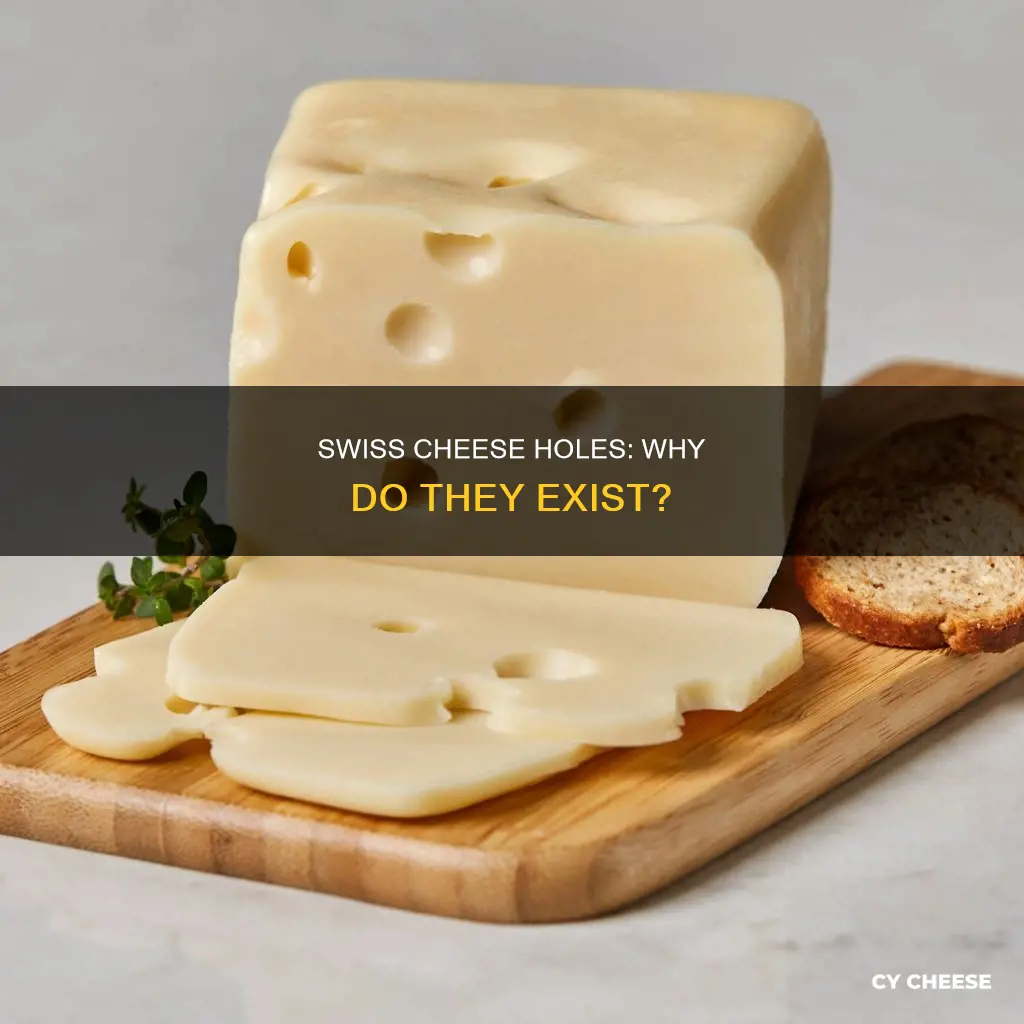

Swiss cheese is known for its distinctive holes, often called eyes. These holes are created during the cheese-making process, specifically by bacteria cultures that produce carbon dioxide gas, forming air pockets within the cheese. The size of the holes can vary depending on the type of bacteria and cheese-making techniques. Interestingly, the holes in Swiss cheese have become less common and smaller in recent years due to modern milking methods that prevent hay particles from falling into the milk buckets, which was previously believed to cause the holes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reason for holes | Caused by flecks of hay in the milk, which create weaknesses in the structure of the curd, allowing gas to form and create holes |

| Hole size | Vary from dime-sized to quarter-sized |

| Hole type | Carbon dioxide bubbles |

| Hole formation | During the cheese-making process, specifically due to the role of microbes |

| Hole-causing bacteria | Propionibacterium freudenrichii subspecies shermanii |

| Hole-causing bacteria characteristics | Microscopic, gram-positive, non-motile |

| Hole-causing bacteria function | Consume lactic acid and produce carbon dioxide |

| Hole occurrence | More common in the past due to traditional cheese-making methods; modern methods reduce the likelihood of hay falling into milk |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Caused by carbon dioxide bubbles

The holes in Swiss cheese, also called "eyes", are caused by carbon dioxide bubbles. This occurs when certain bacteria, namely Propionibacterium freudenreichii, feast on the lactic acid left behind by other bacteria in the warm, humid caves where the cheese wheels are aged. As the bacteria digest the lactic acid, they release carbon dioxide gas, which forms bubbles as it tries to escape the dense cheese. These bubbles get trapped as the cheese matures, resulting in the characteristic holes in Swiss cheese.

