Cheese becomes yellow primarily due to the presence of a natural pigment called annatto, which is derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. While some cheeses, like cheddar, naturally develop a pale yellow hue from the carotene in the milk of grass-fed cows, many commercially produced cheeses are artificially colored with annatto to achieve a more vibrant, consistent yellow appearance. This practice dates back centuries and is widely used today to enhance the visual appeal of cheeses, as consumers often associate deeper yellow shades with higher quality or richer flavor. However, the yellow color itself does not significantly impact the taste or nutritional value of the cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Source of Yellow Color | Primarily from carotene (carotenoids), naturally occurring pigments found in the grass and plants cows eat. |

| Role of Cow's Diet | Cows that graze on fresh, green grass produce milk with higher levels of carotene, leading to yellower cheese. |

| Processing and Aging | Carotene is fat-soluble, so it accumulates in the milkfat. During cheese making, the fat content and aging process can intensify the yellow color. |

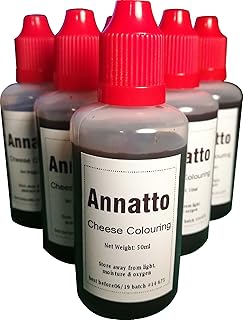

| Artificial Colorants | Some cheeses may have annatto, a natural orange-yellow dye derived from the achiote tree, added to enhance color. |

| Type of Cheese | Harder, aged cheeses tend to be yellower due to higher fat content and longer aging, allowing more carotene concentration. |

| Seasonal Variation | Cheese made from milk produced in spring and summer, when cows graze on fresh grass, is typically yellower than cheese made in winter. |

| Breed of Cow | Certain breeds, like Jersey cows, naturally produce milk with higher butterfat content, which can contribute to a deeper yellow color. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Role of Annatto: Natural dye from achiote trees, commonly added to impart yellow-orange hue

- Carotene in Milk: Cows' diet rich in green grass produces milk with beta-carotene, turning cheese yellow

- Aging Process: Longer aging intensifies yellow color due to protein breakdown and carotene concentration

- Cheese Varieties: Cheddar, Colby, and Mimolette are naturally or artificially colored yellow

- Artificial Colorants: Synthetic dyes like beta-carotene or annatto substitutes are sometimes used for consistency

Role of Annatto: Natural dye from achiote trees, commonly added to impart yellow-orange hue

Cheese's yellow hue often comes from annatto, a natural dye derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. This vibrant colorant, extracted from the seed’s outer coating, has been used for centuries in food and textiles. In cheese production, annatto is added during the curdling process, infusing the milk with a yellow-orange tint that mimics the natural color of grass-fed cows’ milk. Its use is particularly common in cheeses like Cheddar, Colby, and Mimolette, where a consistent, appealing appearance is desired. Unlike artificial dyes, annatto is plant-based, making it a preferred choice for producers aiming for a more natural product.

The application of annatto in cheese-making is both an art and a science. Typically, the dye is dissolved in a small amount of water or oil before being mixed into the milk. Dosage is critical: 0.1 to 0.5 grams of annatto extract per kilogram of milk is sufficient to achieve the desired shade. Overuse can result in an unnaturally bright or uneven color, while too little may leave the cheese pale. For home cheesemakers, annatto can be purchased as a powder, paste, or liquid, with liquid forms being the easiest to incorporate evenly. Always add the dye gradually, stirring thoroughly to ensure uniform distribution.

One of the key advantages of annatto is its stability. Unlike some natural colorants, it withstands the heat and acidity of the cheese-making process without fading. This makes it ideal for both fresh and aged cheeses. However, its use isn’t without controversy. While annatto is generally recognized as safe, some individuals report mild allergic reactions, such as skin rashes or digestive discomfort. Producers should clearly label annatto-containing cheeses to inform consumers, especially those with sensitivities.

Comparatively, annatto stands out among other cheese colorants. Beta-carotene, derived from carrots or algae, produces a more orange hue and is often used in organic cheeses. Synthetic dyes like Yellow 5 or 6 are cheaper but lack the natural appeal of annatto. For artisanal cheesemakers, annatto strikes a balance between tradition and modernity, offering a reliable, plant-based solution. Its historical use in cultures from Latin America to Europe further cements its role as a time-tested ingredient.

