Cheese is a beloved food product with hundreds of varieties produced worldwide, each with distinct styles, textures, and flavours. Despite being made from the same base ingredient, milk, the diverse range of cheese types and flavours is a result of different production methods and processes. The flavour of cheese is influenced by various factors, including the origin of the milk, pasteurization, butterfat content, bacteria and mould, processing techniques, and ageing. The unique culture and environment of different regions also play a role in the distinct flavours of cheese. The complex biochemistry of flavour generation in cheese involves microbiological, enzymatic, and chemical changes during ripening, contributing to the individual character of each variety.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Milk | Flavour varies depending on what the animals are fed, their breed, and whether it is pasteurised or unpasteurised |

| Bacteria | Different bacteria create distinct flavours |

| Mould | Surface mould creates a runny texture and develops flavour |

| Alcohol | Alcohol brushed onto cheese can remain and impact flavour |

| Production Method | Different production methods can create unique flavours |

| Ageing | Length of ageing impacts flavour |

| Region | Regional differences in feed, climate, and production techniques influence flavour |

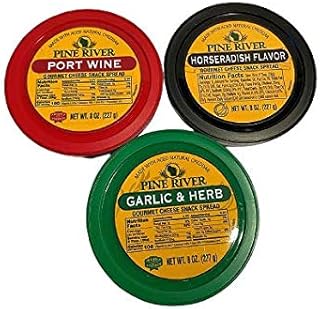

Explore related products

Pasteurisation

HTST pasteurisation, also known as flash pasteurisation, is the most common method for heating milk quickly to a high temperature. Milk is heated to 72°C for 15 seconds, although some sources state 71.7°C (161°F). This method effectively kills harmful bacteria such as Salmonella, Listeria, and E. coli, but it also destroys beneficial bacteria and enzymes that contribute to the flavour and texture of cheese. As a result, cheese made with pasteurised milk often has a milder taste and a more uniform texture.

LTLT pasteurisation, on the other hand, involves heating milk to 63°C for 30 minutes and then cooling it. This method is less damaging to the milk's natural bacteria, resulting in better cheesemaking results. However, it requires more time and energy than HTST. Most small-scale and artisanal cheesemakers prefer LTLT pasteurisation due to its gentler effect on milk.

Another option is thermalisation, a heating step used by some cheesemakers as a compromise between pasteurised and raw milk. Milk is heated to a lower temperature than in HTST or LTLT, and it is still legally considered raw. However, cheese made with thermised milk must be aged for at least 60 days to allow time for the built-in safeguards, such as acid development and salt content, to combat potential pathogen growth.

The use of pasteurisation in cheesemaking has its benefits and drawbacks. It improves food safety by reducing the risk of foodborne illnesses caused by harmful bacteria. Pasteurised cheese is perceived as safer and is widely available, dominating the market in many countries. However, pasteurisation can also kill beneficial bacteria and enzymes that contribute to the flavour and texture of cheese, making it challenging to produce cheese with the same complex flavour and texture as raw milk cheese.

Some cheesemakers who prioritise flavour and tradition prefer using raw milk, which contains natural bacteria that add depth and unique, complex flavours to the cheese. Raw milk cheese is often associated with artisanal production and small-scale farming, but it carries higher food safety risks and has a shorter shelf life.

Cheese Escape: Unlocking the Grey Key

You may want to see also

Milk source

Milk is the base product used to make cheese, and evidence suggests that about 20% of the final flavours in a cheese come from the milk. The flavour of milk varies depending on what the animals are fed, their breed, and whether the milk is pasteurised or unpasteurised. For example, Ayrshire cow milk has a buttery, rich flavour, which is reflected in the Hafod Cheddar cheese made from it.

The type of milk used also influences the cheese variety. While most cheeses are made using cows' milk, milk from other animals, especially goats and sheep, is also used. Goats' milk cheese is white in colour and has a distinctive flavour. Goats' milk has higher water content than cows' milk, so goats' milk cheeses are usually softer. Sheep's milk, on the other hand, is higher in fat and makes a creamy-textured cheese.

The moisture content of milk is another factor that influences the cheese-making process. Soft cheeses are made by acidifying milk and then draining off the whey, leaving some moisture in the cheese. Hard cheeses, on the other hand, are made by driving out as much moisture as possible through various methods such as pressing, heating, and stacking the curds.

The process of cheesemaking involves removing water from milk, which concentrates the milk's protein, fat, and other nutrients. This removal of water influences the texture and flavour of the resulting cheese. For example, the traditional British method of making hard cheeses involves acidifying milk at a low temperature, stacking and pressing the curds, and then driving out moisture. This process results in a friable texture and sharper savoury flavours found in cheeses such as Cheddar and Lancashire.

Cheese Sauce in Bugsnax: A Tasty Treat

You may want to see also

Bacteria and mould

The variety of cheeses available worldwide, from cheddar to gouda, brie to blue, each boasts its own unique flavour and texture. This distinctiveness is largely due to the presence of bacteria and mould.

During the cheese-making process, specific types of bacteria and mould are added to milk to induce fermentation and create the desired flavour and texture. These microorganisms break down the lactose in the milk, releasing lactic acid, which helps coagulate the milk and form curds. Different types of bacteria and mould will produce different flavours and textures. For example, cheddar is made using a combination of bacteria such as Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactococcus lactis, resulting in a tangy, sharp flavour and firm texture. On the other hand, Brie employs a different combination of bacteria, including Penicillium candidum, which gives it its characteristic soft texture and nutty, buttery flavour.

