Cheese is not grown like a plant but rather crafted through a process that transforms milk into a solid, flavorful food product. The production begins with milk, typically from cows, goats, or sheep, which is heated and combined with bacterial cultures and rennet, an enzyme that coagulates the milk, forming curds and whey. The curds are then cut, stirred, and heated to release moisture, after which they are pressed into molds to shape the cheese. During aging, or ripening, the cheese develops its unique texture and flavor due to the activity of bacteria, molds, and enzymes. This process can take anywhere from a few weeks to several years, depending on the type of cheese being made. Understanding the steps involved in cheese production highlights the intricate balance of science and artistry required to create this beloved dairy product.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Milk Selection: Choosing cow, goat, or sheep milk based on desired cheese flavor and texture

- Coagulation Process: Adding rennet or acid to curdle milk, separating curds from whey

- Curd Handling: Cutting, stirring, and heating curds to release moisture and develop structure

- Aging and Ripening: Storing cheese in controlled environments to develop flavor and texture

- Mold and Bacteria: Introducing specific cultures to create unique flavors and characteristics

Milk Selection: Choosing cow, goat, or sheep milk based on desired cheese flavor and texture

The foundation of any cheese lies in its milk, and the choice between cow, goat, or sheep milk is a pivotal decision that shapes the final product's flavor, texture, and character. Each type of milk brings its own unique composition, influencing the cheese's fat content, protein structure, and natural acidity, which in turn affect how it curdles, ages, and tastes. Cow's milk, for instance, is the most commonly used due to its versatility and mild flavor, making it ideal for a wide range of cheeses, from creamy Camembert to sharp Cheddar. Its higher lactose content and balanced fat-to-protein ratio allow for consistent curd formation and a smooth texture.

Goat’s milk, on the other hand, offers a distinct tanginess and lighter mouthfeel, often preferred in cheeses like Chèvre or aged Gouda. Its lower levels of alpha-s1 casein protein result in a softer curd, which can be both a challenge and an advantage. While goat’s milk cheeses may require more precise handling during coagulation, their bright, citrusy notes and digestibility make them a favorite among those seeking a fresher, more nuanced profile. For cheesemakers, understanding the milk’s natural acidity is key—goat’s milk’s higher acidity can accelerate coagulation, so adjusting rennet dosage (typically 1.5–2.0 mL per gallon) is essential to avoid a crumbly texture.

Sheep’s milk stands out for its richness, with nearly double the fat and protein content of cow’s milk, making it perfect for indulgent, full-bodied cheeses like Pecorino Romano or Manchego. Its higher solids yield a firmer curd and a more concentrated flavor, often described as nutty or earthy. However, this richness demands careful temperature control during pasteurization (ideally 63–65°C for 30 minutes) to prevent scorching. Sheep’s milk’s lower cholesterol content compared to cow’s milk also appeals to health-conscious consumers, though its higher cost limits its use to specialty cheeses.

When selecting milk, consider the desired cheese’s aging process. Cow’s milk cheeses often benefit from longer aging, developing complex flavors over months or years. Goat’s milk cheeses, with their fresher profile, are typically consumed younger, though some aged varieties showcase their unique tanginess. Sheep’s milk cheeses, rich in solids, can withstand extended aging, intensifying their flavor without becoming overly hard. Practical tip: For home cheesemakers, start with cow’s milk for its forgiving nature, then experiment with goat or sheep’s milk to explore more distinctive flavors.

Ultimately, milk selection is an art that balances science and sensory goals. Cow’s milk offers reliability, goat’s milk brings vibrancy, and sheep’s milk delivers luxury. By understanding each milk’s properties and adjusting techniques accordingly, cheesemakers can craft cheeses that not only meet but exceed expectations, turning a simple ingredient into a masterpiece.

Wendy's Nacho Cheese Burger: Ingredients, Toppings, and Flavor Explained

You may want to see also

Coagulation Process: Adding rennet or acid to curdle milk, separating curds from whey

The transformation of milk into cheese begins with a critical step: coagulation. This process involves altering the milk’s structure to separate it into curds (solid) and whey (liquid). Two primary agents achieve this: rennet and acid. Rennet, derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals or produced through microbial fermentation, contains enzymes that target kappa-casein proteins in milk, destabilizing the micelles and causing them to clump together. Acid, such as citric acid or vinegar, lowers the milk’s pH, denaturing proteins and forcing them to coagulate. The choice between rennet and acid depends on the desired cheese type; rennet produces a firmer curd ideal for hard cheeses like cheddar, while acid yields a softer curd suited for fresh cheeses like ricotta.

