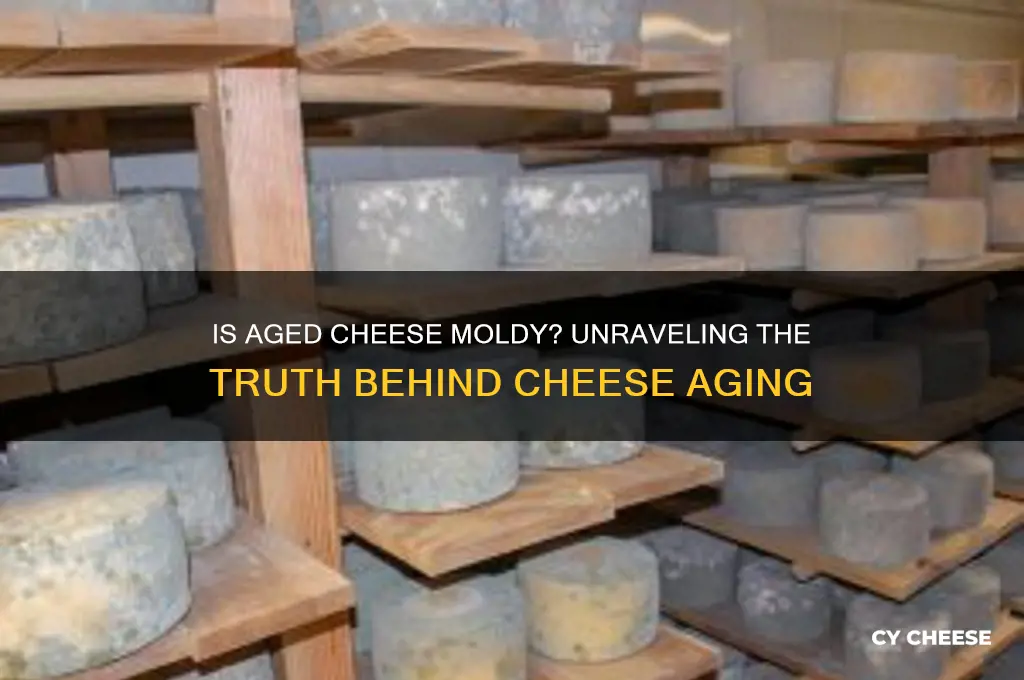

Aged cheese often raises questions about its safety and quality, particularly whether it is moldy. While some aged cheeses, like blue cheese, intentionally contain specific molds as part of their production process, not all aged cheeses are moldy. The aging process itself does not inherently involve mold; instead, it involves controlled environments where bacteria and enzymes break down the cheese, enhancing its flavor and texture. However, if aged cheese develops visible mold that was not part of its intended production, it may indicate spoilage. Understanding the difference between intentional mold in certain cheeses and unintended mold growth is crucial for determining whether aged cheese is safe to consume.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Aged cheese is cheese that has been stored and matured over time, often for several months to years, to develop complex flavors and textures. |

| Mold Presence | Some aged cheeses have mold as part of their natural aging process, either on the surface (e.g., Brie, Camembert) or internally (e.g., Blue Cheese). |

| Intentional Mold | Mold in aged cheese is often intentional and controlled, contributing to flavor, texture, and appearance. |

| Unintentional Mold | Unintentional mold on aged cheese (e.g., due to improper storage) can indicate spoilage and should be avoided. |

| Safety | Intentionally molded aged cheeses are safe to eat when properly produced and stored. Unintentional mold may be harmful. |

| Texture | Mold in aged cheese can create creamy, crumbly, or veined textures, depending on the type. |

| Flavor | Mold contributes to earthy, nutty, tangy, or pungent flavors in aged cheeses. |

| Examples | Brie, Camembert, Blue Cheese, Gorgonzola, Roquefort. |

| Storage | Aged cheeses should be stored in a cool, humid environment to prevent unwanted mold growth. |

| Appearance | Mold in aged cheese can appear as white, blue, or green veins or a bloomy rind. |

| Health Benefits | Mold in aged cheese can introduce probiotics and enzymes beneficial for digestion. |

| Spoilage Signs | Off odors, sliminess, or discoloration (beyond typical mold) indicate spoilage. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Natural Mold Growth: Aged cheese develops mold as part of its aging process, enhancing flavor and texture

- Safe vs. Unsafe Mold: Controlled mold in aged cheese is safe; uncontrolled mold can be harmful

