Cheese becomes yellow primarily due to the presence of a natural pigment called annatto, which is derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. While some cheeses, like cheddar, naturally develop a pale yellow hue from the carotene in grass-fed cows' milk, many commercially produced cheeses are artificially colored with annatto to achieve a more vibrant, consistent yellow appearance. This practice dates back centuries and is widely used today to meet consumer expectations, as brighter yellow cheese is often associated with higher quality and richer flavor. However, it’s important to note that the color of cheese does not necessarily indicate its taste or nutritional value, as both yellow and white cheeses can be equally delicious and nutritious.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Source of Yellow Color | Primarily from annatto, a natural dye derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. |

| Role of Annatto | Added during the cheesemaking process to impart a consistent yellow hue. |

| Natural Pigments | Carotene (from cow's milk diet) contributes to a pale yellow color. |

| Diet of Dairy Cows | Cows fed fresh grass produce milk with higher carotene levels, affecting cheese color. |

| Processed Cheese | Artificial colorings (e.g., beta-carotene) are often used for uniformity. |

| Traditional Cheese | Relies on annatto or natural milk pigments for color. |

| Historical Use of Annatto | Used since the 16th century to standardize cheese appearance. |

| Consumer Preference | Yellow cheese is often associated with higher quality or maturity. |

| Regional Variations | European cheeses may use less annatto, relying more on natural milk color. |

| Health Implications | Annatto is generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the FDA. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Role of Annatto: Natural dye from achiote trees, commonly added to impart yellow-orange hue

- Carotene Content: Milk from grass-fed cows contains beta-carotene, naturally coloring cheese yellow

- Aging Process: Longer aging intensifies yellow color due to protein breakdown and carotene concentration

- Artificial Colorants: Synthetic dyes like beta-carotene are sometimes used for consistent yellow appearance

- Milk Source: Goat or sheep milk cheeses are often whiter, while cow’s milk tends toward yellow

Role of Annatto: Natural dye from achiote trees, commonly added to impart yellow-orange hue

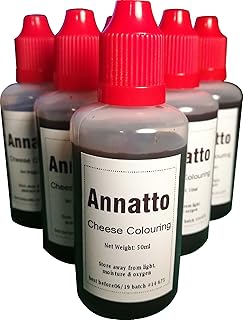

The vibrant yellow-orange hue of many cheeses isn’t always a product of natural aging or milk composition. Enter annatto, a natural dye derived from the seeds of the achiote tree, scientifically known as *Bixa orellana*. This plant-based colorant has been used for centuries in food and textiles, but its role in cheesemaking is particularly intriguing. Annatto is added to cheeses like Cheddar, Colby, and Red Leicester to achieve a consistent, appealing color that consumers associate with quality and maturity. Unlike synthetic dyes, annatto is prized for its natural origin, making it a preferred choice in artisanal and mass-produced cheeses alike.

To incorporate annatto into cheese, manufacturers typically use it in powdered or liquid form, often diluted in oil or water for even distribution. The dosage varies depending on the desired shade and type of cheese, but a common range is 0.01% to 0.05% of the total cheese weight. For example, in a 10-kilogram batch of Cheddar, 1 to 5 grams of annatto extract might be added. It’s crucial to mix the dye thoroughly during the curd-making process to avoid streaking or uneven coloration. While annatto doesn’t alter the flavor significantly, some cheesemakers note a subtle earthy or nutty undertone, which can complement certain cheese varieties.

One of the key advantages of annatto is its stability. Unlike carotene, a naturally occurring pigment in milk that fades over time, annatto retains its color throughout the aging process. This makes it ideal for cheeses intended for long-term storage or export, ensuring they maintain their visual appeal. However, it’s essential to source high-quality annatto extract, as inferior products may contain impurities or fail to disperse properly. Cheesemakers should also be mindful of consumer preferences, as some markets prioritize natural ingredients and may scrutinize the use of additives, even natural ones.

