The question of whether all cheese is considered dairy is a common one, rooted in the fundamental ingredients and production processes of cheese. Cheese is traditionally made from the milk of animals such as cows, goats, or sheep, which categorizes it as a dairy product. However, the rise of plant-based alternatives has introduced non-dairy cheeses made from ingredients like nuts, soy, or coconut, blurring the lines of this classification. While these alternatives mimic the texture and flavor of traditional cheese, they are not derived from animal milk and thus do not fall under the dairy category. This distinction is important for dietary considerations, such as lactose intolerance or veganism, where understanding the source of the product is crucial. Therefore, while most cheese is indeed dairy, not all cheese products can be classified as such.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition of Dairy | Dairy refers to food products made from milk, including products from mammals like cows, goats, and sheep. |

| Cheese Composition | Cheese is made from milk, which is a dairy product, through processes like curdling and aging. |

| Primary Ingredient | Milk (dairy) is the primary ingredient in cheese production. |

| Lactose Content | Most cheeses contain minimal lactose due to the fermentation process, but some fresh cheeses may have higher lactose levels. |

| Dietary Classification | Cheese is universally classified as a dairy product in dietary guidelines and food labeling. |

| Allergens | Cheese contains milk proteins (e.g., casein, whey), which are common dairy allergens. |

| Vegan Alternatives | Vegan cheeses are not considered dairy as they are made from plant-based ingredients like nuts, soy, or coconut. |

| Regulatory Standards | Food regulations (e.g., FDA, EU) classify cheese as a dairy product due to its milk origin. |

| Cultural Perception | Globally, cheese is widely recognized and consumed as a dairy product. |

| Exceptions | There are no exceptions; all cheese made from milk is considered dairy. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cheese Production Process: Involves curdling milk, separating curds, and aging, confirming dairy origin

- Non-Dairy Alternatives: Plant-based cheeses use nuts, soy, or coconut, not dairy milk

- Lactose Content: Most cheese has low lactose, but is still dairy due to milk source

- Dairy Definition: Cheese is dairy as it’s made from milk, a dairy product

- Regulatory Classification: Food standards classify cheese as dairy, despite variations in lactose levels

Cheese Production Process: Involves curdling milk, separating curds, and aging, confirming dairy origin

Cheese, a beloved staple in diets worldwide, is undeniably a dairy product. Its production process begins with milk, the quintessential dairy ingredient, and involves a series of transformations that confirm its dairy origin. The journey from milk to cheese is both an art and a science, requiring precision and patience.

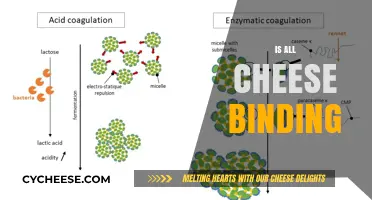

The Curdling Stage: A Chemical Transformation

The first step in cheese production is curdling milk, a process that turns liquid milk into a solid mass. This is achieved by adding a starter culture (bacteria) and rennet (an enzyme), which cause the milk proteins (casein) to coagulate. For example, in cheddar cheese production, mesophilic bacteria are used, while blue cheese often employs penicillium molds. The curdling process typically takes 30–60 minutes, depending on the type of milk and desired cheese variety. This stage is critical, as it sets the foundation for the cheese’s texture and flavor.

Separating Curds and Whey: A Mechanical Precision

Once curdled, the mixture separates into curds (solid milk proteins) and whey (liquid). The curds are then cut into smaller pieces to release more whey, a step that influences the cheese’s final moisture content. For hard cheeses like Parmesan, the curds are heated to 55°C (131°F) and pressed to expel excess whey, resulting in a dense, dry texture. In contrast, soft cheeses like mozzarella retain more moisture, with curds gently stretched and kneaded. This separation process is a delicate balance, as over-cutting or under-heating can alter the cheese’s consistency.

Aging: Where Dairy Becomes Cheese

Aging is where cheese develops its distinct flavor, texture, and character. During this stage, the curds are salted, molded, and stored in controlled environments. For instance, Brie ages for 4–8 weeks at 12°C (54°F), allowing its rind to form and interior to soften. Harder cheeses like Gruyère age for 6–12 months, developing complex nutty flavors. Aging is a dairy-specific process, as it relies on the natural enzymes and bacteria present in milk to break down proteins and fats. Without dairy as the base, this transformation would be impossible.

Practical Tips for Cheese Enthusiasts

Understanding the dairy-centric production process can enhance your appreciation of cheese. When selecting cheese, consider its aging time—younger cheeses are milder, while aged varieties are bolder. For home cheesemaking, start with simple recipes like ricotta, which requires only milk, vinegar, and heat. Always use high-quality dairy for the best results, and experiment with different starter cultures to create unique flavors.

In conclusion, the cheese production process—curdling milk, separating curds, and aging—is a testament to its dairy origin. Each step relies on milk’s inherent properties, making cheese a quintessential dairy product. Whether you’re a connoisseur or a casual consumer, this process highlights the craftsmanship behind every bite.