- Types of Cheese Mold: Common molds include Penicillium, Geotrichum, and others, each adding unique characteristics

- Mold Removal Tips: Surface mold on hard cheeses can be cut off, but soft cheeses should be discarded

- Health Benefits of Mold: Beneficial molds in aged cheese can aid digestion and boost immunity

Natural Mold Growth: Aged cheese develops mold as part of its aging process, enhancing flavor and texture

Aged cheeses like Brie, Camembert, and blue cheese owe their distinctive flavors and textures to a carefully managed mold growth process. Unlike the fuzzy green invader that ruins forgotten leftovers, these molds are intentional, cultivated partners in the aging process. Specific strains, such as *Penicillium camemberti* and *Penicillium roqueforti*, are introduced to the cheese either by direct inoculation or through controlled exposure to mold-rich environments. This isn’t spoilage—it’s transformation. The molds break down proteins and fats, releasing complex compounds that create the cheese’s signature tanginess, creaminess, or crumbly texture.

To achieve this, cheesemakers follow precise steps. First, the cheese is inoculated with mold spores, either by spraying the surface or mixing them into the curd. Next, the cheese is aged in temperature- and humidity-controlled environments, typically between 45°F and 55°F with 85–95% humidity. These conditions encourage the mold to grow slowly and predictably, ensuring it contributes to flavor development rather than overwhelming the cheese. For example, Brie’s white rind forms over 4–6 weeks, while blue cheese’s veins develop as air is introduced to the interior, allowing the mold to flourish internally.

While natural mold growth is essential, it’s not without risks. Uncontrolled conditions can lead to off-flavors or harmful molds. Cheesemakers monitor the process closely, often turning or brushing the cheeses to prevent unwanted mold species from taking hold. Home enthusiasts attempting to age cheese should invest in a dedicated aging fridge or cooler to maintain consistent conditions. Avoid aging cheese in a standard kitchen fridge, as its low humidity can dry out the cheese or encourage surface cracking.

The takeaway? Mold on aged cheese isn’t a defect—it’s a feature. When you see the white rind on Camembert or the blue veins in Stilton, you’re witnessing the result of a deliberate, science-backed process. Embrace the mold as part of the cheese’s story, a testament to the craftsmanship that turns simple curds into a culinary masterpiece. Just ensure the mold is the right kind—if it’s green, pink, or black and not part of the cheese’s design, discard it. Otherwise, savor the complexity that only natural mold growth can provide.

To Peel or Not: The Gouda Rind Debate Explored

You may want to see also

Safe vs. Unsafe Mold: Controlled mold in aged cheese is safe; uncontrolled mold can be harmful

Aged cheeses like Gruyère, Gorgonzola, and Camembert owe their distinctive flavors and textures to controlled mold growth. These molds, such as *Penicillium camemberti* or *Penicillium roqueforti*, are intentionally introduced during production. They break down proteins and fats, creating complex flavors and creamy interiors. This process occurs in tightly regulated environments, ensuring the mold remains safe and beneficial. The key lies in the specific strains used, which are non-toxic and incapable of producing harmful mycotoxins. Without this controlled mold, aged cheeses would lack their signature character.

Contrast this with uncontrolled mold, which can turn a culinary delight into a health hazard. Unwanted molds, like *Aspergillus* or *Fusarium*, can grow on cheese stored improperly—think temperatures above 40°F (4°C) or exposure to air. These molds may produce mycotoxins, such as aflatoxins, which are linked to liver damage and cancer. Unlike controlled molds, these strains are unpredictable and can spread rapidly, often visible as fuzzy, discolored patches. A single speck of uncontrolled mold can compromise an entire piece of cheese, as toxins may permeate beyond the visible area.

Distinguishing between safe and unsafe mold requires attention to detail. Controlled mold in aged cheeses appears as uniform veins (like in blue cheese) or a thin, white rind (as in Brie). It contributes to the cheese’s aroma and taste without causing spoilage. Unsafe mold, however, looks irregular, often green, black, or pink, and may have a musty odor. If you spot such mold on any cheese—aged or not—discard the entire piece, as toxins can penetrate deeply. When in doubt, err on the side of caution.

To prevent uncontrolled mold, store aged cheeses properly. Wrap them in wax or parchment paper, not plastic, which traps moisture. Keep them in the coldest part of the refrigerator (around 35°F to 38°F or 2°C to 3°C) and consume within recommended timelines—hard cheeses like Parmesan last 3-4 weeks, while soft cheeses like Camembert should be eaten within a week of opening. For longer storage, freeze hard cheeses (though texture may suffer), but never freeze soft or mold-ripened varieties. These steps ensure the mold remains a culinary asset, not a health risk.

