Cheese, one of the world’s oldest and most beloved foods, is believed to have been invented over 8,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent region, which includes modern-day Iraq, Syria, and Iran. The discovery likely occurred by accident when milk stored in containers made from the stomachs of animals curdled due to the presence of rennet, a natural enzyme that separates milk into curds and whey. Early herders, noticing that the curdled milk was edible and preserved longer than fresh milk, began intentionally curdling it, laying the foundation for the diverse array of cheeses we enjoy today. This simple yet transformative process marked the beginning of cheese-making, a craft that would spread across cultures and evolve into the global culinary staple it is today.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | Likely originated independently in multiple regions, including the Middle East, Europe, and Central Asia. |

| Time Period | Estimated to have been invented around 8000-3000 BCE. |

| Discovery Method | Accidental discovery, possibly due to the natural curdling of milk in animal stomachs used as containers. |

| Key Ingredients | Milk (from cows, goats, sheep, or buffalo), rennet (or natural curdling agents), and salt. |

| Process | 1. Milk was stored in containers made from animal stomachs, which contained rennet. 2. Rennet caused the milk to curdle, separating into curds and whey. 3. Curds were drained, pressed, and salted to create a primitive form of cheese. |

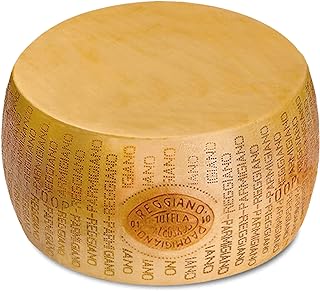

| Early Evidence | Archaeological findings suggest cheese-making in ancient Egypt (around 3000 BCE) and Mesopotamia. |

| Purpose | Initially, cheese was a way to preserve milk and make it more portable and digestible. |

| Types of Early Cheese | Simple, fresh cheeses similar to modern cottage cheese or feta. |

| Cultural Spread | Cheese-making techniques spread through trade, migration, and cultural exchange. |

| Technological Advancements | Over time, methods improved with the use of specific molds, bacteria cultures, and controlled aging processes. |

| Historical Significance | Cheese became a staple food in many cultures, influencing culinary traditions and economies. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ancient Origins: Cheese-making likely began over 8,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent

- Accidental Discovery: Early cheese may have formed from milk stored in animal stomachs

- Early Techniques: Ancient cultures used rennet and bacteria to curdle milk intentionally

- Spread Across Civilizations: Cheese-making spread via trade routes to Europe and Asia

- Evolution of Varieties: Regional differences led to diverse cheese types over centuries

Ancient Origins: Cheese-making likely began over 8,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent

The earliest evidence of cheese-making dates back to around 6,000 BCE in the Fertile Crescent, a region encompassing modern-day Iraq, Syria, and neighboring areas. This discovery was made through the analysis of fatty acids found on ancient pottery fragments, revealing a process that likely involved curdling milk with acid or enzymes. Imagine early herders, perhaps by accident, storing milk in containers made from the stomachs of animals, only to find it transformed into a solid, edible substance—a primitive form of cheese. This innovation was not merely a culinary breakthrough but a survival strategy, as cheese provided a longer-lasting and more portable source of nutrition than fresh milk.

To recreate this ancient process, consider the following steps: Start with raw milk, preferably from sheep or goats, as these were the primary livestock in the Fertile Crescent. Heat the milk gently, then add a natural coagulant like rennet (derived from animal stomachs) or lemon juice. Allow the mixture to curdle, separating into solid curds and liquid whey. Drain the whey and press the curds to form a simple cheese. This method, though rudimentary, mirrors the techniques likely used by early cheese-makers. Experimenting with this process offers a tangible connection to humanity’s culinary past.

The invention of cheese in the Fertile Crescent was deeply intertwined with the Neolithic Revolution, a period marked by the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture and animal domestication. As communities settled and began raising livestock, they needed ways to preserve surplus milk. Cheese emerged as a solution, transforming perishable milk into a storable food source. This innovation not only supported population growth but also facilitated trade and cultural exchange, as cheese could be transported over long distances. Its creation was, in essence, a byproduct of humanity’s growing mastery over its environment.

Comparing ancient cheese to modern varieties highlights both continuity and evolution. Early cheeses were likely unaged, salty, and acidic, lacking the complexity of today’s aged cheddar or creamy brie. Yet, the core principle—separating curds from whey—remains unchanged. Modern cheese-making builds on this foundation, incorporating refinements like specific bacterial cultures, aging techniques, and precise temperature controls. By understanding these ancient origins, we gain a deeper appreciation for the craftsmanship behind every wheel of cheese, whether crafted in a rural village or a state-of-the-art dairy.

Finally, the legacy of ancient cheese-making extends beyond the kitchen, offering insights into human ingenuity and adaptability. The Fertile Crescent’s early herders, faced with the challenge of preserving milk, inadvertently laid the groundwork for one of the world’s most beloved foods. Their discovery underscores a fundamental truth: necessity breeds innovation. Today, as we enjoy a myriad of cheeses, we partake in a tradition that began over 8,000 years ago, a testament to the enduring power of human creativity.