For home cheesemakers, experimenting with annatto can be a rewarding way to customize cheese color. Start with a small batch and use pre-diluted annatto oil for ease of application. Add the dye gradually, stirring continuously, and observe how the color develops as the curds form. Keep in mind that annatto’s hue can vary depending on its concentration and the pH of the cheese, so trial and error is often necessary. While it’s not essential for flavor, annatto can elevate the visual appeal of homemade cheeses, making them more marketable or simply more enjoyable to serve.

In the broader context of food transparency, annatto’s role in cheese coloration highlights the intersection of tradition and innovation. As consumers increasingly demand natural ingredients, annatto offers a solution that aligns with clean-label trends. However, it’s important to educate buyers about its purpose, as some may mistakenly associate color with artificial additives. By embracing annatto responsibly, cheesemakers can strike a balance between meeting market expectations and preserving the integrity of their craft. Whether in a factory or a farmhouse, this ancient dye continues to play a modern, practical role in shaping the cheese we love.

Why Cheese is Yellow: Unraveling the Mystery of White Milk

You may want to see also

Carotene Content: Milk from grass-fed cows contains beta-carotene, naturally coloring cheese yellow

The vibrant yellow hue of cheese often begins in lush green pastures. Grass-fed cows consume fresh forage rich in beta-carotene, a pigmented antioxidant. Their bodies absorb this compound, which then dissolves into the milk fat, imparting a golden tint. This natural process explains why cheeses made from grass-fed milk often exhibit a deeper, richer color compared to those from grain-fed cows.

To maximize beta-carotene content in cheese, farmers can strategically manage grazing. Rotational grazing ensures cows access the most nutrient-dense grass, typically during peak growth phases. Studies suggest milk from cows grazing on diverse pastures can contain up to 50% more beta-carotene than milk from confined, grain-fed animals. For cheesemakers, this translates to a more pronounced yellow color without artificial additives.

Not all cheeses benefit equally from beta-carotene. Hard cheeses like cheddar or Gouda retain more of the pigment due to their lower moisture content, allowing the color to concentrate. Softer cheeses, such as Brie or Camembert, may show a subtler hue because the pigment disperses in their higher water content. Understanding this relationship helps producers tailor their methods to achieve the desired color intensity.

For consumers, choosing cheese from grass-fed milk offers more than aesthetic appeal. Beta-carotene is a precursor to vitamin A, essential for immune function and vision. While the amount in cheese is modest, it contributes to a diet rich in natural nutrients. Look for labels indicating "grass-fed" or "pasture-raised" to ensure you’re selecting cheese with this added benefit.

Incorporating beta-carotene-rich cheese into your diet is simple. Pair sharp, yellow cheddar with apples for a snack that combines flavor and nutrition. Use aged Gouda in grilled cheese sandwiches to highlight its deep color and nutty taste. By embracing cheese from grass-fed cows, you support sustainable farming practices while enjoying a naturally vibrant product.

Perfectly Shredded Beef: Mastering the Philly Cheesesteak Technique

You may want to see also

Aging Process: Longer aging intensifies yellow color due to protein breakdown and carotene concentration

The longer cheese ages, the deeper its yellow hue becomes. This transformation isn’t merely aesthetic; it’s a biochemical process rooted in protein breakdown and carotene concentration. As cheese matures, proteolytic enzymes gradually dismantle complex proteins into simpler compounds, including amino acids and peptides. This breakdown releases molecules that interact with naturally occurring carotenoids, pigments responsible for yellow and orange tones in milk. Over time, these interactions intensify the color, creating the rich, golden shades prized in aged cheeses like Cheddar or Gruyère.

