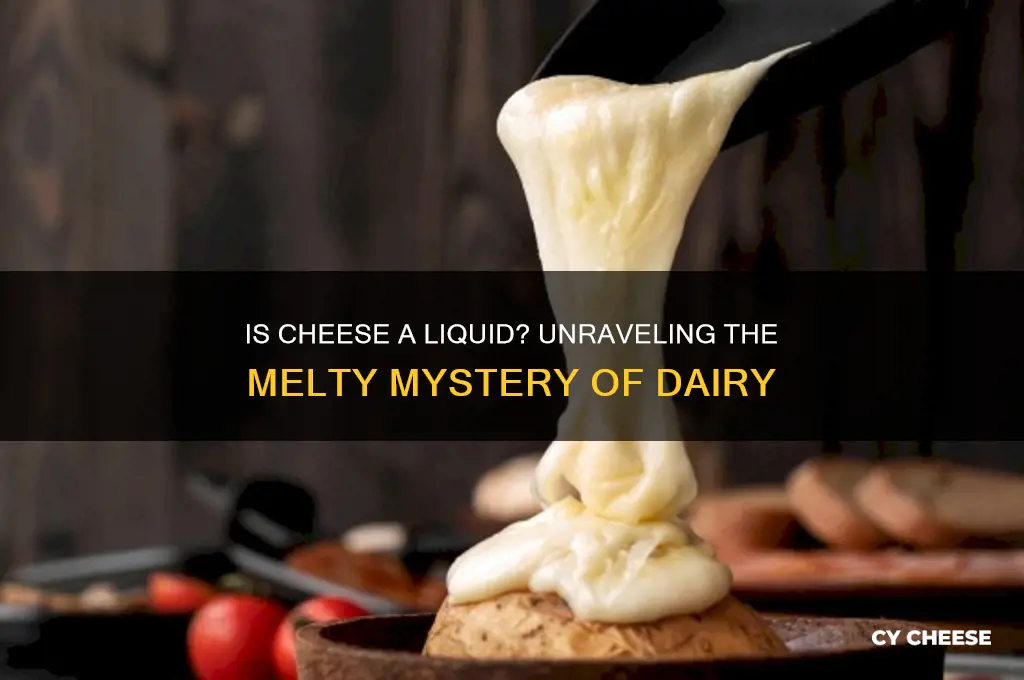

The question of whether cheese is a liquid may seem absurd at first glance, but it delves into fascinating discussions about the nature of matter and the definitions of physical states. Cheese, a beloved dairy product, typically appears solid, yet its behavior under certain conditions—such as melting or oozing—blurs the lines between solid and liquid. This ambiguity has sparked debates in scientific, culinary, and even legal contexts, challenging conventional classifications and inviting a deeper exploration of how we categorize the substances around us.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| State at Room Temperature | Solid |

| Ability to Flow | Limited (soft cheeses can deform under pressure) |

| Molecular Structure | Solid matrix with dispersed fat and protein |

| Scientific Classification | Solid food (not classified as a liquid in physics or chemistry) |

| Legal Classification (e.g., U.S. Customs) | Solid for tariff purposes |

| Melting Behavior | Becomes viscous when heated, but retains some structure |

| Shape Retention | Maintains shape unless acted upon by external force |

| Surface Tension | Not applicable (characteristic of liquids) |

| Compressibility | Low (behaves like a solid) |

| Common Perception | Generally considered a solid food item |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Scientific Definition of Liquid

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, challenges our understanding of physical states. To determine if it qualifies as a liquid, we must first dissect the scientific definition of a liquid. A liquid is traditionally defined as a state of matter that takes the shape of its container, has a fixed volume, and flows under its own weight. These properties arise from the loose arrangement of molecules, which allows them to move past one another while maintaining a relatively constant density.

