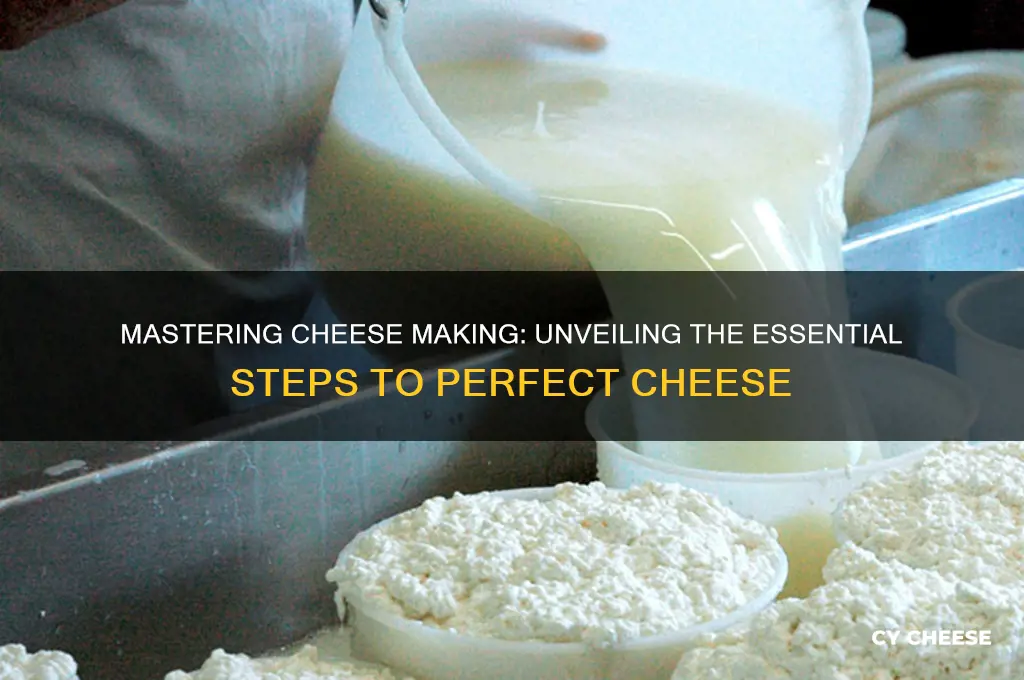

Cheese making is a fascinating and intricate process that transforms milk into a diverse array of flavors, textures, and aromas. While the specific steps can vary depending on the type of cheese being produced, the general process typically involves several key stages. These include milk preparation, where the milk is often pasteurized or left raw, followed by coagulation, where rennet or acid is added to curdle the milk. Next, the cutting and stirring of the curd helps release whey, and then the curds are heated and drained to further remove moisture. The curds are then pressed and molded into the desired shape, after which the cheese undergoes salting, either by brining or dry salting. Finally, the cheese is aged or ripened, during which time bacteria and molds develop its unique characteristics. Understanding these steps not only highlights the complexity of cheese making but also deepens appreciation for this ancient craft.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of Steps | Typically 8-10, but can vary depending on cheese type |

| Basic Steps | 1. Milk Preparation 2. Acidification 3. Coagulation 4. Cutting the Curd 5. Cooking the Curd 6. Draining and Pressing 7. Salting 8. Ripening/Aging |

| Additional Steps (for specific cheeses) | - Molding - Brining - Smoking - Washing |

| Timeframe | Can range from a few hours (fresh cheeses) to several years (aged cheeses) |

| Key Factors Affecting Steps | Cheese type, milk type, desired texture, flavor profile |

| Common Variations | - Direct acidification (e.g., paneer) - Secondary cultures (e.g., blue cheese) - Mechanical stretching (e.g., mozzarella) |

| Equipment Needed | Rennet, thermometers, cheese presses, molds, aging environments |

| Skill Level Required | Varies; basic cheese making is accessible, but advanced techniques require experience |

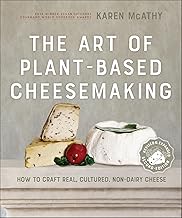

Explore related products

$8.8 $15.99

What You'll Learn

- Milk Selection: Choosing raw or pasteurized milk based on desired cheese type and flavor

