Spawning a bunch of cheese wheels may sound like a whimsical endeavor, but it’s a fascinating process rooted in both culinary tradition and modern innovation. Whether you’re a cheese enthusiast, a food scientist, or simply curious about the magic behind dairy production, understanding how to create multiple cheese wheels involves mastering the art of curdling milk, pressing curds, and aging the final product. From selecting the right milk and cultures to controlling temperature and humidity during maturation, each step plays a crucial role in crafting the perfect wheel. This guide will walk you through the techniques and tools needed to transform humble ingredients into a delightful array of cheese wheels, ready to be enjoyed or shared.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Gather Ingredients: Milk, rennet, bacteria cultures, salt, and cheesecloth are essential for cheese wheel production

- Prepare Milk: Heat milk, add cultures, and let it acidify for curdling

- Coagulate Curds: Add rennet to form curds, then cut and stir gently

- Press and Mold: Drain whey, press curds into molds, and apply weight for shaping

- Age and Store: Cure wheels in controlled humidity and temperature for desired flavor development

Gather Ingredients: Milk, rennet, bacteria cultures, salt, and cheesecloth are essential for cheese wheel production

Milk is the cornerstone of any cheese wheel, but not all milk is created equal. For optimal results, opt for raw, unpasteurized milk from grass-fed cows, goats, or sheep. Pasteurized milk can work, but it often lacks the complexity of flavor and texture that raw milk provides. The fat content matters too—whole milk yields richer, creamier cheeses, while skim milk produces leaner, firmer varieties. Aim for 1 gallon of milk per 1-2 pounds of cheese, depending on the type.

Rennet, a coagulating enzyme, transforms liquid milk into solid curds. Animal rennet is traditional, but vegetarian alternatives like microbial or plant-based rennet are equally effective. Dosage is critical: use 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon of liquid rennet per gallon of milk, diluted in cool, non-chlorinated water. Add it slowly, stirring gently for 1-2 minutes, then let the milk sit undisturbed for 10-20 minutes until the curd forms a clean break. Overusing rennet can lead to a bitter taste, so measure precisely.

Bacteria cultures are the unsung heroes of cheese flavor and texture. Mesophilic cultures thrive at 72-100°F and are ideal for softer cheeses like cheddar or gouda, while thermophilic cultures work at 100-120°F for harder cheeses like parmesan. Direct-set cultures are beginner-friendly, requiring 1/4 teaspoon per gallon of milk. For aged cheeses, consider adding lipase powder (1/8 teaspoon per gallon) to enhance sharpness. Always rehydrate cultures in milk before adding to ensure even distribution.

Salt isn’t just for flavor—it’s a preservative that controls moisture and bacteria growth. Use non-iodized salt (like kosher or cheese salt) to avoid off-flavors. For fresh cheeses, sprinkle salt directly on the curds (1-2% of the milk weight). For aged wheels, brine the cheese in a saturated salt solution (2.5 pounds of salt per gallon of water) for 1-24 hours, depending on size. Too little salt can cause spoilage; too much can overpower the cheese’s natural flavors.

Cheesecloth is the unsung tool of cheese making, but not all cheesecloth is equal. Opt for fine-weave, food-grade cheesecloth to drain curds without losing them. For firmer cheeses, use butter muslin or a cheese mold lined with cloth. After draining, flip the cheese every few hours to ensure even moisture loss. For aged wheels, bandage the cloth tightly around the cheese to create a natural rind. Wash and sanitize cheesecloth after each use to prevent contamination.

Mastering these ingredients is the first step to spawning a bunch of cheese wheels. Each component plays a unique role, and precision in selection and use ensures success. With quality milk, measured rennet, active cultures, balanced salt, and proper cheesecloth, you’re well on your way to crafting wheels that rival those of seasoned cheesemakers.

The Surprising Origin of Money Jack Cheese: A Country Revealed

You may want to see also

Prepare Milk: Heat milk, add cultures, and let it acidify for curdling

Heating milk to the right temperature is the first critical step in transforming it into cheese. Aim for 86°F to 100°F (30°C to 38°C), depending on the cheese type. Too low, and the cultures won’t activate; too high, and you’ll kill them. Use a reliable dairy thermometer—guessing risks ruining the batch. This gentle heat prepares the milk for the cultures, creating an environment where they can thrive and begin their work.

Once the milk reaches the desired temperature, add the cultures—specific bacteria that will acidify the milk. Dosage matters: typically, 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon of culture per gallon of milk. Stir gently but thoroughly to ensure even distribution. These cultures are the unsung heroes of cheesemaking, converting lactose into lactic acid, which lowers the milk’s pH and sets the stage for curdling. Without them, you’re just heating milk, not making cheese.

After adding the cultures, let the milk rest. This is the acidification phase, where the real magic happens. Cover the pot and maintain the temperature for 30 to 60 minutes, depending on the recipe. During this time, the milk will thicken slightly and develop a tangy aroma. Patience is key—rushing this step can lead to weak curds and a lackluster cheese wheel. Think of it as the milk’s transformation period, where it shifts from a liquid to a base for solid cheese.

