Fermentation is a cornerstone process in cheese production, playing a critical role in transforming milk into the diverse array of cheeses we enjoy today. By introducing specific bacteria and sometimes molds, fermentation initiates a series of biochemical reactions that break down lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, lowering the pH and coagulating milk proteins. This not only preserves the milk but also develops the characteristic flavors, textures, and aromas unique to each cheese variety. Additionally, fermentation contributes to the ripening process, allowing enzymes and microorganisms to further transform the cheese, enhancing its complexity and depth. Without fermentation, cheese would lack its distinctive qualities, making it an indispensable step in the art and science of cheesemaking.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Lactic Acid Production | Fermentation by lactic acid bacteria (LAB) converts lactose into lactic acid, lowering pH and coagulating milk proteins (casein), essential for curd formation. |

| Flavor Development | Fermentation produces enzymes and metabolites (e.g., diacetyl, acetaldehyde) that contribute to cheese flavor profiles, such as tangy, nutty, or earthy notes. |

| Texture Formation | Acidification and proteolysis during fermentation influence cheese texture by breaking down proteins and contributing to moisture loss, determining firmness or creaminess. |

| Preservation | Fermentation creates an acidic environment that inhibits spoilage bacteria and pathogens, extending cheese shelf life. |

| Ripening and Maturation | Secondary fermentation by bacteria and molds (e.g., Penicillium) during aging develops complex flavors, aromas, and textures in cheeses like Brie or Cheddar. |

| Nutrient Transformation | Fermentation breaks down lactose and proteins into more digestible forms, making cheese suitable for lactose-intolerant individuals. |

| Color Development | Certain bacteria and molds produce pigments (e.g., annatto, carotenoids) during fermentation, contributing to cheese color. |

| Gas Formation | In some cheeses (e.g., Swiss), fermentation by propionic acid bacteria produces carbon dioxide, creating characteristic eye formation. |

| Microbial Control | Competitive fermentation by LAB suppresses unwanted microorganisms, ensuring cheese safety and quality. |

| Aroma Compounds | Fermentation generates volatile compounds (e.g., esters, alcohols) that enhance the aromatic profile of cheese. |

Explore related products

$25.17 $39.95

What You'll Learn

- Microbial Action: Fermentation relies on bacteria and fungi to transform milk sugars into lactic acid

- Curd Formation: Lactic acid coagulates milk proteins, creating the solid curds essential for cheese

- Flavor Development: Fermentation enzymes break down proteins and fats, producing unique cheese flavors

- Texture Control: Microbial activity influences moisture loss and structure, determining cheese texture

- Preservation: Fermentation lowers pH, inhibiting spoilage microbes and extending cheese shelf life

Microbial Action: Fermentation relies on bacteria and fungi to transform milk sugars into lactic acid

Fermentation is the silent maestro in the orchestra of cheese making, and its microbial action is the key to unlocking the transformation of milk into cheese. At the heart of this process are bacteria and fungi, microscopic powerhouses that convert milk sugars, primarily lactose, into lactic acid. This conversion is not just a chemical reaction; it’s a metabolic symphony that acidifies the milk, curdles it, and sets the stage for the complex flavors and textures we associate with cheese. Without these microbes, milk would remain just that—milk—lacking the structure and character that define cheese.

Consider the role of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), such as *Lactococcus lactis* and *Streptococcus thermophilus*, which are commonly used in cheese production. These bacteria consume lactose and produce lactic acid, lowering the pH of the milk. This acidification is critical for several reasons. First, it coagulates milk proteins, causing them to separate into curds and whey. Second, it creates an environment hostile to harmful pathogens, ensuring the safety of the cheese. For example, in the production of cheddar, LAB reduce the pH to around 5.2–5.4, a level that not only firms the curd but also inhibits the growth of spoilage organisms. The dosage and type of bacteria used can vary depending on the cheese variety, with some recipes requiring specific strains to achieve desired flavors and textures.

Fungi, particularly molds, play a complementary role in certain cheeses, adding complexity through their enzymatic activity. In blue cheeses like Roquefort or Gorgonzola, *Penicillium roqueforti* spores are introduced to break down fats and proteins, creating the distinctive veins and pungent aroma. Unlike bacteria, which primarily focus on lactose fermentation, fungi contribute by producing lipases and proteases that degrade milk components into smaller molecules, enhancing flavor profiles. This dual microbial action—bacteria for acidification and fungi for enzymatic breakdown—illustrates the layered sophistication of fermentation in cheese making.