I Run for Cheese" Lululemon: Decoding the Quirky Slogan's Meanin

You may want to see also

Accidental Discovery: Early cheese may have formed from milk stored in animal stomachs

The origins of cheese are shrouded in the mists of prehistory, but one compelling theory suggests it began with a simple, accidental discovery. Imagine early humans, nomadic herders, carrying milk in containers made from animal stomachs—a practical choice given the materials at hand. These stomachs contained rennet, an enzyme complex that coagulates milk, a process essential to cheese-making. Left in the sun or jostled during travel, the milk would have curdled, separating into curds and whey. This unintended transformation, though initially puzzling, likely sparked curiosity rather than disdain. The curds, denser and more portable than liquid milk, would have been easier to store and consume, especially in resource-scarce environments. This accidental experiment laid the foundation for one of humanity’s most enduring culinary innovations.

To replicate this early discovery, consider a hands-on approach. Start with raw milk and a piece of dried animal stomach lining (modern rennet tablets work too). Warm the milk to body temperature (around 37°C or 98.6°F), add a small amount of rennet, and let it sit undisturbed for several hours. The milk will curdle, forming a soft, custard-like mass. Drain the whey, and what remains are the curds—the precursor to cheese. This simple process, though rudimentary, mirrors the conditions under which cheese may have first emerged. It’s a reminder that innovation often arises from necessity and observation, not deliberate intent.

From a practical standpoint, this method offers insights into sustainable food preservation. Early humans would have quickly recognized the curds’ longer shelf life compared to fresh milk, a critical advantage in pre-refrigeration eras. The whey, rich in lactose and proteins, could be fermented into beverages or used as a nutrient source, ensuring nothing went to waste. This dual-purpose approach aligns with modern trends in zero-waste cooking and highlights the ingenuity of our ancestors. For contemporary enthusiasts, experimenting with this technique not only connects us to our culinary roots but also encourages creativity in using every part of an ingredient.

Comparatively, this accidental discovery contrasts sharply with the deliberate, scientific processes of modern cheese-making. Today, precise temperature controls, bacterial cultures, and aging techniques produce a vast array of cheeses, from creamy Brie to sharp Cheddar. Yet, the core principle remains the same: coagulating milk and separating curds from whey. The early method, though crude, underscores the beauty of simplicity. It’s a testament to how even the most sophisticated traditions often begin with humble, unintended beginnings. By understanding this history, we gain a deeper appreciation for the craft and a renewed sense of experimentation in our own kitchens.

Mastering Fruit Cheese Storage: Tips for Freshness and Flavor Preservation

You may want to see also

Early Techniques: Ancient cultures used rennet and bacteria to curdle milk intentionally

The earliest evidence of cheese-making dates back to 6,000 BCE in the Fertile Crescent, where ancient cultures stumbled upon the transformative power of rennet and bacteria. These early cheesemakers, likely shepherds, noticed that milk stored in animal stomachs curdled into a solid, edible mass. This accidental discovery led to intentional experimentation, as they began to harness the enzymes in rennet—a substance found in the stomach lining of ruminants—to coagulate milk. By combining rennet with naturally occurring lactic acid bacteria, they created a controlled environment for curdling, laying the foundation for cheese as we know it today.

To replicate this ancient technique, one would start by sourcing fresh, unpasteurized milk, as it contains the necessary bacteria for fermentation. Next, extract rennet from the fourth stomach chamber of a young ruminant, such as a calf or lamb. Traditionally, this involved drying the stomach lining and soaking it in water to create a liquid extract. For every gallon of milk, add approximately 1–2 teaspoons of this rennet solution, stirring gently to distribute the enzymes evenly. Allow the mixture to rest at a stable temperature (around 30°C or 86°F) for 30–60 minutes, until a firm curd forms. This method not only separates the curds from the whey but also introduces complex flavors through bacterial fermentation.

Comparing this to modern techniques highlights the ingenuity of ancient cheesemakers. Today, industrial cheese production often relies on standardized bacterial cultures and synthetic rennet, prioritizing consistency over the nuanced flavors achieved through traditional methods. Ancient cultures, however, embraced variability, allowing regional bacteria to influence the cheese’s character. For instance, cheeses from different areas of Mesopotamia or Egypt likely had distinct tastes due to unique microbial environments. This diversity underscores the importance of place-based practices in early cheese-making.

A practical tip for modern enthusiasts seeking to recreate these techniques is to experiment with raw milk from local sources, as it carries region-specific bacteria. Pair this with homemade rennet extract or natural alternatives like fig sap, which contains enzymes similar to those in animal rennet. While the process requires patience and attention to detail, the result is a cheese that connects you to millennia-old traditions. By understanding these early techniques, we not only appreciate the origins of cheese but also gain insight into the resourcefulness of ancient cultures in transforming simple ingredients into something extraordinary.