To execute the coagulation process effectively, precision is key. For rennet, a typical dosage ranges from 1/8 to 1/4 teaspoon per gallon of milk, though this varies by brand and milk type. Add the rennet diluted in cool, non-chlorinated water to milk heated to 86–100°F (30–38°C), depending on the cheese variety. Stir gently for 1–2 minutes, then let the mixture rest for 10–60 minutes until a clean break is achieved—a clear separation between curds and whey when the surface is cut. For acid coagulation, add 1–2 tablespoons of citric acid diluted in water to cold milk, stirring until the curds form and whey becomes translucent. This method is faster, often taking 5–10 minutes, but requires careful monitoring to avoid over-acidification, which can lead to bitter flavors.

A comparative analysis reveals the distinct outcomes of rennet and acid coagulation. Rennet-coagulated curds are elastic, smooth, and retain more moisture, making them ideal for aged cheeses. Acid-coagulated curds are crumbly, grainy, and expel whey more readily, perfect for fresh, quick-to-consume cheeses. For example, cheddar relies on rennet for its dense texture, while paneer uses acid for its soft, crumbly consistency. Understanding these differences allows cheesemakers to tailor the process to the final product’s requirements, ensuring both texture and flavor align with expectations.

Practical tips can enhance the coagulation process. Always use a thermometer to monitor milk temperature, as deviations can hinder enzyme activity or protein denaturation. For rennet, store it in a cool, dark place to preserve its potency, and avoid direct contact with metal, which can degrade the enzymes. When using acid, test the pH with strips to ensure it reaches the optimal range of 6.0–6.6 for curdling. Finally, handle curds gently during separation to avoid breaking them, as this can affect the cheese’s final texture. Mastery of these techniques transforms coagulation from a mere step into an art, laying the foundation for cheese’s diverse forms and flavors.

Does Beer Cheese Contain Beer? Unraveling the Cheesy Mystery

You may want to see also

Curd Handling: Cutting, stirring, and heating curds to release moisture and develop structure