Consider the molecular behavior of liquids. In a liquid, molecules are close together but not rigidly structured, enabling them to slide over one another. This is why liquids flow and adapt to their containers. Water, for instance, exemplifies these traits perfectly. Cheese, however, presents a paradox. Its molecular structure is more complex, composed of proteins, fats, and moisture held in a semi-solid matrix. While cheese can deform under pressure, it does not flow freely like a liquid. This raises the question: does partial conformity to liquid behavior qualify cheese as a liquid?

To answer this, examine the role of temperature and pressure. Liquids typically transition between states more readily than solids. For example, water becomes a gas at 100°C (212°F) at sea level. Cheese, when heated, melts into a viscous substance that resembles a liquid. However, this transformation is not a direct shift to a liquid state but rather a breakdown of its solid structure. The melted cheese retains enough internal cohesion to resist true liquidity, as evidenced by its tendency to cling together rather than disperse uniformly.

From a practical standpoint, classifying cheese as a liquid has implications for culinary science and food storage. If cheese were a liquid, it would require different handling procedures, such as airtight containers to prevent spillage. Yet, in kitchens worldwide, cheese is treated as a solid, sliced, grated, or melted without the precautions reserved for liquids. This functional distinction underscores the importance of context in scientific definitions. While cheese exhibits some liquid-like properties, its overall behavior aligns more closely with solids, making its classification as a liquid scientifically inaccurate.

In conclusion, the scientific definition of a liquid hinges on molecular arrangement and behavior. Cheese, with its semi-solid structure and limited flow, does not meet these criteria. While it can be manipulated into a liquid-like state through heat, this transformation is temporary and does not redefine its fundamental nature. Understanding these distinctions not only clarifies the debate over cheese’s state but also highlights the precision required in scientific classification.

Starbucks Egg and Protein Box: Uncovering the Cheese Content

You may want to see also

Cheese's Physical Properties

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, defies simple categorization in terms of physical state. Its texture ranges from soft and spreadable, like Brie, to hard and crumbly, like Parmesan. This variability arises from differences in moisture content, fat levels, and the curdling process. For instance, fresh cheeses like mozzarella contain approximately 50-60% water, while aged varieties like cheddar have as little as 30-40%. Understanding these properties is crucial for culinary applications, as they dictate how cheese melts, stretches, or holds its shape in dishes.

Consider the melting behavior of cheese, a property tied to its protein and fat composition. Cheeses high in moisture and low in calcium, such as provolone or gouda, melt smoothly and evenly, making them ideal for sauces or sandwiches. Conversely, low-moisture cheeses like halloumi resist melting due to their dense protein matrix, allowing them to hold their structure when grilled or fried. To optimize melting, heat cheese gradually at temperatures between 120°F and 180°F (49°C to 82°C), avoiding direct high heat, which can cause oil separation or rubbery textures.

The question of whether cheese is a liquid hinges on its rheological properties—how it deforms and flows under stress. Soft cheeses like cream cheese exhibit viscoelastic behavior, flowing slowly under pressure while retaining some solid-like characteristics. This duality is evident when spreading cheese on bread; it conforms to the surface without losing its cohesive structure. In contrast, harder cheeses behave more like solids until subjected to heat or mechanical force, such as grating or slicing. This distinction highlights why cheese cannot be strictly classified as a liquid but rather exists in a transitional state between solid and liquid.

Practical tips for working with cheese’s physical properties include storing it properly to maintain texture. Wrap semi-soft cheeses like cheddar in wax or parchment paper to retain moisture, and store them at 35°F to 40°F (2°C to 4°C). For harder cheeses, allow them to come to room temperature before serving to enhance flavor and texture. When incorporating cheese into recipes, consider its moisture content: drier cheeses like pecorino can absorb liquid from dishes, while wetter cheeses like ricotta may release excess water, affecting consistency. By leveraging these properties, cooks can achieve desired outcomes, whether crafting a creamy fondue or a crispy cheese topping.