Practical considerations for harnessing microbial action include temperature and time. LAB thrive in mesophilic (20–40°C) or thermophilic (40–45°C) conditions, depending on the cheese type. For instance, mozzarella uses thermophilic bacteria to achieve a quick, firm curd, while brie relies on mesophilic cultures for a softer texture. Home cheese makers should monitor these parameters closely, as deviations can lead to off-flavors or incomplete curdling. Additionally, using starter cultures with precise bacterial counts (typically 1–2% of milk volume) ensures consistent results. For fungi-driven cheeses, proper aeration is crucial to allow mold growth, often achieved by piercing the cheese during aging.

The takeaway is clear: microbial action in fermentation is not just critical—it’s the cornerstone of cheese formation. By understanding the roles of bacteria and fungi, cheese makers can manipulate milk sugars into lactic acid and beyond, crafting products that range from mild and creamy to bold and complex. Whether you’re a professional or a hobbyist, mastering this microbial dance opens the door to endless possibilities in the art of cheese making.

Perfect Cheese-Making Temperature: How Hot Should Milk Be?

You may want to see also

Curd Formation: Lactic acid coagulates milk proteins, creating the solid curds essential for cheese

Lactic acid, a byproduct of fermentation, acts as the invisible sculptor of cheese, transforming liquid milk into the solid foundation of curds. This process begins when lactic acid bacteria (LAB), such as *Lactococcus lactis*, metabolize lactose in milk, producing lactic acid as a waste product. As lactic acid accumulates, it lowers the milk’s pH, causing the negatively charged casein proteins to lose their repulsion and bind together. This coagulation forms a network of solid curds suspended in whey, the first tangible step in cheese production. Without this acidification, milk proteins would remain dispersed, and cheese as we know it could not form.

Consider the precision required in this step: the pH must drop to around 4.6 for most cheeses, a level at which casein proteins precipitate optimally. Too little lactic acid, and the curds remain weak; too much, and they become brittle. Artisan cheesemakers often monitor pH levels using meters or test strips, adjusting conditions to ensure the curds achieve the desired texture. For example, in mozzarella production, a slower fermentation yields softer, more elastic curds, while harder cheeses like cheddar require a sharper drop in pH for firmer curds. This delicate balance underscores the critical role of lactic acid in curd formation.

The science behind curd formation is both elegant and practical. Lactic acid not only coagulates proteins but also inhibits spoilage bacteria, extending the shelf life of the cheese. This dual function highlights why fermentation is indispensable in cheesemaking. Home cheesemakers can replicate this process by adding a starter culture containing LAB to pasteurized milk, maintaining a temperature of 86–100°F (30–38°C) to encourage bacterial activity. After 12–48 hours, depending on the cheese type, the curds will be ready for cutting and draining, marking the transition from liquid milk to solid cheese.

Comparing traditional and industrial methods reveals the adaptability of curd formation via fermentation. While artisanal cheesemakers rely on natural LAB present in raw milk or added cultures, industrial producers often use direct acidification with diluted hydrochloric or acetic acid for faster results. However, this shortcut bypasses the flavor development achieved through fermentation, underscoring why purists insist on the traditional approach. The choice of method ultimately depends on the desired cheese characteristics, but both hinge on the principle of acid-induced coagulation.

In essence, curd formation is the alchemy of cheese, where lactic acid transforms milk into a solid matrix, setting the stage for aging, flavor development, and texture refinement. Whether crafting a creamy brie or a sharp cheddar, understanding this process empowers cheesemakers to control outcomes with precision. By harnessing the power of fermentation, even beginners can create cheeses that rival those of seasoned artisans, proving that curd formation is not just a step—it’s the cornerstone of cheesemaking.

Reselling Cheese in NY: Permit Requirements Explained for Entrepreneurs

You may want to see also

Flavor Development: Fermentation enzymes break down proteins and fats, producing unique cheese flavors

Fermentation is the unsung hero of cheese flavor, a biochemical symphony where enzymes conduct the breakdown of proteins and fats into a chorus of taste and aroma. This process, driven by microorganisms like lactic acid bacteria and molds, transforms bland curds into complex, nuanced cheeses. For instance, in cheddar, starter cultures produce lactic acid, which activates enzymes to break down milk proteins into peptides and amino acids. These compounds contribute to the cheese’s sharp, tangy profile. Similarly, in blue cheeses like Roquefort, Penicillium molds release lipases that cleave fats into fatty acids, creating their distinctive pungent, buttery notes. Without fermentation, cheese would lack the depth and character that make it a culinary cornerstone.