Should Fresh Cheese Curds Be Refrigerated? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Non-Dairy Alternatives: Plant-based cheeses use nuts, soy, or coconut, not dairy milk

Not all cheese is created equal, especially when it comes to dairy content. While traditional cheese is made from milk, a growing number of plant-based alternatives offer a dairy-free experience. These cheeses, crafted from nuts, soy, or coconut, cater to vegans, lactose intolerant individuals, and those seeking diverse culinary options.

Understanding the distinction between dairy and non-dairy cheese is crucial for informed dietary choices.

Ingredient Breakdown: Plant-based cheeses rely on a variety of bases. Nut-based cheeses, like cashew or almond cheese, offer a creamy texture and mild flavor, often enhanced with nutritional yeast for a cheesy tang. Soy-based cheeses, such as those made from tofu, provide a firmer texture and can mimic the meltability of dairy cheese. Coconut milk-based cheeses offer a rich, creamy mouthfeel and a subtle sweetness, making them ideal for desserts or spreads.

Texture and Flavor: Achieving the right texture and flavor in non-dairy cheese can be challenging. Manufacturers often use fermentation techniques, similar to traditional cheesemaking, to develop complex flavors. Adding ingredients like agar-agar or tapioca starch helps replicate the meltability and stretchiness associated with dairy cheese.

Nutritional Considerations: While plant-based cheeses offer a dairy-free alternative, their nutritional profile varies. Nut-based cheeses are generally higher in healthy fats and protein, while soy-based cheeses provide a complete protein source. Coconut milk-based cheeses tend to be higher in saturated fat. Reading labels is essential to understand the specific nutritional content and choose options that align with individual dietary needs.

Practical Tips: Experimenting with different types of plant-based cheeses is key to finding favorites. Some melt better than others, making them suitable for pizzas or grilled cheese sandwiches. Others excel as spreads or crumbles on salads. Pairing plant-based cheeses with complementary flavors, such as fruits, nuts, or crackers, can enhance their taste and create delicious appetizers or snacks.

The Future of Cheese: The market for plant-based cheeses is rapidly expanding, with continuous innovation in ingredients, textures, and flavors. As consumer demand grows, we can expect even more sophisticated and diverse non-dairy cheese options to emerge, further blurring the lines between traditional and plant-based cheese experiences.

Mastering Roux: The Secret to Creamy Macaroni and Cheese Perfection

You may want to see also

Lactose Content: Most cheese has low lactose, but is still dairy due to milk source

Cheese, a beloved staple in diets worldwide, often sparks confusion regarding its dairy classification, especially for those monitoring lactose intake. While it’s true that most cheese contains minimal lactose, its dairy status remains undeniable due to its milk-based origin. This distinction is crucial for individuals with lactose intolerance or dairy allergies, as even trace amounts of milk proteins can trigger reactions. Understanding the lactose content in cheese allows for informed dietary choices without sacrificing flavor or nutrition.

Analyzing lactose levels reveals why many cheeses are tolerable for lactose-sensitive individuals. During the cheesemaking process, lactose is largely removed as milk sugars are converted into lactic acid. For instance, hard cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan typically contain less than 1 gram of lactose per ounce, making them suitable for low-lactose diets. In contrast, softer, fresher cheeses like mozzarella or cream cheese retain slightly more lactose, though still in modest amounts (around 1-3 grams per ounce). These variations highlight the importance of selecting cheeses based on individual tolerance thresholds.

For those navigating lactose intolerance, practical strategies can maximize cheese enjoyment while minimizing discomfort. Pairing cheese with lactase enzymes or opting for aged varieties like Swiss or Gruyère can further reduce lactose impact. Additionally, portion control is key; starting with small servings and gradually increasing intake allows the body to adapt. Children and older adults, who may have varying degrees of lactose intolerance, should consult healthcare providers for personalized guidance on incorporating cheese into their diets.

Comparatively, while plant-based alternatives like vegan cheese avoid dairy entirely, they lack the nutritional profile of traditional cheese, which includes calcium, protein, and vitamins like B12. For those who can tolerate low-lactose dairy, cheese remains a superior option for both taste and health benefits. Ultimately, recognizing that cheese’s dairy classification stems from its milk source, not its lactose content, empowers individuals to make choices aligned with their dietary needs and preferences.

Pairing Perfection: Elevating Your Wine Experience with the Right Cheese

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$1.67

Dairy Definition: Cheese is dairy as it’s made from milk, a dairy product

Cheese is undeniably a dairy product, as its primary ingredient is milk, which is the cornerstone of all dairy. The process of making cheese involves curdling milk, typically from cows, goats, sheep, or buffalo, and separating the solids (curds) from the liquid (whey). This fundamental connection to milk categorizes cheese firmly within the dairy family. Understanding this definition is crucial for dietary choices, especially for those with lactose intolerance or dairy allergies, as even small amounts of milk-derived products can trigger symptoms. For instance, hard cheeses like cheddar contain lower lactose levels compared to soft cheeses like ricotta, but they still originate from milk and are thus considered dairy.

