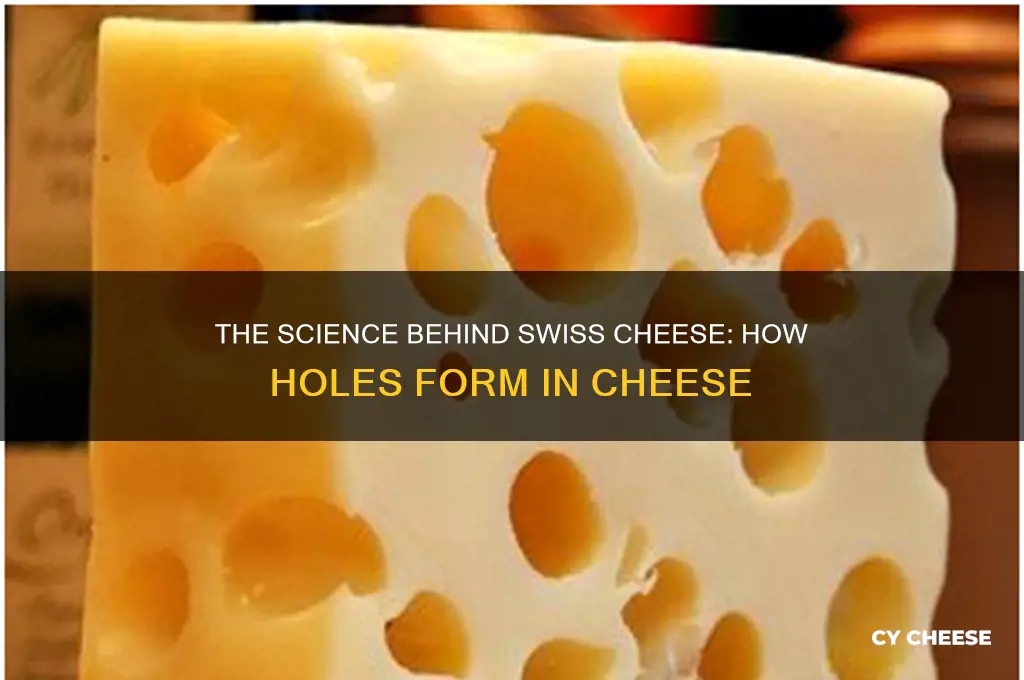

Cheese with holes, such as Swiss or Emmental, gets its distinctive appearance from a specific fermentation process involving bacteria. During cheese production, these bacteria, particularly *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, produce carbon dioxide gas as they break down lactic acid in the curd. As the cheese ages, the gas becomes trapped within the semi-solid matrix, forming small bubbles that eventually expand into the characteristic holes. The size and number of holes depend on factors like the cheese's moisture content, aging time, and the activity of the bacteria. This unique feature not only adds to the cheese's visual appeal but also influences its texture and flavor, making it a fascinating example of microbial activity in food science.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cause of Holes | Carbon dioxide gas produced by bacteria during fermentation |

| Bacteria Responsible | Propionibacterium freudenreichii (primarily), Lactobacillus spp., Streptococcus spp. |

| Gas Formation Process | Bacteria metabolize lactic acid, producing propionic acid and carbon dioxide |

| Cheese Types with Holes | Emmental, Swiss, Leerdammer, Appenzeller, Maasdam |

| Hole Size | Varies; typically 1-2 cm in diameter, but can be larger or smaller depending on cheese type and aging |

| Hole Distribution | Irregular, scattered throughout the cheese |

| Affecting Factors | Milk quality, bacterial culture, curd treatment, aging conditions (temperature, humidity) |

| Role of Starter Cultures | Specific bacterial strains are added to milk to initiate hole formation |

| Aging Time | Longer aging increases hole size and number |

| Texture Impact | Holes contribute to a lighter, more open texture |

| Flavor Impact | Propionic acid contributes a nutty, sweet flavor |

| Myth | Holes are not caused by air bubbles or mechanical processes |

| Scientific Term | "Eyes" (referring to the holes in cheese) |

| Historical Origin | First observed in Swiss cheeses, hence the term "Swiss cheese" |

| Commercial Production | Controlled conditions ensure consistent hole formation in industrial cheese-making |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Role of bacteria: Specific bacteria produce CO2 gas during fermentation, forming bubbles that become holes in cheese

- Curd stretching process: Stretching curd traps air pockets, contributing to hole formation in cheeses like Swiss

- Aging conditions: Proper humidity and temperature during aging allow gas expansion, creating larger holes