- Coagulation Process: Adding rennet or acid to curdle milk, separating curds from whey

- Curd Handling: Cutting, stirring, and heating curds to release moisture and develop texture

- Salting and Pressing: Adding salt and applying pressure to shape and preserve the cheese

- Aging and Ripening: Storing cheese in controlled conditions to develop flavor and texture

Milk Selection: Choosing raw or pasteurized milk based on desired cheese type and flavor

The foundation of any cheese lies in its milk, and the choice between raw and pasteurized milk is a pivotal decision that shapes the final product's character. Raw milk, teeming with native bacteria and enzymes, offers a complex flavor profile and a unique terroir-driven essence. However, it demands meticulous handling and adherence to strict hygiene protocols to mitigate potential health risks. Pasteurized milk, on the other hand, provides a safer, more predictable base, but often at the cost of nuanced flavors and the need for added bacterial cultures to initiate fermentation.

For artisanal cheesemakers aiming to craft traditional, robustly flavored cheeses like Gruyère or Cheddar, raw milk is often the preferred choice. Its inherent microbial diversity contributes to the development of deep, earthy notes and a distinctive texture. However, regulatory constraints in many regions mandate that raw milk cheeses be aged for a minimum of 60 days at 35°F (2°C) to ensure safety, which can extend production timelines and increase costs. Pasteurized milk, while lacking raw milk’s complexity, is ideal for fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta, where mildness and consistency are prized.

When selecting milk, consider the desired cheese type and its flavor profile. For aged, hard cheeses, raw milk’s natural enzymes accelerate aging and enhance flavor depth. For soft, surface-ripened cheeses like Brie, pasteurized milk paired with specific bacterial cultures can achieve a creamy interior and bloomy rind without the variability of raw milk. Always source milk from reputable suppliers, ensuring it meets quality standards for fat content (typically 3.5–4.0% for cow’s milk) and is free from antibiotics or additives that could hinder coagulation.

Practical tips for milk selection include testing raw milk for acidity (aim for a pH of 6.6–6.8) before use and warming pasteurized milk to 86°F (30°C) to optimize bacterial activity. If using pasteurized milk for aged cheeses, add a mesophilic starter culture at a rate of 1–2% of milk volume to reintroduce essential bacteria. Ultimately, the choice between raw and pasteurized milk hinges on balancing flavor aspirations, safety considerations, and regulatory compliance, each decision steering the cheese toward its intended identity.

How Many Grams in a Tablespoon of Cheese?

You may want to see also

Coagulation Process: Adding rennet or acid to curdle milk, separating curds from whey

The coagulation process is a pivotal moment in cheese making, transforming liquid milk into a solid foundation for cheese. This step involves adding a coagulant—either rennet or acid—to milk, causing it to curdle and separate into curds (the solid part) and whey (the liquid part). The choice of coagulant and its dosage significantly influence the texture, flavor, and overall character of the final cheese. For instance, rennet, derived from animal enzymes, is commonly used for hard cheeses like cheddar, while acids such as lemon juice or vinegar are typical for softer, fresher cheeses like ricotta.

Steps to Master Coagulation:

- Prepare the Milk: Heat the milk to the optimal temperature for the chosen coagulant. For rennet, this is typically 30–35°C (86–95°F), while acid coagulation often works best at room temperature or slightly warmer.

- Add the Coagulant: For rennet, dilute 1–2 drops of liquid rennet in 1/4 cup of cool, non-chlorinated water per gallon of milk. Stir gently for 1–2 minutes. Acid coagulation requires adding 2–4 tablespoons of lemon juice or vinegar per gallon of milk, stirring until the milk curdles.

- Allow to Set: Cover the milk and let it rest undisturbed for 10–60 minutes, depending on the coagulant. Rennet-coagulated milk takes longer to set compared to acid-coagulated milk.

- Separate Curds and Whey: Once the curd forms, gently cut it into uniform cubes using a long knife or curd cutter. Slowly stir the curds to release more whey, then ladle or strain them into a mold or cheesecloth-lined container.