Was Cheese a Dairy Accident? Unraveling the 4000-Year-Old Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spread Across Civilizations: Cheese-making spread via trade routes to Europe and Asia

The Silk Road, a network of ancient trade routes connecting the East and West, wasn't just a conduit for spices and silk—it was also a highway for cheese-making knowledge. As merchants traveled between Europe and Asia, they carried with them not only goods but also techniques and traditions. This cultural exchange facilitated the spread of cheese-making practices, adapting and evolving as they crossed borders. For instance, the Central Asian technique of using rennet from sheep stomachs likely influenced European methods, while the Mediterranean practice of salting cheese for preservation found its way eastward.

Consider the practical implications of this spread. Traders needed cheese that could withstand long journeys, so harder, more durable varieties like Pecorino Romano in Italy or the aged cheeses of the Middle East became staples. These cheeses were not just food but also currency, often used to barter for other goods. To replicate this durability in your own cheese-making, aim for a moisture content below 40% by pressing the curds firmly and aging the cheese for at least 6 months. This ensures it can survive travel, just as it did centuries ago.

The persuasive argument here is clear: cheese-making’s global spread was a testament to its adaptability and value. As civilizations encountered new climates and resources, they modified techniques to suit local conditions. In the humid regions of Southeast Asia, for example, molds were embraced rather than avoided, leading to the creation of unique varieties like Indonesia’s *keju* or Vietnam’s *bánh canh*. This adaptability underscores cheese’s role not just as a food but as a cultural bridge, fostering exchange and innovation across continents.

A comparative analysis reveals how trade routes accelerated cheese diversity. While the Middle East favored soft, brined cheeses like *labneh* and *feta*, Central Asia developed harder, smoked varieties suited to nomadic lifestyles. Europe, meanwhile, refined techniques for aged cheeses like Cheddar and Parmesan, which became symbols of regional identity. To appreciate this diversity, experiment with recipes from different regions, noting how ingredients and methods reflect local environments. For instance, use goat’s milk for a Mediterranean-style cheese or add local herbs for an Asian-inspired twist.

Finally, the takeaway is this: cheese-making’s journey across civilizations was not just a story of survival but of transformation. Each culture that encountered cheese left its mark, creating a global tapestry of flavors and techniques. By understanding this history, modern cheese-makers can draw inspiration from ancient practices while innovating for contemporary tastes. Whether you’re aging a wheel of Gouda or crafting a batch of *paneer*, you’re participating in a tradition that has spanned millennia and continents.

Perfectly Filled Croissants: A Cheesy Baking Guide Before Baking

You may want to see also

Evolution of Varieties: Regional differences led to diverse cheese types over centuries

The humble origins of cheese, likely discovered when milk stored in animal stomachs curdled, set the stage for a culinary revolution. As this accidental creation spread across regions, local conditions and cultural preferences began to shape its evolution. The result? A dazzling array of cheese varieties, each a testament to the ingenuity of its creators and the unique characteristics of its place of origin.

Consider the climate. In cooler, damp regions like Northern Europe, harder cheeses such as Cheddar and Gouda emerged. These varieties benefited from slower aging processes, allowing for the development of complex flavors and longer shelf lives. In contrast, warmer Mediterranean climates fostered the creation of softer, fresher cheeses like Feta and Ricotta. These cheeses, often made with sheep or goat milk, were ideal for immediate consumption and paired well with local produce.

Milk source played a pivotal role as well. In areas with abundant cow herds, such as Switzerland and the Netherlands, cheeses like Emmental and Edam became staples. Meanwhile, regions with strong sheep or goat herding traditions, like Greece and Spain, specialized in cheeses such as Manchego and Halloumi. Each animal’s milk brought distinct textures and tastes, further diversifying the cheese landscape.

Cultural practices and available resources also left their mark. In France, the addition of molds and bacteria led to the creation of iconic cheeses like Brie and Camembert. In Italy, stretching techniques gave rise to Mozzarella, a key ingredient in pizza and pasta dishes. These innovations were not random but deliberate responses to local needs and tastes, showcasing how regional differences drove the evolution of cheese varieties.

To appreciate this diversity, consider experimenting with pairing cheeses to their origins. For instance, serve a sharp English Cheddar with a full-bodied red wine, or enjoy a creamy Greek Feta in a salad with olives and tomatoes. Understanding the regional influences behind each cheese not only enhances your culinary experience but also connects you to centuries of tradition and craftsmanship.

Mastering Cheese Slicing: Perfect Wedge Cuts for Every Occasion

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese was likely first invented accidentally around 8000 years ago when milk stored in containers made from the stomachs of animals curdled due to the presence of rennet, an enzyme that separates milk into curds and whey.

There is no single person credited with the discovery of cheese. It is believed to have been independently discovered by various ancient civilizations as they domesticated animals and stored milk in natural containers.

Archaeological evidence, such as strainers with milk residue and murals depicting cheese-making, suggests that cheese production dates back to at least 5500 BCE in regions like Poland and the Middle East.

Early cheese was likely simple, unsalted, and unaged, resembling fresh cheeses like cottage cheese or ricotta. Modern cheese varieties evolved through experimentation with aging, molds, and additional ingredients.