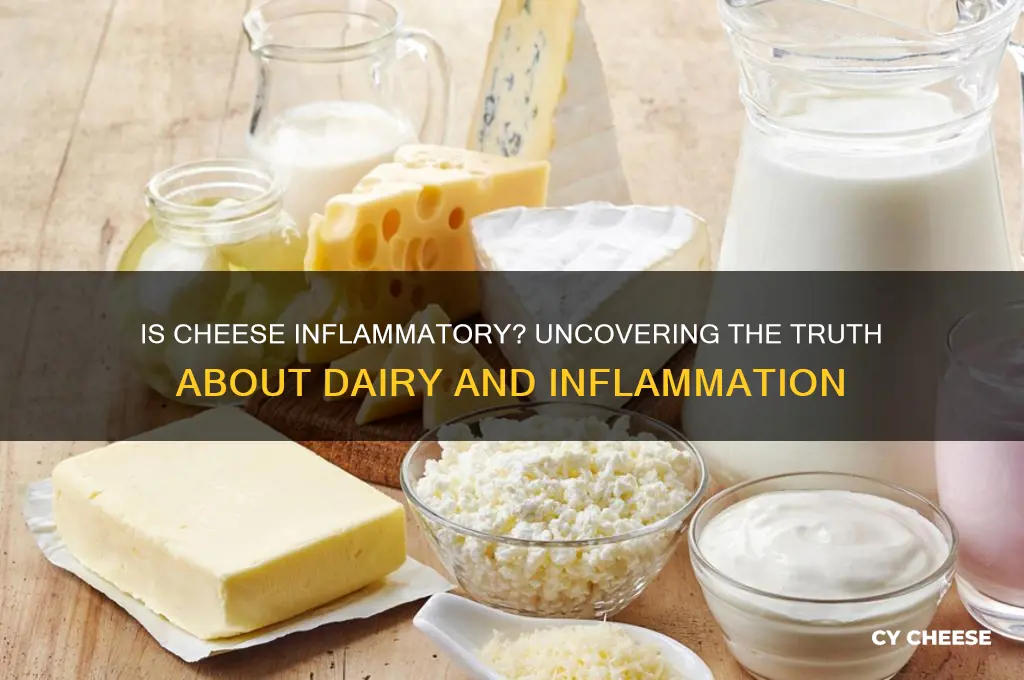

Cheese, a beloved staple in many diets worldwide, has long been a subject of debate in the realm of nutrition, particularly concerning its potential inflammatory effects. While some studies suggest that certain types of cheese, especially those high in saturated fats, may contribute to inflammation in the body, others highlight its rich content of nutrients like calcium, protein, and probiotics, which can have anti-inflammatory benefits. The variability in cheese types, from aged cheddar to fresh mozzarella, further complicates the discussion, as different varieties may have distinct impacts on health. Understanding whether cheese is an inflammatory food requires examining individual dietary habits, overall health conditions, and the specific characteristics of the cheese consumed.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cheese and Inflammation Link: Research suggests some cheeses may trigger inflammation due to saturated fats

- Types of Cheese: Hard cheeses like cheddar are more inflammatory than soft cheeses like mozzarella

- Individual Tolerance: Dairy sensitivity varies; some people experience inflammation, while others do not

- Processed vs. Natural: Processed cheeses often contain additives that can increase inflammatory responses

- Moderation and Alternatives: Consuming cheese in moderation or opting for anti-inflammatory alternatives like goat cheese helps

Cheese and Inflammation Link: Research suggests some cheeses may trigger inflammation due to saturated fats

Cheese, a staple in many diets worldwide, has recently come under scrutiny for its potential role in inflammation. Research indicates that certain types of cheese, particularly those high in saturated fats, may trigger inflammatory responses in the body. This is largely due to the presence of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and saturated fatty acids, which are known to stimulate pro-inflammatory pathways. For instance, a study published in the *Journal of Nutrition* found that high consumption of full-fat dairy products, including cheddar and cream cheese, was associated with elevated markers of inflammation in adults over 40. This suggests that while cheese can be a source of essential nutrients like calcium and protein, its impact on inflammation warrants careful consideration.

