Cheese production is a fascinating journey that begins on dairy farms with cows and ends on the shelves of markets worldwide. The process starts with milking cows, typically twice a day, to collect fresh, high-quality milk. This milk is then transported to a dairy facility, where it undergoes pasteurization to eliminate harmful bacteria and ensure safety. Next, bacterial cultures and rennet are added to the milk to curdle it, separating it into solid curds and liquid whey. The curds are cut, stirred, and heated to release moisture, after which they are pressed into molds to form the desired shape. The cheese is then salted, either by brining or dry salting, to enhance flavor and preserve it. Following this, the cheese enters the aging or ripening stage, where it is stored in controlled environments for weeks, months, or even years, developing its unique texture and taste. Finally, the cheese is packaged and distributed to markets, where it is sold to consumers, completing the journey from cow to table.

Explore related products

$8.8 $15.99

What You'll Learn

- Milking and Collection: Cows are milked, and the milk is collected, cooled, and transported to cheese-making facilities

- Pasteurization and Culturing: Milk is pasteurized, then cultured with bacteria and rennet to curdle it

- Curdling and Cutting: Curds form, are cut into smaller pieces, and heated to release whey

- Pressing and Aging: Curds are pressed into molds, salted, and aged to develop flavor and texture

- Packaging and Distribution: Cheese is packaged, inspected, and distributed to retailers or markets for sale

Milking and Collection: Cows are milked, and the milk is collected, cooled, and transported to cheese-making facilities

The milking process begins before dawn on most dairy farms, where cows are herded into automated milking parlors designed to minimize stress and maximize efficiency. Each cow is milked using vacuum-assisted machines that simulate the natural suckling action of a calf, ensuring comfort and consistent yield. Modern systems include sensors to monitor milk flow and quality, automatically detaching when the udder is empty. This precision not only safeguards the cow’s health but also ensures the milk’s purity, a critical factor for cheese production.

Once extracted, the milk is immediately cooled to 4°C (39°F) within 30 minutes to inhibit bacterial growth and preserve its enzymatic properties. This rapid cooling is achieved through stainless steel bulk tanks equipped with refrigeration units, which also agitate the milk gently to prevent cream separation. Farms adhering to organic or artisanal standards may use smaller, batch-specific cooling systems to maintain unique flavor profiles. The cooled milk is then tested for fat content, protein levels, and somatic cell counts, with results often shared with cheese producers to tailor recipes accordingly.

Transportation from farm to facility is a logistical ballet, timed to ensure milk reaches its destination within 24–48 hours of milking. Insulated tankers maintain temperatures below 6°C (43°F) during transit, while GPS tracking and temperature sensors provide real-time data to prevent spoilage. For small-scale producers, this may involve daily pickups by local cheesemakers, while industrial operations rely on centralized hubs that consolidate milk from multiple farms. The journey is as much about preserving freshness as it is about meeting the volume demands of large-scale cheese production.

A critical yet often overlooked step is the filtration process, which removes debris and impurities before the milk leaves the farm. Microfilters with pore sizes as small as 5 microns capture dust, hair, and bacteria, ensuring the milk meets regulatory standards. This step is particularly vital for raw-milk cheeses, where the absence of pasteurization requires impeccable starting material. Properly filtered and cooled milk not only extends shelf life but also provides a clean canvas for the complex microbial transformations that define cheese character.

Finally, the milk’s arrival at the cheese-making facility marks the end of its journey as a raw ingredient and the beginning of its transformation into a culinary staple. Here, it is often standardized—adjusted for fat and protein content—to meet the specific requirements of the cheese variety being produced. This stage underscores the symbiotic relationship between farmer and cheesemaker, where meticulous milking and collection practices lay the foundation for the art and science of cheese creation. Without this careful handling, even the most skilled cheesemaker would struggle to craft a product of consistent quality.

Do Papa John's Cheese Sticks Include Bacon? Find Out Here!

You may want to see also

Pasteurization and Culturing: Milk is pasteurized, then cultured with bacteria and rennet to curdle it

Pasteurization is the cornerstone of modern cheese production, a critical step that ensures safety and consistency. Raw milk, straight from the cow, teems with microorganisms—some beneficial, others potentially harmful. Heating milk to a minimum of 72°C (161°F) for 15 seconds, or 63°C (145°F) for 30 minutes, destroys pathogens like *Salmonella* and *E. coli* while preserving the milk’s structural integrity. This process, named after Louis Pasteur, not only eliminates risks but also extends shelf life, making it a non-negotiable in commercial cheese-making. Without pasteurization, the variability of raw milk could lead to unpredictable curdling, off-flavors, or even health hazards.