Understanding the difference between controlled and uncontrolled mold transforms apprehension into appreciation. Controlled mold is a craftsman’s tool, shaping the essence of aged cheeses. Uncontrolled mold is a warning sign, demanding vigilance. By recognizing the signs and following storage guidelines, you can safely enjoy the rich, complex flavors of aged cheeses while avoiding the dangers of harmful molds. It’s not about fear of mold, but respect for its power—both in creation and destruction.

Mastering Commander Nial: Easy Cheese Strategies for Quick Victory

You may want to see also

Types of Cheese Mold: Common molds include Penicillium, Geotrichum, and others, each adding unique characteristics

Aged cheese often features mold as an integral part of its development, but not all molds are created equal. Among the most common are Penicillium, Geotrichum, and others, each contributing distinct flavors, textures, and aromas. These molds are not merely accidental growths but carefully selected microorganisms that transform milk into complex, prized cheeses. Understanding their roles reveals why moldy cheese is not only safe but celebrated in culinary traditions worldwide.

Penicillium, for instance, is the star behind classics like Brie, Camembert, and blue cheeses such as Stilton and Gorgonzola. In Brie and Camembert, *Penicillium camemberti* forms a velvety white rind, breaking down the cheese’s interior to create a creamy, buttery texture. For blue cheeses, *Penicillium roqueforti* is introduced, creating veins of mold that impart sharp, tangy, and slightly spicy notes. This mold thrives in oxygen-rich environments, which is why blue cheese is pierced during aging to encourage its growth. Interestingly, *Penicillium* molds produce penicillin, but the type used in cheese is different from the antibiotic strain, making it safe for consumption.

Geotrichum, on the other hand, is responsible for the distinct characteristics of cheeses like Saint-Marcellin and Neufchâtel. *Geotrichum candidum* forms a thin, powdery rind that softens the cheese from the outside in, resulting in a smooth, spreadable interior. This mold works in tandem with bacteria to create a mild, nutty flavor and a slightly tangy finish. Unlike *Penicillium*, *Geotrichum* prefers cooler temperatures and higher humidity, making it ideal for softer, surface-ripened cheeses.

Other molds, such as *Mucor* and *Scopulariopsis*, play lesser-known but equally important roles. *Mucor* is often used in the early stages of aging to break down the cheese’s structure quickly, preparing it for further mold or bacterial activity. *Scopulariopsis*, though less common, can contribute earthy, mushroom-like flavors in certain aged cheeses. Each mold’s impact depends on factors like temperature, humidity, and the cheese’s pH level, which cheesemakers meticulously control to achieve desired outcomes.

Practical tips for handling moldy cheese include storing it properly—wrapping it in wax or parchment paper to allow it to breathe, and keeping it in the refrigerator at 50–55°F (10–13°C) for optimal aging. If surface mold appears on hard cheeses like Cheddar, simply cut off a 1-inch margin around the moldy spot; for soft cheeses, discard them if mold is present, as it can penetrate deeply. Understanding these molds not only demystifies aged cheese but also highlights the artistry and science behind its creation.

Does In-N-Out Offer Pepper Jack Cheese? A Menu Breakdown

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mold Removal Tips: Surface mold on hard cheeses can be cut off, but soft cheeses should be discarded

Surface mold on aged hard cheeses doesn’t necessarily spell doom. Unlike soft cheeses, which lack a dense structure to prevent mold penetration, hard cheeses like Parmesan, Cheddar, or Gouda can often be salvaged. The key lies in their lower moisture content and denser texture, which confines mold growth to the surface. To safely remove mold, cut off at least one inch around and below the affected area using a clean knife. Ensure the blade penetrates deep enough to eliminate all visible mold and its microscopic roots. This method preserves the majority of the cheese while eliminating the risk of consuming harmful spores.

However, not all molds are created equal. While common molds like *Penicillium* (used in blue cheese) are generally harmless, others can produce toxic compounds called mycotoxins. If the mold appears fuzzy, multicolored, or spreads extensively, discard the cheese entirely. Even hard cheeses can become compromised if mold penetrates too deeply or if the cheese is improperly stored. Always inspect the cheese thoroughly before attempting removal, and trust your instincts—if it looks or smells off, it’s better to err on the side of caution.

