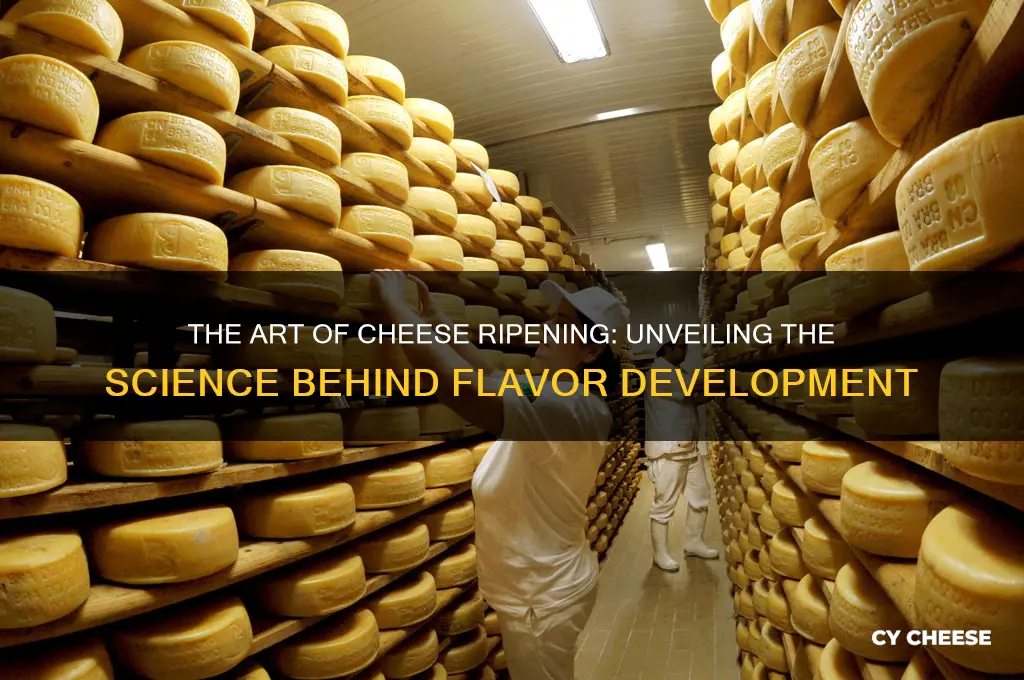

Cheese ripening, also known as cheese aging, is a complex process that transforms fresh curds into flavorful, textured cheeses through the action of bacteria, molds, and enzymes. During ripening, microorganisms break down proteins and fats, releasing amino acids and fatty acids that contribute to the cheese's unique taste and aroma. Additionally, moisture evaporates, concentrating flavors and altering the cheese's texture from soft to hard. Factors such as temperature, humidity, and the type of bacteria or molds used play crucial roles in determining the final characteristics of the cheese. This carefully controlled process can take anywhere from a few weeks to several years, resulting in the diverse array of cheeses enjoyed worldwide.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Microbial Activity | Bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus, Propionibacterium) and molds (e.g., Penicillium) break down milk proteins and fats, producing enzymes like lipases and proteases. |

| Enzymatic Breakdown | Enzymes (endogenous from milk or added during production) hydrolyze proteins (proteolysis) and fats (lipolysis), creating flavor compounds and texture changes. |

| Moisture Loss | Cheese loses moisture over time, concentrating flavors and altering texture (e.g., harder cheeses like Parmesan). |

| pH Changes | Microbial activity lowers pH, affecting protein structure and flavor development (e.g., sharper taste in aged cheeses). |

| Flavor Development | Breakdown of proteins and fats produces amino acids, fatty acids, and other compounds, contributing to complex flavors (e.g., nutty, earthy, or pungent notes). |

| Texture Changes | Proteolysis and moisture loss transform texture from soft and creamy (young cheese) to firm or crumbly (aged cheese). |

| Mold Growth (if applicable) | Surface or internal molds (e.g., in Brie or Blue Cheese) contribute to flavor, aroma, and texture by breaking down curds. |

| Temperature and Humidity | Controlled aging conditions (temperature: 4-15°C, humidity: 80-90%) influence ripening speed and microbial activity. |

| Time | Ripening duration varies by cheese type (e.g., weeks for fresh cheese, months or years for hard cheeses like Cheddar or Parmesan). |

| Salt Content | Salt slows microbial activity, preserves cheese, and influences moisture loss and flavor balance. |

| Oxygen Exposure | Some cheeses (e.g., surface-ripened) require oxygen for mold growth, while others (e.g., wax-coated) are anaerobic. |

| Curd Treatment | Stretching, pressing, or heating curds during production affects final texture and ripening process. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Role of Bacteria and Molds: Microorganisms break down milk proteins and fats, developing flavor and texture