In practice, incorporating annatto into cheese production requires attention to detail. For best results, add the dye during the initial stages of curdling, ensuring it blends seamlessly with the milk proteins. Home cheesemakers can experiment with different dosages to achieve varying shades, from pale yellow to deep orange. Always source annatto from reputable suppliers to ensure purity and potency. By mastering its use, producers can enhance the visual appeal of their cheeses while maintaining a natural, authentic character. Annatto isn’t just a dye—it’s a tool for crafting cheese that delights both the eyes and the palate.

Is Domino's Cheese in the USA Made with Animal Rennet?

You may want to see also

Carotene in Milk: Cows' diet rich in green grass produces milk with beta-carotene, turning cheese yellow

The vibrant yellow hue of cheese is often a result of a natural pigment called beta-carotene, which originates from the diet of dairy cows. When cows graze on lush, green pastures, they consume an abundance of beta-carotene, a precursor to vitamin A, found in the chlorophyll-rich grass. This fat-soluble compound is then absorbed into the cow's bloodstream and eventually makes its way into their milk. The presence of beta-carotene in milk is a direct consequence of the cow's diet, offering a fascinating insight into the connection between agriculture and dairy products.

The Science Behind the Color: Beta-carotene belongs to a class of pigments known as carotenoids, which are responsible for the yellow, orange, and red colors in various fruits and vegetables. In the case of cheese, the beta-carotene in milk is converted into a yellow pigment during the cheese-making process. This transformation occurs due to the action of bacteria and enzymes, which break down the beta-carotene molecules, releasing the vibrant yellow color. The intensity of the yellow hue can vary depending on the concentration of beta-carotene in the milk, which is directly influenced by the cow's diet.

For farmers and cheesemakers, understanding this relationship is crucial. To produce cheese with a rich, natural yellow color, cows should be grazed on fresh, green pastures during the growing season. Research suggests that the beta-carotene content in milk can increase significantly when cows consume grass with a high leaf-to-stem ratio, typically found in well-managed pastures. For instance, a study published in the *Journal of Dairy Science* found that milk from pasture-fed cows contained up to 50% more beta-carotene compared to cows fed on conserved forage. This highlights the importance of pasture management in achieving the desired cheese color.

Practical Considerations: To maximize beta-carotene levels in milk, farmers can implement specific grazing strategies. Rotational grazing, where cows are moved to fresh pastures regularly, ensures access to the most nutrient-dense grass. Additionally, supplementing the cows' diet with carotene-rich feeds, such as certain types of hay or silage, can further enhance milk carotene levels during periods when fresh grass is scarce. It's worth noting that the conversion of beta-carotene to vitamin A in the human body is also beneficial, providing consumers with an additional nutritional advantage.

In the context of cheese production, the natural yellow color derived from beta-carotene is highly desirable, as it indicates a traditional, pasture-based farming system. This is particularly valued in the production of artisanal and specialty cheeses, where consumers appreciate the connection to natural, sustainable practices. By focusing on the cow's diet and pasture management, farmers and cheesemakers can create a product that not only tastes exceptional but also tells a story of quality and authenticity through its vibrant yellow appearance.

Quarter Pounder with Cheese: Unveiling the Iconic Burger's Menu Number

You may want to see also

Aging Process: Longer aging intensifies yellow color due to protein breakdown and carotene concentration

The longer cheese ages, the deeper its yellow hue becomes. This transformation isn’t accidental—it’s a result of two key processes: protein breakdown and carotene concentration. As cheese matures, proteins degrade into amino acids, some of which react with naturally occurring sugars to form compounds that enhance yellow pigmentation. Simultaneously, the concentration of carotene, a pigment found in milk fat, intensifies as moisture evaporates, leaving behind a richer color. This dual mechanism explains why aged cheeses like cheddar or Gruyère develop their signature golden tones.

