Cheese, one of the world’s oldest and most beloved foods, has a history that dates back thousands of years, likely originating in the Middle East around 8000 BCE. Early evidence suggests that cheese-making began as a way to preserve milk, with ancient herders discovering that curdling milk and separating the solids from the whey created a longer-lasting, portable food source. The process was likely accidental, possibly involving the use of animal stomachs, which contain rennet, a natural enzyme that coagulates milk. Over time, cheese-making techniques spread across Europe, Asia, and beyond, evolving into the diverse array of styles and flavors we enjoy today. Its origins are deeply intertwined with human ingenuity, the domestication of animals, and the need for sustainable food preservation in ancient societies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin Time Period | Cheese-making likely originated around 8000-3000 BCE. |

| Geographical Origin | Middle East, particularly in regions like Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt. |

| Discovery Method | Accidental discovery through the natural curdling of milk in animal skins. |

| Early Evidence | Archaeological findings suggest cheese-making in Poland around 5500 BCE. |

| Purpose of Invention | Preservation of milk for longer periods in the absence of refrigeration. |

| Key Ingredients | Milk (from sheep, goats, or cows), rennet (or natural acids for curdling). |

| Early Techniques | Using animal stomachs as containers, which contained rennet for curdling. |

| Cultural Spread | Spread through trade routes and migrations across Europe, Asia, and beyond. |

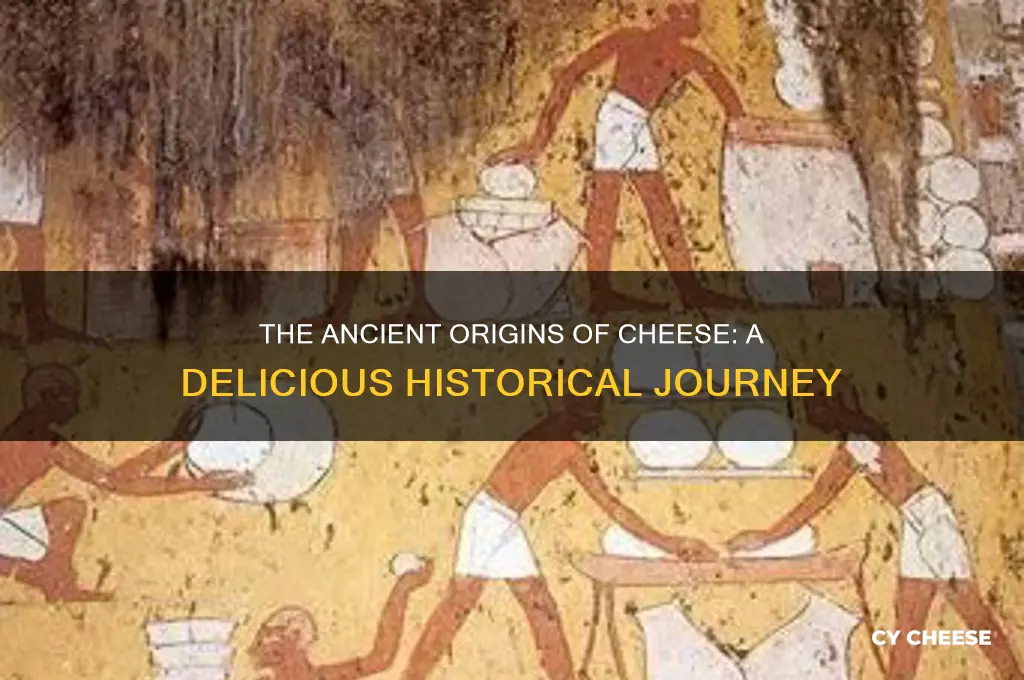

| Historical Records | Mentioned in ancient texts like Homer's Odyssey and Egyptian tomb murals. |

| Evolution of Varieties | Diversified over centuries with regional variations in ingredients and methods. |

| Modern Developments | Industrialization in the 19th century standardized and mass-produced cheese. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ancient Cheese Making: Evidence suggests cheese production dates back over 7,000 years to ancient civilizations

- Accidental Discovery: Cheese likely originated from stored milk curdling naturally due to bacteria and rennet

- Early Techniques: Ancient methods involved using animal stomachs as containers to separate curds and whey