Unveiling the Creamy Cheese Filling Inside Traditional Paczki Delights

You may want to see also

Melting Point of Cheese

Cheese, a beloved dairy product, undergoes a fascinating transformation when heated, raising the question: does it become a liquid? The melting point of cheese is not a single temperature but a range, influenced by its composition. For instance, mozzarella, with its high moisture content, begins to melt around 130°F (54°C), making it ideal for pizzas and lasagnas. In contrast, cheddar, a harder cheese with lower moisture, requires temperatures between 150°F and 180°F (65°C to 82°C) to achieve a smooth, molten state. Understanding these thresholds is crucial for culinary perfection, ensuring cheese melts evenly without burning or separating.

Analyzing the science behind cheese’s melting point reveals its dependence on fat and protein content. Cheeses like Gruyère, rich in fat and protein, melt smoothly due to their ability to form a cohesive emulsion when heated. Conversely, low-fat cheeses like cottage cheese lack sufficient fat to create this effect, often remaining lumpy or refusing to melt altogether. This highlights why not all cheeses behave the same under heat, dispelling the myth that cheese universally transitions into a liquid state.

For home cooks, mastering the melting point of cheese involves precision and experimentation. Start by preheating your oven or stovetop to the lower end of the cheese’s melting range. Gradually increase the temperature, monitoring closely to avoid overheating. For example, when making a grilled cheese sandwich, maintain a medium heat to allow the cheese (such as American or provolone) to melt slowly without burning the bread. Pairing cheeses with complementary melting points, like combining mozzarella and cheddar, can also create a balanced texture in dishes like macaroni and cheese.

A comparative look at cheese melting points across cultures reveals intriguing variations. In France, raclette cheese is melted at around 158°F (70°C) and scraped onto potatoes and meats, showcasing its unique melting properties. Meanwhile, in Mexico, Oaxaca cheese, with a melting point similar to mozzarella, is used to create stretchy, gooey textures in dishes like quesadillas. These examples illustrate how different cultures leverage the melting characteristics of cheese to enhance their culinary traditions.

Finally, practical tips can elevate your cheese-melting game. Always shred or slice cheese into uniform pieces to ensure even melting. Avoid overcooking, as prolonged heat can cause the proteins to tighten, expelling oil and creating a greasy texture. For sauces, incorporate cheese gradually, stirring constantly to maintain a smooth consistency. By respecting the melting point of cheese and applying these techniques, you can transform this solid dairy product into a luscious, liquid-like delight, proving that while cheese isn’t inherently a liquid, it can certainly behave like one under the right conditions.

Exploring Cheese Sales: From Markets to Modern Retail Strategies

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Legal Classification of Cheese

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, often sparks debates about its physical state. While scientifically, cheese is classified as a solid due to its structure, legal definitions can vary, particularly in contexts like customs, taxation, and food regulations. These classifications are not just academic; they have real-world implications for producers, importers, and consumers. For instance, the European Union’s customs code categorizes cheese under specific tariff headings based on its type, moisture content, and production method, which directly affects import duties. Understanding these legal nuances is crucial for navigating the global cheese market.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines cheese as a food product made from milk, but its legal classification can shift depending on the context. For example, in a 2018 court case, a dispute arose over whether cheese should be considered a liquid when determining weight limits for transportation. The ruling hinged on the cheese’s moisture content and its behavior under pressure, highlighting how legal interpretations can diverge from everyday understanding. This case underscores the importance of precise definitions in industries where compliance with weight and safety regulations is critical.

Contrastingly, in the realm of international trade, cheese’s classification often revolves around its moisture content and intended use. The World Customs Organization (WCO) uses the Harmonized System (HS) to classify goods, including cheese, into specific categories. For example, fresh cheeses with high moisture content (e.g., mozzarella, over 55% water) are classified differently from hard cheeses (e.g., cheddar, under 52% water). These distinctions impact tariffs, quotas, and even food safety standards, making accurate classification essential for businesses operating across borders.