To understand this process, consider the role of carotene in milk. Carotene, derived from the cows’ forage, is fat-soluble and dispersed throughout the milkfat. During aging, as moisture evaporates and the cheese matrix tightens, the concentration of carotene increases relative to the cheese’s volume. Simultaneously, the breakdown of proteins reduces light scattering, allowing the carotene’s color to shine through more vividly. For example, a young Cheddar aged 3 months may have a pale yellow tint, while a 24-month vintage could display a deep, amber hue.

Practical tip: If you’re aging cheese at home, monitor humidity (ideally 85–90%) and temperature (50–55°F) to ensure optimal protein breakdown and carotene concentration. Avoid excessive heat, as it can accelerate aging unevenly, leading to off-flavors or texture issues. For best results, use raw or pasteurized milk with higher carotene content, such as from grass-fed cows, to enhance the final color.

Comparatively, cheeses aged for shorter periods, like fresh mozzarella or young Gouda, retain a lighter color due to minimal protein breakdown and lower carotene concentration. In contrast, long-aged cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano or aged Gouda showcase the full spectrum of this process, with their deep yellow or even orange-brown tones serving as a visual marker of maturity. This color evolution isn’t just a sign of age—it’s a testament to the intricate chemistry happening within the cheese.

Takeaway: The yellowing of cheese through aging is a natural, science-driven process that rewards patience. By understanding the interplay of protein breakdown and carotene concentration, you can better appreciate—and even control—the color development in your favorite cheeses. Whether you’re a home cheesemaker or a connoisseur, this knowledge deepens your connection to the craft and the final product.

Converting Cheese Measurements: How Many Pounds is 8 Ounces?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Artificial Colorants: Synthetic dyes like beta-carotene are sometimes used for consistent yellow appearance

Cheese's yellow hue often relies on a subtle yet impactful addition: artificial colorants. While natural factors like cow feed contribute to color, synthetic dyes like beta-carotene offer consistency, ensuring every block of cheddar or slice of American cheese meets consumer expectations. This practice, though sometimes controversial, addresses the variability inherent in natural cheese production.

Understanding Beta-Carotene's Role

Beta-carotene, a pigment found in carrots and other orange-hued foods, is a common choice for cheese coloring. Its safety and stability make it a preferred option for manufacturers. When added to cheese, beta-carotene imparts a warm, yellow tone that remains consistent across batches. The dosage is crucial: typically, 0.05% to 0.1% of beta-carotene by weight is sufficient to achieve the desired shade without overwhelming the cheese's natural flavor.

The Process of Incorporation

Incorporating beta-carotene into cheese involves precision. The dye is often dissolved in a fat-soluble medium, such as oil or butter, before being mixed into the cheese curds during the manufacturing process. This ensures even distribution and prevents clumping. For home cheesemakers, beta-carotene powder can be added to milk before coagulation, though achieving uniformity requires careful stirring. Always follow recommended dosages, as excessive amounts can lead to an unnatural, overly vibrant color.

Comparing Natural vs. Synthetic Coloring

While natural colorants like annatto seeds have been used for centuries, synthetic dyes like beta-carotene offer distinct advantages. Natural colorants can vary in intensity depending on the source, leading to inconsistencies. Synthetic dyes, on the other hand, provide a reliable and reproducible result. However, consumers increasingly seek transparency in food production, prompting some manufacturers to label products with synthetic colorants clearly. This shift highlights the importance of balancing consistency with consumer preferences.

Practical Tips for Cheese Enthusiasts

For those curious about cheese coloring, understanding labels is key. Look for terms like "beta-carotene" or "color added" on packaging. If you're making cheese at home, experiment with small batches to find the right balance of colorant. Remember, the goal is to enhance, not overpower, the cheese's natural qualities. For children, who are often drawn to vibrant colors, cheeses with synthetic dyes can be a fun way to encourage dairy consumption, though always prioritize moderation and a balanced diet.

