Cheese, a beloved dairy product enjoyed worldwide, can have varying effects on the digestive tract system depending on its type and the individual consuming it. Rich in protein, fat, and calcium, cheese is generally well-tolerated by many, but its impact on digestion can differ significantly. For some, cheese aids in nutrient absorption and supports gut health due to its probiotic content in certain varieties like cheddar or gouda. However, for others, particularly those with lactose intolerance or dairy sensitivities, cheese can lead to discomfort, bloating, gas, or diarrhea, as the body struggles to break down lactose, a sugar found in dairy products. Additionally, the high fat content in some cheeses can slow digestion, potentially causing constipation in sensitive individuals. Understanding how cheese interacts with the digestive system is essential for optimizing dietary choices and maintaining gastrointestinal well-being.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Lactose Content | Many cheeses contain lactose, which can cause digestive issues in lactose-intolerant individuals, leading to bloating, gas, and diarrhea. Harder cheeses (e.g., cheddar, Swiss) have lower lactose levels. |

| Fat Content | High-fat cheeses can slow digestion, potentially causing discomfort or constipation in some individuals. |

| Protein Content | Cheese is rich in protein, which is generally well-tolerated but can be difficult to digest for those with conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). |

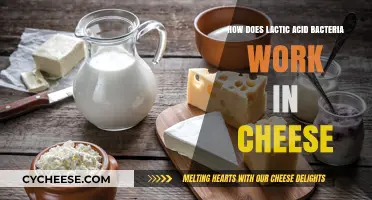

| Fermentation | Fermented cheeses (e.g., blue cheese, Gouda) contain probiotics that may support gut health by promoting beneficial gut bacteria. |

| Histamine Levels | Aged cheeses are high in histamine, which can trigger digestive symptoms like headaches, flushing, or gastrointestinal distress in histamine-intolerant individuals. |

| Saturated Fat Impact | Excessive saturated fat from cheese may alter gut microbiota, potentially increasing inflammation and negatively affecting gut health. |

| Calcium and Phosphorus | Cheese provides calcium and phosphorus, which are essential for gut health, but excessive intake may interfere with mineral absorption or cause constipation. |

| Allergenic Potential | Some individuals may have a milk protein allergy (e.g., casein), causing digestive symptoms like abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting. |

| Prebiotic Effects | Certain cheeses contain prebiotic fibers that can nourish beneficial gut bacteria, though this is less common compared to other dairy products. |

| Impact on Gut Motility | Cheese can slow gut motility due to its fat and protein content, potentially leading to constipation in sensitive individuals. |

| Individual Tolerance | Digestive responses to cheese vary widely based on factors like lactose tolerance, gut microbiome composition, and overall diet. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Lactose Intolerance Impact: Undigested lactose causes gas, bloating, diarrhea in intolerant individuals due to lactase deficiency

- Gut Microbiome Changes: Fermented cheeses introduce probiotics, promoting beneficial gut bacteria and improving digestion

- Fat Digestion Challenges: High-fat cheeses slow digestion, potentially causing discomfort or constipation in sensitive individuals

- Histamine Sensitivity: Aged cheeses contain histamine, triggering digestive issues like headaches or stomach pain in some

- Protein Breakdown: Cheese proteins are easily digestible, aiding nutrient absorption and reducing gastrointestinal strain

Lactose Intolerance Impact: Undigested lactose causes gas, bloating, diarrhea in intolerant individuals due to lactase deficiency

Undigested lactose in cheese wreaks havoc on the digestive systems of lactose-intolerant individuals, triggering a cascade of uncomfortable symptoms. This occurs due to a deficiency in lactase, the enzyme responsible for breaking down lactose, a sugar found in milk and dairy products. When lactase is lacking, lactose passes undigested into the large intestine, where it ferments, producing gas and drawing water into the gut. This fermentation process leads to the hallmark symptoms of lactose intolerance: gas, bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. The severity of these symptoms varies widely, depending on the degree of lactase deficiency and the amount of lactose consumed. For instance, someone with mild intolerance might tolerate small amounts of cheese, while others may experience severe reactions even with trace amounts.