The ageing process of cheese also plays a significant role in flavour development. As cheese ages, the bacteria and mould continue to grow and ferment, intensifying the flavour and altering the texture. A young cheddar will have a milder flavour and softer texture compared to an aged cheddar, which will have a sharper, more pronounced flavour and a firmer texture. Similarly, blue cheese will have a milder flavour and softer texture when young, developing a stronger, more pungent flavour and crumbly texture with age.

The specific types of bacteria and mould used in the cheese-making process are chosen to achieve the desired flavour and texture profile. For instance, Lactobacillus helveticus is often added to aged Gouda, imparting a pleasant sweet flavour and promoting the growth of tyrosine crystals. Additionally, adjunct microbes are introduced to enhance flavour development. These adjuncts, such as Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria (NSLAB), are not primarily added for acidification but rather to contribute to the complex flavour profile of the cheese. As cheese ages, the population of NSLAB increases while the number of starter cultures decreases, indicating their role in flavour development during ripening.

The environment in which the cheese is produced can also influence the microbial composition and, consequently, the flavour and texture of the cheese. This concept, known as "terroir," encompasses environmental factors such as climate, soil, and local flora and fauna. For example, the milk of cows, goats, or sheep may contain microbes, and additional microbes can be introduced during the milking and cheesemaking process from sources such as straw bedding. Thus, the unique characteristics of a particular cheese can be attributed not only to the specific bacteria and mould used but also to the environmental factors that influence the microbial makeup of the cheese.

The Best Places to Buy Halloumi Cheese

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Processing techniques

The first step in cheese processing involves curd formation, which can be manipulated through "curd washing" to alter the flavour and texture of the final product. Curd washing involves replacing some of the whey with water, resulting in cheeses with a milder flavour and more elastic texture, such as Gouda or Havarti. The moisture content of cheese is a critical factor in preservation and ripening methods, with harder cheeses requiring lower moisture levels achieved through pressing or moulding.

The ripening process is the most crucial stage for flavour development in cheese. During ripening, bacteria metabolise residual lactose into lactic acid, and in the absence of lactose, they utilise proteins as a source of carbon, nitrogen, sulphur, and ATP. This shift in bacterial metabolism during ripening is influenced by low temperatures, high acidity, and salt content, leading to the production of flavour compounds. The specific genera and physiological state of the bacteria also influence the flavour outcomes.

The ageing process further enhances the flavour of cheese by allowing enzymes to break down proteins and fats, creating intricate compounds that shape the cheese's flavour profile. Aged cheeses develop more complex and deep flavours due to the interaction of various compounds formed during ageing. The controlled environment, including temperature and humidity, plays a significant role in the ageing process, with subtle changes affecting the final taste and texture.

Additionally, the type of salt used during cheese processing is essential, as iodised salt can negatively impact flavour and texture. The addition of salt enhances flavour, regulates moisture content, controls bacterial growth, and aids in preservation. The relative casein content (RCC) of the base cheese is another critical factor, influencing the emulsification properties and overall texture of the final product.

Best Places for Chili Cheese Fries

You may want to see also

Ageing

During ageing, cheeses undergo various chemical and biological changes. The culture inside the curd breaks down lactose into lactic acid, and the long protein chains are broken down into smaller amino acid compounds through proteolysis. This process gives aged cheeses their distinctive smoky, fruity, or nutty flavours. The breakdown of proteins and fats in the cheese continues, hardening it and further intensifying its flavours. Additionally, the development of mould, both naturally occurring and introduced through bacterial cultures, adds unique flavours and colours to the cheese.

The environment in which the cheese ages is also essential. Cheesemakers maintain a cool, damp environment with high humidity, usually above 90%, and temperatures around 50 degrees Fahrenheit. These conditions promote the growth of desirable moulds and microbes, enhancing the flavour and texture of the cheese. Some cheeses are aged in specific environments, such as caves, to take advantage of natural moulds like Penicillium Roquefort, which gives Roquefort cheese its distinctive blue veins.

The ageing process also affects the texture of the cheese. Aged cheeses tend to be firmer or crumbly, with a lower moisture content, resulting in a longer shelf life compared to unaged cheeses. The longer ageing process also reduces lactose levels, making aged cheeses more suitable for lactose-intolerant individuals.

The duration of ageing varies depending on the type of cheese. Softer cheeses like Muenster or mild Cheddar require shorter ageing periods, while semi-hard and hard cheeses like sharp Cheddar, Gouda, and Parmesan need longer ageing times. For example, Parmesan is typically aged for a minimum of two years, contributing to its complex flavours and texture.

Real Cheese: Where to Source the Best

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Differences in the origin of the milk, pasteurisation, butterfat content, bacteria and mould, processing techniques, and aging all contribute to the unique flavours of cheese.

The flavour of milk varies depending on the breed of animal it comes from, what the animal is fed, and whether the milk is pasteurised or unpasteurised.

The flavour of cheese develops during the aging process as a result of a series of microbiological, enzymatic, and chemical changes, including proteolysis, lipolysis, and glycolysis.

One example is the process of making washed rind cheese. By frequently washing the rind, the growth of white mould is prevented, and a sticky orange bacterium is encouraged to grow, giving the cheese a distinct flavour and smell.