Once pasteurized, the milk undergoes culturing, a transformative step that introduces specific bacteria to initiate fermentation. These bacteria, such as *Lactococcus lactis* or *Streptococcus thermophilus*, convert lactose into lactic acid, lowering the milk’s pH and preparing it for coagulation. The type and amount of bacteria added dictate the cheese’s flavor, texture, and acidity. For example, a dose of 1-2% bacterial culture by volume is typical for cheddar, while softer cheeses like Brie may require a higher concentration of *Penicillium* molds. Precision in this stage is key—too little culture results in weak curds, while too much can lead to excessive bitterness.

Rennet, an enzyme complex, is then added to complete the curdling process. Derived from the stomach lining of ruminants or produced through microbial fermentation, rennet coagulates milk proteins (casein) into a solid mass. A standard dosage is 0.02-0.05% of the milk’s weight, though this varies by cheese type and desired curd firmness. For instance, hard cheeses like Parmesan require a firmer curd, achieved with higher rennet concentrations. The curd’s formation is a delicate balance—too much rennet can make the cheese rubbery, while too little leaves it crumbly.

The interplay between pasteurization, culturing, and rennet addition is a masterclass in controlled chemistry. Pasteurization creates a clean slate, culturing introduces flavor and structure, and rennet seals the deal by forming curds. This trio of steps is not just technical but artistic, as small adjustments yield vastly different cheeses. For home cheese-makers, understanding these processes is essential. Always use a thermometer to monitor pasteurization temperatures, and source high-quality cultures and rennet for consistent results.

In the grand journey from cow to market, pasteurization and culturing are where science meets tradition. They bridge the raw material and the final product, ensuring safety, flavor, and texture. Without these steps, cheese would remain a gamble—but with them, it becomes a craft. Whether you’re a producer or a connoisseur, appreciating this phase deepens your understanding of why cheese is more than just milk—it’s a symphony of precision and patience.

Exploring the Global Cheese Varieties: A Comprehensive Count and Guide

You may want to see also

Curdling and Cutting: Curds form, are cut into smaller pieces, and heated to release whey

The transformation of milk into cheese begins with curdling, a process that separates the milk into solid curds and liquid whey. This is achieved by introducing a coagulant, typically rennet or microbial transglutaminase, which causes the milk proteins to bind together. For example, in traditional cheddar production, about 0.02% rennet (by weight of milk) is added, initiating curdling within 30–45 minutes at an optimal temperature of 30–32°C (86–90°F). This step is critical, as the curd’s texture and moisture content directly influence the final cheese’s consistency and flavor.

Once the curd forms, it is cut into smaller pieces using long-bladed knives or automated tools. The size of the cut determines the cheese’s moisture level: smaller pieces expel more whey, resulting in harder cheeses like Parmesan, while larger pieces retain moisture for softer varieties like mozzarella. For instance, cheddar curds are cut into 1.5–2 cm cubes, allowing whey to release gradually during the next stage. Cutting also increases the surface area, facilitating faster whey expulsion and preventing the curd from becoming too tough.

Heating the cut curds is the final step in this phase, a process known as "scalding." The curds are gently stirred and heated to temperatures ranging from 35°C (95°F) for soft cheeses to 45°C (113°F) for harder types. This drives off additional whey and firms the curds further. In cheddar production, scalding at 38–40°C (100–104°F) for 30–60 minutes is standard, ensuring the curds reach a "clean break" stage where they are supple yet resistant to breaking. Proper heating is crucial, as overheating can lead to rubbery curds, while underheating results in excess moisture and potential spoilage.

This curdling and cutting phase is a delicate balance of science and art. It requires precise control of temperature, time, and technique to achieve the desired curd characteristics. For home cheesemakers, investing in a thermometer accurate to ±1°C and practicing consistent cutting techniques can significantly improve results. Commercial producers often use computerized systems to monitor these variables, ensuring uniformity across batches. Mastery of this stage lays the foundation for the cheese’s texture, flavor, and shelf life, making it a cornerstone of the cheesemaking process.