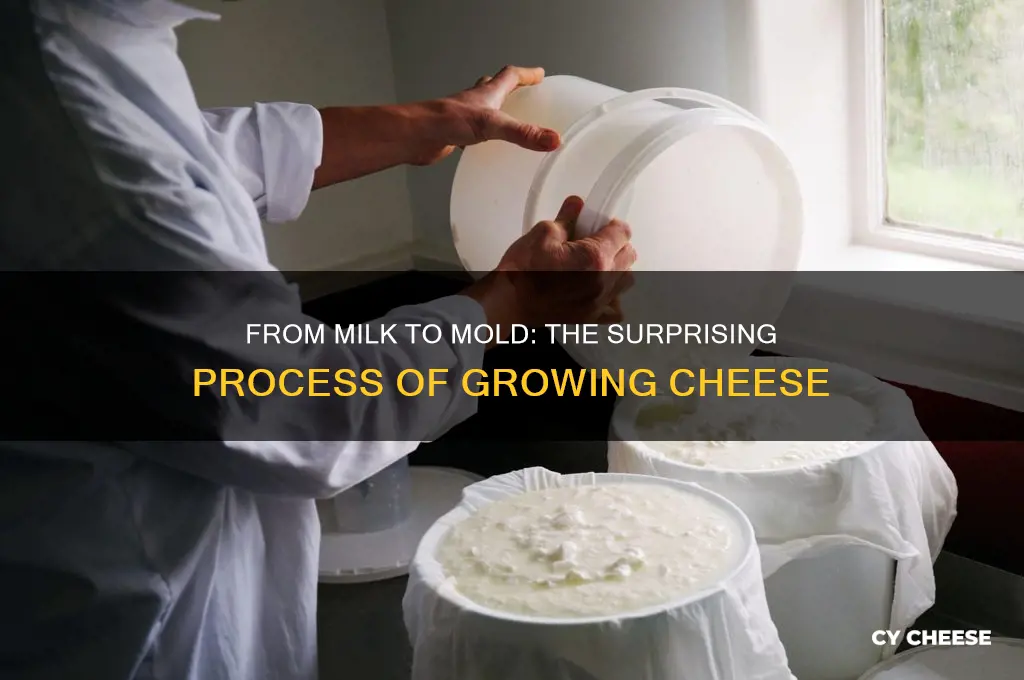

The moment curds form in the cheese-making process, they resemble a delicate, custard-like mass, holding onto whey like a sponge. This is where curd handling becomes critical—a series of precise actions that transform this fragile gel into the foundation of cheese. Cutting, stirring, and heating are not mere steps but calculated maneuvers to release moisture and build the structure that defines texture and flavor. Each action must be timed and executed with care, as too much force can shatter the curds, while too little leaves them weak and watery.

Consider the cutting of curds, often done with long-bladed knives or wires. The goal is to create uniform pieces, typically ranging from pea-sized for hard cheeses like Cheddar to larger chunks for softer varieties like Mozzarella. The size dictates how quickly whey drains and how tightly the curds knit together. For instance, smaller cuts expose more surface area, accelerating moisture loss and creating a firmer texture. This step is both art and science, requiring the cheesemaker to assess the curd’s consistency and adjust accordingly—a too-soft curd may need a gentler approach, while a firmer one can withstand more aggressive cutting.

Stirring follows cutting, a step often overlooked but vital for even moisture release and temperature control. The curds are carefully agitated, preventing them from matting together and ensuring whey drains uniformly. In some traditions, like Cheddar making, this is done with a vigorous "cheddaring" process, where curds are stacked, turned, and cut repeatedly to expel whey and develop acidity. The rhythm and duration of stirring vary by cheese type; for example, a brief, gentle stir suits fresh cheeses, while prolonged agitation is key for aged varieties. Temperature plays a silent role here—curds stirred at higher temperatures (around 35-40°C) release moisture faster but risk becoming tough if overheated.

Heating curds is the final act in this trilogy, a step that consolidates texture and flavor. As curds are warmed, their proteins shrink, squeezing out remaining whey and tightening the structure. This is where the line between success and failure is thinnest. A mere 1-2°C difference can mean the difference between a smooth melt and a rubbery bite. For semi-hard cheeses, curds are heated to around 38-45°C, while harder cheeses like Parmesan may reach 50-55°C. The curds must be monitored constantly, as overheating can cause irreversible damage, turning them grainy or bitter.

Mastering curd handling is about understanding the interplay of force, time, and temperature. It’s a skill honed through practice, where intuition meets precision. For the home cheesemaker, the takeaway is clear: respect the curd’s fragility, observe its cues, and adjust your actions accordingly. Whether crafting a creamy Camembert or a sharp Cheddar, the way you cut, stir, and heat will determine not just the outcome but the character of the cheese itself.

Dating's Like Cheese: Aging, Complex, and Sometimes Smelly

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Aging and Ripening: Storing cheese in controlled environments to develop flavor and texture

Cheese aging, or ripening, is a transformative process where time, temperature, and humidity work in harmony to elevate a simple curd into a complex, flavorful masterpiece. This delicate dance occurs in controlled environments, often called aging rooms or caves, where conditions are meticulously monitored to coax out desired textures and tastes. Imagine a young cheddar, firm and mild, gradually developing a crumbly texture and sharp tang over months of careful aging. This is the magic of ripening, a process as much art as science.

A crucial factor in aging is temperature. Most cheeses thrive in cool environments, typically between 45°F and 55°F (7°C and 13°C). Warmer temperatures accelerate ripening but can lead to undesirable flavors and textures. Humidity is equally vital, with levels often maintained between 80% and 95%. This moisture prevents the cheese from drying out while allowing the growth of beneficial molds and bacteria that contribute to flavor development. For example, the distinctive blue veins in Stilton are the result of Penicillium roqueforti mold, which flourishes in these controlled conditions.