Soft cheeses, on the other hand, demand a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to mold. Brie, Camembert, goat cheese, and other high-moisture varieties provide an ideal environment for mold to thrive and spread rapidly. Their creamy texture allows mold to infiltrate easily, making surface removal ineffective. Discarding moldy soft cheese is non-negotiable, as consuming it can lead to foodborne illness or allergic reactions. No amount of cutting or scraping can guarantee safety, so prioritize health over frugality in these cases.

Proper storage is your best defense against mold on any cheese. Hard cheeses should be wrapped in wax or parchment paper, then stored in the refrigerator at 35–40°F (2–4°C). Soft cheeses require airtight containers or specialized cheese paper to maintain humidity without promoting mold growth. Avoid plastic wrap, as it traps moisture and accelerates spoilage. Regularly inspect your cheese for early signs of mold, and always use clean utensils to prevent cross-contamination. With these precautions, you can extend the life of your cheese and minimize waste.

In summary, while hard cheeses can often be saved by cutting away mold, soft cheeses must be discarded at the first sign of contamination. Understanding the structural differences between these cheeses and adopting proper storage practices are essential for both safety and enjoyment. When in doubt, remember: hard cheeses may get a second chance, but soft cheeses never do.

Mastering Stuffed Burgers: Tips to Keep Cheese Melty Inside

You may want to see also

Health Benefits of Mold: Beneficial molds in aged cheese can aid digestion and boost immunity

Aged cheeses like Roquefort, Camembert, and Gorgonzola owe their distinctive flavors and textures to specific molds, such as *Penicillium roqueforti* and *Penicillium camemberti*. Contrary to common concerns, these molds are not only safe but also contribute to health benefits. The controlled fermentation process in aged cheeses ensures that harmful bacteria are inhibited while beneficial molds thrive, transforming milk into a nutrient-rich food with unique properties.

From a digestive perspective, the molds in aged cheese produce enzymes that break down lactose and proteins, making these cheeses easier to digest for individuals with mild lactose intolerance. For example, the lipase enzymes in blue cheese help hydrolyze fats, aiding in their absorption. Incorporating small portions (around 30–50 grams per day) of mold-ripened cheeses into meals can support gut health by reducing bloating and discomfort. Pairing these cheeses with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or fresh fruit maximizes their digestive benefits.

Beyond digestion, the molds in aged cheese can enhance immune function. Certain strains of *Penicillium* produce bioactive compounds with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Studies suggest that regular consumption of these cheeses may stimulate the production of immune cells and improve the body’s response to pathogens. For instance, a 2019 study published in *Frontiers in Microbiology* found that compounds from *Penicillium* molds can modulate gut microbiota, promoting a balanced immune system. Adults can benefit from including aged cheeses in their diet 2–3 times per week, though moderation is key due to their higher sodium and fat content.

However, not all molds are created equal. While the molds in aged cheese are beneficial, accidental mold growth on other foods can be harmful. It’s crucial to distinguish between intentionally molded cheeses and spoiled products. Always purchase aged cheeses from reputable sources and store them properly—wrap in wax or parchment paper, not plastic, to allow breathing. For those with mold allergies or compromised immune systems, consult a healthcare provider before consuming mold-ripened cheeses.

Incorporating aged cheeses into your diet is a flavorful way to harness the health benefits of beneficial molds. Start with small servings to gauge tolerance, and experiment with varieties like Brie or Cheddar to find your preference. By understanding the role of these molds, you can appreciate aged cheese not just as a culinary delight, but as a functional food that supports digestion and immunity.

Can Dogs Eat Cheese? A Guide to Safe Snacking for Your Pup

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Not necessarily. While some aged cheeses may develop mold as part of their aging process, not all aged cheeses are moldy. Mold is intentionally used in certain types of cheese (like blue cheese) but is not present in others.

No, aged cheese does not always have visible mold. Many aged cheeses, such as cheddar or Parmesan, do not have visible mold and are safe to eat.

It depends on the type of cheese. Hard aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan can have mold cut off, and the rest is safe to eat. However, soft or semi-soft aged cheeses with mold should be discarded, as mold can penetrate deeper into the cheese.

Mold is intentionally introduced or allowed to grow in certain aged cheeses, like blue cheese or Brie, as part of their flavor development. Other aged cheeses are aged in controlled environments to prevent mold growth, resulting in a mold-free product.

Yes, aged cheese without mold can still spoil due to factors like improper storage, bacterial growth, or drying out. Always check for off odors, textures, or flavors before consuming.