Cheese is a beloved and versatile food that has been consumed for thousands of years, but its edibility stems from a fascinating process of fermentation and preservation. Made primarily from milk, cheese undergoes a transformation where bacteria and enzymes break down lactose into lactic acid, curdling the milk and separating it into curds and whey. The curds are then pressed, aged, and sometimes treated with additional bacteria or molds, which not only enhance flavor but also act as natural preservatives. This aging process, which can range from a few weeks to several years, further reduces moisture content and creates an environment inhospitable to harmful pathogens, ensuring cheese remains safe to eat. Additionally, the high fat and protein content in cheese slows spoilage, making it a durable and nutritious food source. From fresh mozzarella to aged cheddar, the science behind cheese production ensures its edibility, allowing it to be enjoyed in countless culinary traditions worldwide.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Nutritional Composition | High in protein, fat, calcium, phosphorus, and vitamins (A, B12, D, K2) |

| Fermentation Process | Fermented by lactic acid bacteria, which preserves milk and enhances flavor |

| Low Lactose Content | Most lactose is converted to lactic acid during fermentation, making it tolerable for many lactose-intolerant individuals |

| Texture and Consistency | Varies from soft (e.g., Brie) to hard (e.g., Parmesan), depending on moisture content and aging |

| Flavor Profile | Diverse flavors due to bacterial cultures, aging, and added ingredients (e.g., herbs, spices, molds) |

| Shelf Life | Extended shelf life due to fermentation, salting, and aging processes |

| Digestibility | Easier to digest than milk due to reduced lactose and broken-down proteins |

| Versatility | Edible raw, cooked, melted, or as an ingredient in various dishes |

| Preservation Method | Salt is often added to inhibit bacterial growth and preserve the cheese |

| Microbial Safety | Fermentation and aging reduce harmful bacteria, making it safe for consumption |

| Allergenicity | Generally safe for most people, though rare allergies to milk proteins exist |

| Cultural Significance | Widely consumed globally, with thousands of varieties across cultures |

Explore related products

$13.07 $16.95

$19.98 $27.99

What You'll Learn

- Milk Source: Cheese is made from milk of cows, goats, sheep, or buffalo, which is edible

- Coagulation Process: Enzymes or acids curdle milk, separating solids (curds) from liquids (whey)

- Aging and Ripening: Controlled conditions develop flavor, texture, and safety over time

- Preservation Methods: Salt, heat, or bacteria inhibit spoilage, extending shelf life

- Safety Standards: Pasteurization and hygiene ensure cheese is free from harmful pathogens

Milk Source: Cheese is made from milk of cows, goats, sheep, or buffalo, which is edible

Cheese begins with milk, a nutrient-rich liquid naturally produced by mammals to nourish their young. Cows, goats, sheep, and buffalo are the primary sources for cheese production, each offering milk with distinct compositions that influence flavor, texture, and yield. Cow’s milk, the most common, contains approximately 3.5–5% fat and 3.3% protein, making it ideal for versatile cheeses like cheddar and mozzarella. Goat’s milk, with its lower fat globules and higher digestibility, produces tangy, slightly sweet cheeses such as chèvre. Sheep’s milk, richer in fat (6–8%) and protein, yields dense, creamy cheeses like pecorino and manchego. Buffalo milk, with its 7–8% fat content, is the base for luxurious mozzarella di bufala. These variations in milk composition directly shape the character of the cheese, proving that the source matters as much as the process.

Selecting the right milk source is both an art and a science. For home cheesemakers, understanding the milk’s fat and protein content is crucial. For example, high-fat milk like buffalo or sheep is better suited for stretched cheeses, while lower-fat goat’s milk works well for fresh, soft varieties. Pasteurized milk is safe and widely available, but raw milk, though riskier, can impart deeper flavors due to its intact enzymes and bacteria. However, raw milk must be handled meticulously to avoid contamination. A practical tip: if using store-bought milk, opt for whole milk to ensure sufficient fat for proper curd formation. Always source milk from reputable suppliers to guarantee freshness and quality, as off-flavors in milk will carry over into the cheese.