- Regional Variations: Different cultures developed unique cheese types based on local milk sources and climates

- Historical Spread: Trade routes and migrations helped cheese-making techniques spread across continents over centuries

Ancient Cheese Making: Evidence suggests cheese production dates back over 7,000 years to ancient civilizations

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, has a history as rich and complex as its flavors. Evidence suggests that cheese production dates back over 7,000 years, rooted in the practices of ancient civilizations. Archaeological findings, such as strainers with milk fat residues from Poland’s Kujawy region, indicate that as early as 5,500 BCE, humans were experimenting with curdling milk. This discovery challenges the notion that cheese-making began in the Middle East, pointing instead to Europe’s Neolithic communities. These early cheese-makers likely used animal stomachs, which contain rennet, to coagulate milk, a technique still employed in traditional cheese production today.

The process of ancient cheese-making was both practical and innovative. Early herders noticed that storing milk in containers made from animal stomachs caused it to separate into curds and whey. This accidental discovery not only preserved milk but also created a more portable and longer-lasting food source. For nomadic communities, cheese became a vital part of their diet, providing essential nutrients like protein and fat. Over time, these rudimentary methods evolved as cultures experimented with different milks (goat, sheep, cow) and techniques, laying the foundation for the diverse cheese varieties we enjoy today.

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for ancient cheese-making comes from Egypt. Hieroglyphs and tomb paintings from around 2,000 BCE depict cheese-making processes, including the use of sieves and molds. Egyptian cheese, often made from sheep or goat milk, was a luxury item, reserved for the elite and used in religious offerings. In contrast, Mesopotamian texts from the same period mention cheese as a common food, suggesting its widespread consumption across social classes. These regional differences highlight how cheese-making adapted to local cultures, climates, and resources.

To recreate ancient cheese at home, start with raw milk and an acid like lemon juice or vinegar, or use rennet for a more authentic approach. Heat the milk to around 30°C (86°F), add the coagulant, and let it curdle. Once separated, drain the whey and press the curds to form a simple cheese. For a historical touch, use a cloth or animal-skin strainer, though modern cheesecloth works just as well. This hands-on process not only connects you to millennia-old traditions but also offers a deeper appreciation for the craftsmanship behind every wheel of cheese.

The legacy of ancient cheese-making is evident in the global cheese industry today. From the crumbly feta of Greece to the creamy brie of France, each variety traces its roots to these early innovations. Modern techniques may have refined the process, but the core principles remain unchanged. As we savor a slice of cheese, we’re not just tasting a food product—we’re experiencing a piece of human history, preserved through 7,000 years of ingenuity and adaptation.

Do All Danish Pastries Have Cheese? Unraveling the Danish Delicacy Myth

You may want to see also

Accidental Discovery: Cheese likely originated from stored milk curdling naturally due to bacteria and rennet

The story of cheese begins with a simple, yet transformative accident. Imagine early humans storing milk in containers made from animal stomachs, a practice likely adopted for its practicality. Unbeknownst to them, these stomachs contained rennet, an enzyme that, when combined with naturally occurring bacteria, causes milk to curdle. This unintended chemical reaction turned liquid milk into a solid, edible mass—the precursor to cheese. This accidental discovery highlights how necessity and serendipity often drive culinary innovation.

To replicate this process today, start by understanding the key components. Milk, bacteria, and rennet are the trifecta of cheese-making. For a basic experiment, use unpasteurized milk (as pasteurization kills beneficial bacteria) and add a small amount of rennet (about 1 drop per quart of milk). Allow the mixture to sit at room temperature (around 72°F or 22°C) for 12–24 hours. The bacteria will ferment the lactose, acidifying the milk, while the rennet coaxes it to curdle. The result? A rudimentary form of cheese, similar to what our ancestors might have stumbled upon.

This accidental method contrasts sharply with modern, controlled cheese-making techniques. Today, specific strains of bacteria and precise rennet dosages are used to ensure consistency. However, the core principle remains the same: curdling milk through bacterial action and enzymatic reaction. The takeaway? Cheese’s origins remind us that even the most sophisticated foods can trace their roots to simple, unintended experiments.

