The question Is a block of cheese a loaf of milk? may seem absurd at first glance, but it invites a deeper exploration of the transformation of raw ingredients into processed foods. Cheese, a solid dairy product, is crafted through the coagulation and fermentation of milk, a liquid. While both share a common origin, the processes they undergo—curdling, pressing, and aging for cheese—create distinct textures, flavors, and forms. Thus, a block of cheese is not a loaf of milk but rather a refined, concentrated version of it, highlighting the fascinating journey from raw material to culinary staple.

Explore related products

$51.99 $54.99

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Cheese and Milk: Clarify if cheese is a solid form of milk

- Production Process Comparison: Examine how cheese and milk are made differently

- Nutritional Differences: Analyze the nutritional content of cheese versus milk

- Cultural Perceptions: Explore how cheese and milk are viewed in various cultures

- Storage and Shelf Life: Compare how cheese and milk are stored and preserved

Definition of Cheese and Milk: Clarify if cheese is a solid form of milk

Cheese and milk are fundamentally different, yet intrinsically linked. Milk, in its raw form, is a liquid nutrient powerhouse, composed primarily of water, fats, proteins (casein and whey), lactose, and minerals. Cheese, on the other hand, is a concentrated, solidified product derived from milk through a process that involves curdling, draining, and aging. This transformation raises the question: Is cheese merely a solid form of milk? To answer this, we must dissect the processes that turn milk into cheese and examine the resulting changes in composition and structure.

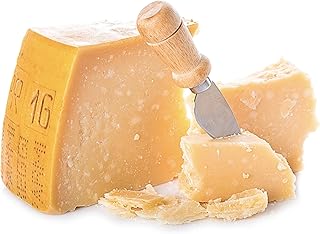

Consider the steps involved in cheese making: coagulation, curd formation, pressing, and aging. During coagulation, enzymes or acids cause milk proteins to clump together, separating into curds (solids) and whey (liquid). Pressing removes excess moisture, further solidifying the curds. Aging allows bacteria and molds to break down proteins and fats, developing flavor and texture. This process significantly alters milk’s original state, reducing its water content from approximately 87% in whole milk to as low as 30–40% in hard cheeses like Parmesan. Thus, while cheese originates from milk, it is not merely a solid version of it; it is a transformed product with distinct characteristics.

From a nutritional standpoint, cheese and milk differ markedly. One cup of whole milk (240 ml) contains about 150 calories, 8 grams of protein, and 8 grams of fat. In contrast, one ounce (28 grams) of cheddar cheese provides 110 calories, 7 grams of protein, and 9 grams of fat. Cheese is more calorie-dense due to its lower water content and higher fat concentration. Additionally, the aging process in cheese reduces lactose levels, making it more tolerable for those with lactose intolerance. These differences highlight that cheese is not just milk in solid form but a nutritionally altered product.

To illustrate the transformation, imagine milk as a raw ingredient and cheese as a finished dish. Just as flour becomes bread through baking, milk becomes cheese through curdling and aging. While both share a common base, the end products serve different purposes and possess unique properties. Cheese’s solidity, flavor complexity, and extended shelf life are attributes milk lacks. Therefore, while cheese is derived from milk, it is inaccurate to label it as a mere solid form of milk.

In practical terms, understanding this distinction is useful for cooking and dietary planning. For instance, substituting cheese for milk in recipes requires adjustments for texture and moisture content. One cup of grated cheese (about 110 grams) can replace one cup of milk, but additional liquid or fat may be needed to balance the dish. Similarly, individuals monitoring fat or calorie intake should note that cheese provides more concentrated nutrients per gram than milk. This knowledge empowers informed choices, whether in the kitchen or at the grocery store.

Does Individually Wrapped Cheese Require Refrigeration? Facts and Tips

You may want to see also

Production Process Comparison: Examine how cheese and milk are made differently

Cheese and milk, though both dairy products, undergo vastly different production processes that transform their composition, texture, and shelf life. Milk, in its simplest form, is a raw product obtained directly from animals like cows, goats, or sheep. The process involves milking, immediate cooling to 4°C (39°F) to inhibit bacterial growth, and pasteurization, where it’s heated to 72°C (161°F) for 15 seconds to kill pathogens. This minimal processing preserves milk’s liquid state and nutritional profile, making it ready for consumption within days. Cheese, however, begins with milk but is subjected to a series of complex transformations. The first step is coagulation, where rennet or bacterial cultures are added to curdle the milk, separating it into solid curds and liquid whey. This marks the beginning of cheese’s journey from liquid to solid.