From a nutritional standpoint, the milk source also determines the cheese’s health profile. Cow’s milk cheeses are rich in calcium and vitamin B12, while goat’s milk cheeses are easier on lactose-intolerant individuals due to their lower lactose content. Sheep’s milk cheeses pack a higher calorie and protein punch, making them more satiating. Buffalo milk cheeses, though indulgent, provide conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a compound linked to potential health benefits. For those monitoring fat intake, goat or cow’s milk cheeses offer lighter options. Pairing cheese with complementary foods—such as nuts for healthy fats or fruit for fiber—can balance its richness. Moderation is key; a 1-ounce (28-gram) serving is a standard portion to enjoy without overindulging.

The cultural and culinary significance of milk sources cannot be overstated. Each animal’s milk reflects its environment and diet, creating regional cheese varieties with unique identities. French chèvre, Italian pecorino, and Greek feta are not just cheeses but expressions of their origins. For instance, sheep grazing on Mediterranean herbs impart subtle flavors to their milk, which carry through to the cheese. This connection to terroir makes cheese a storytelling medium, linking consumers to traditions and landscapes. When selecting cheese, consider its milk source not just for taste but also to support sustainable farming practices and preserve biodiversity. Choosing cheeses made from pasture-raised animals ensures ethical production and richer flavors.

In conclusion, the milk source is the foundation of cheese’s edibility, dictating its flavor, texture, and nutritional value. Whether you’re a cheesemaker, a connoisseur, or a casual consumer, understanding this relationship enhances appreciation and informed choices. Experiment with different milk-based cheeses to discover how each source contributes to the final product. For practical exploration, start with a simple recipe like ricotta using cow’s milk, then venture into goat or sheep’s milk for more complex flavors. By valuing the milk source, you not only enjoy cheese but also honor the animals and artisans behind it.

Where's American Cheese? Unraveling the Mystery of Its Store Absence

You may want to see also

Coagulation Process: Enzymes or acids curdle milk, separating solids (curds) from liquids (whey)

The transformation of milk into cheese begins with a delicate dance of chemistry, where enzymes or acids act as choreographers, orchestrating the separation of solids from liquids. This coagulation process is the cornerstone of cheese-making, turning a fluid substance into a solid, edible delight. At its core, coagulation involves the curdling of milk, a reaction that causes proteins to clump together, forming curds, while the remaining liquid, known as whey, is drained away. This fundamental step not only alters the texture of milk but also sets the stage for the development of cheese’s unique flavors and structures.

Enzymes, particularly rennet, are commonly used to initiate coagulation in traditional cheese-making. Derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals, rennet contains chymosin, a protease that specifically targets kappa-casein, a protein in milk. When added in precise amounts—typically 0.02 to 0.05% of the milk’s weight—rennet causes the milk to curdle within 30 to 60 minutes, depending on temperature and acidity. This enzymatic action is highly efficient, producing a clean break between curds and whey, which is essential for cheeses like Cheddar or Parmesan. For those seeking vegetarian alternatives, microbial enzymes, such as those from *Mucor miehei*, offer a comparable effect, though they may require slightly different handling due to variations in activity.

Acids, on the other hand, provide a simpler, more accessible method of coagulation, often used in fresh cheeses like cottage cheese or queso fresco. Common acidifying agents include vinegar, lemon juice, or citric acid, which lower the milk’s pH, causing proteins to denature and coagulate. To achieve optimal results, add 1 to 2 tablespoons of vinegar or lemon juice per gallon of milk, stirring gently until the mixture reaches a pH of around 4.6. This method is faster—curdling occurs within minutes—but produces softer, more delicate curds and a higher whey yield. While acid-coagulated cheeses lack the complexity of enzyme-driven varieties, they are ideal for quick, homemade cheese projects.