Practical tip: If you’re curious to try this at home, source raw milk from a trusted supplier and handle it with care. Alternatively, use store-bought buttermilk as a starter culture to introduce bacteria. While the result won’t be identical to ancient cheese, it offers a tangible connection to the accidental discovery that changed culinary history. This hands-on approach not only deepens appreciation for cheese but also underscores the role of chance in shaping our diets.

Measuring Cheese: How Many Tablespoons Are in a Pound?

You may want to see also

Early Techniques: Ancient methods involved using animal stomachs as containers to separate curds and whey

The origins of cheese are deeply rooted in the accidental discovery of curdling milk, a process that likely began over 8,000 years ago. Early humans, storing milk in containers made from animal stomachs, noticed that the natural enzymes in these stomach linings caused the milk to separate into curds and whey. This simple yet transformative observation laid the foundation for one of humanity's most enduring foods. The use of animal stomachs as containers was not merely a coincidence but a practical solution born from the materials available at the time.

To replicate this ancient technique, one would need a fresh animal stomach, preferably from a ruminant like a sheep or goat, which contains rennet—a complex of enzymes essential for coagulation. First, clean the stomach thoroughly, removing any residual contents and rinsing it with water. Next, pour fresh milk into the stomach and seal it, allowing the mixture to sit in a warm environment for several hours. The rennet in the stomach lining will activate, causing the milk to curdle and separate into solid curds and liquid whey. This method, though rudimentary, is remarkably effective and highlights the ingenuity of early cheesemakers.

Comparing this ancient technique to modern cheesemaking reveals both continuity and evolution. Today, rennet is often derived from microbial or plant sources, and stainless steel vats have replaced animal stomachs. However, the core principle remains the same: coagulating milk to separate curds and whey. The ancient method, while time-consuming and labor-intensive, offers a tangible connection to the past and a deeper appreciation for the craftsmanship involved in cheese production. It also underscores the resourcefulness of early humans, who turned a simple observation into a culinary revolution.

Practically, attempting this technique today can serve as an educational experiment rather than a primary method of cheesemaking. For those interested, sourcing a fresh animal stomach may require contacting local farmers or butchers. It’s crucial to handle the stomach with care, ensuring it remains clean and free from contaminants. While the resulting cheese may lack the refinement of modern varieties, the process provides invaluable insight into the origins of this beloved food. By revisiting these ancient methods, we not only honor the ingenuity of our ancestors but also gain a deeper understanding of the science and art behind cheese.

Why Fast Food Burgers Always Include Cheese: A Melty Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.99 $14.99

Regional Variations: Different cultures developed unique cheese types based on local milk sources and climates

The diversity of cheese is a testament to human ingenuity and adaptation, as each region’s unique environmental conditions and cultural practices have shaped distinct cheese varieties. Consider the Alps, where harsh winters and limited resources led to the creation of hard, long-lasting cheeses like Gruyère and Emmental. These cheeses were designed to preserve milk’s nutritional value through the cold months, utilizing cow’s milk, which was abundant in the region. The high altitude and cool climate slowed bacterial activity, allowing for slower aging and the development of complex flavors. This example illustrates how geography and necessity converge to create culinary staples.

In contrast, the Mediterranean’s warm, dry climate fostered the rise of soft, brined cheeses such as feta and halloumi. Sheep and goat milk, more common in these areas due to the animals’ adaptability to sparse vegetation, became the primary ingredients. The brining process not only preserved the cheese but also suited local palates accustomed to salty, tangy flavors. These cheeses often feature in regional dishes, reflecting their integration into daily life. For instance, feta’s crumbly texture and sharp taste make it a perfect pairing for Greek salads, while halloumi’s high melting point allows it to be grilled, a cooking method favored in Cyprus.

Northern Europe’s cool, damp climate gave birth to cheeses like Cheddar and Gouda, which rely on cow’s milk and specific aging techniques. Cheddar, originating in England, is known for its bandaging process, where the cheese is wrapped in cloth and aged in caves, absorbing earthy flavors. Gouda, from the Netherlands, is waxed to retain moisture in the region’s humid air. Both cheeses highlight how local climates dictate not only ingredients but also production methods. The result is a range of textures and flavors—from sharp, crumbly Cheddar to creamy, nutty Gouda—that reflect their origins.

