The origins of cheese are deeply rooted in ancient history, with evidence suggesting that cheese-making practices date back over 7,000 years. It is widely believed that cheese originated in the fertile regions of the Middle East, particularly in what is now modern-day Iraq, Iran, and Turkey. Early evidence of cheese production has been found in archaeological sites, including remnants of cheese strainers and pottery with milk residues. The process likely began as a method of preserving milk, as early herders discovered that curdling milk and separating the solids from the whey created a more durable and transportable food source. Over time, this rudimentary practice evolved into the diverse and sophisticated cheese-making techniques we know today, spreading across continents and cultures, shaping culinary traditions worldwide.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ancient Cheese Origins: Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Fertile Crescent

- European Cheese Development: Roman Empire and monastic traditions

- Asian Cheese History: India, Tibet, and Central Asia

- American Cheese Beginnings: Indigenous practices and colonial influences

- African Cheese Traditions: North African and Sub-Saharan methods

Ancient Cheese Origins: Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Fertile Crescent

The earliest evidence of cheese production points to Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Fertile Crescent as the cradle of this ancient craft. Around 8000 BCE, these regions were already experimenting with dairy preservation, likely through the natural curdling of milk in animal stomachs used as containers. This accidental discovery laid the foundation for intentional cheese-making, as early herders recognized the value of transforming perishable milk into a more durable food source. Archaeological findings, such as sieves and pottery with residue, suggest that by 3500 BCE, cheese was a staple in these societies, integral to their diets and cultural practices.

In Mesopotamia, the fertile land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, cheese-making was intertwined with agricultural advancements. As one of the first civilizations to domesticate animals like goats and sheep, Mesopotamians had ample access to milk. Their innovation in pottery allowed for the creation of specialized vessels for curdling and straining milk, a process detailed in cuneiform tablets. These early cheeses were likely soft and fresh, consumed quickly due to the lack of refrigeration. To replicate this ancient practice, try heating milk with a natural acid like lemon juice or vinegar, then straining the curds through a fine cloth—a simple method that mirrors their techniques.