Understanding the coagulation process allows cheese-makers to manipulate texture, flavor, and yield. Enzymatic coagulation, with its precision and control, is favored for aged and hard cheeses, where a firm curd structure is crucial. Acid coagulation, while less refined, offers simplicity and speed, making it perfect for fresh, soft cheeses. Both methods, however, share a common goal: transforming milk into a stable, edible form that can be further processed into the diverse array of cheeses we enjoy. By mastering coagulation, one gains the foundation for crafting cheese that is not only safe to eat but also a testament to the artistry of food science.

Does Processed Cheese Burn? Unraveling the Melting Mystery in Cooking

You may want to see also

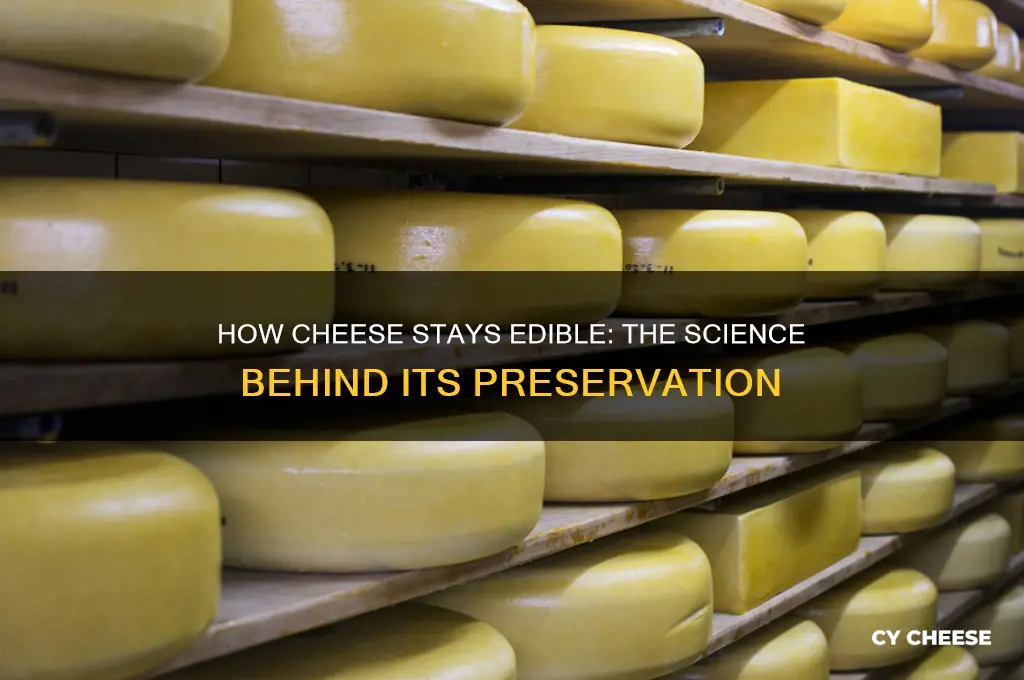

Aging and Ripening: Controlled conditions develop flavor, texture, and safety over time

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, owes its diverse flavors, textures, and safety to the intricate processes of aging and ripening. These processes are not merely passive waiting periods but highly controlled environments where science and art converge. By manipulating temperature, humidity, and microbial activity, cheesemakers transform fresh curds into complex, edible masterpieces.

Consider the role of time in developing flavor. During aging, enzymes break down proteins and fats, releasing amino acids and fatty acids that contribute to the cheese’s unique taste profile. For instance, a young cheddar aged 6 months will have a milder, sharper flavor compared to a 24-month vintage cheddar, which boasts deep, nutty, and sometimes crystalline notes. Humidity levels are equally critical; a relative humidity of 85–90% is ideal for most cheeses, preventing excessive moisture loss while allowing proper surface mold growth. Too dry, and the cheese becomes brittle; too damp, and it risks spoilage.