To understand this better, consider the role of carotene in milk. Cows that graze on fresh grass produce milk with higher levels of carotene, which is why cheeses made from grass-fed milk often start with a more vibrant yellow base. During aging, as moisture is lost through evaporation, the carotene becomes more concentrated, amplifying the color. For example, a young cheddar aged 6 months may have a pale yellow hue, while a 24-month vintage cheddar will display a deep, almost orange-yellow shade. This progression is both predictable and controllable, making it a valuable tool for cheesemakers aiming for specific color profiles.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers or enthusiasts include monitoring humidity and temperature during aging, as these factors influence moisture loss and, consequently, carotene concentration. Aim for a consistent environment—ideally, 50–55°F (10–13°C) with 85–90% humidity—to ensure even aging. For those seeking a pronounced yellow color, start with milk from grass-fed cows and extend the aging period beyond 12 months. However, be cautious: overly long aging can lead to brittleness or off-flavors, so regular tasting is essential.

Comparatively, cheeses aged for shorter periods, like fresh mozzarella or young gouda, retain a pale ivory or light yellow color because their aging process is truncated, limiting protein breakdown and carotene concentration. In contrast, hard cheeses like Parmesan or aged Gouda undergo years of maturation, resulting in a dense, crumbly texture and a deep, rich yellow color. This comparison highlights how aging duration directly correlates with color intensity, offering a clear roadmap for achieving desired hues.

In conclusion, the aging process is a deliberate, science-backed method for intensifying cheese’s yellow color. By understanding the interplay of protein breakdown and carotene concentration, cheesemakers can manipulate aging conditions to achieve specific visual and textural outcomes. Whether crafting a mild, pale cheese or a bold, golden masterpiece, mastering this process unlocks a world of creative possibilities.

Cheese and Water Retention: Fact or Fiction? Uncover the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cheese Varieties: Cheddar, Colby, and Mimolette are naturally or artificially colored yellow

The vibrant yellow hue of certain cheeses is not merely a coincidence but a result of specific processes, both natural and artificial. Among the myriad of cheese varieties, Cheddar, Colby, and Mimolette stand out for their distinctive yellow shades, which are achieved through different methods. Understanding these processes not only satisfies curiosity but also empowers cheese enthusiasts to make informed choices.

Natural Coloring in Cheese: A Gift from Bovine Diet

The yellow color in cheeses like Cheddar and Colby often originates from the diet of the cows that produce the milk. When cows graze on fresh pasture rich in beta-carotene, a pigment found in green plants, their milk absorbs this compound. During the cheese-making process, beta-carotene is concentrated in the fat content of the milk, resulting in a natural yellow hue. For instance, grass-fed cows in regions with lush pastures yield milk that produces deeper yellow cheeses. To enhance this effect, some farmers supplement their cows’ diets with carotene-rich feeds, ensuring consistent coloration. This method is not only natural but also aligns with traditional cheese-making practices.

Artificial Coloring: Precision in Pigmentation

Not all yellow cheeses rely on nature’s palette. Mimolette, a French cheese known for its bright orange rind, often achieves its color through the addition of annatto, a natural dye derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. Annatto is widely used in the cheese industry for its ability to produce uniform yellow to orange shades. In the U.S., Colby cheese sometimes incorporates annatto to ensure a consistent appearance, especially when cows’ diets vary seasonally. The FDA regulates the use of annatto, ensuring it is safe for consumption. Typically, annatto is added in concentrations of 50–200 parts per million (ppm) during the curdling process, depending on the desired intensity of color.

Comparing Methods: Natural vs. Artificial

While both natural and artificial coloring methods achieve yellow cheese, they differ in origin and perception. Natural coloring, dependent on bovine diet, varies with seasons and farming practices, making it less predictable but more appealing to purists. Artificial coloring, on the other hand, offers consistency and control, ensuring every batch of cheese meets consumer expectations. Mimolette’s use of annatto exemplifies this approach, as its vibrant color is a hallmark of the cheese’s identity. However, some consumers prefer the subtlety of naturally colored cheeses, associating it with higher quality and traditional craftsmanship.