The size and number of holes can vary depending on the presence of particles such as hay or dust in the milk, which provide nucleation sites for the carbon dioxide bubbles to form. In recent years, the holes in Swiss cheese have become smaller or less frequent due to modern milk extraction methods, which ensure cleaner milk with fewer particles.

The process of hole formation in Swiss cheese was a subject of scientific inquiry for many years. A popular scientific belief attributed the holes to carbon dioxide released by bacteria. However, in 2015, a Swiss agricultural institute called Agroscope proposed a different theory. They suggested that the holes were created by microscopically small hay particles falling into the buckets collecting milk, causing weaknesses in the structure of the curd where gas could form and create holes.

The presence of carbon dioxide-producing bacteria, along with the availability of nucleation sites, influences the development of eyes in Swiss cheese. The interaction between these factors results in the unique characteristics of each batch of cheese, contributing to the playful look and airy, elastic texture associated with Swiss cheese.

In summary, the holes in Swiss cheese are indeed caused by carbon dioxide bubbles, but the formation of these bubbles is influenced by a combination of microbial activity and the presence of particles in the milk. The size and number of holes can vary, and modern milk extraction methods have led to changes in the prevalence and size of holes in Swiss cheese over time.

Swiss Cheese and Cholesterol: What's the Truth?

You may want to see also

Hay particles in milk

The presence of hay particles in milk is the reason behind the holes in Swiss cheese. This phenomenon has intrigued scientists for a long time, and in 2015, researchers from the Agroscope Institute for Food Sciences and the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology finally solved the mystery.

Swiss cheese, known for its distinctive holes, or "eyes," has long been a subject of curiosity. Initially, it was believed that the holes were caused by bacteria or even mice nibbling on the cheese. However, the true origin of these holes lies in the cheese-making process and the presence of hay particles in the milk.

The traditional method of cheese-making involved collecting milk in open buckets, often in barns. Microscopically small hay particles would fall into these buckets, and as the milk matured into cheese, these particles would develop into bigger holes. This process is specific to certain Swiss cheeses, such as Emmental and Appenzell.

The researchers from Agroscope confirmed this by conducting experiments where they added different amounts of hay dust to the milk. They discovered that they could regulate the number of holes in the resulting cheese. Additionally, they observed the cheese's ripening process over 130 days using computed tomography (CT) scans to study the formation of holes.

In recent years, the number of holes in Swiss cheese has decreased due to modern milking methods. Sealed milking machines have replaced open buckets, reducing the likelihood of hay particles contaminating the milk. This change in the cheese-making process has resulted in fewer and smaller holes in Swiss cheese.

While cleaner milk production processes are generally beneficial for food safety, they have inadvertently reduced the number of holes in Swiss cheese. This discovery has provided valuable insights into the traditional cheese-making process and the role of hay particles in creating the unique characteristics of Swiss cheese.

Rennet in Swiss Cheese: What's the Truth?

You may want to see also

Bacteria in milk

Milk is a suitable medium for bacterial growth, and pathogenic bacteria in milk pose a serious health threat to humans, constituting about 90% of all dairy-related diseases. The bacteria present in raw milk can come from infected udder tissues (e.g., mastitis-causing bacteria), the dairy environment (e.g., soil, water, and cow manure), and milking equipment. High bacteria counts in raw milk indicate poor animal health and poor farm hygiene.

Raw milk advocates claim that raw milk does not cause lactose intolerance because it contains lactase, secreted by "beneficial" or probiotic bacteria present in raw milk. However, the FDA states that raw milk does not contain probiotic organisms. Fermented dairy products, especially yogurt, have been reported to ease lactose malabsorption in lactose-intolerant subjects. This enhanced digestion of lactose has been attributed to the hydrolysis of lactose by lactase secreted by yogurt fermentation microorganisms.