The Takeaway

Artificial colorants like beta-carotene play a significant role in the cheese industry, offering consistency in a product where natural variation is the norm. While the debate between natural and synthetic continues, understanding the process and purpose behind these additives empowers consumers to make informed choices. Whether you're a manufacturer, home cheesemaker, or simply a cheese lover, recognizing the science behind the yellow hue adds a new layer of appreciation to this beloved food.

What is Easy Cheese? A Quick Guide to the Classic Snack

You may want to see also

Milk Source: Goat or sheep milk cheeses are often whiter, while cow’s milk tends toward yellow

The color of cheese is a subtle yet significant indicator of its origin and composition, with milk source playing a pivotal role. Goat and sheep milk cheeses, such as fresh chèvre or manchego, often retain a whiter hue due to lower levels of carotene, a natural pigment found in the milk. In contrast, cow’s milk cheeses, like cheddar or Gouda, tend toward a more pronounced yellow color because cows consume grass and hay rich in beta-carotene, which is transferred into their milk. This natural variation in carotene content is the primary reason why cheeses from different milk sources exhibit distinct color profiles.

To understand this phenomenon, consider the diet of the animals. Grazing cows ingest large amounts of green forage, which is high in beta-carotene, a precursor to vitamin A. Their bodies break down beta-carotene, releasing carotene into their milk, which imparts a yellow tint. Goats and sheep, on the other hand, often browse on shrubs, leaves, and other vegetation that contain less beta-carotene, resulting in milk with lower pigment levels. For cheese makers, this means the milk’s natural color directly influences the final product, with minimal need for artificial additives in traditional practices.

For those looking to experiment with cheese making, the milk source is a critical factor in achieving the desired color. If you aim for a whiter cheese, opt for goat or sheep milk, which requires little to no adjustment. For a yellower cheese, cow’s milk is ideal, though you can enhance the color further by using milk from grass-fed cows during peak grazing seasons, such as spring and summer. Alternatively, some producers add annatto, a natural dye derived from the achiote tree, to intensify the yellow hue, but this is more common in mass-produced cheeses than artisanal varieties.

A comparative analysis reveals that the whiteness of goat and sheep milk cheeses is not just aesthetic but also tied to flavor and texture. These cheeses often have a tangier, more acidic profile and a crumbly or creamy consistency, which pairs well with their lighter color. Cow’s milk cheeses, with their richer carotene content, tend to have a milder, buttery flavor and a firmer texture, complementing their deeper yellow tone. This interplay between color, taste, and mouthfeel highlights how milk source shapes the overall character of the cheese.

In practical terms, consumers can use color as a clue to the cheese’s origin and potential flavor. A bright white goat cheese like chèvre suggests a sharp, fresh taste, ideal for salads or spreads. A deep yellow cheddar indicates a creamy, nutty profile, perfect for melting or snacking. By understanding the role of milk source in cheese color, enthusiasts can make more informed choices, whether selecting a cheese for a specific dish or simply appreciating the craftsmanship behind each wheel.

Do Cheese Mites Experience Pain? Exploring the Ethics of Dairy Production

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese becomes yellow primarily due to the presence of a natural pigment called carotene, which is found in the grass and plants that cows eat. This pigment is absorbed into the cow's milk and then transferred to the cheese during production.

No, not all cheese naturally turns yellow. The color of cheese depends on the diet of the animal producing the milk and whether artificial colorings are added. Cheese from cows fed on fresh grass tends to be yellower, while cheese from grain-fed cows or goats may be whiter.

Yes, cheese can be made yellow artificially by adding annatto, a natural food coloring derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. This practice is common in mass-produced cheeses to achieve a consistent yellow hue.

Some cheese is white because the milk used to make it contains less carotene, often due to the animal's diet or the type of animal (e.g., goats or sheep). Additionally, some cheeses are intentionally kept white to maintain a specific appearance or tradition.

The yellow color of cheese, whether natural or artificial, does not significantly affect its taste. The flavor of cheese is determined by factors like the type of milk, aging process, bacteria, and production methods, not by its color.