Cheddar cheese is a natural cheese that is relatively hard and off-white (or orange if colourings such as annatto are added). It is made from cow's milk and is produced all over the world, with the name originating from the village of Cheddar in Somerset, South West England. The process of making cheddar cheese is called cheddaring, and it involves coagulating milk, cutting the curds, salting and turning them, moulding and pressing them, and finally, maturing the cheese. The specific steps and techniques used can vary depending on the region and the cheesemaker's preferences, resulting in different flavours, colours, and qualities of cheddar cheese.

How is commercial cheddar cheese made?

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Cheddar cheese |

| Colour | Off-white or orange |

| Texture | Relatively hard |

| Taste | Sometimes sharp |

| Source | Cow's milk |

| Milk type | Unpasteurised |

| Additives | Rennet, cultures, salt |

| Processing | Acidification, curdling, cutting, cheddaring, salting, moulding, pressing, wrapping, maturing |

| Time | 6 months to 2 years |

| Location | Australia, Argentina, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, South Africa, Sweden, Finland, the United Kingdom, the United States, Uruguay |

| Producers | Kraft, Cheddar Gorge Cheese Co. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The process of cheddaring

Firstly, the curd mat is cut into sections, and the pieces are repeatedly flipped. The curds are very soft and watery, so they are scooped to the side and allowed to dry. They are then heavily salted, which helps to remove more moisture. The curds are turned several times during this process to ensure even drying.

Once the curds are dry enough, they are packed into wheel-shaped moulds wrapped in cheesecloth and stacked on top of each other. The weight from the stacking helps to squeeze out any remaining water. The wheels are continuously flipped or 'cheddared' until most of the moisture is removed, resulting in a solid block of newly pressed cheese.

During the cheddaring process, the cheesemaker closely monitors the acidity and temperature of the curd, as these factors influence the final product's taste and texture. The optimal level of fat content in the whey is 0.3% or less. The curds are handled gently to prevent fat and protein loss, which is essential for the cheese to be considered cheddar.

Cheese Wax: What's the Secret Ingredient?

You may want to see also

Coagulation and curdling

The process of making commercial cheddar cheese involves several stages, and coagulation and curdling are crucial steps in this transformation. Firstly, coagulation is the process of causing milk proteins to solidify and form curds. This is achieved by adding a coagulant or "rennet", which changes the structure of the proteins in the milk. The amount of rennet added is important, and typically, 85 to 115 grams of rennet is used per 450 kilograms of milk. The type of rennet can vary, and while traditional animal rennet is common, vegetarian rennet is also used. The milk used is typically cow's milk, which is unpasteurised to preserve its naturally occurring bacteria, resulting in a more complex flavour.

After adding the rennet, the mixture must be stirred thoroughly to ensure even coagulation. The curds then need to set for around 10 to 15 minutes. The cheesemaker plays a vital role at this stage, as they must carefully judge when the curds have set sufficiently. A common test to determine this is by inserting a flat blade at a 45-degree angle into the curd and slowly raising it; if the curd breaks cleanly, it is ready for cutting.

The curds are then cut into small pieces, typically using stainless steel knives or handheld frames with blades. This cutting process releases whey, a byproduct of milk curdling, which needs to be drained. The curds are gently handled to prevent fat and protein loss, which could impact the final product. The curds are then cooked by adding hot water to the vat, and this process is carefully monitored to avoid overcooking. The cooking temperature is usually around 39°C, and the curds are constantly stirred during this step.

The final steps in the coagulation and curdling process involve scalding and stirring the curds before draining any remaining whey. The curds are then ready for the next stage of cheddaring, where they are cut into blocks, salted, and turned to facilitate further drying. This cheddaring process is critical to the development of the cheese's final taste and texture. Overall, the coagulation and curdling stages of cheddar cheese-making require precise techniques and careful monitoring to ensure the desired outcome.

Cheese and Casein: Recombinant Chymosin's Role

You may want to see also

Cutting and processing curds

After cutting, the curds are handled gently and allowed to set again for 10 to 15 minutes. The curd is then cooked by adding hot water to the jacket of the vat (up to 39 °C or 102 °F). Constant stirring is required during this step to avoid uneven cooking or overcooking, and the cooking process takes 20–60 minutes. The whey's pH will be around 6.1 to 6.4 by the end of the cooking process.

The whey is then removed from the vat by draining it out, and the curds are raked to the sides to allow the remaining whey to drain. The curds and whey are scalded and stirred before being drained. The cheesemaker must repeatedly test and feel the curd to ensure it reaches the desired consistency. This stage requires the expertise of an experienced cheesemaker, as no industrialised process can replicate their art.

The curds are then cut into sections and turned and stacked to allow them to cool, drain further, and 'knit' together. The cheesemaker closely monitors the acidity and temperature of the curd during this stage, which is crucial for the final taste and texture of the cheese. The curd is then milled into small chips and heavily salted. The salt helps to draw out more moisture, and the curds are turned several times to facilitate this process.