Texture, another hallmark of aged cheese, emerges from moisture loss and microbial activity. Hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano are aged for 12–36 months, during which they lose up to 30% of their moisture, resulting in a dense, granular structure. In contrast, semi-soft cheeses like Gruyère develop a supple yet firm texture after 5–12 months of aging, thanks to the interplay of bacteria and molds. Practical tip: when storing aged cheese at home, wrap it in wax or parchment paper to maintain humidity without suffocating the rind.

Safety is a silent but vital outcome of aging and ripening. Controlled conditions inhibit harmful pathogens while fostering beneficial bacteria. For example, the pH of cheese typically drops below 5.0 during aging, creating an environment hostile to most spoilage organisms. Additionally, surface molds on cheeses like Brie act as natural preservatives, competing with unwanted microbes. However, caution is key: improper aging temperatures (above 15°C for most cheeses) can lead to off-flavors or even health risks.

In essence, aging and ripening are not just steps in cheesemaking—they are transformative journeys. By mastering these controlled conditions, cheesemakers elevate raw ingredients into edible art, balancing flavor, texture, and safety with precision. Whether you’re a connoisseur or a casual consumer, understanding this process deepens your appreciation for every bite.

Red Meat vs. Cheese: Which Raises Cholesterol Levels More?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.95 $22.95

Preservation Methods: Salt, heat, or bacteria inhibit spoilage, extending shelf life

Cheese, a beloved staple in many diets, owes its longevity to preservation methods that combat spoilage. Among these, salt, heat, and bacteria are the unsung heroes, each playing a distinct role in extending shelf life. Salt, for instance, is a natural preservative that draws moisture out of cheese, creating an environment hostile to spoilage-causing microorganisms. A typical hard cheese like Parmesan contains around 1.5 grams of salt per ounce, a concentration that not only enhances flavor but also inhibits bacterial growth. This method, known as dry salting, is particularly effective in aged cheeses, where salt migrates through the curds over time, ensuring even preservation.

Heat treatment, another critical preservation technique, is applied during the cheese-making process. Pasteurization, which involves heating milk to 161°F (72°C) for 15 seconds, destroys harmful pathogens while preserving beneficial bacteria essential for fermentation. This step is crucial in soft cheeses like Brie, where the risk of contamination is higher due to higher moisture content. Ultra-high temperature (UHT) treatment, though less common in artisanal cheese production, offers even greater microbial reduction, significantly extending shelf life but at the cost of some flavor complexity.

Bacteria, often viewed as a culprit in spoilage, are paradoxically a key player in cheese preservation. Starter cultures like *Lactococcus lactis* and *Streptococcus thermophilus* ferment lactose into lactic acid, lowering the pH of cheese and creating an acidic environment that deters spoilage organisms. In aged cheeses, secondary bacteria and molds, such as *Penicillium camemberti* in Camembert, further protect the cheese by producing antimicrobial compounds. These microbial communities not only preserve the cheese but also contribute to its unique texture and flavor profile.

Practical application of these methods requires precision. For home cheese-making, adding 2-3% salt by weight to the curds is a good starting point, though this varies by cheese type. When using heat, ensure accurate temperature control to avoid denaturing proteins or killing beneficial bacteria. For bacterial preservation, maintain optimal fermentation conditions—typically 86-104°F (30-40°C)—and monitor pH levels to ensure the process proceeds correctly. Combining these methods strategically can yield cheeses with extended shelf lives, from weeks to years, without compromising quality.

In summary, the edibility of cheese over extended periods is a testament to the ingenuity of preservation methods. Salt dehydrates and inhibits microbes, heat eliminates pathogens, and bacteria create protective environments. Each method, when applied with care, not only safeguards cheese but also enhances its sensory qualities. Whether crafting cheese at home or selecting it from a market, understanding these techniques empowers consumers to appreciate and preserve this timeless food effectively.