Practical Tips for Cheese Lovers

For those seeking naturally yellow cheeses, look for labels indicating grass-fed or pasture-raised cows. These cheeses may vary in shade but offer a connection to seasonal and sustainable farming practices. If consistency is key, opt for cheeses like Mimolette or Colby, which often use annatto for uniform coloring. When experimenting with cheese recipes, consider that artificially colored cheeses may yield more vibrant dishes, while naturally colored varieties add a rustic charm. Regardless of preference, understanding the source of the yellow hue enhances appreciation for the art and science of cheese-making.

Ultimate Meat and Cheese Burrito: Ingredients, Flavors, and Perfect Assembly

You may want to see also

Artificial Colorants: Synthetic dyes like beta-carotene or annatto substitutes are sometimes used for consistency

Cheese's yellow hue often relies on artificial colorants, a practice that sparks both curiosity and concern. While natural pigments like annatto and beta-carotene are commonly used, their synthetic counterparts offer a different set of advantages and challenges. These artificial dyes, chemically engineered to mimic natural colors, provide manufacturers with a level of consistency that natural sources cannot always guarantee. For instance, annatto, derived from the seeds of the achiote tree, can vary in intensity depending on the crop and processing methods. Synthetic alternatives, however, deliver a uniform shade batch after batch, ensuring that every block of cheddar or slice of American cheese meets consumer expectations.

The use of synthetic dyes like beta-carotene substitutes or annatto mimics is not merely about aesthetics; it’s a strategic decision rooted in practicality. Natural colorants are susceptible to degradation from light, heat, and pH changes, which can alter the cheese’s appearance over time. Synthetic dyes, on the other hand, are designed to be more stable, maintaining their vibrancy throughout the product’s shelf life. This stability is particularly crucial in mass-produced cheeses, where consistency is key to brand recognition and consumer trust. For example, a study published in the *Journal of Dairy Science* found that synthetic beta-carotene retained 90% of its color intensity after six months of storage, compared to 70% for its natural counterpart.

However, the adoption of artificial colorants is not without controversy. Health-conscious consumers often scrutinize synthetic additives, questioning their safety and long-term effects. Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EFSA have established strict guidelines for their use, ensuring they are safe for consumption in approved quantities. For instance, the acceptable daily intake (ADI) for synthetic beta-carotene is set at 0–0.27 mg/kg of body weight, a level deemed safe for all age groups. Despite this, some prefer to avoid synthetic dyes altogether, opting for cheeses colored exclusively with natural ingredients. This preference has spurred innovation, with manufacturers exploring plant-based alternatives like turmeric or paprika extracts to achieve similar results.

For those interested in navigating the world of artificially colored cheeses, understanding labels is essential. Look for terms like "artificial color added" or specific dye names such as "beta-carotene (synthetic)" in the ingredient list. If you’re aiming to avoid synthetic dyes, seek out products labeled "colored with annatto" or "naturally colored." Additionally, consider the context of consumption: while synthetic dyes may be more stable in processed cheese slices used for grilling, natural colorants might suffice for artisanal cheeses enjoyed fresh. By making informed choices, consumers can balance their desire for consistency with their commitment to health and natural ingredients.

In conclusion, artificial colorants play a significant role in achieving the consistent yellow hue of many cheeses, offering stability and uniformity that natural pigments often lack. While they are rigorously tested for safety, their use remains a point of contention among consumers. By understanding the science behind these dyes and reading labels carefully, cheese lovers can make choices that align with their values and preferences, whether they prioritize consistency, health, or natural ingredients.

What is the Cheese Grater Foot Tool and How Does it Work?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese becomes yellow primarily due to the presence of a natural pigment called carotene, which is found in the grass and plants that cows eat. When cows consume these plants, the carotene is absorbed into their milk fat, giving the milk a yellowish tint. During the cheese-making process, this carotene is concentrated, resulting in yellow cheese.

Not necessarily. While many yellow cheeses get their color from natural carotene in milk, some cheeses are artificially colored using annatto, a natural dye derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. This practice is common in cheeses like Cheddar to achieve a consistent yellow hue, regardless of the cows' diet.

Yes, some cheeses may appear yellow due to other factors, such as aging or the type of milk used. For example, aged cheeses can develop a yellowish rind due to bacterial activity, and cheeses made from goat or sheep milk may have a natural yellowish tint due to differences in milk composition. However, these are less common sources of yellow color compared to carotene or annatto.