To harness fermentation for flavor development, cheesemakers must control time, temperature, and microbial activity. For example, aging a semi-hard cheese like Gruyère at 50–55°F (10–13°C) for 5–12 months allows enzymes to slowly hydrolyze proteins and fats, yielding nutty, caramelized flavors. In contrast, fresh cheeses like mozzarella undergo minimal fermentation, preserving mild, milky notes. Practical tip: Home cheesemakers can experiment with extending aging times in a humidity-controlled environment (85–90%) to intensify flavors, but monitor for over-fermentation, which can lead to bitterness or ammonia-like off-flavors.

The role of enzymes in fermentation is both precise and unpredictable, akin to a chef seasoning a dish. For instance, proteases break down casein proteins into smaller peptides, contributing umami and savory qualities, while lipases target milk fats, releasing esters and aldehydes that add fruity or floral undertones. In washed-rind cheeses like Époisses, bacteria produce enzymes that degrade surface proteins, creating a sticky rind and robust, earthy flavors. Caution: Overuse of lipase-producing cultures can make cheese unpalatably sharp, so follow dosage guidelines—typically 0.05–0.1% of milk weight for lipase preparations.

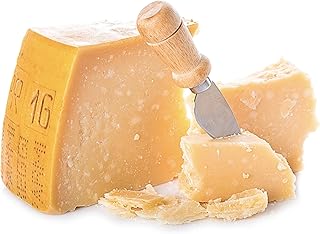

Comparing fermented and non-fermented dairy highlights fermentation’s indispensability. Cottage cheese, a minimally fermented product, retains a simple, fresh profile, whereas aged Parmigiano-Reggiano, fermented and aged for 24 months, boasts a crystalline texture and complex flavors of broth, fruit, and spice. This contrast underscores how fermentation enzymes act as flavor architects, sculpting cheese identity. Takeaway: Whether crafting a mild chèvre or a bold Gouda, understanding and manipulating fermentation is key to unlocking a cheese’s flavor potential.

Chilling Cheese: Finding the Perfect Cold Temperature for Smoking

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$18.69 $29.95

Texture Control: Microbial activity influences moisture loss and structure, determining cheese texture

The texture of cheese, from the creamy smoothness of Brie to the crumbly bite of feta, is a direct result of microbial activity during fermentation. Lactic acid bacteria, the primary fermentative agents, produce acids that lower the pH of the milk, causing proteins to coagulate and form a gel-like structure. This initial step is crucial, but it’s the subsequent microbial actions—such as enzyme production and moisture management—that refine the texture. For instance, in semi-hard cheeses like cheddar, bacteria like *Lactococcus lactis* metabolize lactose into lactic acid, which tightens the protein matrix, expelling whey and creating a denser, firmer texture. Without this microbial intervention, cheese would lack the structural integrity that defines its mouthfeel.

Consider the role of moisture loss in texture development. In hard cheeses like Parmesan, bacteria and molds work in tandem to expel whey through a process called syneresis. This is accelerated by cutting and pressing the curd, but microbial activity ensures the process is thorough. For example, in Gruyère, propionic acid bacteria produce carbon dioxide gas, creating the cheese’s signature eyes while further drying the matrix. Conversely, in soft cheeses like Camembert, molds like *Penicillium camemberti* grow on the surface, breaking down proteins and fats but retaining moisture, resulting in a velvety interior. Controlling moisture loss through microbial selection and aging time is thus a precise science, dictating whether a cheese will be spreadable or sliceable.

Practical tips for texture control in cheesemaking hinge on understanding microbial behavior. For a firmer texture, extend the fermentation time to allow more acid production and whey expulsion. For example, aging cheddar for 6–12 months at 50–55°F enhances its crumbly texture as bacteria continue to break down proteins. Conversely, halting fermentation early, as in fresh cheeses like mozzarella, preserves moisture and softness. Adding specific molds, such as *Geotrichum candidum* in Saint-Marcellin, encourages a thin, bloomy rind while maintaining a creamy interior. Monitoring pH levels—aiming for 4.6–5.0 for semi-hard cheeses—is critical, as deviations can lead to uneven texture.