- Effect of Humidity and Temperature: Controlled environments influence moisture loss and microbial activity during aging

- Types of Ripening Processes: Differentiates between surface, internal, and washed-rind ripening methods

- Time and Cheese Variety: Aging duration varies by type, impacting hardness, flavor, and aroma

- Chemical Changes During Ripening: Enzymes transform proteins and fats into complex flavor compounds

Role of Bacteria and Molds: Microorganisms break down milk proteins and fats, developing flavor and texture

Cheese ripening is a complex dance of microbiology, where bacteria and molds take center stage. These microorganisms are the unsung heroes behind the transformation of simple milk into a diverse array of cheeses, each with its unique flavor and texture. The process begins with the breakdown of milk proteins and fats, a task meticulously executed by specific bacteria and molds. For instance, *Lactococcus lactis* and *Streptococcus thermophilus* are commonly used starter cultures that convert lactose into lactic acid, lowering the pH and creating an environment conducive to further microbial activity. This initial step is crucial, as it not only preserves the milk but also sets the stage for the development of complex flavors and textures.

Consider the role of molds in cheeses like Brie or Camembert. *Penicillium camemberti* is introduced to the cheese's surface, where it grows, producing enzymes that break down proteins and fats. This breakdown releases amino acids and fatty acids, which contribute to the cheese's characteristic earthy, nutty flavors. The mold’s activity also affects texture, creating a soft, creamy interior beneath a velvety rind. In contrast, hard cheeses like Cheddar rely on bacteria such as *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, which produces carbon dioxide gas, creating the distinctive eye formation and contributing to a sharper flavor profile. Each microorganism has a specific role, and their interplay determines the cheese's final characteristics.

To harness these microorganisms effectively, cheesemakers must control temperature, humidity, and aging time with precision. For example, surface-ripened cheeses like Brie are aged at 12–15°C (54–59°F) with high humidity to encourage mold growth, while hard cheeses like Parmesan are aged at cooler temperatures (16–20°C or 61–68°F) for longer periods, allowing bacteria to slowly break down proteins and fats. Practical tips include monitoring pH levels—a drop from 6.6 to 5.0 indicates successful lactic acid production—and ensuring proper airflow to prevent unwanted mold growth. Understanding these conditions allows cheesemakers to manipulate the ripening process, tailoring it to achieve desired flavors and textures.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark differences in microbial roles across cheese types. Blue cheeses like Roquefort introduce *Penicillium roqueforti*, which penetrates the cheese, creating veins and a pungent flavor through proteolytic and lipolytic activity. In contrast, washed-rind cheeses like Epoisses use bacteria like *Brevibacterium linens* to develop a sticky, orange rind and a robust, meaty flavor. These examples highlight how specific microorganisms are selected and nurtured to achieve distinct sensory profiles. The takeaway is clear: mastering the role of bacteria and molds is essential for crafting cheese that delights the palate.

Finally, the art of cheese ripening is as much a science as it is a craft. By understanding the specific functions of bacteria and molds, cheesemakers can manipulate the process to create a wide range of products. Whether you're a home cheesemaker or a professional, recognizing the importance of these microorganisms allows for experimentation and innovation. For instance, adjusting the type or concentration of starter cultures can alter flavor intensity, while controlling aging conditions can refine texture. With this knowledge, the possibilities are endless, and the journey from milk to masterpiece becomes a fascinating exploration of microbiology in action.