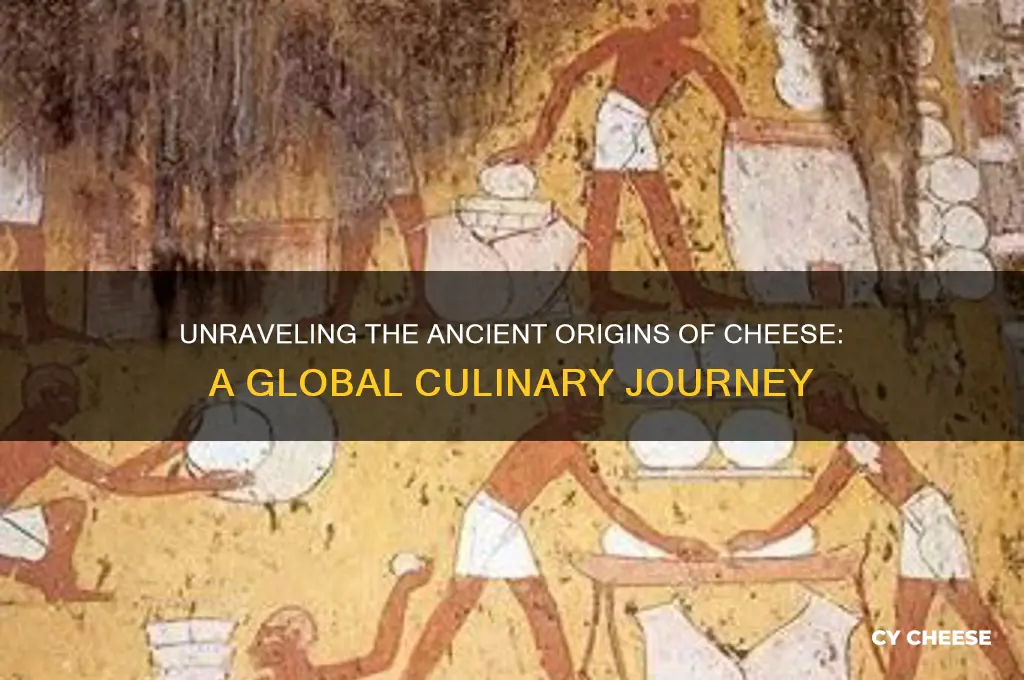

Egypt, with its arid climate and reliance on the Nile, took cheese-making to new heights. By 3000 BCE, Egyptians were producing a variety of cheeses, some of which were preserved for religious offerings or burial provisions. Murals in tombs depict dairy processing, and cheese was considered a luxury, often reserved for the elite and the gods. One notable example is the discovery of cheese remnants in the tomb of Ptahmes, a high-ranking official, dating back to 1200 BCE. For a taste of ancient Egypt, experiment with aging fresh cheese in a cool, dry place for several weeks, mimicking their natural preservation methods.

The Fertile Crescent, encompassing modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Israel, was a melting pot of dairy innovation. Here, diverse cultures shared techniques, leading to the development of harder, more complex cheeses. Shepherds in this region likely carried milk in animal stomachs, which contained rennet—a natural enzyme that accelerates curdling. This method produced firmer cheeses, ideal for long journeys and trade. To recreate this, use rennet in your cheese-making process, allowing the curds to set longer before pressing and aging.

While these ancient civilizations laid the groundwork for cheese-making, their legacy is evident in modern practices. From the accidental curdling of milk to the intentional use of enzymes and pottery, their innovations transformed dairy into a global staple. By exploring these historical methods, we not only honor their ingenuity but also gain a deeper appreciation for the craft. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced cheese maker, incorporating these ancient techniques can add a timeless dimension to your creations.

Should Cheese Babka Be Refrigerated? Storage Tips for Freshness

You may want to see also

European Cheese Development: Roman Empire and monastic traditions

The Roman Empire's influence on European cheese development cannot be overstated. Roman soldiers, acting as unwitting cheese ambassadors, carried their dairy traditions across the continent. Their military campaigns introduced techniques like rennet coagulation and pressed curd methods to regions as far as Britain and Germany. This dissemination laid the groundwork for diverse regional cheese varieties, many of which still bear the imprint of Roman ingenuity. For instance, the ancient Roman *caseus* likely evolved into the hard, aged cheeses like Pecorino Romano, still produced in Italy today.

Monastic traditions, emerging in the post-Roman era, became the guardians and innovators of cheese craftsmanship. Monasteries, often self-sufficient communities, relied on cheese as a staple food due to its long shelf life and nutritional value. Monks meticulously documented and refined cheese-making processes, experimenting with local milk sources, molds, and aging techniques. Their contributions are evident in the survival of cheeses like Trappist, produced by Cistercian monks, and the blue-veined cheeses rumored to have originated from accidental mold exposure in monastic cellars.

A comparative analysis reveals the distinct roles of the Roman Empire and monastic traditions in cheese development. While the Romans focused on standardization and spread, monks emphasized localization and refinement. The Romans brought uniformity to cheese-making practices, whereas monasteries adapted these methods to suit regional climates and resources. This interplay between imperial expansion and monastic preservation created a rich tapestry of European cheese diversity, from the creamy French Brie to the sharp English Cheddar.

To appreciate this legacy, consider a practical exercise: visit a local cheese shop and inquire about the origins of their European selections. Look for Roman-influenced hard cheeses and monastic-style soft or blue varieties. Pair a Pecorino Romano with a Trappist cheese to taste the historical continuum. This sensory exploration not only deepens your understanding of cheese history but also connects you to centuries-old traditions that shaped European culinary culture.

In conclusion, the Roman Empire and monastic traditions form the twin pillars of European cheese development. Their combined efforts—one expansive and the other introspective—created a foundation upon which modern cheese-making thrives. By studying their contributions, we gain not just historical insight but also a deeper appreciation for the artistry and science behind every wheel, wedge, and slice of cheese.

Should Brazilian Cheese Bread Be Refrigerated? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Asian Cheese History: India, Tibet, and Central Asia

Cheese production in Asia, particularly in India, Tibet, and Central Asia, predates many Western narratives, with evidence suggesting that these regions independently developed dairy fermentation techniques thousands of years ago. Archaeological findings in the Indus Valley Civilization (modern-day India and Pakistan) reveal pottery sieves and residues dating back to 2500 BCE, indicating early cheese-making practices. Unlike European methods, which often rely on rennet, Asian cheese-making traditionally employs acidification through buttermilk or yogurt cultures, resulting in softer, more perishable cheeses. This distinction highlights a unique evolutionary path in dairy technology.