Milk vs. Cheese: Understanding Their Role in Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE)

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.84 $29.99

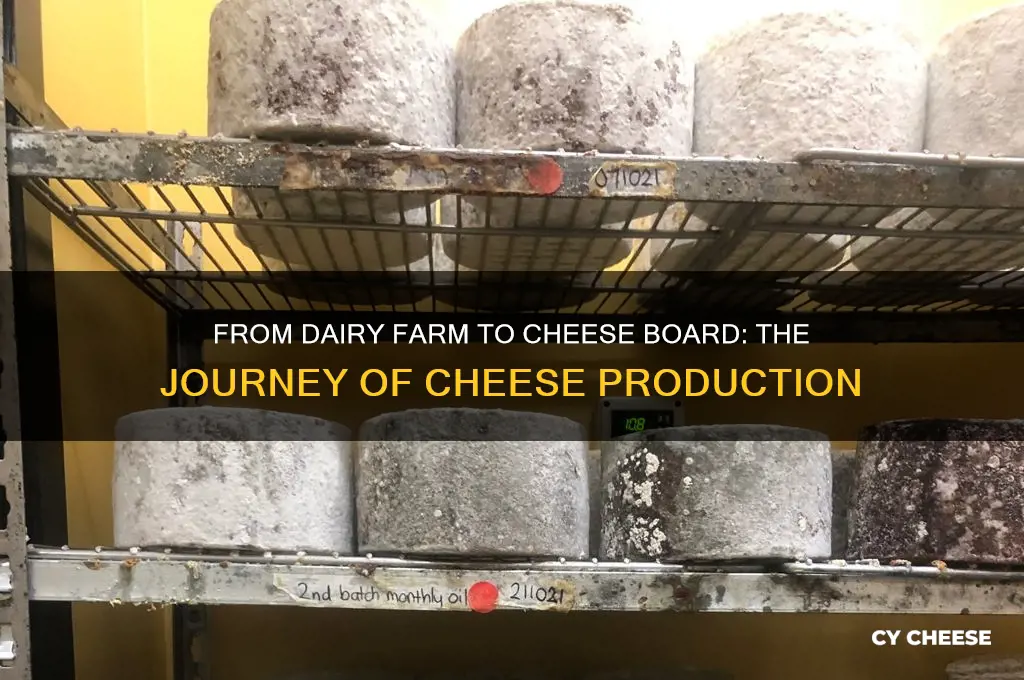

Pressing and Aging: Curds are pressed into molds, salted, and aged to develop flavor and texture

Once the curds have been separated from the whey, the real transformation begins. Pressing is a critical step that shapes the cheese’s final texture and moisture content. Curds are carefully transferred into molds, where they are subjected to controlled pressure. For softer cheeses like Brie, this might involve minimal pressing, allowing more moisture to remain. Harder cheeses, such as Cheddar, require heavier weights—often several hundred pounds—to expel excess whey and create a denser structure. The duration of pressing varies widely: fresh cheeses like ricotta may skip this step entirely, while aged cheeses can be pressed for hours or even days.

Salting follows pressing, and it’s more than just a flavor enhancer. Salt is applied directly to the curds or added to the brine in which the cheese is submerged. This step not only seasons the cheese but also slows bacterial growth, preserves the product, and influences moisture loss. For example, a 20% brine solution is commonly used for cheeses like Mozzarella, while dry-salted cheeses like Parmesan receive a precise 3-5% salt-to-curd ratio. Too little salt can lead to spoilage; too much can overpower the flavor. The timing and method of salting are as crucial as the quantity.

Aging is where cheese truly develops its character. During this stage, cheeses are stored in controlled environments—often cool, humid cellars or caves—for weeks, months, or even years. Temperature and humidity are meticulously regulated; for instance, Cheddar ages best at 50-55°F (10-13°C) with 85-90% humidity. As cheese ages, enzymes break down proteins and fats, creating complex flavors and textures. A young Gouda aged 1-6 months is mild and creamy, while a 2-year-old version becomes hard and sharp. Mold-ripened cheeses like Camembert rely on surface molds to develop their signature bloomy rind and creamy interior.

