouda can develop deep, nutty, and caramelized notes, while softer cheeses like Brie may exhibit richer, earthy, and tangy characteristics. However, the preference for aged cheese ultimately depends on individual taste, as some may find the stronger flavors overpowering or the texture too crumbly or dry. Thus, while aging can enhance the taste of cheese for many, it’s not a universal rule, and the better flavor is often a matter of personal preference and the specific type of cheese in question.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Flavor Intensity | Older cheeses generally have more complex and intense flavors due to prolonged aging, which allows for the development of deeper, nuttier, and sometimes sharper or tangy notes. |

| Texture | Aged cheeses tend to be firmer, drier, and sometimes crumbly, compared to younger cheeses, which are often softer and creamier. |

| Aroma | Older cheeses typically have stronger, more pronounced aromas, often described as earthy, fruity, or even pungent. |

| Umami Quality | Aging increases the umami (savory) flavor in cheese, making it more satisfying and rich in taste. |

| Complexity | The flavor profile of aged cheese is more layered, with nuances that can include caramel, butterscotch, or even hints of brothy or meaty flavors. |

| Saltiness | Older cheeses may perceive as saltier due to moisture loss during aging, concentrating the salt content. |

| Pairing Potential | Aged cheeses often pair better with bold wines, nuts, fruits, and charcuterie due to their robust flavors. |

| Shelf Life | Longer aging usually results in a longer shelf life, as the cheese becomes less hospitable to bacteria due to reduced moisture. |

| Cost | Older cheeses are typically more expensive due to the extended aging process and higher labor and storage costs. |

| Preference | Taste is subjective; some prefer the mildness of young cheese, while others enjoy the boldness of aged varieties. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Aging Process Enhances Flavor

The transformation of cheese over time is a delicate dance of microbiology and chemistry, where each passing day brings a new layer of complexity to its flavor profile. As cheese ages, its moisture content decreases, concentrating the proteins and fats that give it structure and taste. This natural dehydration process is not merely a preservation technique but a catalyst for flavor development. For instance, a young cheddar might offer a mild, creamy experience, but as it matures over 12 to 24 months, it develops sharp, tangy notes with a crumbly texture that many aficionados find irresistible.

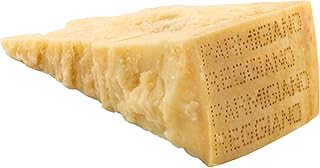

Consider the role of enzymes and bacteria in this aging process. These microscopic workers break down complex compounds into simpler, more flavorful molecules. In blue cheeses like Roquefort or Gorgonzola, the introduction of Penicillium mold creates veins of pungent, earthy flavors that intensify with age. Similarly, hard cheeses such as Parmigiano-Reggiano rely on long aging periods—up to 36 months—to develop their signature nutty, umami-rich profiles. The longer the cheese ages, the more pronounced these flavors become, often accompanied by a crystalline texture that adds a satisfying crunch.

For those looking to experiment with aged cheeses, understanding the optimal aging conditions is key. Temperature and humidity play critical roles; most cheeses thrive in cool (around 50°F or 10°C) and humid (80-85%) environments. Home enthusiasts can replicate this by storing cheese in a dedicated refrigerator drawer with a humidity-controlled container. Regularly flipping the cheese and monitoring its progress ensures even aging and prevents mold overgrowth. For example, a semi-hard cheese like Gruyère can be aged at home for 6 to 12 months, gradually revealing its complex, slightly sweet, and caramelized flavors.

However, aging cheese is not without its challenges. Over-aging can lead to an unpleasantly bitter taste or an overly hard texture, rendering the cheese difficult to enjoy. It’s essential to taste the cheese periodically and assess its development. If you’re aging multiple varieties, keep detailed notes on each cheese’s starting point, aging conditions, and flavor evolution. This practice not only helps refine your technique but also deepens your appreciation for the art of cheesemaking.

In conclusion, the aging process is a transformative journey that elevates cheese from a simple dairy product to a culinary masterpiece. By understanding the science behind aging, controlling environmental factors, and practicing patience, anyone can unlock the full potential of cheese’s flavor. Whether you’re a casual enthusiast or a dedicated connoisseur, the rewards of aging cheese are well worth the effort, offering a sensory experience that only time can perfect.