In Tibet, the staple cheese *chura* exemplifies how geography and climate shape culinary traditions. Made from yak milk, *chura* is a hard, long-lasting cheese ideal for the harsh, high-altitude environment. Tibetans consume it in various forms—sliced, powdered, or brewed into *churpee tea*—demonstrating its versatility. The reliance on yak milk, rather than cow or goat milk, underscores the adaptation of cheese-making to local resources. For those interested in recreating *chura*, start by heating yak milk (or a substitute like buffalo milk) with buttermilk, then strain and press the curds until firm.

Central Asia’s cheese heritage, particularly in regions like Mongolia and Kazakhstan, revolves around *byaslag* and *kurut*, air-dried cheeses that serve as portable, nutrient-dense foods for nomadic lifestyles. These cheeses are often made from mare’s or camel’s milk, reflecting the region’s pastoral traditions. Modern enthusiasts can replicate *kurut* by simmering milk with vinegar or lemon juice, draining the whey, and sun-drying the curds into small balls. This method not only preserves the milk but also concentrates its protein and fat content, making it an efficient energy source for travelers.

India’s cheese history is deeply intertwined with religious and cultural practices. *Paneer*, a fresh, unsalted cheese, is a cornerstone of vegetarian cuisine, particularly in Hindu communities. Its simplicity—made by curdling milk with lemon juice or vinegar and pressing the curds—has ensured its widespread adoption. For optimal results, use full-fat milk and avoid over-pressing to maintain paneer’s crumbly texture. Pair it with spices like cumin or coriander for traditional dishes like *palak paneer* or *mattar paneer*.

Comparing these Asian cheese traditions reveals a common thread: innovation driven by necessity. Whether adapting to high altitudes, nomadic life, or dietary restrictions, each region developed techniques suited to its environment. For modern cooks, exploring these cheeses offers not only a taste of history but also practical solutions for preserving dairy without refrigeration. Experimenting with traditional methods—like acidification or sun-drying—can yield unique flavors and textures, bridging ancient practices with contemporary kitchens.

Discover the Best Cotija Cheese Substitutes for Your Recipes

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.99 $14.99

American Cheese Beginnings: Indigenous practices and colonial influences

The origins of American cheese are deeply rooted in the intersection of Indigenous practices and colonial influences, a story often overshadowed by the dominance of European cheesemaking traditions. Long before European settlers arrived, Indigenous peoples across the Americas were already preserving milk in various forms, though not in the solidified, aged manner we typically associate with cheese today. These early practices laid the groundwork for what would become a uniquely American cheese culture.

Indigenous communities, particularly in Central and South America, utilized milk from domesticated animals like llamas and alpacas, as well as from wild sources, to create fermented dairy products. For instance, the Quechua people of the Andes produced *qori*, a thickened milk product similar to yogurt, which was a precursor to more complex dairy preservation methods. These practices were not just about sustenance but also about cultural expression, often tied to rituals and communal sharing. While these early forms were not cheese in the modern sense, they demonstrated an understanding of milk transformation that would later merge with colonial techniques.

The arrival of European colonists in the 16th and 17th centuries introduced new animals, such as cows and goats, and more advanced cheesemaking methods. However, the adaptation of these techniques was not seamless. Early colonial attempts at cheesemaking often failed due to unfamiliarity with local climates and resources. It was the blending of Indigenous knowledge—such as the use of natural coagulants and fermentation processes—with European methods that eventually led to the development of distinct American cheeses. For example, the first recorded American cheese, produced in the late 17th century, was likely a simple, unaged variety made by combining Indigenous preservation techniques with European recipes.

One of the most significant early examples of this fusion is the creation of "American cheddar," which emerged in the 18th century. While cheddar itself is of British origin, the American version was shaped by local conditions and ingenuity. Farmers in New England and the Mid-Atlantic adapted the recipe to suit their climates, using locally available ingredients and Indigenous-inspired methods of preservation. This cheese became a staple in colonial households and later a symbol of American agricultural self-sufficiency.