To mitigate the inflammatory potential of cheese, it’s instructive to focus on moderation and mindful selection. Opting for cheeses with lower saturated fat content, such as fresh mozzarella, feta, or part-skim ricotta, can be a practical strategy. These varieties typically contain fewer AGEs and saturated fats compared to aged or processed cheeses like cheddar or blue cheese. Additionally, pairing cheese with anti-inflammatory foods, such as leafy greens, berries, or nuts, can help balance its effects. For example, a small serving of goat cheese crumbled over a spinach salad with strawberries and walnuts combines the pleasure of cheese with ingredients known to reduce inflammation.

A comparative analysis of cheese types reveals that not all cheeses are created equal in terms of their inflammatory impact. Hard, aged cheeses like Parmesan or Gruyère tend to have higher levels of AGEs due to their prolonged processing and higher fat content. In contrast, softer, fresher cheeses like cottage cheese or fresh chèvre have lower AGE levels and are less likely to provoke inflammation. A study in *Food & Function* highlighted that fermented cheeses, such as Gouda or Swiss, may have a milder inflammatory effect due to their probiotic content, which can support gut health and modulate immune responses. This underscores the importance of choosing cheese varieties strategically based on individual health goals.

Persuasively, it’s worth noting that eliminating cheese entirely may not be necessary for everyone. For those without specific health conditions like lactose intolerance or dairy sensitivities, moderate consumption of low-inflammatory cheese options can still fit into a balanced diet. However, individuals with chronic inflammatory conditions, such as arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease, may benefit from reducing or avoiding high-fat cheeses altogether. Consulting a dietitian or healthcare provider can provide personalized guidance, ensuring that cheese consumption aligns with overall health objectives. By making informed choices, cheese lovers can enjoy their favorite dairy product while minimizing its potential inflammatory effects.

McDonald's Cheese Sticks: Are They on the Menu? Find Out!

You may want to see also

Types of Cheese: Hard cheeses like cheddar are more inflammatory than soft cheeses like mozzarella

Cheese, a staple in many diets, varies widely in its inflammatory potential, with hard cheeses like cheddar often triggering more inflammation than softer varieties like mozzarella. This distinction arises from differences in processing, fat content, and protein structures. Hard cheeses undergo longer aging processes, which increase their concentration of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and saturated fats—both linked to inflammatory responses in the body. For instance, a 30-gram serving of cheddar contains approximately 6 grams of fat, primarily saturated, compared to mozzarella’s 4 grams in the same portion. These factors make hard cheeses more likely to exacerbate conditions like arthritis or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in sensitive individuals.

To minimize inflammation, consider swapping hard cheeses for softer alternatives in your diet. Mozzarella, ricotta, and feta are excellent choices due to their lower fat content and shorter aging periods. For example, incorporating mozzarella into salads or using ricotta in place of cheddar in recipes can reduce inflammatory triggers without sacrificing flavor. Additionally, portion control is key; limiting intake to 1–2 servings per day can help manage potential inflammatory effects. Pairing cheese with anti-inflammatory foods like leafy greens, berries, or nuts can further offset its impact.

From a comparative standpoint, the inflammatory potential of cheese is not just about hardness but also lactose and protein content. Hard cheeses are typically lower in lactose, which might benefit those with lactose intolerance, but their higher protein density can still provoke inflammation in some. Soft cheeses, while often higher in lactose, have a milder effect due to their lower overall fat and protein concentrations. For instance, individuals with lactose sensitivity might tolerate small amounts of soft cheese better than hard varieties. Understanding these nuances allows for more informed dietary choices tailored to individual tolerance levels.

Practical tips for navigating cheese consumption include reading labels to identify fat and protein content, opting for organic or grass-fed varieties that may have a more favorable fatty acid profile, and experimenting with fermented cheeses like Gouda or Swiss, which contain probiotics that can support gut health. For those with chronic inflammatory conditions, consulting a dietitian to create a personalized plan is advisable. By focusing on softer, lower-fat cheeses and mindful portioning, cheese can remain a part of a balanced diet without significantly contributing to inflammation.

