Colby cheese, a popular American cheese known for its mild, nutty flavor and semi-hard texture, is crafted through a precise process that begins with pasteurized cow’s milk. The milk is first heated and then inoculated with lactic acid bacteria to lower its pH, creating an environment conducive to curdling. Next, rennet is added to coagulate the milk, forming a solid mass called the curd. The curd is then cut into small pieces, stirred, and gently heated to release whey, a liquid byproduct. After draining the whey, the curds are salted, pressed into molds, and allowed to age for several weeks to develop their characteristic flavor and texture. This traditional method ensures Colby cheese retains its creamy consistency and subtle sweetness, making it a versatile favorite for sandwiches, snacks, and cooking.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Milk Selection: Starts with high-quality cow’s milk, often pasteurized for safety and consistency

- Bacterial Culture: Lactic acid bacteria are added to ferment milk, creating acidity for curdling

- Rennet Addition: Rennet enzyme is introduced to coagulate milk, forming curds and whey

- Curd Cutting & Heating: Curds are cut into small pieces and heated to release moisture and firm up

- Pressing & Aging: Curds are pressed into molds, salted, and aged for flavor development, typically 6+ months

Milk Selection: Starts with high-quality cow’s milk, often pasteurized for safety and consistency

The foundation of exceptional Colby cheese lies in the milk itself. High-quality cow's milk is paramount, serving as the canvas upon which the cheese's flavor and texture are painted. This isn't your average grocery store gallon; we're talking about milk sourced from healthy, well-cared-for cows, where diet and living conditions directly impact the milk's richness and purity. Think of it as the difference between a generic paint and a premium artist's grade – the quality of the base material dictates the final masterpiece.

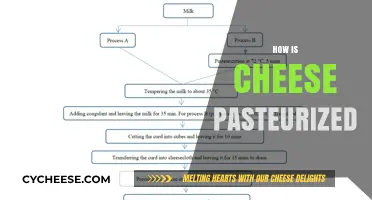

Milk selection for Colby cheese is a precise art. While raw milk can be used, pasteurization is common practice for safety and consistency. This process involves heating the milk to a specific temperature (typically around 161°F for 15 seconds) to eliminate harmful bacteria while preserving the milk's essential components. It's a delicate balance – too much heat can denature proteins and alter the milk's structure, affecting the cheese's final texture.

Discover the Ultimate NYC Deli Classic: The Chopped Cheese Sandwich

You may want to see also

Bacterial Culture: Lactic acid bacteria are added to ferment milk, creating acidity for curdling

The transformation of milk into Colby cheese begins with a microscopic army: lactic acid bacteria. These single-celled organisms, specifically strains like *Lactococcus lactis* and *Streptococcus thermophilus*, are the catalysts for the fermentation process that defines this cheese's character. Their role is both simple and profound: they consume lactose, the natural sugar in milk, and produce lactic acid as a byproduct. This acidification is the cornerstone of curdling, the first visible step in cheese making.

Without these bacteria, milk would remain a liquid, lacking the acidity needed for the proteins to coagulate. The specific strains used can influence the flavor profile of the final cheese, with some imparting a milder taste and others contributing to a tangier, more complex flavor.

Imagine a warm vat of milk, its surface still and serene. The addition of a carefully measured dose of lactic acid bacteria culture, typically around 1-2% of the milk volume, initiates a silent revolution. Over the course of several hours, these bacteria multiply, their metabolic activity steadily increasing the acidity of the milk. This process is highly temperature-sensitive, with an optimal range of 86-95°F (30-35°C) for most Colby cheese cultures. Too low, and the bacteria become sluggish; too high, and they may die off.

As the acidity rises, the milk's proteins begin to denature and coagulate, forming a soft, custard-like mass. This curd is the foundation upon which Colby cheese is built.

The choice of bacterial culture is not merely a technical detail; it's a crucial decision that shapes the cheese's identity. Different strains produce varying levels of lactic acid and other metabolites, influencing not only the curdling process but also the flavor, texture, and even the shelf life of the final product. For Colby, a semi-hard cheese with a mild, nutty flavor, specific cultures are selected to achieve the desired balance of acidity and sweetness.