The legacy of Indigenous practices in American cheese is often overlooked, but their influence persists in the emphasis on locality, sustainability, and innovation. Today, artisanal cheesemakers across the U.S. are revisiting these historical roots, incorporating native ingredients like sumac or maple into their recipes and reviving traditional methods. By acknowledging this blended heritage, we not only honor the past but also pave the way for a more diverse and authentic American cheese culture. Practical steps for enthusiasts include exploring regional cheeses, supporting Indigenous-owned dairies, and experimenting with historical recipes to connect with this rich, layered history.

Perfectly Packed: Tips for Cheese and Crackers Lunch Prep

You may want to see also

African Cheese Traditions: North African and Sub-Saharan methods

Cheese, often associated with European culinary traditions, has a lesser-known but equally fascinating history in Africa. While the origins of cheese are commonly traced to the Middle East and Europe, African cheese traditions, particularly in North Africa and Sub-Saharan regions, reveal a unique and diverse heritage. These methods, shaped by local climates, resources, and cultural practices, offer a fresh perspective on the global story of cheese.

In North Africa, particularly in countries like Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, cheese-making is deeply rooted in Berber traditions. One standout example is *jben*, a soft, fresh cheese made from cow’s or goat’s milk. The process is simple yet precise: milk is heated, curdled with rennet or lemon juice, and then drained in a cloth. The result is a mild, slightly tangy cheese often paired with honey, olive oil, or bread. This method reflects the region’s emphasis on preserving freshness and utilizing readily available ingredients. Unlike aged European cheeses, *jben* is consumed within days of production, aligning with the arid climate where long-term storage is challenging.

Sub-Saharan Africa, with its diverse ecosystems, showcases even more varied cheese traditions. In countries like Ethiopia and Kenya, *ayib* (Ethiopia) and *muruku* (Kenya) are prime examples. *Ayib* is made by fermenting milk naturally, often in a calabash gourd, until it separates into curds and whey. The curds are then strained and sometimes mixed with spices like coriander or chili. This method relies on lactic acid bacteria, which thrive in the warm climate, to curdle the milk. Similarly, *muruku* in Kenya is made by boiling milk, adding a souring agent like vinegar, and straining the curds. These techniques highlight resourcefulness, using fermentation and natural souring agents in the absence of commercial rennet.

A comparative analysis reveals that African cheese traditions prioritize simplicity, sustainability, and adaptability. Unlike industrialized cheese production, these methods are often practiced at a household level, passed down through generations. For instance, in rural Sub-Saharan communities, women play a central role in cheese-making, integrating it into daily routines. This contrasts with the specialized, large-scale production seen in Europe. Additionally, African cheeses are typically fresh and consumed quickly, reflecting a focus on immediate utility rather than long-term preservation.

To explore these traditions at home, start with *jben*: heat 1 liter of milk to 30°C, add 2 tablespoons of lemon juice, stir until curds form, and drain in cheesecloth for 2 hours. For *ayib*, leave 1 liter of milk at room temperature for 24 hours, stir occasionally, and strain the curds. These recipes require minimal equipment and ingredients, making them accessible. When experimenting, consider the climate: warmer temperatures accelerate fermentation, so adjust timing accordingly. By engaging with these methods, you not only create authentic African cheeses but also connect with a rich cultural heritage that challenges conventional narratives about cheese origins.

Cheesing Offerings in D2: Strategies for Efficient Farming

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, evidence suggests that cheese-making dates back to ancient Egypt, with depictions of cheese-making processes found in Egyptian tomb murals around 2000 BCE.

While ancient Egypt has strong evidence, some historians believe cheese-making may have also originated independently in Mesopotamia around the same time, as early as 3000 BCE.

No, cheese did not originate in Europe. However, European regions like France, Italy, and Switzerland significantly refined and diversified cheese-making techniques, leading to many iconic varieties we know today.

![QUESO!: Regional Recipes for the World's Favorite Chile-Cheese Dip [A Cookbook]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91YLsuAZ1xL._AC_UY218_.jpg)