Raw milk can host various human pathogens, including E. coli, Salmonella, Streptococcus spp., Yersinia enterocolitica, Campylobacter jejuni, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Coxiella burnetii, to name a few. Probiotic microorganisms must be non-pathogenic and of human origin to have a positive impact on human health. An example of a human pathogen that can be transmitted to humans through raw milk is Streptococcus pyogenes, which can cause strep throat.

The safety of raw milk is a controversial topic, with passionate advocates on both sides of the argument. Public health officials, including the CDC, warn of the potential dangers of milk that has not been pasteurized to kill bacteria and other microbes. Advocates of raw milk argue that modern dairy practices have mitigated these risks and that pasteurization removes vital nutrients from the milk. They also point to the numerous precautions taken by modern dairy farmers who produce and sell raw milk, such as maintaining animal health, hygienic milking conditions, safety practices during packaging and transport, and extensive testing for bacteria. However, the CDC notes that testing does not always detect low levels of microbial contamination, which can still cause illness.

Swiss Cheese and Dairy: What's the Deal?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Modern milking methods

Machine Milking

Machine milking, also known as vacuum milking, represents a significant advancement in modern animal husbandry. This method employs vacuum systems to gently squeeze the udders and extract milk. The machine's design aims to create a pleasant experience for the cows while ensuring udder health. Vacuum systems offer a faster and more efficient milking process, reducing the labour intensity associated with traditional hand milking.

Automatic Milking Systems (AMS) or Voluntary Milking Systems (VMS)

AMS or VMS are revolutionary technologies that fully automate the milking process. These systems, also referred to as robotic milking, have been commercially available since the early 1990s. They utilise computers and specialised herd management software to monitor the health status of cows and optimise the milking routine. One of the key advantages of AMS is that they allow cows to decide their own milking time and interval, enhancing flexibility and individual care.

Modern Milking Machines

Modern milking machines are designed with precision and efficiency in mind. They aim to remove up to 95% of available milk without relying on additional cluster weight or manual assistance. These machines are meticulously cleaned and maintained, ensuring strict adherence to manufacturer instructions. The process involves careful cluster attachment, vacuum application, and teat canal opening, all while maintaining udder health and comfort.

Hygiene and Health Considerations

Selective Breeding and Lactation Management

Dairy farmers employ selective breeding and control of reproduction, nutrition, and disease management to maximise milk production. By influencing lactation, they can increase milk secretion and take advantage of the cow's secretion potential. This involves understanding the different feeding practices during early, mid, and late lactation stages to optimise milk output.

Swiss Cheese: Fattening or Healthy?

You may want to see also

Size of holes varies

The size of holes in Swiss cheese varies across different varieties of the cheese. For example, Jarlsberg is known for its medium-sized holes, while Appenzeller is characterised by larger holes.

The size of the holes is also influenced by the presence of hay particles in the milk used to make the cheese. Microscopically small hay particles can fall into buckets of milk during the collection process, creating weaknesses in the structure of the curd as the cheese matures. This allows gas to form and expand, resulting in larger holes.

The type of bacteria present in the cheese-making process also contributes to the size variation of the holes. A specific bacterial strain, Propionibacterium freudenrichii subspecies shermanii, converts milk into carbon dioxide at a warm temperature of 70°F. As the cheese cools, the carbon dioxide gas forms air pockets of varying sizes within the cheese.

Additionally, modern milk extraction methods have reduced the occurrence and size of holes in Swiss cheese. Traditional cheese-making practices, such as using open buckets, increased the likelihood of hay particles contaminating the milk and creating larger holes. Today, more hygienic and controlled milk collection processes have minimised the presence of hay, resulting in smaller or nonexistent holes in Swiss cheese.

Swiss Cheese Cubes: Sam's Club's Best-Kept Secret

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The holes in Swiss cheese, also known as "eyes", are caused by carbon dioxide bubbles that form in the cheese during the cheese-making process. Specifically, they are caused by a bacteria called Propionibacterium freudenrichii subspecies shermanii, or "Props", which gets added to the cheese.

In recent years, the holes in Swiss cheese have become smaller or do not appear at all. This is because milk for cheese-making is now usually extracted using modern methods, making it less likely for hay particles to contaminate the milk and create holes.

Hay particles create weaknesses in the structure of the curd, allowing gas to form and create holes. The bacteria in the cheese produce carbon dioxide, creating air bubbles that leave holes when the cheese cools.

No, the size of the holes does not affect the taste of the cheese. However, the size of the holes can be controlled through temperature, storage time, and acidity levels.