Comparing microbial strategies across cheese types highlights their versatility. In blue cheeses like Roquefort, *Penicillium roqueforti* penetrates the curd, releasing proteases and lipases that break down proteins and fats, creating a creamy yet crumbly texture with veins of pungent flavor. In contrast, washed-rind cheeses like Époisses rely on bacteria like *Brevibacterium linens* to create a sticky, orange rind while retaining a gooey interior. These contrasting approaches demonstrate how microbial selection and management can achieve radically different textures within the same broad category of cheese.

The takeaway is clear: microbial activity is the architect of cheese texture, manipulating moisture and structure through precise biochemical processes. By selecting specific bacteria and molds, controlling fermentation conditions, and adjusting aging times, cheesemakers can engineer textures ranging from buttery to brittle. Understanding these mechanisms not only deepens appreciation for the craft but also empowers experimentation. Whether crafting a home-made gouda or perfecting a brie, mastering microbial texture control transforms cheese from a simple food into a nuanced art form.

Discover the Size of Domino's Philly Cheese Steak Sandwich

You may want to see also

Preservation: Fermentation lowers pH, inhibiting spoilage microbes and extending cheese shelf life

Fermentation is the unsung hero of cheese preservation, a process that transforms milk into a durable, flavorful food. At its core, fermentation lowers the pH of the cheese matrix, creating an environment hostile to spoilage microbes. Lactic acid bacteria, such as *Lactococcus lactis*, convert lactose into lactic acid, reducing the pH from around 6.6 in fresh milk to as low as 5.0 in aged cheeses. This acidic shift acts as a natural preservative, inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria like *Listeria* and *E. coli*, which struggle to survive below pH 5.5. Without fermentation, cheese would spoil rapidly, rendering it unsafe for consumption.

Consider the practical implications of this pH drop. For instance, in the production of cheddar, the curd is heated and pressed, but it’s the fermentation-driven acidification that ensures long-term stability. A pH below 5.3 is critical to prevent late blowing, a defect caused by gas-producing *Clostridium* spores. Similarly, in soft cheeses like Camembert, fermentation not only develops flavor but also suppresses unwanted mold growth, extending shelf life from days to weeks. Home cheesemakers can replicate this by monitoring pH levels during fermentation, aiming for a target range of 5.0–5.3 for most aged cheeses.

The preservation benefits of fermentation extend beyond microbial inhibition. Lower pH also slows enzymatic activity, reducing protein and fat degradation that leads to off-flavors and texture defects. For example, in blue cheeses like Roquefort, fermentation-induced acidity balances the action of *Penicillium roqueforti*, preventing over-ripening while allowing desirable mold development. This dual action—microbial control and enzymatic regulation—is why fermented cheeses like Parmesan can age for over a year without spoiling, whereas fresh, unfermented cheeses like ricotta last only a few days.

To harness fermentation’s preservative power, cheesemakers must control temperature and time meticulously. Optimal fermentation temperatures (20–30°C) encourage lactic acid production without overheating the curd. For hard cheeses, extending fermentation by 12–24 hours further lowers pH, enhancing preservation. However, caution is necessary: over-acidification can lead to bitter flavors or curd breakdown. Regular pH testing with a meter or strips is essential, especially for beginners. By mastering this balance, cheesemakers can create products that not only last longer but also develop complex flavors over time.

In essence, fermentation’s role in lowering pH is a cornerstone of cheese preservation, blending science and craft to transform perishable milk into a stable, enduring food. Whether in a commercial dairy or a home kitchen, understanding and controlling this process is key to producing cheese that is both safe and delicious. Without fermentation’s acidic shield, the rich diversity of cheeses we enjoy today would simply not exist.

The Ultimate Guide to Naming Your Meat and Cheese Board

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fermentation is critical in cheese production as it converts lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, lowering the pH and coagulating milk proteins. This process creates the structure, texture, and flavor profile of cheese.

Fermentation bacteria produce enzymes and metabolites during the process, which break down milk components into compounds like diacetyl, acetaldehyde, and esters. These compounds are responsible for the distinctive flavors and aromas of different cheeses.

Controlling fermentation time ensures the desired acidity level, texture, and flavor development. Too little fermentation can result in a bland, unformed cheese, while too much can make it overly sour or crumbly.

No, cheese cannot be made without fermentation. Fermentation is essential for curdling milk, preserving it, and developing the characteristic taste and texture of cheese. Without it, the milk would simply spoil.

![The Cheese Board: Collective Works: Bread, Pastry, Cheese, Pizza [A Baking Book]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81FLQklK42L._AC_UY218_.jpg)