Practical tip: When exploring regional cheeses, consider pairing them with local wines or beverages to enhance their flavors. For instance, a bold red wine complements the richness of Alpine cheeses, while a crisp white wine balances the saltiness of Mediterranean varieties. Additionally, experimenting with traditional recipes can deepen your appreciation of these cheeses’ cultural significance. For example, try making a classic French onion soup with Gruyère or a Cypriot salad with grilled halloumi to experience these cheeses in their intended contexts.

Ultimately, regional variations in cheese are a fascinating study in how humans adapt to their environments, transforming local resources into enduring culinary traditions. Each cheese tells a story of its place of origin, from the milk source to the climate’s influence on aging and flavor development. By understanding these nuances, you not only enrich your palate but also gain insight into the cultural and historical contexts that shaped these beloved foods.

Perfect Pairings: Tips for Arranging a Fruit and Cheese Tray

You may want to see also

Historical Spread: Trade routes and migrations helped cheese-making techniques spread across continents over centuries

The Silk Road, a network of trade routes connecting the East and West, wasn't just a conduit for spices and silk—it was also a highway for cheese-making knowledge. Merchants traveling between Europe and Asia inadvertently carried with them not only goods but also techniques, such as the use of rennet for curdling milk and methods for aging cheeses. For instance, the hard, aged cheeses of Central Asia, like *qurut*, likely influenced the development of Italian Pecorino and French Comté. These exchanges weren't just one-way; European methods of using molds and bacteria to create soft cheeses, such as Brie, may have traveled eastward, blending with local traditions to create unique hybrids.

Migrations played an equally pivotal role in spreading cheese-making across continents. The Mongol Empire, spanning from Eastern Europe to East Asia in the 13th century, facilitated the movement of people and their culinary practices. Nomadic tribes, who had long preserved milk as cheese for survival, introduced their techniques to settled populations. In the Americas, European colonization brought cheese-making to the New World, but it was the adaptation of these techniques to local resources—like using buffalo milk in Mexico for Oaxaca cheese—that created distinct regional varieties. This blending of old-world methods with new-world ingredients illustrates how migrations reshaped cheese traditions.

Trade routes also acted as cultural melting pots, where cheese-making evolved through cross-pollination of ideas. In the Mediterranean, Phoenician and Greek traders shared methods of salting and brining cheeses, which later influenced Roman practices. The Romans, in turn, spread these techniques across their empire, from Britain to North Africa. For example, the British cheese Cheddar traces its roots to Roman methods of draining and pressing curds. Similarly, the Byzantine Empire preserved and disseminated cheese-making knowledge during the Middle Ages, ensuring its survival and spread into Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

Practical tips for understanding this historical spread include tracing the lineage of specific cheeses. For instance, the Dutch Gouda and Swiss Emmental share similarities in their washed-rind techniques, likely due to trade between the Low Countries and Alpine regions. To explore this further, consider creating a cheese map that connects regions through their shared methods or ingredients. For example, the use of blue mold in cheeses like Roquefort and Stilton can be linked to trade routes that introduced penicillium cultures across Europe. By examining these connections, you can see how cheese-making techniques traveled, adapted, and thrived in new environments.

Finally, the historical spread of cheese-making highlights the interconnectedness of human cultures. It’s a reminder that food traditions are rarely static; they evolve through contact, conflict, and collaboration. To appreciate this legacy, try recreating ancient cheese recipes using modern tools—for example, making a basic rennet-curdled cheese with goat’s milk, as early herders might have done. This hands-on approach not only deepens your understanding of history but also connects you to a global heritage shaped by centuries of trade and migration.

Is Pork in Cheese? Unraveling the Myth and Facts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese is believed to have originated around 8000 BCE in the Middle East, likely as a result of storing milk in containers made from the stomachs of animals. The rennet in the stomach lining caused the milk to curdle, creating a primitive form of cheese.

The exact person who first discovered cheese-making is unknown, but it is thought to have been an accidental discovery by early herders in regions like Mesopotamia or ancient Egypt. The process likely evolved as people experimented with preserving milk.

Cheese-making techniques spread through trade, migration, and cultural exchanges. The Romans played a significant role in popularizing cheese across Europe, while other cultures independently developed their own methods, leading to the diverse varieties of cheese we know today.

![QUESO!: Regional Recipes for the World's Favorite Chile-Cheese Dip [A Cookbook]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91YLsuAZ1xL._AC_UY218_.jpg)