Does a Cheeseburger Contain Ham? Unraveling the Classic Burger Myth

You may want to see also

Effect of Humidity and Temperature: Controlled environments influence moisture loss and microbial activity during aging

Cheese ripening is a delicate dance between humidity and temperature, each factor playing a pivotal role in shaping the final product. Imagine a wheel of cheddar aging in a cool, damp cellar versus a block of parmesan maturing in a warmer, drier environment. The contrast in texture, flavor, and aroma between these two cheeses highlights the profound impact of controlled environments. Humidity and temperature are not mere background players; they are the directors of the microbial orchestra that transforms fresh curds into complex, flavorful cheeses.

The Role of Humidity: Moisture Loss and Texture

Humidity controls the rate of moisture loss during aging, directly influencing the cheese’s texture. In high-humidity environments (85–95%), cheeses like Brie retain a soft, creamy interior as moisture evaporates slowly. Conversely, low humidity (50–60%) accelerates drying, ideal for hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano, which develop a granular, crumbly texture. For example, a humidity drop below 50% can cause excessive moisture loss in semi-hard cheeses like Gouda, leading to cracks and uneven ripening. To maintain optimal conditions, use a hygrometer and adjust humidity with damp cloths or dehumidifiers. Pro tip: For home aging, store cheese in a wine fridge with a water tray to stabilize humidity.

Temperature’s Impact: Microbial Activity and Flavor Development

Temperature dictates the pace and type of microbial activity, driving flavor development. Cool temperatures (4–10°C) slow ripening, allowing complex flavors to emerge gradually, as seen in Alpine cheeses like Gruyère. Warmer conditions (12–16°C) accelerate bacterial and fungal growth, ideal for surface-ripened cheeses like Camembert. However, temperatures above 18°C can lead to ammonia flavors or spoilage. For instance, aging a blue cheese like Roquefort at 8°C encourages Penicillium roqueforti growth without overheating. Practical advice: Monitor temperature daily, especially during seasonal changes, and use insulated aging spaces to maintain consistency.

Balancing Act: Humidity and Temperature Synergy

The interplay between humidity and temperature is critical. A high-temperature, low-humidity environment can dry out cheese prematurely, while high humidity in warm conditions may foster unwanted mold growth. For example, a semi-soft cheese like Muenster requires 80% humidity at 10°C to develop its signature supple texture and tangy flavor. Conversely, a hard cheese like Pecorino needs 60% humidity at 12°C to harden properly. To achieve balance, adjust humidity first, then fine-tune temperature. Caution: Avoid sudden changes, as they can shock the cheese’s microbial ecosystem.

Practical Application: Creating Controlled Environments

For home cheesemakers, replicating professional aging conditions is achievable with simple tools. Use a refrigerator with adjustable shelves and a humidity tray for soft cheeses, or a garage with a space heater and dehumidifier for harder varieties. Aim for a 5°C fluctuation range to mimic natural aging caves. For example, age a batch of cheddar at 10°C and 70% humidity for 6 months, flipping the wheel weekly to ensure even moisture distribution. Takeaway: Consistency is key—small deviations in humidity or temperature can alter the cheese’s character dramatically.

By mastering the interplay of humidity and temperature, cheesemakers can craft products with precision, ensuring each wheel or block reaches its full potential. Whether aging a delicate Brie or a robust Pecorino, controlled environments are the unsung heroes of the ripening process.

Delicious Charcuterie Board: Olives, Salami, and Cheeses Explained

You may want to see also

Types of Ripening Processes: Differentiates between surface, internal, and washed-rind ripening methods

Cheese ripening is a complex art, and the method employed significantly influences the final product's texture, flavor, and aroma. Three primary ripening processes dominate the craft: surface, internal, and washed-rind ripening. Each technique fosters distinct microbial communities, resulting in unique sensory profiles.

Surface ripening involves cultivating mold or bacteria on the cheese's exterior, which gradually penetrates the interior. This method is commonly used for cheeses like Brie and Camembert. The process begins by inoculating the cheese surface with specific molds, such as Penicillium camemberti, which grow and produce enzymes that break down the cheese's structure. As the mold grows, it creates a bloomy, edible rind, and the interior becomes soft and creamy. The ripening time varies, but typically, Brie and Camembert are aged for 3-4 weeks at temperatures between 12-15°C (54-59°F) with a relative humidity of 90-95%. To achieve optimal results, maintain consistent temperature and humidity levels, and regularly turn the cheeses to ensure even ripening.

