Cheese is a beloved dairy product enjoyed worldwide, but its production process often raises questions, particularly about its relationship to mold. While it’s true that some cheeses, like blue cheese or Brie, contain visible mold as part of their flavor and texture profile, not all cheese is made by intentionally introducing mold to milk. In fact, most cheeses are created through the coagulation of milk using rennet or bacterial cultures, followed by draining and pressing, without any mold involvement. Mold in cheese is a specific and controlled process, and its presence is not universal across all varieties. Thus, the statement all cheese is mold milk is a misconception, as the role of mold is limited to certain types of cheese and is not a defining characteristic of cheese production as a whole.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Not all cheese is made from mold, but some cheeses use mold in their production process. |

| Mold in Cheese | Mold is intentionally added to certain cheeses (e.g., blue cheese, Brie, Camembert) to create flavor, texture, and appearance. |

| Non-Mold Cheeses | Many cheeses (e.g., cheddar, mozzarella, Swiss) are made without mold and rely on bacterial cultures for fermentation. |

| Milk Source | All cheese is made from milk (cow, goat, sheep, or other animals), but not all milk is turned into mold-containing cheese. |

| Fermentation | Cheese production involves fermentation, which can be achieved with bacteria, mold, or both, depending on the type. |

| Safety | Mold in cheese is generally safe when intentionally added during production, but mold on aged cheese should be avoided if not part of the process. |

| Texture/Flavor | Mold-containing cheeses often have distinct textures (e.g., veins in blue cheese) and flavors compared to non-mold cheeses. |

| Examples | Mold cheeses: Blue cheese, Brie, Camembert. Non-mold cheeses: Cheddar, Parmesan, Feta. |

| Production Time | Mold-containing cheeses often require longer aging periods compared to non-mold cheeses. |

| Health Benefits | Both mold and non-mold cheeses can provide nutritional benefits, including protein, calcium, and probiotics. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Natural Cheese Molding Process

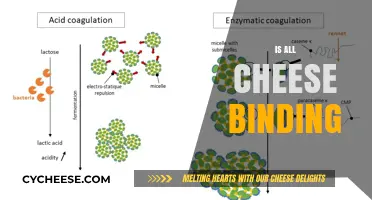

Cheese production is a delicate dance between milk, bacteria, and time, and the natural molding process is a crucial step in crafting certain varieties. This process, often associated with artisanal and traditional cheese-making, involves the intentional introduction of specific molds to transform milk into a flavorful, textured delight.

The Science Behind Molding:

Imagine a microscopic world where Penicillium camemberti and Penicillium candidum are the stars. These molds, when introduced to the cheese's surface, begin a slow and controlled digestion of the curd. The process is a delicate balance; the molds break down proteins and fats, creating the distinctive flavors and textures we associate with cheeses like Camembert and Brie. The mold's enzymes act as tiny chefs, tenderizing the cheese and developing its characteristic creamy interior and bloomy rind.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Natural Molding:

- Inoculation: After the initial curdling and draining of the milk, the cheese is ready for its mold bath. This step involves spraying or dipping the cheese in a solution containing the desired mold spores. The dosage is critical; typically, a concentration of 10^6 to 10^8 spores per milliliter is used, ensuring a healthy mold growth without overwhelming the cheese.

- Incubation: The cheese is then placed in a controlled environment, often a temperature- and humidity-regulated room. Here, the magic happens. Over several days to weeks, the molds colonize the cheese's surface, gradually working their way in. The ideal temperature for this process is around 12-15°C, encouraging slow, even growth.

- Aging and Ripening: As the molds mature, the cheese is regularly turned and monitored. This stage is an art, as the cheesemaker decides when the mold has done its job, achieving the desired flavor and texture. The cheese may be aged for weeks or even months, with regular inspections to ensure the mold remains beneficial and doesn't spoil the batch.

Cautions and Considerations:

Natural molding is a traditional method, but it requires precision. Modern cheesemakers often use specific mold cultures, ensuring consistency and safety. Wild molds, while natural, can be unpredictable, leading to off-flavors or even harmful bacteria. Therefore, controlled environments and specific mold strains are preferred. Additionally, this process is not suitable for all cheeses; harder varieties like Cheddar or Parmesan undergo different aging processes, often involving bacteria rather than molds.

In the world of cheese, the natural molding process is a testament to the beauty of controlled decay, where science and art intertwine to create culinary masterpieces. It's a reminder that sometimes, a little mold can go a long way in crafting the perfect bite.

Is Government Cheese Still a Thing in the US Today?

You may want to see also

Types of Mold in Cheese

Not all cheese is made from mold, but many beloved varieties owe their distinctive flavors and textures to specific mold cultures. These molds are carefully selected and introduced during the cheesemaking process, transforming humble milk into complex, aged delights. Understanding the types of mold used in cheese production reveals the artistry behind these culinary treasures.