Exploring the Unique Flavors and Origins of Mono Cheese Varieties

You may want to see also

Safety Standards: Pasteurization and hygiene ensure cheese is free from harmful pathogens

Cheese, a beloved food worldwide, relies heavily on safety standards to remain edible and safe for consumption. At the heart of these standards are pasteurization and hygiene practices, which work together to eliminate harmful pathogens that could otherwise render cheese dangerous. Pasteurization, a process named after Louis Pasteur, involves heating milk to a specific temperature for a set duration to kill bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms. For instance, the FDA mandates that milk be heated to at least 161°F (71.7°C) for 15 seconds to ensure safety. This process is critical in cheese production, as it eliminates pathogens like *Listeria monocytogenes* and *Salmonella*, which can cause severe foodborne illnesses. Without pasteurization, these pathogens could thrive in the cheese’s nutrient-rich environment, posing a significant health risk to consumers.

Hygiene practices complement pasteurization by preventing contamination at every stage of cheese production. From milking equipment to aging rooms, maintaining cleanliness is non-negotiable. For example, dairy farms must sanitize milking machines daily and ensure that workers follow strict handwashing protocols. In cheese factories, surfaces that come into contact with cheese, such as molds and cutting tools, must be cleaned and disinfected regularly. Even the air quality in aging rooms is monitored to prevent the growth of mold species that could produce toxins. These measures are particularly crucial for soft cheeses, which are more susceptible to contamination due to their higher moisture content. By adhering to stringent hygiene standards, producers minimize the risk of reintroducing pathogens after pasteurization, ensuring the final product remains safe.

The combination of pasteurization and hygiene is especially vital for vulnerable populations, such as pregnant women, young children, and the elderly, who are more susceptible to foodborne illnesses. For instance, *Listeria* infections during pregnancy can lead to miscarriage or premature delivery, while *E. coli* contamination can cause severe complications in children. Pasteurized cheese significantly reduces these risks, making it a safer option for these groups. However, it’s essential to note that not all cheeses are pasteurized. Traditional, raw-milk cheeses, while prized for their flavor, carry a higher risk of contamination. Consumers should look for labels indicating pasteurization or consult with cheesemongers to make informed choices.

Despite the effectiveness of pasteurization and hygiene, no system is foolproof. Recalls still occur, often due to lapses in these safety measures. For example, a 2019 outbreak of *Listeria* linked to soft cheese sickened multiple people across several states, highlighting the importance of continuous vigilance. To further enhance safety, some producers employ additional techniques, such as using starter cultures that outcompete harmful bacteria or adding preservatives like natamycin to inhibit mold growth. Consumers can also play a role by storing cheese properly—refrigerating it below 40°F (4°C) and consuming it by the expiration date. By understanding and appreciating these safety standards, cheese lovers can enjoy their favorite varieties with confidence, knowing that every bite has been safeguarded against harm.

Cheese on the Face: Unraveling the Quirky Beauty Trend

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese is edible because the milk is transformed through a process called curdling, where enzymes or acids are added to separate milk into curds (solids) and whey (liquid). The curds are then processed, aged, and preserved, making them safe and enjoyable to eat.

Cheese is designed to resist spoilage through aging, salting, and the growth of beneficial bacteria and molds. These processes lower moisture content, increase acidity, and create an environment hostile to harmful bacteria, extending its shelf life.

Many cheeses with mold (like Brie or Blue Cheese) are safe because the mold is intentionally added and controlled during production. These molds are non-toxic and contribute to flavor and texture, while harmful molds are prevented by proper handling and storage.

Cheese is made by pasteurizing milk (killing harmful bacteria) or through fermentation, which creates an acidic environment that inhibits pathogens. Aging further reduces risks, making cheese a safer dairy product compared to raw milk.

Hard cheeses have low moisture content and high salt levels, which preserve them by preventing bacterial growth. Aging also hardens the texture and intensifies flavor, allowing them to remain edible and delicious for extended periods when stored properly.