In contrast, internal ripening relies on bacteria or molds incorporated into the cheese curd before pressing and molding. This method is characteristic of cheeses like Cheddar and Gouda. The bacteria, often lactic acid bacteria or propionic bacteria, produce gases and acids that create eyes (holes) and contribute to flavor development. For instance, in Cheddar production, the curd is heated, cut, and stacked to encourage whey expulsion, followed by milling, salting, and pressing. The cheese is then aged for 2-24 months, depending on the desired sharpness. During aging, the bacteria continue to metabolize, producing lactic acid and other compounds that contribute to the cheese's distinctive tangy flavor and crumbly texture.

Washed-rind ripening is a more labor-intensive process, involving regular washing of the cheese's surface with solutions like brine, beer, or wine. This method promotes the growth of Brevibacterium linens, a bacteria responsible for the distinct orange-red rind and pungent aroma of cheeses like Époisses and Limburger. The washing process creates a humid environment, encouraging bacterial growth and enzyme activity. As the bacteria break down the cheese's surface, they produce ammonia and other compounds that contribute to the cheese's strong flavor and aroma. Washed-rind cheeses are typically aged for 4-8 weeks, during which they are washed every 2-3 days. To prevent the growth of undesirable molds, maintain proper sanitation and ensure the washing solution is free from contaminants.

The choice of ripening method depends on the desired cheese characteristics, with each technique offering distinct advantages. Surface ripening provides a delicate, creamy texture and mild flavor, while internal ripening results in a firmer texture and more complex flavor profile. Washed-rind ripening, on the other hand, produces a bold, pungent cheese with a distinctive appearance. By understanding these ripening processes, cheesemakers can craft a diverse range of cheeses, each with its unique sensory qualities. When experimenting with these methods, consider factors like temperature, humidity, and microbial cultures to achieve the desired outcome, and don't be afraid to adjust the process to suit your specific needs and preferences.

Aging Cheese, Growing Business: Launching a Successful Cheese Company

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Time and Cheese Variety: Aging duration varies by type, impacting hardness, flavor, and aroma

Cheese aging is a delicate dance between time and transformation, where each variety follows its own unique rhythm. From the moment curds are formed, the clock starts ticking, dictating the texture, flavor, and aroma that will define the final product. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella or chèvre are rushed to market, their aging measured in days or weeks, preserving a soft, mild character. In contrast, hard cheeses such as Parmigiano-Reggiano or Cheddar are aged for months or even years, developing complex flavors and a firm, crumbly texture. This diversity in aging duration is not arbitrary but a precise science, tailored to each cheese’s intended identity.

Consider the aging process as a recipe where time is the key ingredient. For semi-soft cheeses like Gruyère, aging typically spans 3 to 12 months, allowing the wheels to develop a nutty flavor and slightly grainy texture. During this period, enzymes break down proteins and fats, while bacteria and molds contribute to flavor development. Hard cheeses, on the other hand, require a longer commitment—Cheddar ages for 6 months to 2 years, and Parmesan for a minimum of 12 months, often extending to 36 months. The longer the aging, the more moisture evaporates, concentrating flavors and hardening the texture. This progression is not linear; each cheese has an optimal aging window, beyond which it may become overly sharp or dry.

Aging also introduces practical considerations for cheesemakers and consumers alike. For instance, longer-aged cheeses are more expensive due to extended storage time, labor, and higher moisture loss, which reduces yield. However, the payoff is a product with unparalleled depth and complexity. For home enthusiasts, understanding aging times can guide selection and storage. Fresh cheeses should be consumed within days, while aged cheeses benefit from proper humidity and temperature control to prevent drying or spoilage. A cheese’s age is often indicated on the label, offering a clue to its flavor profile—young cheeses are mild and creamy, while older ones are bold and pungent.

Comparing varieties highlights the dramatic impact of aging. Take Gouda, for example: young Gouda (aged 1–6 months) is mild and buttery, ideal for sandwiches, while aged Gouda (12–24 months) becomes caramelized and crystalline, perfect for pairing with wine. Similarly, blue cheeses like Stilton or Roquefort rely on shorter aging (2–6 months) to allow mold cultures to develop their signature veins and sharp, tangy flavors. These contrasts underscore how aging duration is not just a measure of time but a tool for crafting distinct sensory experiences.