Understanding the mechanism behind lactose intolerance is key to managing its impact. Lactase deficiency can be congenital, developing from birth, or acquired later in life due to factors like gastrointestinal infections or aging. In either case, the result is the same: the body’s inability to process lactose efficiently. Cheese, despite being lower in lactose than milk, still contains enough to trigger symptoms in sensitive individuals. Hard cheeses like cheddar or Swiss have lower lactose levels compared to soft cheeses like ricotta or cream cheese, making them potentially better options for those with mild intolerance. However, even trace amounts can cause discomfort for those with severe deficiency, underscoring the importance of individualized dietary adjustments.

Practical strategies can help lactose-intolerant individuals enjoy cheese with fewer adverse effects. Start by experimenting with small portions of low-lactose cheeses to gauge tolerance. Pairing cheese with other foods can slow digestion, reducing the concentration of lactose reaching the large intestine. Over-the-counter lactase enzymes, taken before consuming dairy, can also aid in lactose digestion, though effectiveness varies. For those with severe intolerance, dairy-free alternatives like almond or cashew cheese offer a viable solution. Keeping a food diary to track symptoms and triggers can provide valuable insights into personal tolerance levels, enabling better dietary choices.

Comparing lactose intolerance to other digestive conditions highlights its unique challenges. Unlike celiac disease, where gluten triggers an autoimmune response, lactose intolerance is a digestive enzyme deficiency, not an allergy or immune reaction. This distinction means that while symptoms can be severe, they are typically not life-threatening. However, the unpredictability of reactions and the social implications of avoiding dairy can significantly impact quality of life. Educating oneself and others about lactose intolerance fosters understanding and accommodation, whether at home or in social settings. With the right knowledge and tools, individuals can navigate their dietary restrictions while still enjoying a varied and satisfying diet.

In conclusion, the impact of undigested lactose on the digestive tract of intolerant individuals is both immediate and profound, driven by lactase deficiency. By understanding the science behind the symptoms and adopting practical strategies, those affected can mitigate discomfort and make informed choices. Whether through dietary modifications, enzyme supplements, or dairy alternatives, managing lactose intolerance empowers individuals to maintain digestive health without sacrificing culinary enjoyment. Awareness and adaptability are key to transforming a dietary limitation into an opportunity for healthier, more mindful eating.

How New Yorkers Order Their Iconic Bacon Egg and Cheese

You may want to see also

Gut Microbiome Changes: Fermented cheeses introduce probiotics, promoting beneficial gut bacteria and improving digestion

Fermented cheeses, such as cheddar, Gouda, and blue cheese, are not just culinary delights but also powerful allies for gut health. Unlike their fresh counterparts, these cheeses undergo a fermentation process that fosters the growth of probiotics—live microorganisms that confer health benefits when consumed in adequate amounts. These probiotics, primarily lactic acid bacteria, play a pivotal role in reshaping the gut microbiome, the complex ecosystem of bacteria residing in the digestive tract. By introducing these beneficial bacteria, fermented cheeses can help balance the gut flora, which is essential for optimal digestion and overall well-being.

To harness the gut-boosting benefits of fermented cheeses, consider incorporating them into your diet in moderation. A daily serving of 1–2 ounces (about 30–60 grams) can provide a sufficient dose of probiotics without overloading on calories or saturated fats. For example, pairing a slice of aged cheddar with an apple or adding crumbled blue cheese to a salad can be both delicious and functional. However, it’s crucial to choose high-quality, traditionally fermented cheeses, as mass-produced varieties may lack live cultures due to pasteurization or added preservatives. Reading labels for terms like "live cultures" or "naturally fermented" can guide your selection.

While fermented cheeses offer significant benefits, their impact on the gut microbiome varies depending on individual factors such as age, existing gut health, and dietary habits. For instance, older adults or those with compromised immune systems should consult a healthcare provider before increasing probiotic intake, as changes in gut bacteria can sometimes lead to temporary discomfort. Additionally, combining fermented cheeses with prebiotic-rich foods like garlic, onions, or bananas can amplify their effects, as prebiotics serve as food for probiotics, fostering their growth and activity in the gut.