From a nutritional standpoint, cheese inherits many of milk’s characteristics, including its protein, calcium, and fat content. A single ounce of cheddar cheese, for example, provides about 7 grams of protein and 20% of the daily recommended calcium intake for adults. However, it also contains approximately 9 grams of fat, including saturated fat, which should be consumed in moderation. This duality highlights why cheese is both a valuable dairy product and one that requires mindful consumption. For children aged 2–3, the American Heart Association recommends limiting daily saturated fat intake to 7 grams, making portion control essential when serving cheese as part of a balanced diet.

The classification of cheese as dairy also has implications for food labeling and dietary restrictions. In many countries, including the United States, food products must clearly indicate the presence of dairy to comply with allergen labeling laws. For individuals following vegan diets, this classification is non-negotiable: cheese made from animal milk is excluded, though plant-based alternatives like cashew or almond cheese are available. However, these alternatives are not considered dairy, as they do not contain milk. This distinction underscores the importance of understanding the dairy definition when navigating dietary choices or restrictions.

Practically speaking, knowing that cheese is dairy allows for informed substitutions and culinary creativity. For those avoiding dairy, options like nutritional yeast or dairy-free cheese can mimic the umami flavor of cheese in recipes. Conversely, for those embracing dairy, experimenting with different cheeses—from creamy brie to sharp parmesan—can elevate dishes. A tip for reducing dairy intake without eliminating cheese entirely is to use stronger-flavored varieties in smaller quantities. For example, a tablespoon of grated parmesan can provide the same flavor impact as a larger portion of milder cheese, allowing for enjoyment without excessive dairy consumption.

In conclusion, the dairy definition of cheese as a milk-derived product is both scientifically accurate and practically significant. Whether for health, dietary, or culinary reasons, recognizing this classification empowers individuals to make informed choices. From nutritional benefits to allergen awareness, the dairy status of cheese is a key factor in its role in diets worldwide. By understanding this relationship, one can navigate the complexities of dairy consumption with clarity and confidence.

Converting 30 Grams of Cheese to Tablespoons: A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Regulatory Classification: Food standards classify cheese as dairy, despite variations in lactose levels

Cheese, in the eyes of food regulators, is unequivocally dairy. This classification is rooted in the Codex Alimentarius, the international food standards established by the FAO and WHO, which defines cheese as a product derived from milk. Despite the lactose content varying widely—from nearly undetectable levels in aged cheeses like Parmesan to higher amounts in fresh cheeses like mozzarella—regulatory bodies prioritize the source material (milk) over the final lactose concentration. This means that even lactose-intolerant individuals, who might tolerate aged cheeses, must still recognize cheese as a dairy product due to its regulatory categorization.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this classification is crucial for labeling and dietary compliance. For instance, in the United States, the FDA mandates that products labeled as "cheese" must meet specific milk-derived criteria, ensuring consistency for consumers. However, this classification can create confusion for those with dairy allergies or intolerances. While aged cheeses may contain minimal lactose (often less than 0.1 grams per serving), they still pose risks for individuals with milk protein allergies. Thus, regulatory standards serve as a reminder that cheese’s dairy status is non-negotiable, regardless of its lactose levels.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between regulatory and nutritional perspectives. Nutritionally, cheese is often grouped based on its lactose content, with hard cheeses considered low-lactose alternatives. Yet, regulatory frameworks ignore this nuance, focusing instead on the dairy origin. This discrepancy underscores the importance of reading labels carefully. For example, a lactose-intolerant person might safely consume 30 grams of aged cheddar daily but should avoid assuming all "dairy-free" claims apply to cheese. Regulatory classification ensures transparency but requires consumer awareness to navigate dietary restrictions effectively.

Persuasively, this classification also influences industry practices and consumer trust. By strictly defining cheese as dairy, regulators prevent mislabeling and protect public health. However, it also limits innovation in dairy-free cheese alternatives, which often struggle to meet traditional cheese standards. For instance, plant-based cheeses cannot legally use the term "cheese" in some regions, despite mimicking its texture and flavor. This regulatory rigidity highlights the tension between tradition and evolving dietary needs, urging stakeholders to balance compliance with consumer education.

In conclusion, the regulatory classification of cheese as dairy, irrespective of lactose levels, serves as a cornerstone for food safety and labeling consistency. It empowers consumers to make informed choices while ensuring products meet established standards. However, it also demands a nuanced understanding of how lactose content varies across cheese types. By recognizing this classification, individuals can better navigate dietary restrictions, while industries can innovate within regulatory boundaries. Cheese may be dairy by definition, but its diversity requires a closer look beyond the label.

Are Kraft Singles Real Cheese? Unwrapping the Truth Behind the Slice

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, all cheese is considered dairy because it is made from milk, which is a dairy product.

Not all cheeses are equally problematic for lactose-intolerant individuals. Hard cheeses like cheddar or Swiss have lower lactose content compared to soft cheeses like ricotta or cream cheese.

Yes, there are non-dairy cheese alternatives made from plant-based ingredients like nuts, soy, or coconut, which are suitable for vegan or dairy-free diets.

Yes, cheese made from goat or sheep milk is still considered dairy because it is produced from animal milk, regardless of the animal source.