From a practical standpoint, producers and importers must meticulously document cheese characteristics to comply with legal standards. For instance, the EU requires detailed labeling, including fat content in dry matter (e.g., "45% fat i.d.m." for Gouda), which influences its classification and taxation. Similarly, in the U.S., the FDA mandates that cheese labels specify milk type (cow, goat, etc.) and additives, ensuring transparency for consumers. Misclassification can result in fines, delays, or even product seizures, emphasizing the need for diligence in adhering to legal definitions.

In conclusion, while cheese is undeniably solid in everyday terms, its legal classification is far more complex and context-dependent. Whether for customs, transportation, or food safety, understanding these distinctions is vital for stakeholders in the cheese industry. By staying informed about regulatory requirements and maintaining accurate documentation, producers and importers can navigate the legal landscape effectively, ensuring compliance and minimizing risks. Cheese may not be a liquid, but its legal status is anything but solid.

Mastering the Art of Cutting Block Cheese: Tips and Techniques

You may want to see also

Cultural Perceptions of Cheese

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, defies simple categorization. Its state—solid, semi-solid, or liquid—varies by type, temperature, and cultural context. In France, for instance, cheese is often served at room temperature, where a Brie or Camembert can become so soft it borders on liquid. This contrasts with American perceptions, where cheese is more commonly consumed cold and firm, as in slices of cheddar or blocks of mozzarella. The question "Is cheese a liquid?" thus becomes a cultural lens, revealing how societies interact with and define this versatile food.

Consider the role of cheese in culinary traditions. In Italy, melted mozzarella on a pizza or in a lasagna is celebrated for its gooey, almost liquid texture, enhancing both flavor and mouthfeel. This fluidity is intentional, a hallmark of the dish’s authenticity. Conversely, in Switzerland, fondue—a communal dish of melted cheese—is carefully prepared to maintain a viscous, dip-able consistency, neither solid nor fully liquid. These examples illustrate how cultural practices shape not only the perception of cheese’s state but also its ideal form in specific contexts.

From a scientific standpoint, cheese is a gel—a semi-solid system where proteins and fats suspend liquid. However, cultural perceptions often override this technicality. In the Middle East, Akkawi cheese is soaked in brine, becoming so soft it can be spread like butter, blurring the line between solid and liquid. Similarly, in Mexico, Oaxaca cheese is stretched into thin strands that melt seamlessly into dishes like quesadillas, its fluid-like behavior integral to the cuisine. These regional adaptations highlight how cultural utility, not scientific classification, dictates cheese’s perceived state.

Practical tips for navigating this fluidity abound. For instance, when cooking with cheese, consider its moisture content: high-moisture cheeses like fresh mozzarella or goat cheese will melt more readily, approaching a liquid state, while low-moisture cheeses like Parmesan retain their structure. Pairing cheese with temperature-appropriate dishes is also key—serve semi-soft cheeses at room temperature to enhance their spreadability, or chill hard cheeses to maintain their firmness. Understanding these nuances allows for better integration of cheese into diverse culinary traditions, respecting both its cultural significance and physical properties.

Ultimately, the question of whether cheese is a liquid transcends science, rooted instead in cultural perception and application. From the runny centers of French cheeses to the stretchy strands of Mexican Oaxaca, cheese’s state is as much about context as composition. By embracing these variations, we not only enrich our culinary experiences but also honor the global heritage of this beloved food. Whether solid, semi-solid, or liquid, cheese remains a unifying element across cultures, its form ever-adaptable to the needs and traditions of those who savor it.

Mastering Camembert: A Step-by-Step Guide to Perfectly Matured Cheese

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, cheese is not considered a liquid. It is a solid food product made from milk.

Some argue that cheese can melt and flow like a liquid when heated, but this does not classify it as a liquid in its natural state.

No, even though some cheeses are soft or semi-soft, their texture does not change their classification as a solid food.

No, cheese is not classified as a liquid for travel or shipping regulations, as it is a solid food item.

While cheese can melt and behave like a liquid when heated, it is still treated as a solid ingredient in recipes and cooking instructions.