Cheese Origins: A Global Perspective

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Draining the whey

To drain the whey, the curds are first gently handled to prevent fat and protein loss, which could impact the quality of the final cheese. The curds are then allowed to set again for a short period, typically 10 to 15 minutes. During this time, the curds are kept at a constant temperature by adding hot water to the jacket of the vat, ensuring even cooking. The whey's pH will rise during this cooking process, reaching a range of 6.1 to 6.4.

The next step is to remove the whey from the curds. This is done by allowing the whey to drain out of the vat, often through a gate that prevents the curds from escaping. Most of the whey is drained in this manner. The curds are then raked to the sides of the vat, creating two piles, and the remaining whey is drained down the middle. This step ensures that most of the whey is removed, with minimal loss of curds.

After draining the whey, the curds are further processed through a series of cutting, turning, and stacking. This process, known as cheddaring, allows the curds to cool, drain further, and "knit" together, contributing to the final texture and taste of the cheese. The curds are then milled into small chips and salted, before being filled into cheese moulds for pressing. The pressing process helps to remove even more moisture, resulting in a solid block of newly pressed cheddar cheese.

The Making of Bandon Cheese: A Tasty Location

You may want to see also

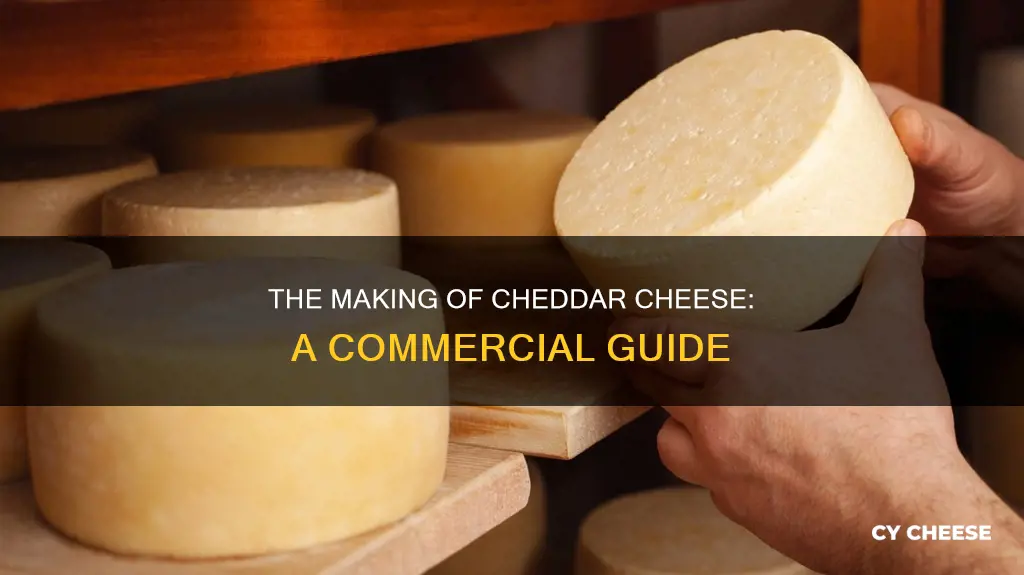

Pressing and moulding

Once the curds have been cut, stirred, cooked, and washed, they are ready for the cheddaring process. This is a critical stage in the development of the cheese, as it involves a series of cutting, turning, and stacking of the curds into blocks. The curds are cut into mats or sections, which are then repeatedly flipped. This allows the curds to cool, drain, and 'knit' together. The cheesemaker closely monitors the acidity and temperature of the curds at this stage, as this will contribute to the final taste and texture of the cheese.

After cheddaring, the curds are milled into small chips and heavily salted. The salt helps to draw out more moisture from the curds. The salted curds are then packed into moulds, which are wrapped in cheesecloth and stacked on top of each other. This stacking process helps to squeeze out even more water, as the weight of the blocks presses down on the curds. The wheels are continually flipped and turned until most of the moisture has been removed, resulting in a solid block of newly pressed cheese.

The moulds used for this process are typically wheel-shaped and made of traditional cotton or muslin cloth. The use of cheesecloth is a historical technique, as it allows the cheese to gradually dry and develop a rind. The cloth enables the cheese to breathe and interact with its atmosphere, allowing vital bacteria to develop. This bacteria is essential for the ageing process, as it helps to break down and rearrange the milk proteins, creating sharper flavours and a more developed taste.

The whole cheeses are then dressed in cloth before being transferred to maturing stores. The maturation period can vary, with younger 'mellow' cheddars aged for around six months, and older 'vintage' cheddars aged for up to two years or more. The environment in which the cheese is aged also plays a role in its final flavour and texture. For example, some cheddars are matured in natural caves, which impart unique characteristics to the cheese.

The Making of Limburger Cheese: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first step in making cheddar cheese is to prepare the milk. This involves sourcing milk from a local farm and monitoring its quality, composition, and temperature.

Cheddaring is a critical stage in the process of making cheddar cheese. It involves cutting, turning, and stacking the curds, allowing them to cool, drain, and "knit" together. This stage contributes significantly to the final taste and texture of the cheese.

The maturation period for cheddar cheese can vary. Younger cheddars are typically around six months old, while vintage cheddars can be up to two years old. Generally, the older the cheese, the stronger the flavour.