Practical tip: Use a heating pad or warm water bath to keep the milk at a steady temperature during acidification. Fluctuations can disrupt the process. Also, avoid stirring the milk during this phase, as it can interfere with the cultures’ work. By the end of this step, you’ll have milk ready for the next stage—coagulation—where it will truly begin to resemble cheese. Master this, and you’re well on your way to spawning a bunch of cheese wheels.

Perfect Cheese Platter: Top Picks for Flavorful Pairings and Presentation

You may want to see also

Coagulate Curds: Add rennet to form curds, then cut and stir gently

Rennet is the catalyst that transforms milk into cheese, a process as old as civilization itself. This enzyme complex, derived from the stomachs of ruminant animals or produced through microbial fermentation, triggers the coagulation of milk proteins, primarily casein. When added to warmed milk, rennet initiates a chain reaction: it cleaves kappa-casein, destabilizing the milk’s colloidal structure and causing the liquid to solidify into a gel-like mass. This mass, known as the curd, is the foundation of every cheese wheel. Without rennet or a suitable alternative, milk would remain liquid, and cheese as we know it would not exist.

The art of coagulating curds demands precision. For every 10 liters of milk, a typical dosage ranges from 1 to 2 milliliters of liquid rennet diluted in cool, non-chlorinated water. This mixture should sit for 5–10 minutes to activate fully before adding it to the milk. Stir the rennet into the milk slowly, using an up-and-down motion to distribute it evenly without incorporating air. The milk’s temperature is critical: for most cheeses, it should be between 30–35°C (86–95°F). Too cold, and the rennet won’t work; too hot, and it will denature. After adding the rennet, cover the pot and let it rest undisturbed for 30–60 minutes, depending on the recipe. The curd is ready when it resists a clean break when cut with a knife.

Once the curd has set, cutting and stirring become the next crucial steps. The goal is to release whey while maintaining the curd’s structure. Use a long knife or curd cutter to slice the curd into uniform cubes, typically 1–2 cm in size. Smaller cubes release whey faster, ideal for hard cheeses like cheddar, while larger cubes retain moisture for softer varieties like mozzarella. After cutting, stir the curds gently but consistently for 5–15 minutes. This movement prevents matting and ensures even heating. The curds will shrink and firm up as whey is expelled, a process that can be accelerated by gradually increasing the temperature to 35–40°C (95–104°F).

Mistakes at this stage can ruin the cheese. Overcutting or stirring too aggressively can break the curds into crumbs, leading to a dry, crumbly texture. Undercutting leaves large, uneven curds that don’t knit together properly. Similarly, failing to maintain the correct temperature range can halt the process or cause the curds to toughen. For beginners, it’s helpful to practice with a single gallon of milk before scaling up. Keep a thermometer handy and resist the urge to rush—patience is as essential as precision.

The coagulation and cutting of curds are where the cheese’s destiny is shaped. This stage determines moisture content, texture, and even flavor. Hard cheeses require firmer curds and more whey expulsion, while soft cheeses demand gentler handling and higher moisture retention. By mastering the use of rennet and the technique of cutting and stirring, you gain control over the final product. It’s a delicate balance of science and intuition, but with practice, you’ll be able to spawn cheese wheels that rival those of seasoned cheesemakers.

Unrefrigerated Cheese: 12 Hours Later – Risks and Realities

You may want to see also

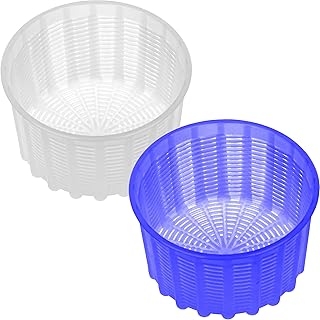

Explore related products

Press and Mold: Drain whey, press curds into molds, and apply weight for shaping

Draining whey from curds is a critical step in cheese making, as it determines the final texture and moisture content of your cheese wheels. After cutting and heating the curds, allow them to settle in a cheesecloth-lined mold. Gently ladle or pour the curds into the mold, ensuring even distribution. The whey will begin to drain naturally, but you can expedite the process by using a perforated mold or tilting the setup slightly. For softer cheeses, drain for 10-15 minutes; harder varieties may require up to an hour. This stage is where the transformation from liquid to solid begins, setting the foundation for the pressing phase.

Pressing curds into molds is both an art and a science, requiring precision to achieve the desired shape and density. Once the whey has drained sufficiently, fold the cheesecloth over the curds and place a follower (a flat, food-safe board) on top. Apply weight gradually, starting with lighter pressure and increasing it over time. For small molds, begin with 5-10 pounds, adjusting based on the cheese type. Harder cheeses like cheddar may need up to 50 pounds of pressure over several hours. Monitor the process, flipping the mold every 30-60 minutes to ensure even shaping. Inconsistent pressure can lead to cracks or uneven texture, so use a cheese press or improvised setup with weights for accuracy.