Ignore the Cheese Guru: Why His Advice Isn't Worth Following

You may want to see also

Individual Tolerance: Dairy sensitivity varies; some people experience inflammation, while others do not

Cheese, a staple in many diets, triggers inflammation in some individuals but not in others. This disparity highlights the concept of individual tolerance, a critical factor in understanding how dairy affects the body. While some people can enjoy a variety of cheeses without issue, others may experience bloating, joint pain, or skin irritation after consumption. This variation is influenced by genetics, gut health, and overall immune function, making it essential to approach dairy consumption with personalized awareness.

To determine your tolerance, start with a simple elimination diet. Remove all dairy products, including cheese, for 3–4 weeks. Monitor symptoms during this period, noting any changes in digestion, energy levels, or inflammation markers. Gradually reintroduce small portions of cheese (1–2 ounces) and observe your body’s response over 24–48 hours. If symptoms reappear, consider reducing or eliminating cheese from your diet. For those with mild sensitivity, fermented cheeses like cheddar or Swiss may be better tolerated due to their lower lactose content.

Age and health status play a role in dairy tolerance. Younger individuals with robust digestive enzymes often process dairy more efficiently, while older adults may experience decreased lactase production, leading to intolerance. Pregnant or breastfeeding women should consult a healthcare provider before making dietary changes, as calcium from dairy can be beneficial. Additionally, individuals with conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or autoimmune disorders may be more prone to inflammation from cheese and should proceed cautiously.

Practical tips can help manage dairy sensitivity. Opt for lactose-free or low-lactose cheeses if lactose is the culprit. Pair cheese with digestive enzymes containing lactase to aid breakdown. Experiment with smaller, infrequent servings to gauge your threshold. For example, a weekly 1-ounce portion of hard cheese might be manageable, while daily consumption could trigger symptoms. Keeping a food diary can help identify patterns and pinpoint specific triggers within dairy products.

Ultimately, individual tolerance to cheese as an inflammatory food is highly personal and requires self-awareness. While some thrive on dairy, others must limit or avoid it to prevent discomfort. By testing your body’s response systematically and adjusting intake accordingly, you can enjoy cheese without compromising health—or discover alternatives that suit your unique needs. This tailored approach ensures that dietary choices align with your body’s specific requirements.

Are Chili Cheese Fries Vegetarian? Uncovering the Truth Behind the Dish

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Processed vs. Natural: Processed cheeses often contain additives that can increase inflammatory responses

Cheese, a beloved staple in many diets, isn’t inherently inflammatory, but the distinction between processed and natural varieties can significantly impact its effects on the body. Processed cheeses, such as American singles or pre-shredded blends, often contain additives like emulsifiers (e.g., sodium phosphate), preservatives (e.g., sorbic acid), and artificial flavors to enhance texture and shelf life. These additives, while convenient, have been linked to increased inflammatory responses in some individuals. For example, a 2018 study published in *Nature* found that emulsifiers can disrupt gut microbiota, potentially triggering low-grade inflammation. If you’re monitoring inflammation, scrutinizing ingredient labels is a practical first step.

Consider this scenario: A 40-year-old with joint pain switches from processed cheese slices to natural cheddar. Within weeks, they notice reduced stiffness. This isn’t anecdotal magic—it’s science. Natural cheeses, like cheddar, Gouda, or mozzarella, are minimally processed and free from additives. Their fermentation process produces bioactive peptides that may even have anti-inflammatory properties, according to a 2014 study in *Food & Function*. The takeaway? Prioritize whole, additive-free cheeses to minimize inflammation risk.

For those who can’t part with processed cheese entirely, moderation is key. Limit intake to 1–2 servings per week, and pair it with anti-inflammatory foods like leafy greens or berries to offset potential effects. Alternatively, opt for processed cheeses labeled "no additives" or "clean ingredients," though these are rarer. A practical tip: Grate your own natural cheese for recipes instead of using pre-shredded versions, which often contain anti-caking agents like cellulose or potato starch.