A comparative analysis reveals that fermented cheeses stand out among probiotic sources due to their versatility and palatability. Unlike supplements, which can be costly or unappealing, cheese can be seamlessly integrated into meals, making it easier to maintain consistency. However, it’s important to note that cheese alone cannot replace a balanced diet rich in fiber, fruits, and vegetables, which are equally vital for gut health. Viewing fermented cheeses as a complementary tool rather than a standalone solution ensures a holistic approach to digestive wellness.

In conclusion, fermented cheeses offer a flavorful and practical way to support gut microbiome changes through their probiotic content. By understanding dosage, selecting quality products, and pairing them with prebiotic foods, individuals can maximize their digestive benefits. As with any dietary change, moderation and personalization are key, ensuring that the introduction of fermented cheeses aligns with broader health goals and individual needs.

Can Three Cheese Tortellini Ever Have Enough Cheese? Find Out!

You may want to see also

Fat Digestion Challenges: High-fat cheeses slow digestion, potentially causing discomfort or constipation in sensitive individuals

High-fat cheeses, such as cheddar, Parmesan, and blue cheese, can significantly slow digestion due to their dense lipid content. Fats require more time to break down compared to carbohydrates or proteins, as they must be emulsified by bile acids in the small intestine before absorption. This prolonged process can lead to a feeling of fullness or heaviness, particularly after consuming large portions. For individuals with sensitive digestive systems, this delay may exacerbate discomfort, making it essential to monitor portion sizes. A practical tip is to limit high-fat cheese intake to 1–2 ounces per serving, roughly the size of a pair of dice, to minimize digestive strain.

The impact of high-fat cheeses on digestion is particularly noticeable in individuals prone to constipation. Fats slow gastric emptying, the process by which food moves from the stomach to the small intestine, which can reduce bowel movement frequency. When combined with low fiber intake, a common dietary pattern in cheese-heavy meals, the risk of constipation increases. For example, pairing a high-fat cheese platter with crackers instead of fiber-rich vegetables or whole grains can worsen the issue. To counteract this, incorporate fiber sources like apples, carrots, or whole-grain bread when enjoying high-fat cheeses, ensuring a more balanced digestive response.

Sensitive individuals, including those with conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or lactose intolerance, may experience amplified discomfort from high-fat cheeses. The combination of fat content and potential lactose presence can trigger bloating, gas, or abdominal pain. For instance, aged cheeses like cheddar or Swiss contain less lactose but retain high fat levels, which may still pose challenges. A comparative approach suggests opting for lower-fat alternatives like mozzarella or feta, which digest more quickly and are less likely to cause issues. Always read labels to identify fat content, aiming for options with less than 5 grams of fat per serving for better tolerance.

To mitigate fat digestion challenges, consider timing and pairing strategies. Consuming high-fat cheeses earlier in the day allows more time for digestion, reducing the likelihood of nighttime discomfort. Additionally, pairing cheese with digestive enzymes or probiotics can aid in breaking down fats and maintaining gut health. For example, a supplement containing lipase, the enzyme responsible for fat digestion, may be beneficial for those with enzyme deficiencies. However, consult a healthcare provider before starting any supplement regimen, especially for older adults or individuals with pre-existing conditions, to ensure safety and efficacy.

Microwaving Chicken or Cheese Fries: Which Hungry Man Dish Wins?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Histamine Sensitivity: Aged cheeses contain histamine, triggering digestive issues like headaches or stomach pain in some

Aged cheeses, prized for their complex flavors and textures, harbor a compound that can turn indulgence into discomfort for some: histamine. This naturally occurring biogenic amine accumulates during the aging process, making varieties like cheddar, gouda, and blue cheese potential triggers for those with histamine sensitivity. Unlike a true allergy, this sensitivity stems from an impaired ability to break down histamine, leading to a buildup that mimics allergic reactions. Symptoms range from mild—think headaches or nasal congestion—to more severe gastrointestinal distress, including stomach pain, bloating, and diarrhea. Understanding this link is crucial for anyone navigating digestive issues without an obvious cause.

Consider the mechanism at play: histamine is metabolized primarily by the enzyme diamine oxidase (DAO). Individuals with low DAO activity, often due to genetic factors or conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), are more susceptible to histamine intolerance. A single serving of aged cheese, containing anywhere from 50 to 500 mg of histamine per 100 grams, can overwhelm their system. For context, symptoms often appear when daily histamine intake exceeds 100 mg, though thresholds vary. Tracking dietary histamine and monitoring portion sizes can help identify personal tolerance levels, allowing cheese lovers to enjoy their favorite varieties without repercussions.