The curds are then cut, stirred, and heated in a process called scalding, which expels more whey and determines the cheese’s final texture. For example, softer cheeses like mozzarella are scalded at lower temperatures (around 35°C or 95°F), while harder cheeses like cheddar are heated to 40°C (104°F) or higher. After scalding, the curds are pressed into molds to remove excess whey and form a cohesive mass. This is followed by salting, either by brining or dry-salting, which enhances flavor and acts as a preservative. The final step is aging, where the cheese is stored in controlled environments for weeks to years, allowing microbial activity and enzymatic reactions to develop its unique flavor and texture. This aging process is absent in milk production, highlighting a fundamental difference in their manufacturing.

From a practical standpoint, the production of cheese requires significantly more time, labor, and resources compared to milk. While milk can be processed and packaged within hours, cheese production spans days to years, depending on the variety. For instance, fresh cheeses like ricotta take only a day to make, whereas aged cheeses like Parmesan require over a year of maturation. This extended process not only alters the product’s characteristics but also its nutritional content. Cheese is more concentrated in fat, protein, and calories due to the removal of whey, whereas milk retains its original nutrient distribution. Understanding these differences helps consumers appreciate why cheese is often more expensive and why it offers a distinct culinary experience compared to milk.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both products start with the same raw material, their production methods diverge sharply. Milk’s process is linear and focused on preservation, whereas cheese’s involves deliberate manipulation to create a new product. For those interested in home cheesemaking, the key takeaway is that small adjustments in temperature, coagulation time, or aging conditions can dramatically alter the outcome. For example, using 0.05% rennet by weight of milk and maintaining a temperature of 30°C (86°F) during coagulation will yield a different texture than using 0.1% rennet at 32°C (90°F). Conversely, milk production is more standardized, with strict guidelines to ensure safety and consistency. This contrast underscores why a block of cheese cannot be equated to a loaf of milk—they are distinct products born from the same source but shaped by vastly different processes.

Sargento Recall: Does Natural Cheese Colby Jack Get Affected?

You may want to see also

Nutritional Differences: Analyze the nutritional content of cheese versus milk

Cheese and milk, both dairy staples, offer distinct nutritional profiles that cater to different dietary needs. A single cup of whole milk contains approximately 8 grams of protein, while an equivalent weight of cheddar cheese provides about 25 grams. This disparity highlights cheese’s role as a concentrated protein source, ideal for muscle repair and satiety. However, this concentration comes at a cost: cheese retains more fat and sodium during processing, with cheddar containing 9 grams of fat and 174 mg of sodium per ounce, compared to milk’s 8 grams of fat and 122 mg of sodium per cup. For those monitoring calorie intake, cheese’s higher density—400 calories per 3-ounce serving versus 150 calories in a cup of milk—is a critical consideration.

To maximize nutritional benefits, consider age and health goals. Children aged 1–8 require calcium for bone development, making milk’s 300 mg per cup a suitable choice. Adults over 50, at risk for osteoporosis, may benefit from cheese’s 200 mg of calcium per ounce, paired with vitamin D-fortified milk to enhance absorption. For weight management, opt for low-fat milk or part-skim mozzarella, which reduces fat intake without sacrificing protein. Athletes, however, might prioritize cheese’s higher protein content post-workout, balancing it with hydration from milk’s fluid base.

A comparative analysis reveals trade-offs in micronutrients. Milk is a superior source of vitamin B12 (1.1 mcg per cup) and potassium (380 mg), essential for nerve function and blood pressure regulation. Cheese, on the other hand, offers more phosphorus (135 mg per ounce) and zinc (1.3 mg), supporting bone health and immune function. Lactose-intolerant individuals may tolerate cheese better due to its lower lactose content, though hard cheeses like Swiss or Parmesan are preferable over softer varieties like ricotta. Pairing cheese with lactose-free milk ensures a balanced intake of both macro and micronutrients.

Practical tips can help integrate these insights into daily routines. For breakfast, swap a slice of cheddar (110 calories, 7g protein) for a tablespoon of cream cheese (50 calories, 1g protein) on whole-grain toast to boost protein without excess fat. In smoothies, blend Greek yogurt (15g protein per 6 oz) with almond milk for a lactose-friendly, nutrient-dense option. When cooking, use milk in soups for creaminess without the sodium spike of cheese. For snacks, pair an ounce of cheese with an apple to balance fat with fiber, ensuring sustained energy. Tailoring choices to specific needs transforms these dairy products from mere ingredients into strategic nutritional tools.

Pimento Cheese Paradise: Which Country Claims This Creamy Snack?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cultural Perceptions: Explore how cheese and milk are viewed in various cultures

Cheese and milk, though derived from the same source, are perceived and utilized vastly differently across cultures. In France, cheese is an art form, with over 400 varieties celebrated in daily meals and haute cuisine. Milk, while consumed, takes a backseat to its solidified counterpart, often reserved for breakfast or coffee. Contrast this with India, where milk is sacred, central to religious rituals and daily sustenance, while cheese remains a rarity, limited to specific regions like Goa or the Himalayas. This divergence highlights how cultural priorities shape the role of dairy in society.