Here’s a breakdown of key mold players:

Penicillium camemberti and Penicillium candidum: These cousins are the stars of soft-ripened cheeses like Camembert and Brie. Penicillium camemberti creates the iconic white, velvety rind and contributes a mild, earthy flavor. Penicillium candidum, often used in triple crème cheeses, results in a thinner, smoother rind and a richer, buttery taste. Both molds thrive in high-moisture environments, breaking down the cheese’s interior as they grow, yielding a creamy, spreadable texture.

Penicillium roqueforti: This mold is the backbone of blue cheeses such as Roquefort, Gorgonzola, and Stilton. It produces veins of blue or green mold throughout the cheese, imparting a pungent, spicy flavor and a crumbly texture. Penicillium roqueforti requires oxygen to grow, which is why blue cheeses are pierced during aging to allow air penetration. The intensity of flavor depends on aging time, with longer maturation resulting in sharper, more assertive notes.

Geotrichum candidum: Found in cheeses like Saint-Marcellin and Mont d’Or, this mold forms a thin, wrinkled, edible rind with a yeasty, slightly nutty aroma. Geotrichum candidum works in tandem with bacteria to create a soft, gooey interior. Unlike Penicillium molds, it prefers lower temperatures, making it ideal for cold-aging processes.

Brevibacterium linens: Responsible for the orange-hued rinds of washed-rind cheeses like Époisses and Limburger, this bacteria (often misclassified as a mold) produces a strong, pungent odor reminiscent of sweaty socks. Despite its off-putting smell, Brevibacterium linens contributes a surprisingly mild, savory flavor to the cheese beneath the rind. Regular washing with brine or alcohol during aging encourages its growth, intensifying both color and aroma.

Selecting the right mold is crucial for achieving the desired flavor, texture, and appearance in cheese. Each mold variety interacts uniquely with milk, bacteria, and aging conditions, creating a symphony of sensory experiences. For home cheesemakers, using high-quality mold cultures and maintaining precise temperature and humidity controls are essential for success. Experimenting with different molds can unlock a world of artisanal possibilities, proving that not all cheese relies on mold, but when it does, the results are nothing short of magical.

Quarter Pounder with Cheese in Amsterdam: Its Local Name Explained

You may want to see also

Health Risks of Moldy Cheese

Moldy cheese isn’t inherently dangerous, but it’s a gamble with your health. While some cheeses, like blue cheese, rely on specific molds for flavor, others can develop harmful strains when spoiled. The key difference lies in the type of mold and the cheese’s moisture content. Soft cheeses with high moisture, such as Brie or Camembert, are more likely to harbor dangerous molds like *Listeria* or *Salmonella* when they spoil. Hard cheeses, like cheddar, are less risky because their lower moisture content inhibits mold penetration—simply cut off the moldy part (with an inch of buffer) and consume the rest safely.

The health risks of consuming moldy cheese vary by individual. Immunocompromised individuals, pregnant women, and young children are particularly vulnerable to mold toxins, which can cause allergic reactions, respiratory issues, or severe infections. For example, *Aspergillus* molds in spoiled cheese can produce aflatoxins, known carcinogens even in small doses. Symptoms of mold exposure range from mild (nausea, vomiting) to severe (organ damage, neurological issues). If you suspect contamination, err on the side of caution—discard soft cheeses entirely and inspect hard cheeses thoroughly before consumption.

Not all molds are created equal, and some are downright deceptive. White, fuzzy mold on soft cheese might seem harmless but could indicate deeper contamination. Blue or green molds on hard cheeses are often surface-level and less concerning, but always inspect for texture changes or off odors. A practical tip: store cheese properly (wrapped in wax or parchment paper, not plastic) to slow mold growth. If you’re unsure, remember this rule: when in doubt, throw it out.

To minimize risks, adopt a proactive approach to cheese storage and consumption. Keep cheese refrigerated at or below 40°F (4°C) and consume it by the “best by” date. For leftovers, rewrap in fresh paper and avoid cross-contamination with utensils. Educate yourself on the appearance of safe molds (like those in blue cheese) versus harmful ones. While moldy cheese isn’t always toxic, the potential health risks far outweigh the convenience of salvaging a spoiled product. Play it safe—your gut will thank you.

Mince and Cheese Pie: What Would Americans Call This Dish?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Difference Between Mold and Spoilage

Mold and spoilage are often conflated, but they represent distinct processes with different implications for food safety and quality. Mold is a type of fungus that grows on food surfaces, visible as fuzzy patches of green, blue, white, or black. It thrives in moist, organic environments and can produce mycotoxins, which are harmful if ingested. Spoilage, on the other hand, is a broader term encompassing any deterioration in food quality—texture, flavor, or appearance—caused by bacteria, yeast, or chemical reactions, often without visible mold. Understanding this difference is crucial when assessing whether a food item, like cheese, is safe to consume.

Consider the example of hard cheeses, such as cheddar or Parmesan. If mold appears on these, it’s generally safe to cut off the affected area plus an additional inch around it, as the dense structure prevents mold from penetrating deeply. However, soft cheeses like Brie or Camembert should be discarded if moldy, as their high moisture content allows mold to spread throughout. This distinction highlights how mold’s impact varies by food type, whereas spoilage—such as a sour smell or slimy texture—typically renders any cheese unsafe, regardless of hardness.