- Type of milk used: Cow's milk proteins promote better gas retention, leading to more holes in certain cheeses

- Cheese variety examples: Emmental and Gruyère are known for large holes due to specific production methods

Role of bacteria: Specific bacteria produce CO2 gas during fermentation, forming bubbles that become holes in cheese

The holes in cheese, often affectionately called "eyes," are not a random occurrence but the result of a precise biological process driven by specific bacteria. These microorganisms, primarily *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* in Swiss-type cheeses like Emmental and Gruyère, play a starring role in creating the distinctive texture we love. During the fermentation stage of cheese-making, these bacteria metabolize lactic acid, a byproduct of milk fermentation, and produce carbon dioxide (CO₂) as a waste product. This CO₂ forms tiny bubbles within the curd, which expand as the cheese ages, eventually becoming the holes we associate with these varieties.

To understand the process better, imagine a cheese wheel as a living, breathing ecosystem. The bacteria are introduced during the cheesemaking process, either naturally from the environment or through specific cultures added by the cheesemaker. As the cheese matures in a controlled environment, the bacteria thrive in the absence of oxygen, a condition known as anaerobic fermentation. The CO₂ they produce is trapped within the cheese matrix, initially as microscopic bubbles. Over time, these bubbles grow, coalesce, and become visible as the cheese structure solidifies. The size and distribution of the holes depend on factors like the bacteria’s activity level, the cheese’s moisture content, and the aging conditions.

For home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, understanding this process can help troubleshoot or even replicate hole formation. For instance, ensuring the cheese is aged at the optimal temperature (around 20–24°C or 68–75°F for Swiss-type cheeses) encourages bacterial activity. Too low a temperature slows fermentation, resulting in smaller or fewer holes, while too high a temperature can lead to uneven hole distribution. Additionally, maintaining proper humidity (around 90%) prevents the cheese from drying out, allowing the CO₂ bubbles to expand freely. If you’re experimenting with hole formation, consider using a starter culture containing *Propionibacterium* for consistent results.

Comparatively, cheeses without these specific bacteria, such as Cheddar or Mozzarella, lack the same hole formation because their fermentation processes do not produce significant CO₂. This highlights the unique role of *Propionibacterium* in creating the eyes in Swiss-type cheeses. While some cheeses may have small air pockets from other factors, the large, evenly distributed holes are a hallmark of this bacterial activity. Thus, the next time you slice into a wheel of Emmental, remember that those holes are not just a quirk but a testament to the intricate dance between microbiology and craftsmanship.

Finally, the role of bacteria in hole formation underscores the importance of precision in cheesemaking. From the initial culturing to the final aging, each step influences the bacteria’s activity and, consequently, the cheese’s texture. For those looking to master this art, patience and attention to detail are key. Monitor the cheese’s progress regularly, adjusting conditions as needed to encourage optimal bacterial growth. With time and practice, you’ll not only understand how the holes form but also appreciate the science behind one of the world’s most beloved foods.

Mastering the Art of Cutting Large Cheese Wheels: Tips & Techniques

You may want to see also

Curd stretching process: Stretching curd traps air pockets, contributing to hole formation in cheeses like Swiss

The curd stretching process, a pivotal step in crafting cheeses like Swiss, Mozzarella, and Provolone, is where the magic of hole formation begins. During this stage, the curd is heated and kneaded, a technique that not only develops texture but also traps air pockets within the cheese matrix. These air pockets, initially microscopic, expand during aging due to gas production by specific bacteria, resulting in the characteristic holes. The precision of this process—temperature, duration, and technique—dictates the size and distribution of holes, making it a delicate balance of art and science.

To execute curd stretching effectively, begin by heating the curd to 50–60°C (122–140°F), ensuring it becomes pliable without breaking. Use clean, food-grade gloves or tools to knead the curd gently, folding it over itself repeatedly. This action incorporates air into the structure, creating the foundation for future holes. For cheeses like Swiss, where larger holes are desired, stretch the curd more vigorously and allow it to cool slightly between stretches. Conversely, for smaller holes, handle the curd more delicately and maintain a consistent temperature throughout.

A critical factor in hole formation is the role of *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, a bacterium that produces carbon dioxide gas during aging. This gas accumulates in the trapped air pockets, causing them to expand and form visible holes. To encourage this process, ensure the cheese is aged in a humid environment (85–90% humidity) at 18–24°C (64–75°F) for 3–6 months. Regularly monitor the cheese for mold or uneven aging, adjusting conditions as needed. The longer the aging period, the larger the holes will become, though this also depends on the initial air incorporation during stretching.