Consider the nomadic tribes of Mongolia, where fermented mare’s milk (airag) is a staple, yet cheese is virtually nonexistent. Here, milk’s liquid form is prized for its nutritional density and portability in harsh climates. Meanwhile, in Italy, cheese like Parmigiano-Reggiano is aged for years, becoming a luxury item, while milk is often overshadowed by its transformed state. These examples illustrate how environmental factors and historical traditions dictate whether milk or cheese takes precedence in a culture’s diet.

From a nutritional standpoint, the transformation of milk into cheese alters its cultural value. In Scandinavian countries, high-fat cheeses like Brunost are cherished for their energy content, ideal for cold climates. Conversely, in East African cultures, fermented milk products like mursik are favored for their digestibility and probiotic benefits. Age plays a role too: in many Mediterranean cultures, children are encouraged to consume milk for growth, while adults shift to cheese as a more sophisticated, versatile food. This shift underscores how life stages influence cultural perceptions of dairy.

To integrate these cultural insights practically, consider experimenting with dairy in context. For instance, if hosting a French-themed dinner, pair a selection of cheeses with wine, emphasizing their artisanal qualities. In contrast, for an Indian-inspired meal, incorporate paneer or ghee, but prioritize milk-based lassi as a refreshing beverage. Understanding these cultural nuances not only enriches culinary experiences but also fosters appreciation for the diverse ways dairy is valued globally. The key takeaway? Cheese and milk are not just foods—they are cultural symbols, shaped by history, geography, and human ingenuity.

Havarti Cheese Fat Content: Grams of Fat per Serving Revealed

You may want to see also

Storage and Shelf Life: Compare how cheese and milk are stored and preserved

Cheese and milk, both dairy products, diverge sharply in their storage requirements and shelf lives, reflecting their distinct transformations from raw milk. Milk, in its liquid form, is highly perishable, requiring refrigeration at temperatures below 4°C (39°F) to slow bacterial growth. Once opened, it typically lasts 5–7 days, though ultra-pasteurized varieties can extend to 2–3 weeks due to higher heat treatment. Cheese, however, undergoes fermentation and aging, which not only alters its texture and flavor but also enhances its longevity. Hard cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan can last 3–4 weeks in the refrigerator, while softer varieties like Brie or mozzarella are best consumed within 1–2 weeks. For long-term storage, hard cheeses can be frozen for up to 6 months, though this may affect texture.

The preservation techniques for these products further highlight their differences. Milk is often homogenized to prevent cream separation and pasteurized to kill pathogens, but these processes do not eliminate spoilage bacteria entirely. Cheese, on the other hand, benefits from natural preservatives like salt and lactic acid produced during fermentation. Waxed or vacuum-sealed packaging can extend cheese’s shelf life by limiting exposure to air and moisture, which are critical factors in mold growth. Milk, in contrast, relies on opaque containers to block light and airtight seals to prevent contamination, but its preservation is inherently more fragile.

From a practical standpoint, storing cheese and milk involves distinct considerations. Cheese should be wrapped in specialty paper or wax paper to allow it to breathe, preventing moisture buildup that can lead to spoilage. Milk, however, must remain sealed in its original container until opened, and any transfer to another vessel should be minimized to avoid introducing bacteria. Both products benefit from being stored in the coldest part of the refrigerator, but cheese can also be kept in a cooler, drier environment like a wine fridge for optimal aging. For those looking to maximize freshness, freezing milk in ice cube trays for later use in cooking or baking is a viable option, though cheese’s texture may suffer if frozen and thawed.

The shelf life of cheese and milk also intersects with their culinary uses. Milk’s short lifespan makes it ideal for immediate consumption or use in recipes where freshness is key, such as custards or pancakes. Cheese’s longer shelf life, particularly for aged varieties, allows it to be a staple in pantries for extended periods, ready for sandwiches, charcuterie boards, or grating over pasta. Understanding these storage nuances not only reduces food waste but also ensures that both products are enjoyed at their peak quality. Whether you’re preserving a block of cheddar or a gallon of milk, the right techniques can make all the difference.

Chuck E. Cheese vs. Shane Dawson: The Lawsuit That Wasn't

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a block of cheese is not a loaf of milk. Cheese is a solid dairy product made from milk through a process of curdling and aging, while milk is a liquid.

People often compare a block of cheese to a loaf of milk humorously or metaphorically to highlight the transformation of milk into cheese. It’s a playful way to emphasize that cheese is derived from milk.

In a sense, yes. Cheese is made by curdling milk and removing whey, resulting in a solidified product. However, it’s not accurate to call it a "loaf of milk" since cheese has distinct properties and uses compared to milk.

Yes, it is correct. Cheese is made from milk through processes like coagulation, draining, and aging. Milk is the primary ingredient in cheese production.