From a practical standpoint, preventing mold and spoilage involves controlling environmental factors. Store cheese in the refrigerator at 35–40°F (2–4°C) and wrap it in wax or parchment paper to allow breathability while minimizing moisture buildup. Avoid plastic wrap, which traps humidity and accelerates mold growth. For longer storage, hard cheeses can be frozen, though this may alter their texture. Regularly inspect cheese for signs of spoilage, such as off-odors or discoloration, and trust your senses—if it smells or looks wrong, discard it.

Persuasively, recognizing the difference between mold and spoilage empowers consumers to reduce food waste. While mold on certain foods can be managed, spoilage is irreversible. For instance, a slight mold patch on a block of cheddar doesn’t necessitate throwing it all away, but a rancid smell indicates spoilage, requiring disposal. This knowledge not only saves money but also promotes sustainability by minimizing unnecessary waste.

In conclusion, mold and spoilage are distinct phenomena requiring different responses. Mold is a visible fungus that may be manageable in certain foods, while spoilage is a broader degradation often signaled by sensory changes. By understanding these differences and implementing proper storage practices, consumers can safely enjoy foods like cheese while minimizing waste. Always prioritize safety—when in doubt, throw it out.

Mastering the Art of Drying Cheese: Tips for Perfect Preservation

You may want to see also

Cheese Varieties Made with Mold

Not all cheese is made with mold, but many beloved varieties owe their distinctive flavors and textures to the deliberate introduction of specific molds. This process, known as mold ripening, transforms ordinary milk into complex, nuanced cheeses. For instance, the veins in blue cheese like Roquefort or Gorgonzola are the result of *Penicillium roqueforti*, a mold that breaks down fats and proteins, releasing pungent, earthy compounds. Similarly, the velvety rind of Brie and Camembert develops from *Penicillium camemberti*, which contributes a creamy interior and a slightly mushroomy aroma. These molds are not only safe but essential, acting as both preservative and flavor enhancer.

To understand how mold-ripened cheeses are made, consider the steps involved. After curdling milk with rennet or acid, the cheese is inoculated with specific mold cultures. For blue cheeses, spores are mixed directly into the curd or injected into the aging cheese, creating the characteristic veins. Soft-ripened cheeses like Brie are surface-ripened, where molds grow on the exterior, softening the interior as they mature. Humidity and temperature control are critical during aging—blue cheeses typically age for 2–4 months at around 50°F (10°C), while Brie matures for 4–6 weeks at slightly warmer temperatures. Home cheesemakers can experiment with mold-ripened varieties using store-bought cultures, but precision in environment and timing is key to avoiding spoilage.

From a health perspective, the molds in cheese are not only safe but beneficial in moderation. Unlike harmful molds that grow on spoiled food, cheese molds are carefully selected and controlled. For example, *Penicillium roqueforti* produces roquefortine C, a compound with antimicrobial properties that inhibits unwanted bacteria. However, individuals with mold allergies or compromised immune systems should consume mold-ripened cheeses sparingly, as they may trigger reactions. Pregnant women are often advised to avoid soft-ripened cheeses due to the slight risk of *Listeria*, though pasteurized milk versions are safer. Always store mold-ripened cheeses properly—wrap them in wax or parchment paper, not plastic, to allow them to breathe.

Comparing mold-ripened cheeses highlights their diversity. Blue cheeses like Stilton are bold and salty, ideal for pairing with sweet fruits or rich meats. Soft-ripened cheeses like Camembert offer a milder, buttery profile, perfect for spreading on crusty bread or melting into dishes. Washed-rind cheeses, such as Époisses, also use molds (often *B. linens*) but combine them with bacteria for a sticky rind and intense aroma. Each style showcases how mold interacts with milk, aging, and other microorganisms to create unique sensory experiences. For a practical tip, serve mold-ripened cheeses at room temperature to fully appreciate their flavors and textures.

In conclusion, mold-ripened cheeses are a testament to the art of fermentation, where controlled spoilage becomes culinary mastery. Whether you’re savoring the crumbly bite of a blue cheese or the oozy center of a Camembert, these varieties remind us that mold is not always an enemy but a collaborator in crafting food’s most complex delights. By understanding the science and techniques behind these cheeses, even casual enthusiasts can deepen their appreciation and confidently explore this flavorful category.

Meet the Talented Members of Richard Cheese: Names and Roles

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all cheese is made from mold milk. While some cheeses, like blue cheese, intentionally use mold cultures during production, most cheeses are made by curdling milk with bacteria or rennet, not mold.

No, not all cheese contains mold. Many cheeses, such as mozzarella or cheddar, are made without mold. Mold is only present in specific types of cheese where it is added intentionally for flavor or texture.

No, the mold used in cheese production is different from the mold that grows on spoiled milk. Cheese molds are specific strains cultivated for safe consumption, while mold on milk is typically a sign of spoilage and should be avoided.