Cautions and Tips:

Over-stirring or excessive heat can toughen the curds, so handle them delicately. For rennet, ensure the milk is not too acidic, as this can hinder its effectiveness. If using acid, avoid over-coagulating, as it can result in a grainy texture. Always use food-grade coagulants and sanitized equipment to prevent contamination.

Comparative Insight:

Rennet coagulation produces a cleaner break between curds and whey, ideal for aged cheeses, while acid coagulation yields a softer, more fragile curd suited for fresh cheeses. Understanding these differences allows cheese makers to tailor the process to their desired outcome.

Practical Takeaway:

Mastering the coagulation process requires precision and patience. Experiment with different coagulants and dosages to achieve the desired texture and flavor. Whether crafting a sharp cheddar or creamy ricotta, this step lays the groundwork for cheese-making success.

How to Easily Connect to Chuck E. Cheese's Free WiFi Network

You may want to see also

Curd Handling: Cutting, stirring, and heating curds to release moisture and develop texture

Curd handling is a delicate dance of precision and patience, where the transformation from milky curds to textured cheese begins. After coagulation, the curd is a soft, gelatinous mass, but it’s far from the final product. Cutting the curd into uniform pieces exposes more surface area, allowing whey to drain and enzymes to work evenly. This step is critical: too large, and moisture retention leads to a crumbly texture; too small, and the curd may toughen. For example, in cheddar making, the curd is cut into 1-inch cubes, while mozzarella curd is cut finer to encourage elasticity. The goal is to create a consistent structure that will dictate the cheese’s final mouthfeel.

Stirring the curd is both an art and a science, requiring careful attention to temperature and timing. As the curd is gently agitated, whey is expelled, and the curd particles knit together, forming a firmer mass. This stage is where the cheese’s texture begins to develop—a slow stir promotes a smoother texture, while vigorous stirring can create a denser, chewier result. In Swiss cheese production, stirring is minimal to preserve large eyes, while Parmesan curd is stirred vigorously to expel as much whey as possible. The temperature during stirring is equally crucial; for most cheeses, maintaining a range of 90–100°F (32–38°C) ensures the curd firms without becoming rubbery.

Heating the curd is the final act in curd handling, driving off excess moisture and further developing texture. This step must be executed with care, as overheating can cause the curd to shrink or become grainy. For semi-hard cheeses like Gouda, the curd is heated to around 110°F (43°C), while harder cheeses like Gruyère may reach 120°F (49°C). The curd’s acidity plays a role here—higher acidity can cause the curd to toughen more quickly, so pH levels must be monitored. A practical tip: use a thermometer and stir constantly during heating to ensure even distribution of heat and prevent scorching.

The interplay of cutting, stirring, and heating is what transforms a simple curd into a complex cheese. Each action builds on the last, creating a foundation for aging and flavor development. For instance, a well-handled curd in cheddar will have a slightly springy texture, ready to absorb the tang of aging, while a poorly handled curd may result in a dry, crumbly cheese. The key takeaway is control—control over size, movement, and temperature. Master these, and the curd will yield its moisture willingly, revealing the texture that defines the cheese’s character.

Smart Points in Polly-O Original Ricotta Cheese: A Nutritional Breakdown

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Salting and Pressing: Adding salt and applying pressure to shape and preserve the cheese

Salt plays a dual role in cheesemaking: preservation and flavor enhancement. Its antimicrobial properties inhibit unwanted bacterial growth, extending the cheese's shelf life. Simultaneously, salt draws moisture from the curds, concentrating flavors and creating a firmer texture. This delicate balance is crucial; too little salt risks spoilage, while excess can overpower the cheese's natural character.

Salting techniques vary depending on the cheese style. For hard cheeses like cheddar, curds are typically cut into small pieces, allowing salt to penetrate evenly. A common guideline is 1.5-2% salt by weight of the curds. This can be added directly to the curds or dissolved in a brine solution for immersion. Softer cheeses, like mozzarella, often receive a lighter salting, around 0.5-1%, applied directly to the surface or through a brine bath.