In essence, the relationship between time and cheese variety is a masterclass in precision and patience. Each cheese’s aging duration is a deliberate choice, shaping its hardness, flavor, and aroma into a unique expression of its type. Whether you’re a cheesemaker, a chef, or a connoisseur, understanding this interplay allows you to appreciate—and manipulate—the transformative power of time. So, the next time you savor a slice of cheese, consider the months or years of aging that brought it to your plate, and let that knowledge deepen your enjoyment.

Does Lasagna Have Ricotta Cheese? Unraveling the Classic Recipe Debate

You may want to see also

Chemical Changes During Ripening: Enzymes transform proteins and fats into complex flavor compounds

Cheese ripening is a symphony of chemical transformations, orchestrated by enzymes that break down proteins and fats into the complex molecules responsible for flavor. This process, akin to the slow fermentation of wine or the aging of meat, relies on a delicate balance of time, temperature, and microbial activity. Enzymes, both from the milk itself and introduced through bacterial cultures, act as molecular scissors, cleaving large, flavorless molecules into smaller, volatile compounds that tantalize the palate.

Consider the breakdown of casein, the primary protein in milk. During ripening, proteolytic enzymes like rennet and those produced by bacteria such as *Lactococcus lactis* hydrolyze casein into peptides and amino acids. These smaller molecules contribute to the savory, umami notes in aged cheeses like Parmesan. For instance, the amino acid glutamate, released during this process, is a key player in the rich, brothy flavor profile of long-aged cheeses. Similarly, lipases target milk fats, breaking down triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol. These compounds add sharpness and complexity, as seen in the tangy bite of a well-aged cheddar.

The interplay of enzymes and substrates is not random but highly specific. For example, penicillium molds in blue cheeses like Roquefort produce enzymes that degrade fats and proteins, creating distinct, pungent flavors. In contrast, the surface molds of Brie release enzymes that break down the cheese’s exterior, contributing to its creamy texture and earthy aroma. Temperature and humidity play critical roles here: a cooler environment (around 50°F or 10°C) slows enzymatic activity, allowing for gradual flavor development, while higher moisture levels can accelerate surface ripening.

Practical control of these processes is essential for cheesemakers. Adjusting the pH of the curd, for instance, can influence enzyme activity—a lower pH (more acidic) can enhance proteolysis, while a higher pH favors lipolysis. Adding specific bacterial cultures, such as *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* in Swiss cheese, introduces enzymes that produce carbon dioxide (creating the characteristic eye formation) and propionic acid, contributing to its nutty flavor. Home cheesemakers can experiment with aging conditions: storing cheese in a wine fridge at 55°F (13°C) with 85% humidity encourages slow, even ripening, while wrapping it in cheese paper allows for breathability without drying out.

The takeaway is clear: enzymes are the unsung heroes of cheese ripening, transforming simple milk components into a tapestry of flavors. Understanding their role allows both artisans and enthusiasts to manipulate time, temperature, and microbial activity to craft cheeses with desired profiles. Whether you’re aging a wheel of Gouda or experimenting with homemade camembert, recognizing the enzymatic dance at play empowers you to guide the transformation from bland curd to flavorful masterpiece.

Identifying Unpasteurized Cheese: Key Signs and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese ripening is the process by which cheese matures and develops its flavor, texture, and aroma through the action of bacteria, molds, and enzymes over time.

Cheese ripens through the activity of microorganisms (bacteria and molds) and enzymes present in the cheese. These break down proteins and fats, creating complex flavors and altering the texture.

Ripening time varies depending on the type of cheese. Soft cheeses may ripen in a few weeks, while hard cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan can take several months to years.

Factors include temperature, humidity, salt content, pH levels, and the type of bacteria or molds used. Proper storage conditions are crucial for consistent ripening.

Yes, over-ripening can cause cheese to become overly pungent, dry, or develop off-flavors. The ideal ripening time depends on the cheese variety and desired characteristics.