The interplay of pressing, salting, and aging is a delicate dance that cheesemakers master through experience. Each decision—how long to press, how much salt to use, or how long to age—impacts the final product. For home cheesemakers, experimenting with these variables can yield unique results. For instance, pressing curds for an extra hour can produce a firmer texture, while reducing salt slightly allows natural flavors to shine. Understanding these processes not only deepens appreciation for cheese but also empowers enthusiasts to craft their own artisanal creations.

In the market, the effects of pressing and aging are evident in the diversity of cheeses available. From the crumbly texture of feta to the crystalline crunch of aged Parmesan, these steps are the unsung heroes of cheesemaking. Consumers can decode labels to appreciate the craftsmanship behind each wheel or block. A cheese aged "12 months" or labeled "cave-aged" tells a story of patience and precision. By recognizing the role of pressing and aging, one gains a deeper connection to the art and science of transforming humble curds into a culinary masterpiece.

Does Cotija Cheese Melt Well on Tortilla Chips? A Tasty Experiment

You may want to see also

Packaging and Distribution: Cheese is packaged, inspected, and distributed to retailers or markets for sale

Once cheese has matured to its desired flavor and texture, the final steps in its journey from cow to market involve packaging, inspection, and distribution—a critical phase that ensures quality, safety, and appeal to consumers. Packaging serves multiple purposes: it protects the cheese from contamination, preserves freshness, and provides essential information such as type, weight, and expiration date. Modern packaging materials range from wax coatings for hard cheeses to vacuum-sealed plastic for softer varieties, each chosen to suit the cheese’s specific needs. For instance, cheddar might be wrapped in moisture-resistant film to prevent mold, while brie could be placed in breathable paper to maintain its rind’s integrity.

Inspection is a non-negotiable step in this process, governed by strict food safety regulations. Cheeses are checked for consistency in weight, appearance, and labeling accuracy. Advanced technologies like metal detectors and X-ray machines ensure no foreign objects are present, while microbial testing confirms the absence of harmful bacteria. For example, a batch of mozzarella destined for pizza production might undergo additional tests to verify its meltability and moisture content. These inspections not only safeguard consumer health but also protect the brand’s reputation.

Distribution is where logistics take center stage, requiring careful coordination to maintain the cheese’s quality during transit. Temperature-controlled trucks and containers are essential, especially for soft or semi-soft cheeses that spoil quickly if exposed to heat. A block of Parmesan, for instance, can tolerate a wider temperature range compared to a delicate Camembert, which must remain between 2°C and 4°C. Retailers often receive cheese in bulk, repackaging it into smaller portions for sale, while specialty markets might display artisanal cheeses in their original packaging to highlight craftsmanship.

The journey from packaging to shelf also involves strategic marketing. Labels often feature certifications like "organic" or "grass-fed," appealing to health-conscious consumers. QR codes linking to the cheese’s origin story or pairing suggestions add value, turning a simple purchase into an experience. For example, a wheel of Gouda might include a label suggesting it be paired with a specific local wine, fostering cross-promotions and enhancing customer engagement.

In conclusion, packaging and distribution are not mere afterthoughts but integral steps that bridge the gap between production and consumption. They require precision, innovation, and adherence to standards, ensuring that every slice or wedge of cheese meets expectations. Whether it’s a mass-produced cheddar or a handcrafted blue cheese, these final stages determine how the product is perceived—and enjoyed—by the end consumer.

Does Cheese-Making Calcium Chloride Expire? Shelf Life Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process begins with milking cows, typically twice a day. The milk is then quickly cooled to prevent bacterial growth and transported to a cheese-making facility.

The main steps include pasteurization (heating to kill bacteria), adding starter cultures (bacteria to ferment lactose), coagulating the milk with rennet (to form curds), cutting and heating the curds, draining the whey, and pressing the curds into molds.

Cheese is aged in controlled environments with specific temperature and humidity levels. Aging allows flavors to develop, textures to change, and moisture to evaporate, resulting in the desired characteristics of the cheese.

Pasteurization heats the milk to destroy harmful bacteria and pathogens, ensuring the cheese is safe for consumption. However, some artisanal cheeses use raw milk for unique flavors, though they must meet strict safety standards.

After production, cheese is packaged, labeled, and often vacuum-sealed to preserve freshness. It is then distributed through supply chains, including warehouses, retailers, and supermarkets, where it is sold to consumers.

![Artisan Cheese Making at Home: Techniques & Recipes for Mastering World-Class Cheeses [A Cookbook]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81eH1+cYeZL._AC_UY218_.jpg)