Comparing this process to other hole-forming methods in cheeses, such as the eyes in Cheddar or Gouda, highlights its uniqueness. While Cheddar’s holes result from trapped carbon dioxide during pressing, and Gouda’s from lactic acid bacteria activity, Swiss-style cheeses rely entirely on curd stretching and bacterial gas production. This distinction underscores the importance of mastering the stretching technique for achieving the desired hole characteristics. For home cheesemakers, practice and patience are key, as slight variations in stretching can significantly impact the final product.

In conclusion, the curd stretching process is a cornerstone of hole formation in cheeses like Swiss, blending precision with creativity. By controlling temperature, technique, and aging conditions, cheesemakers can manipulate hole size and distribution, crafting a product that is both visually striking and texturally unique. Whether you’re a professional or a hobbyist, understanding this process not only deepens your appreciation for cheese but also empowers you to experiment and innovate in your own creations.

The Sweet History: When Was Cheesecake First Invented?

You may want to see also

Aging conditions: Proper humidity and temperature during aging allow gas expansion, creating larger holes

The size and distribution of holes in cheese are not left to chance; they are the result of precise aging conditions. Humidity and temperature play a critical role in this process, acting as catalysts for gas expansion within the cheese matrix. During aging, bacteria produce carbon dioxide, which forms bubbles. If the environment is too dry or too cold, these bubbles remain small and trapped. However, at optimal humidity levels (typically 85-90%) and temperatures (around 10-13°C or 50-55°F), the gas expands, creating the larger, more uniform holes characteristic of cheeses like Emmental or Gruyère.

To achieve this, cheesemakers must carefully monitor aging conditions. For instance, maintaining humidity within the specified range prevents the cheese from drying out while allowing moisture to escape slowly, aiding gas expansion. Temperature control is equally vital; fluctuations can disrupt the bacterial activity responsible for gas production. A consistent temperature ensures that the bacteria work steadily, producing a steady stream of carbon dioxide. Practical tips include using humidity-controlled aging rooms and regularly flipping the cheese to ensure even exposure to the environment.

Comparing aging conditions across different cheeses highlights the importance of precision. For example, cheeses like Cheddar, which have minimal holes, are aged at lower humidity (around 80%) and cooler temperatures (7-10°C or 45-50°F), stifling gas expansion. In contrast, Swiss-type cheeses thrive in warmer, more humid conditions, fostering the development of their signature holes. This comparison underscores how slight adjustments in aging parameters can dramatically alter the final product.

Aging conditions are not just about hole formation; they also influence texture and flavor. Proper humidity and temperature allow enzymes to break down proteins and fats, contributing to the cheese’s complexity. However, cheesemakers must balance these factors to avoid over-expansion, which can lead to uneven holes or cracks. For home cheesemakers, investing in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment, such as a wine fridge with a hygrometer, can replicate professional aging conditions. Patience is key, as aging can take weeks to months, but the result—a cheese with perfectly formed holes—is well worth the effort.

The Surprising Science Behind Cheese's Irresistible Addiction Factor

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Type of milk used: Cow's milk proteins promote better gas retention, leading to more holes in certain cheeses

The type of milk used in cheesemaking plays a pivotal role in determining the presence and size of holes, scientifically known as "eyes." Cow's milk, in particular, contains proteins that excel at retaining gas produced during fermentation, making it a prime candidate for holey cheeses like Swiss or Emmental. This phenomenon is not merely a coincidence but a result of the unique composition of cow's milk, which includes higher levels of casein proteins compared to other milks. These proteins form a matrix that traps carbon dioxide bubbles, allowing them to expand and create the characteristic holes.

To understand this process, consider the steps involved in cheesemaking. During fermentation, lactic acid bacteria convert lactose into lactic acid, lowering the pH of the milk. Simultaneously, propionic acid bacteria produce carbon dioxide gas. In cow's milk, the casein proteins coagulate in a way that creates a semi-rigid structure, ideal for trapping these gas bubbles. The efficiency of this gas retention is directly linked to the milk’s protein content and structure, which is why cow's milk outperforms goat or sheep milk in producing holey cheeses. For instance, goat’s milk, with its smaller fat globules and different protein composition, tends to produce denser cheeses with fewer holes.