The application of weight during molding is what gives cheese wheels their characteristic shape and internal structure. For larger wheels, distribute weight evenly using a press with adjustable arms or by placing weights directly on the follower. Soft cheeses like Brie require minimal pressure (2-3 pounds) for 12-24 hours, while semi-hard cheeses like Gouda need 15-20 pounds for 1-2 days. Always refer to specific recipes for timing and pressure guidelines. Too much weight too soon can expel too much whey, resulting in a dry, crumbly texture. Conversely, insufficient pressure may leave the cheese too moist and prone to spoilage.

Practical tips can elevate your pressing and molding process. Use food-grade plastic or stainless steel molds to prevent contamination and ensure easy cleaning. Cheesecloth should be dampened and wrung out before use to prevent it from sticking to the curds. Keep the molding area at a consistent temperature (around 68-72°F) to avoid slowing or accelerating the process. For improvised setups, stack weights on a flat surface above the mold, ensuring stability to prevent accidents. Finally, label molds with the cheese type and date to track progress, especially when making multiple batches simultaneously.

The final takeaway is that pressing and molding are not just functional steps but opportunities to impart character to your cheese wheels. The pressure applied, duration, and technique all influence the outcome, from the rind’s appearance to the interior’s consistency. Experimentation is key—adjust variables like weight and flipping frequency to refine your technique. With practice, you’ll develop an intuition for when curds are ready for the next step, transforming them into perfectly shaped, delicious cheese wheels. Master this stage, and you’ll be one step closer to spawning a bunch of cheese wheels that rival those of seasoned artisans.

Cheese and Spicy Foods: How They Affect Your Stomach's Health

You may want to see also

Age and Store: Cure wheels in controlled humidity and temperature for desired flavor development

The art of aging cheese is a delicate dance between time, temperature, and humidity. Each cheese wheel is a living, breathing entity, transforming as it matures. To unlock the desired flavor profile, precision is key. Ideal aging conditions vary by cheese type: hard cheeses like Parmesan thrive at 50-55°F (10-13°C) and 80-85% humidity, while softer cheeses like Brie prefer 50-54°F (10-12°C) and 90-95% humidity. These controlled environments ensure the cheese develops its unique texture and taste without spoiling.

Consider the aging process as a recipe with specific steps. First, select a dedicated aging space—a cool, dark area like a basement or a specialized cheese cave. Use a hygrometer and thermometer to monitor conditions, adjusting with humidifiers or dehumidifiers as needed. Turn the wheels regularly to prevent mold concentration and ensure even moisture distribution. For example, a 20-pound wheel of cheddar aged at 55°F (13°C) and 85% humidity for 6 months will develop a sharp, nutty flavor, while the same wheel aged for 12 months will become crumbly and intensely savory.

Aging cheese is as much science as it is art, requiring patience and attention to detail. Beginners often overlook the importance of airflow, which prevents mold overgrowth and promotes even curing. A wire rack or slatted shelving system allows air to circulate around the wheels. For those without a dedicated space, a wine fridge can be repurposed, though humidity control may require additional tools like brine-soaked cloths or water trays. Remember, consistency is crucial—fluctuations in temperature or humidity can halt or ruin the aging process.

Comparing aging methods reveals the impact of environment on flavor. Natural caves offer unparalleled complexity due to their microbial ecosystems, but they’re inaccessible to most. Modern aging rooms replicate these conditions with controlled systems, offering reliability. For instance, a wheel of Gruyère aged in a Swiss cave will have earthy, floral notes, while one aged in a controlled room may have a cleaner, more consistent profile. The takeaway? Tailor your setup to the cheese’s needs and your resources, balancing tradition with practicality.

Finally, aging cheese is a commitment, but the rewards are unparalleled. A well-aged wheel tells a story of time and care, its flavor a testament to the process. Whether you’re crafting a batch for personal enjoyment or commercial sale, mastering humidity and temperature control is non-negotiable. Start small, experiment with one or two wheels, and document your observations. Over time, you’ll develop an intuition for the subtle cues that signal perfection. After all, in the world of cheese, patience isn’t just a virtue—it’s the secret ingredient.

Jimmy Dean Ham, Egg, and Cheese Croissant: What Happened?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

There is no scientific or practical method to "spawn" cheese wheels, as cheese is a food product made through a specific manufacturing process, not something that can be spontaneously generated.

Spawning cheese wheels through magic or spells exists only in fantasy or fiction. In reality, cheese production requires milk, bacteria, enzymes, and time.

No machine can instantly spawn cheese wheels. Cheese-making involves curdling milk, pressing curds, and aging, which takes hours to months, depending on the type of cheese.

The quickest way to get a bunch of cheese wheels is to purchase them from a grocery store, cheese shop, or online retailer.

Some video games may include cheats or mods to spawn items like cheese wheels, but this depends on the specific game. Check the game’s forums or cheat guides for details.