Pressing is the sculptor's chisel of cheesemaking, shaping the curds into their final form. The pressure applied consolidates the curds, expelling excess whey and creating a denser structure. The intensity and duration of pressing dictate the cheese's texture, from crumbly feta to semi-soft Brie. For example, cheddar curds are pressed under heavy weights for several hours, resulting in a firm, sliceable cheese. In contrast, Camembert receives gentle pressing, preserving its creamy interior.

Pressing also influences moisture content, a key factor in ripening and flavor development. Harder cheeses, subjected to longer pressing, have lower moisture levels, slowing down ripening and yielding sharper flavors. Softer cheeses, with higher moisture content due to less pressing, ripen faster and develop milder, more delicate flavors.

Mastering salting and pressing requires attention to detail and an understanding of the desired cheese's characteristics. Experimentation with salt levels and pressing times allows cheesemakers to craft unique profiles, from the salty tang of feta to the buttery richness of Gruyère. Remember, these steps are not merely mechanical processes but artistic interventions that shape the soul of the cheese.

Is the Moon Cheese? Debunking the Myth Once and For All

You may want to see also

Aging and Ripening: Storing cheese in controlled conditions to develop flavor and texture

Aging and ripening are the transformative phases where cheese evolves from a simple curd into a complex, flavorful masterpiece. This process, often overlooked by novice cheesemakers, is where the magic happens—where subtle nuances of taste, aroma, and texture emerge. It’s not just about waiting; it’s about creating the perfect environment for microbial activity and enzymatic reactions to work their wonders. Without proper aging, even the most meticulously crafted cheese remains a shadow of its potential.

To age cheese effectively, precise control over temperature and humidity is non-negotiable. Hard cheeses like Parmesan or Cheddar thrive in cooler conditions, typically between 50°F to 55°F (10°C to 13°C), with humidity levels around 80-85%. In contrast, softer cheeses such as Brie or Camembert require warmer environments, around 50°F to 55°F (10°C to 13°C), but with higher humidity, often near 90-95%. These conditions encourage the growth of specific molds and bacteria that contribute to flavor development. For example, the white rind on Brie is the result of *Penicillium camemberti*, which flourishes in these controlled settings.

Time is another critical factor in aging cheese, and patience is rewarded. Hard cheeses can age for months or even years, with some Parmegianos maturing for over 24 months to achieve their granular texture and nutty flavor. Soft cheeses, however, are ready much sooner—Camembert, for instance, typically ripens in just 3 to 4 weeks. Regularly flipping and brushing the cheese during this period prevents uneven mold growth and ensures even ripening. For home cheesemakers, investing in a dedicated aging fridge or a wine cooler with humidity control can make this process more manageable.

The art of aging also involves monitoring the cheese’s progress. A slight ammonia smell or excessive mold growth indicates improper conditions, while a firm yet yielding texture and deep, complex flavors signal success. For example, a well-aged Gouda will develop a caramelized sweetness and crystalline crunch, while a mature Cheddar will reveal sharp, tangy notes. Experimentation is key—adjusting temperature, humidity, or aging time can yield unique profiles tailored to personal preference.

In essence, aging and ripening are where cheese finds its soul. It’s a delicate balance of science and intuition, requiring attention to detail and a willingness to learn from each batch. Whether you’re crafting a creamy Brie or a robust Gruyère, mastering this step transforms good cheese into extraordinary cheese. With the right conditions and a bit of patience, the rewards are well worth the wait.

Perfect Quesadilla Cheese Amount: Ounces for Ideal Melt and Flavor

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese making typically involves 10 main steps: milk preparation, acidification, coagulation, cutting the curd, stirring and heating, draining the whey, salting, pressing, aging, and packaging.

No, the number of steps can vary depending on the type of cheese. For example, fresh cheeses like ricotta may require fewer steps, while aged cheeses like cheddar involve additional aging and turning processes.

Yes, beginners can start with simplified versions of the process, often focusing on 5-6 key steps: milk preparation, adding coagulants, cutting and draining curds, salting, and basic aging or immediate consumption.