From a practical standpoint, cheesemakers can manipulate the hole-forming process by controlling factors such as milk temperature, acidity, and aging time. For example, maintaining a temperature of around 30°C (86°F) during fermentation encourages propionic acid bacteria activity, maximizing gas production. Additionally, using raw or thermized cow’s milk, which retains more native proteins, can enhance hole formation compared to pasteurized milk, where proteins may be denatured. Cheesemakers often monitor the curd’s texture and pH levels to ensure optimal conditions for gas retention, adjusting as needed to achieve the desired hole size and distribution.

A comparative analysis highlights the advantages of cow’s milk in holey cheese production. While sheep’s milk cheeses like Pecorino are prized for their richness, they rarely develop large holes due to their lower gas retention capacity. Similarly, buffalo milk, known for its high fat content, produces creamy cheeses like Mozzarella but lacks the protein structure needed for significant hole formation. Cow’s milk, with its balanced protein-to-fat ratio, strikes the perfect balance for creating airy, holey textures. This makes it the milk of choice for cheeses where eye development is a key characteristic.

In conclusion, the choice of cow’s milk in cheesemaking is not arbitrary but a deliberate decision rooted in science. Its protein composition fosters superior gas retention, enabling the formation of the large, evenly distributed holes that define cheeses like Emmental or Gruyère. By understanding this relationship, both cheesemakers and enthusiasts can appreciate the intricate interplay between milk type and cheese texture, turning a simple ingredient choice into a masterclass in culinary craftsmanship.

Discover the Cheese Notice App: Your Ultimate Guide to the Right One

You may want to see also

Cheese variety examples: Emmental and Gruyère are known for large holes due to specific production methods

The distinctive holes in Emmental and Gruyère cheeses, often referred to as "eyes," are not random occurrences but the result of a carefully orchestrated fermentation process. These holes, technically known as gas bubbles, are a hallmark of Swiss-type cheeses and are achieved through specific production methods that encourage the growth of particular bacteria. The key players in this process are *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* (or *P. freudenreichii*), which produce carbon dioxide gas as they metabolize lactic acid during the cheese's aging period. This gas becomes trapped within the curd, forming the characteristic holes.

To create these iconic cheeses, the process begins with the selection of specific starter cultures that include *P. freudenreichii*. After the milk is curdled and the whey is drained, the cheese is pressed into molds and then placed in a warm, humid environment to age. During the first few weeks, the cheese is turned and salted, creating an ideal habitat for the bacteria to thrive. The aging temperature is crucial; for Emmental, it is typically maintained between 20–24°C (68–75°F), while Gruyère ages at slightly cooler temperatures, around 18–20°C (64–68°F). This temperature range ensures the bacteria remain active, producing the gas that forms the holes.

The size and distribution of the holes in Emmental and Gruyère are influenced by the cheese's moisture content and the duration of aging. Emmental, aged for a minimum of 3 months, tends to have larger, more irregular holes due to its higher moisture content and longer aging period. Gruyère, aged for at least 5 months, has smaller, more evenly distributed holes, as its lower moisture content and denser texture restrict gas expansion. Both cheeses require precise control over humidity and temperature to achieve the desired eye formation, making their production a delicate balance of art and science.

For home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, replicating these cheeses requires attention to detail. Using a thermophilic starter culture containing *P. freudenreichii* is essential, as is maintaining consistent aging conditions. A DIY setup might include a temperature-controlled aging fridge or a cool, stable environment like a basement. Regularly monitoring the cheese's progress and adjusting humidity levels can help ensure the development of the signature holes. While the process is demanding, the reward is a cheese with a unique texture and flavor profile that elevates any dish, from fondue to grilled cheese sandwiches.

In comparison to other holey cheeses like Gouda or Cheddar, which may have smaller, irregular holes due to different bacteria or aging methods, Emmental and Gruyère stand out for their large, consistent eyes. This distinction highlights the precision required in their production and underscores why they are prized in culinary traditions worldwide. Whether enjoyed on a cheese board or melted into a dish, the holes in Emmental and Gruyère are a testament to the craftsmanship behind their creation, offering both visual appeal and a distinct mouthfeel that sets them apart from other cheeses.

Butter and Cheese: Are They Raising Your Triglyceride Levels?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The holes in cheese, also known as "eyes," are formed by carbon dioxide gas produced by bacteria during the aging process.

The bacteria *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* is primarily responsible for producing the carbon dioxide gas that creates the holes in cheeses like Swiss or Emmental.

No, only specific types of cheese, such as Swiss, Emmental, and some varieties of Gouda, naturally develop holes due to the bacterial activity in their production.

Yes, the size of the holes can be influenced by factors like the amount of bacteria present, the humidity and temperature during aging, and the curd handling process during cheese production.