Mastering the art of bacterial culture in cheese making requires precision and patience. It's a delicate dance, where temperature, time, and the specific characteristics of the chosen bacteria all play a role. But the reward is a cheese with a unique personality, a testament to the transformative power of these microscopic organisms.

The Surprising Journey of Cheese: Miles Traveled from Farm to Table

You may want to see also

Rennet Addition: Rennet enzyme is introduced to coagulate milk, forming curds and whey

The transformation of milk into cheese begins with a delicate dance of enzymes, and rennet plays the starring role. Derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals or produced through microbial fermentation, rennet contains chymosin, the enzyme responsible for coagulating milk. This process is not merely a chemical reaction; it’s a precise art that dictates the texture, flavor, and structure of the final cheese. For Colby cheese, rennet is added at a specific stage after the milk has been warmed and cultured, initiating the separation of curds and whey—a pivotal moment in cheesemaking.

Steps for Rennet Addition in Colby Cheese:

- Prepare the Milk: Heat pasteurized milk to 80–85°F (27–29°C) and add lactic acid bacteria cultures to acidify it. Allow 30–45 minutes for the cultures to activate, lowering the pH to around 6.4–6.6.

- Measure Rennet Dilution: Dilute liquid rennet (typically 1:10 with cool, non-chlorinated water) to ensure even distribution. For 10 gallons of milk, use 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon of rennet, depending on its strength.

- Add Rennet: Stir the milk gently in an up-and-down motion for 1–2 minutes to incorporate the rennet. Avoid vigorous stirring, as it can break the curd prematurely.

- Allow Coagulation: Let the milk rest undisturbed for 30–60 minutes until a clean break is achieved. Test by inserting a knife; if the curd separates cleanly, it’s ready.

Cautions and Troubleshooting:

Over-stirring or using too much rennet can result in a tough, rubbery curd, while under-stirring or insufficient rennet may prevent proper coagulation. If the milk fails to set, check the rennet’s potency or ensure the milk wasn’t ultra-pasteurized, as this can inhibit enzyme activity. Always use food-grade rennet and avoid chlorinated water, as chlorine can deactivate the enzyme.

Comparative Insight:

Rennet’s role in Colby cheese contrasts with its use in harder cheeses like Cheddar, where longer aging and higher acidity require more robust curd formation. In Colby, the goal is a milder, open texture, achieved through precise rennet dosage and shorter aging. Vegetarian alternatives like microbial rennet can be used, though traditionalists argue animal rennet yields a superior flavor profile.

Practical Takeaway:

Mastering rennet addition is about timing, temperature, and technique. For home cheesemakers, investing in a reliable thermometer and practicing consistency in measurements will yield curds that are firm yet tender—ideal for Colby’s characteristic melt-in-your-mouth quality. This step, though brief, is the linchpin of the entire process, turning liquid milk into the foundation of a beloved cheese.

Does Cheese Cause Nightmares? Unraveling the Myth Behind Dairy Dreams

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Curd Cutting & Heating: Curds are cut into small pieces and heated to release moisture and firm up

The transformation of milk into Colby cheese begins with a delicate dance of curd cutting and heating, a process that demands precision and care. Imagine a vat of warm, coagulated milk, its curds suspended in whey like islands in a sea. The cheesemaker’s knife slices through this mixture, dividing the curds into small, uniform pieces. This isn’t arbitrary; the size of the cut determines the cheese’s final texture. For Colby, curds are typically cut into ½-inch cubes, a size that strikes a balance between moisture release and structural integrity.

Heating follows cutting, and here lies the art of moisture control. The curds are gently warmed to temperatures between 120°F and 130°F (49°C to 54°C), a range that encourages whey expulsion without hardening the curds excessively. This step is critical: too little heat, and the cheese remains soft and crumbly; too much, and it becomes rubbery. The curds shrink as whey drains, their texture firming from a soft, custard-like consistency to a pliable, slightly springy mass. This stage is where Colby’s signature openness—its small, irregular eyes—begins to take shape, a contrast to the denser, smoother Cheddar.

Consider the science behind this process. Heat disrupts the curd’s protein matrix, causing it to contract and expel whey. Simultaneously, enzymes continue to break down lactose, further concentrating the curd’s structure. The cheesemaker must monitor this transformation closely, stirring the curds to ensure even heating and moisture loss. This isn’t a set-it-and-forget-it step; it’s a hands-on, observational process where timing and temperature are everything.