Cheese String Sugar Content: Unveiling the Grams in Your Snack

You may want to see also

Texture Changes Over Time

As cheese ages, its texture undergoes a metamorphosis, transforming from supple to rigid, crumbly to crystalline. This evolution is a testament to the intricate interplay between moisture loss, fat crystallization, and protein breakdown. Hard cheeses like Parmigiano- Reggiano, for instance, develop a granular texture as tyrosine crystals form within their matrix, creating a satisfying crunch that contrasts with their initial smooth, pliable state.

Consider the aging process as a delicate dance, where time and environment dictate the texture's trajectory. A 6-month aged Gouda will retain a semi-soft, supple texture, ideal for slicing and melting. In contrast, a 24-month aged Gouda will become firm, flaky, and slightly granular, better suited for grating or savoring in small, flavorful shards. To appreciate these changes, conduct a sensory experiment: compare a young and old version of the same cheese, noting the differences in mouthfeel, density, and structural integrity.

The science behind texture changes is rooted in moisture migration and fat redistribution. As cheese ages, moisture evaporates, concentrating flavors and causing proteins to tighten. Simultaneously, fat molecules rearrange, forming larger crystals that contribute to a drier, more brittle texture. For example, a 12-month aged Cheddar will exhibit a smoother, more fudgy texture compared to a 36-month aged Cheddar, which will be drier, more crumbly, and punctuated with crunchy tyrosine crystals.

To optimize texture development, control aging conditions meticulously. Maintain a consistent temperature (ideally between 50-55°F) and humidity (around 85-90%) to encourage gradual moisture loss without case hardening. Regularly flip and brush the cheese to prevent mold growth and ensure even drying. For home aging, invest in a small aging fridge or create a makeshift environment using a cooler, hygrometer, and humidity-regulating materials like damp cloth or brine-soaked sponges.

Ultimately, the texture of aged cheese is a sensory experience that rewards patience and attention to detail. By understanding the mechanisms driving texture changes, you can anticipate and appreciate the unique characteristics of each aging stage. Whether you prefer the creamy decadence of a young Brie or the crystalline crunch of an aged Alpine cheese, recognizing the role of time and technique in texture development will deepen your enjoyment of this ancient, ever-evolving food.

Red Velvet Cupcake Wine and Cheese Pairing: A Perfect Match?

You may want to see also

Mold Development Impact

Mold development is a double-edged sword in the world of aged cheese, capable of elevating flavor or ruining it entirely. The key lies in understanding which molds are desirable and how to control their growth. Beneficial molds, such as *Penicillium camemberti* in Camembert or *Penicillium roqueforti* in blue cheese, break down proteins and fats, releasing complex compounds that contribute to depth and richness. However, unwanted molds like *Aspergillus* or *Mucor* can introduce off-flavors or even toxins, rendering the cheese unsafe. Monitoring humidity, temperature, and airflow during aging is critical to fostering the right mold colonies while suppressing harmful ones.

To harness mold’s potential, consider the aging environment. Ideal conditions for most aged cheeses include a temperature range of 50–55°F (10–13°C) and relative humidity of 85–95%. For blue cheeses, introducing mold spores via inoculation ensures consistent development. Home cheesemakers should use food-grade molds and avoid cross-contamination by sanitizing tools and surfaces. Regularly inspect the cheese for discoloration or unusual odors, as these may indicate unwanted mold growth. If caught early, trimming affected areas can salvage the cheese, but discard it if the mold appears fuzzy, green, or black, as these are signs of spoilage.

The impact of mold on flavor is both scientific and artistic. As molds metabolize, they produce enzymes that hydrolyze proteins into amino acids and fats into fatty acids, creating savory, nutty, or earthy notes. For instance, the white rind of Brie owes its creamy texture and mushroom-like flavor to *Penicillium camemberti*. In contrast, overgrowth can lead to bitterness or ammonia-like tastes, particularly in cheeses aged beyond their optimal window. Tasting aged cheese at regular intervals—say, every 2–4 weeks—allows you to track flavor evolution and determine the peak moment before mold activity turns detrimental.

Practical tips for managing mold development include using breathable materials like cheese paper or waxed cloth to wrap aged cheeses, as these allow moisture exchange without trapping excess humidity. For harder cheeses, such as Parmesan, brushing the rind with brine discourages unwanted molds while promoting a protective bacterial layer. If experimenting with aging, start with small batches and document conditions to refine your process. Remember, mold is not inherently bad—it’s the steward of transformation, and mastering its role unlocks the nuanced flavors that make aged cheese a culinary treasure.