The aging process isn't a one-size-fits-all affair. Different cheeses require specific timelines and conditions. A young, fresh cheese like mozzarella might only need a few days to a week, while a hard cheese like Parmigiano-Reggiano can age for over a year, developing its signature granular texture and nutty flavor. During this time, cheeses are often turned and brushed with brine or mold cultures to encourage even ripening and prevent spoilage.

The art of aging lies in knowing when a cheese has reached its peak. Affineurs, the masters of cheese aging, use their senses to assess readiness. They tap the cheese, listening for a change in sound that indicates desired moisture loss. They smell for complex aromas, from earthy and nutty to fruity and pungent. Finally, they taste, evaluating texture and flavor profile. This sensory evaluation, combined with experience and knowledge, determines when a cheese is ready to be enjoyed.

Aging and ripening are not merely about preservation; they are about transformation. Through careful control of environment and time, cheesemakers unlock a world of flavors and textures, turning a simple ingredient into a culinary delight. Understanding this process allows us to appreciate the complexity of cheese and the skill involved in its creation. So, the next time you savor a perfectly aged cheddar or a creamy Camembert, remember the journey it took, from curd to masterpiece, in the cool, humid embrace of the aging room.

Dr. Nelson's Take: Is Some Cheese Okay for Your Diet?

You may want to see also

Mold and Bacteria: Introducing specific cultures to create unique flavors and characteristics

Cheese production is a delicate dance between science and art, where mold and bacteria play starring roles. These microscopic organisms are not merely bystanders but active participants, transforming milk into a diverse array of cheeses with distinct flavors, textures, and aromas. The introduction of specific cultures is a precise process, akin to casting characters in a play, each with a unique role to fulfill.

Consider the Penicillium camemberti, a mold culture responsible for the velvety white rind and creamy interior of Camembert. This mold is introduced at a specific stage, typically after the cheese has been formed and salted. The dosage is critical: too little, and the mold may not develop adequately; too much, and it can overpower the cheese's delicate flavor. A common practice is to spray a diluted solution of the mold spores onto the cheese's surface, allowing it to grow and ripen over 3-4 weeks. This process not only contributes to the cheese's characteristic bloomy rind but also breaks down the curd, creating a soft, spreadable texture.

In contrast, bacteria like Lactococcus lactis and Streptococcus thermophilus are often used in the production of cheddar and mozzarella. These bacteria are added to the milk in the form of a starter culture, typically at a dosage of 1-2% of the milk's weight. The bacteria's role is to acidify the milk, lowering its pH and causing the curd to set. This process is temperature-sensitive, with optimal growth occurring between 30-40°C (86-104°F). The specific strains and combinations of bacteria used can significantly impact the cheese's final flavor profile, with some strains contributing nutty or fruity notes, while others impart a more tangy or sharp taste.

The art of introducing mold and bacteria to cheese is not without its challenges. Cross-contamination is a significant concern, as unwanted microorganisms can spoil the cheese or produce off-flavors. To mitigate this risk, cheesemakers must maintain strict hygiene practices, including regular cleaning and sanitizing of equipment, as well as careful monitoring of temperature and humidity. Additionally, the use of phage-resistant bacterial strains has become increasingly important, as bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) can decimate a cheese's microbial ecosystem, leading to production losses.

A practical tip for home cheesemakers is to source high-quality cultures from reputable suppliers, ensuring they are stored and handled correctly. Cultures should be kept refrigerated and used within their recommended shelf life, typically 6-12 months. When introducing mold cultures, consider using a spray bottle to achieve an even distribution, and monitor the cheese's development closely, adjusting temperature and humidity as needed. For bacterial cultures, follow the supplier's recommended dosage and temperature guidelines, and be prepared to experiment with different strains to achieve your desired flavor profile. By mastering the introduction of specific mold and bacterial cultures, cheesemakers can unlock a world of unique and nuanced flavors, elevating their craft to new heights.

Vinegar Cheese Attack: The Shocking Story Behind the Unthinkable Toss

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese is not grown like a plant; it is made through a process of curdling milk, separating the curds from the whey, and then aging and shaping the curds into cheese.

Cheese is made primarily from milk (cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo), along with bacteria cultures, rennet (or a coagulant), and sometimes salt and additional flavorings.

Cheese is a manufactured product created through a controlled process of fermentation, curdling, and aging, rather than growing naturally on its own.