Practical tips for the home cheesemaker: use a long-bladed knife or curd cutter to achieve consistent cube sizes, and invest in a reliable thermometer to monitor heat accurately. Stir the curds slowly and gently during heating to avoid breaking them into smaller pieces, which can lead to a grainy texture. Remember, the goal is to create a curd that’s firm but not brittle, moist but not wet—a balance that defines Colby’s unique character.

In the end, curd cutting and heating are more than just steps in cheesemaking; they’re the foundation of Colby’s texture and flavor. This phase separates the ordinary from the exceptional, turning a simple curd into a cheese that’s both versatile and distinctive. Master this, and you’re well on your way to crafting a Colby that stands out in both taste and texture.

Gastroparesis and Cheese: Can You Still Enjoy Dairy Delights?

You may want to see also

Pressing & Aging: Curds are pressed into molds, salted, and aged for flavor development, typically 6+ months

The transformation of Colby cheese from curds to a flavorful, semi-hard cheese hinges on the meticulous process of pressing and aging. After the curds are formed and heated, they are carefully pressed into molds to expel excess whey and create a cohesive mass. This step is crucial, as it determines the cheese’s final texture—too little pressure results in a crumbly structure, while too much can make it dense and rubbery. The ideal pressure for Colby cheese typically ranges between 20 to 30 pounds per square inch, applied gradually over 12 to 24 hours. This controlled process ensures the curds retain enough moisture to develop the cheese’s characteristic open, slightly elastic texture.

Salting is the next critical step, and it’s not just about flavor. Salt is applied directly to the curds or added to the brine in which the cheese is soaked after pressing. The recommended salt concentration is 2-3% of the cheese’s weight, ensuring proper preservation and flavor balance. Salt acts as a natural preservative, inhibiting bacterial growth while enhancing the cheese’s taste profile. However, timing is key—salting too early can hinder moisture expulsion, while salting too late can lead to uneven flavor distribution. Master cheesemakers often use a combination of dry salting and brine immersion to achieve the perfect balance.

Aging is where Colby cheese truly develops its signature mild, nutty flavor and smooth texture. The cheese is typically aged for a minimum of 6 months, though some artisanal varieties may extend this period to 12 months or more. During aging, the cheese is stored in temperature-controlled environments, ideally between 35°F and 40°F with 85-90% humidity. This slow maturation allows enzymes and bacteria to break down proteins and fats, creating complex flavors and a firmer texture. Regular flipping of the cheese wheels ensures even moisture distribution and prevents mold growth. The longer the aging, the sharper and more pronounced the flavor becomes, though Colby is traditionally prized for its milder, buttery notes.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers include investing in a cheese press with adjustable pressure settings and using food-grade molds lined with cheesecloth for easy removal. For aging, a wine fridge or a cool, humid basement works well, provided the temperature remains consistent. If you lack a humid environment, placing a bowl of water in the aging space can help maintain moisture levels. Patience is paramount—rushing the aging process will yield inferior results. For those new to cheesemaking, starting with smaller batches allows for experimentation with pressing times and salt levels without significant waste.

Comparatively, Colby’s pressing and aging process differs from cheeses like Cheddar, which undergoes a more intense cheddaring step and longer aging for sharper flavors. Colby’s milder profile and shorter aging period make it more accessible for beginners, yet it still demands precision. The takeaway is that pressing and aging are not just steps in the process—they are the alchemy that transforms simple curds into a beloved cheese. By understanding and controlling these variables, cheesemakers can craft Colby that strikes the perfect balance between texture and taste.

Discover American Cheeses That Rival Spain's Iconic Flavors and Texture

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Colby cheese originated in Colby, Wisconsin, in 1885, when cheesemaker Joseph Steinwand developed it as a variation of traditional cheddar.

Colby cheese is typically made from pasteurized cow’s milk, though raw milk can also be used in some artisanal productions.

Colby is made using a washed-curd process, which gives it a milder flavor and softer texture compared to cheddar, which undergoes a cheddaring process.

Colby cheese is usually aged for 2 to 3 months, though some varieties may be aged longer for a sharper flavor.

The orange color of Colby cheese comes from the addition of annatto, a natural food coloring derived from the seeds of the achiote tree.