The age factor also plays a role. Older adults, whose immune systems may be more reactive to dietary triggers, could benefit more from this switch. A 2020 study in *The Journal of Nutrition* suggested that reducing processed food intake in individuals over 50 correlated with lower inflammatory markers. For younger, healthier individuals, the impact may be subtler, but the principle remains: natural cheeses are the safer bet for inflammation-conscious diets.

In conclusion, the processed vs. natural cheese debate isn’t about eliminating cheese but making informed choices. By favoring natural varieties and minimizing additives, you can enjoy cheese without exacerbating inflammation. Small swaps, like choosing a block of Swiss over a pack of processed slices, can yield noticeable health benefits over time. Your gut—and joints—will thank you.

Discover the Creamy White Cheese Used in Classic Lasagna Recipes

You may want to see also

Moderation and Alternatives: Consuming cheese in moderation or opting for anti-inflammatory alternatives like goat cheese helps

Cheese, a staple in many diets, often raises concerns about its inflammatory potential. While some types of cheese can trigger inflammation, especially in sensitive individuals, the key lies in moderation and mindful selection. Consuming cheese in limited quantities—think a 1-ounce serving (about the size of your thumb) per day—can help minimize its inflammatory impact. This approach allows you to enjoy its flavor and nutritional benefits without overloading your system with potentially irritating compounds like saturated fats or lactose.

For those seeking a more proactive strategy, opting for anti-inflammatory alternatives like goat cheese can be a game-changer. Goat cheese, for instance, is easier to digest due to its lower lactose content and different protein structure, making it less likely to provoke inflammation. Similarly, sheep’s milk cheese or aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan contain lower levels of lactose, reducing the risk of digestive discomfort. Incorporating these alternatives into your diet—such as using goat cheese in salads or aged cheeses as a garnish—can provide variety while supporting a less inflammatory response.

Practical tips can further enhance your cheese consumption habits. Pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or fresh vegetables can slow digestion and mitigate potential inflammatory effects. Additionally, paying attention to your body’s response is crucial; if you notice bloating, joint pain, or skin issues after eating certain cheeses, consider reducing your intake or switching to alternatives. For individuals with specific health conditions like arthritis or irritable bowel syndrome, consulting a dietitian can provide personalized guidance on cheese consumption.

Comparatively, while cow’s milk cheese is often the default choice, exploring diverse options like buffalo mozzarella or almond-based vegan cheeses can offer both flavor and health benefits. Vegan cheeses, made from nuts or soy, are naturally lactose-free and often fortified with nutrients, making them an excellent anti-inflammatory choice. However, it’s essential to read labels carefully, as some processed vegan cheeses may contain additives that counteract their benefits. By balancing traditional cheeses with these alternatives, you can create a diet that satisfies your taste buds while promoting overall well-being.

In conclusion, cheese doesn’t have to be off-limits for those concerned about inflammation. By practicing moderation, choosing anti-inflammatory varieties, and incorporating mindful eating habits, you can enjoy cheese as part of a balanced diet. Whether it’s a sprinkle of aged Parmesan on pasta or a dollop of goat cheese on a salad, small adjustments can make a significant difference in managing inflammation and supporting your health.

Should You Refrigerate Cheese Bread? The Surprising Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese can be inflammatory for some people, particularly those sensitive to dairy or lactose intolerant. However, its impact varies depending on the type of cheese and individual tolerance.

Processed cheeses and those high in saturated fats, like cheddar or American cheese, are more likely to trigger inflammation compared to harder, aged cheeses like Parmesan or Swiss.

For some individuals, even without dairy sensitivities, cheese may contribute to inflammation due to its high saturated fat content or the presence of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) formed during aging or heating.

Some cheeses, like goat cheese or feta, may be less inflammatory due to their lower lactose content or healthier fat profiles. Fermented cheeses like Gouda or blue cheese may also have probiotic benefits that reduce inflammation.

Opt for moderate portions of low-lactose, aged, or fermented cheeses, and pair them with anti-inflammatory foods like vegetables or fruits. Monitor your body’s response to identify which cheeses work best for you.