Practical strategies exist for managing histamine sensitivity without eliminating cheese entirely. Opting for fresher, younger cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta, which contain minimal histamine, is a straightforward solution. Pairing aged cheeses with DAO-supporting foods, such as citrus fruits or parsley, may aid in histamine breakdown. Additionally, antihistamine medications, taken 30 minutes before consumption, can mitigate symptoms for occasional indulgence. However, these measures are not foolproof, and individuals with severe sensitivity may need to avoid aged cheeses altogether. Consulting a healthcare provider for DAO testing or an elimination diet can provide clarity and personalized guidance.

The interplay between histamine and the digestive tract highlights the complexity of food sensitivities. While aged cheeses are a culinary delight, their histamine content underscores the importance of listening to your body’s signals. For those affected, the goal isn’t deprivation but informed moderation. By understanding the science and adopting practical strategies, it’s possible to navigate histamine sensitivity without sacrificing the joy of cheese—just choose wisely, and savor mindfully.

Chipotle Quesadilla Cheese Mystery: Is It Really There?

You may want to see also

Protein Breakdown: Cheese proteins are easily digestible, aiding nutrient absorption and reducing gastrointestinal strain

Cheese, a staple in many diets worldwide, is not just a flavor enhancer but also a source of high-quality proteins that play a crucial role in digestive health. Unlike some proteins that can be hard on the stomach, cheese proteins are remarkably easy to digest. This is primarily due to the presence of whey and casein, two proteins that break down efficiently in the digestive tract. Whey protein, in particular, is known for its rapid absorption, making it an excellent choice for those looking to support muscle repair and overall health without overburdening their digestive system.

The ease of digestion of cheese proteins translates into better nutrient absorption. When proteins are broken down effectively, the body can more readily access essential amino acids, vitamins, and minerals present in cheese. For instance, calcium and phosphorus, vital for bone health, are absorbed more efficiently when consumed in the form of cheese. This is especially beneficial for individuals with sensitive stomachs or those recovering from gastrointestinal issues, as it minimizes the risk of discomfort while maximizing nutritional intake.

To optimize the digestive benefits of cheese proteins, consider incorporating moderate portions into your diet. A serving size of 30–40 grams (about 1–1.5 ounces) of cheese per day is generally sufficient to reap its nutritional advantages without overloading the digestive system. Pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole grains or vegetables can further enhance digestion by promoting a healthy gut environment. For older adults or those with lactose intolerance, opting for harder cheeses like cheddar or Swiss can be beneficial, as they contain lower lactose levels and are easier to digest.

While cheese proteins are gentle on the digestive tract, it’s essential to be mindful of individual tolerances. Some people may still experience mild discomfort due to lactose or other components in cheese. In such cases, starting with small amounts and gradually increasing intake can help the body adapt. Additionally, choosing high-quality, minimally processed cheeses can reduce the likelihood of digestive issues, as these products often retain more natural enzymes that aid in protein breakdown.

Incorporating cheese into a balanced diet can be a practical way to support digestive health while enjoying its rich flavor. For example, adding a slice of cheese to a morning omelet or using grated cheese as a topping for salads can provide a steady supply of easily digestible proteins throughout the day. By understanding how cheese proteins interact with the digestive system, individuals can make informed choices to enhance their overall well-being without compromising on taste or nutrition.

How Heating Cheese Alters Its Protein Structure: A Scientific Look

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, cheese can cause digestive issues, especially in individuals who are lactose intolerant or sensitive to dairy. Lactose, a sugar in milk, can lead to bloating, gas, diarrhea, and abdominal pain in those who lack the enzyme lactase to break it down.

Cheese contains probiotics, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which can promote a healthy gut microbiome by supporting beneficial bacteria. However, processed or aged cheeses may have fewer live cultures, reducing this benefit.

Cheese is high in fat, which can slow down the digestive process, leading to feelings of fullness and delayed stomach emptying. This can be beneficial for satiety but may cause discomfort in individuals with sensitive digestive systems.