Tillamook Cheese Factory: A Tasty Road Trip from Portland

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cheese Type Differences

The aging process transforms cheese, but not all varieties follow the same trajectory. Hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano develop complex, nutty flavors and a crystalline texture after 24 months or more, making them ideal for grating. In contrast, soft cheeses such as Brie become ammoniated and unpleasantly pungent if aged beyond their 4–6 week prime. Understanding these differences is key to appreciating why age enhances some cheeses while spoiling others.

Consider the role of moisture content in aging. Semi-hard cheeses like Gruyère, aged 5–12 months, strike a balance: their moisture allows flavor development without becoming overly dry, making them perfect for melting in dishes like fondue. Meanwhile, blue cheeses such as Stilton age for 9–12 weeks, during which their veins intensify in flavor, but over-aging can lead to an overpowering bitterness. Pairing these cheeses with complementary beverages—a full-bodied red wine for Gruyère, a sweet dessert wine for Stilton—maximizes their aged profiles.

Aging also affects texture, which varies by cheese type. Hard cheeses become crumbly and granular, while semi-soft cheeses like aged Gouda develop a chewy, caramelized interior. For home aging, store hard cheeses in a cool (50–55°F), humid environment, wrapping them in wax paper to allow breathability. Soft cheeses, however, require higher humidity (around 90%) and should be aged in a cheese cave or specialized fridge drawer to prevent mold overgrowth.

Finally, the aging timeline differs drastically by type. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella are meant to be consumed within days, while a 10-year-old cheddar can command a premium for its sharp, complex flavor. When experimenting with aged cheeses, start with younger versions (3–6 months) to develop a baseline, then progress to older varieties (12+ months) to discern nuanced differences. This methodical approach ensures you appreciate the unique qualities age brings to each cheese type.

Unveiling the Mystery: Who is the Gray Man in 'I Am the Cheese'?

You may want to see also

Storage Conditions Matter

The age-old question of whether old cheese tastes better hinges significantly on how it’s stored. Proper storage isn’t just about preserving cheese; it’s about guiding its transformation. Temperature, humidity, and wrapping methods act as silent chefs, shaping flavor, texture, and aroma over time. A wheel of cheddar aged in a damp, cool cave will develop a sharper tang and crumbly texture, while the same cheese stored in a dry, warm pantry might turn bitter and hard. Storage conditions dictate whether age becomes a virtue or a flaw.

Consider the ideal environment for aging cheese: a temperature range of 50–55°F (10–13°C) and humidity between 80–85%. These conditions mimic traditional cheese caves, allowing beneficial molds and bacteria to work slowly and harmoniously. For home storage, a wine fridge or the lower shelf of a standard refrigerator (the least cold spot) paired with a humidity-controlled container, like a wooden box lined with parchment, can approximate these conditions. Avoid plastic wrap, which traps moisture and stifles the cheese’s breathability; opt for wax paper or cheese paper instead.

Contrast this with common mistakes: storing cheese in the fridge’s warmest zone (the door) or using airtight containers. The former exposes cheese to temperature fluctuations, halting or unevenly accelerating aging, while the latter creates a breeding ground for ammonia-like off-flavors. Hard cheeses like Parmesan can withstand colder temperatures, but softer varieties like Brie require gentler handling. Even the orientation matters—always store cheese upright to prevent moisture from pooling and causing spoilage.

The takeaway is clear: storage isn’t passive; it’s an active participant in the cheese’s journey. A well-stored cheese will develop complexity—nutty, earthy, or fruity notes—while a poorly stored one may turn rancid or dry. Think of storage as a recipe: precise measurements (temperature, humidity) and techniques (wrapping, placement) yield a masterpiece. Whether you’re aging a wheel for months or keeping a wedge fresh for weeks, the right conditions ensure that time enhances, not diminishes, the cheese’s character.

Chucky Cheese Games: Unlocking the Points System for Maximum Fun

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It depends on the type of cheese. Aged cheeses, like Parmesan or Cheddar, often develop deeper, more complex flavors over time, which many people prefer. However, fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta are typically enjoyed for their mild, creamy qualities and are not meant to be aged.

Aging cheese allows enzymes and bacteria to break down proteins and fats, creating new flavor compounds. This process results in a stronger, nuttier, or sharper taste, as well as a firmer texture. The longer the cheese ages, the more pronounced these characteristics become.

Yes, cheese can become over-aged, leading to an overly dry, crumbly texture and an unpleasantly bitter or ammonia-like flavor. Proper storage and knowing the ideal aging time for each type of cheese are key to ensuring it reaches its peak flavor without going too far.