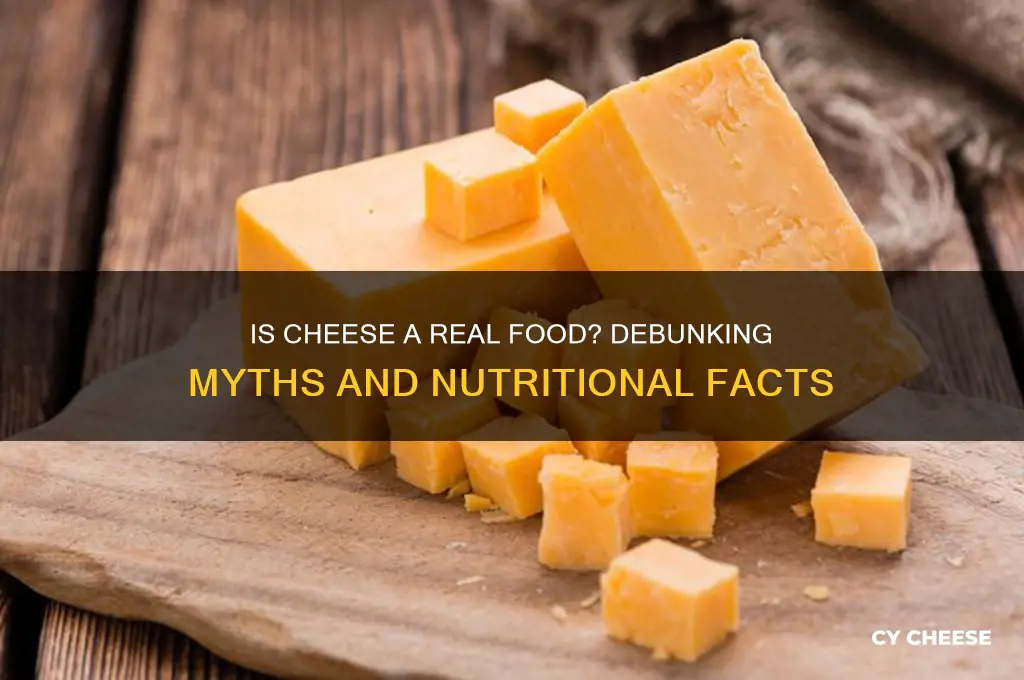

The question of whether cheese is a real food sparks intriguing debates, as it straddles the line between natural and processed products. Cheese is undeniably derived from milk, a natural food source, but its transformation involves fermentation, culturing, and often pasteurization, raising questions about its authenticity. While artisanal, minimally processed cheeses retain much of their natural essence, mass-produced varieties may contain additives, preservatives, and artificial ingredients, blurring the lines further. Ultimately, whether cheese qualifies as real food depends on its production methods and ingredients, inviting a nuanced discussion about what constitutes genuine, wholesome nourishment in today's food landscape.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Cheese is a dairy product made from milk, typically from cows, goats, or sheep, through a process of curdling and draining. |

| Nutritional Value | Rich in protein, calcium, phosphorus, zinc, vitamin A, riboflavin (B2), and vitamin B12. Also contains saturated fats and calories. |

| Food Group | Classified as a dairy product and a source of protein. |

| Processing | Involves fermentation, curdling, pressing, and aging, which transforms milk into a solid food. |

| Cultural Significance | A staple food in many cultures worldwide, with thousands of varieties. |

| Dietary Role | Considered a real food as it provides essential nutrients and is part of balanced diets (e.g., Mediterranean, keto). |

| Health Concerns | High saturated fat and sodium content may pose risks for heart health if consumed in excess. |

| Regulatory Status | Recognized as a food by regulatory bodies like the FDA and EFSA. |

| Culinary Use | Used as an ingredient, topping, or standalone food in various dishes globally. |

| Shelf Life | Varies by type; ranges from a few weeks to several years depending on aging and preservation methods. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Nutritional Value: Cheese provides protein, calcium, and vitamins, making it a nutritious food choice

- Processing Methods: Natural cheeses vs. highly processed varieties and their food status

- Cultural Significance: Cheese as a staple in diets worldwide, validating its real food status

- Ingredient Debate: Is cheese considered real food if made from milk and bacteria

- Health Concerns: Balancing cheese's benefits with potential drawbacks like saturated fats

Nutritional Value: Cheese provides protein, calcium, and vitamins, making it a nutritious food choice

Cheese is undeniably a real food, and its nutritional profile underscores its value in a balanced diet. A single ounce of cheddar cheese, for instance, delivers 7 grams of protein, which is essential for muscle repair and growth. This makes cheese a convenient, high-quality protein source, particularly for those who may not consume meat. Protein is not the only benefit; the same serving provides 20% of the daily recommended calcium intake, vital for bone health and nerve function. For individuals at risk of osteoporosis, especially postmenopausal women and older adults, incorporating cheese into meals can be a practical way to meet calcium needs without relying solely on supplements.

Beyond protein and calcium, cheese is a rich source of vitamins, particularly vitamin B12 and vitamin A. Vitamin B12, found abundantly in dairy products like cheese, is critical for red blood cell formation and neurological function. A deficiency in this vitamin can lead to anemia and cognitive issues, making cheese an important dietary component, especially for vegetarians who may lack B12 from animal sources. Vitamin A, another nutrient present in cheese, supports immune function, vision, and skin health. For children and adolescents, whose bodies are rapidly developing, including moderate portions of cheese in their diet can help ensure they receive these essential vitamins.

However, the nutritional benefits of cheese should be balanced with awareness of its fat and sodium content. While cheese provides saturated fats, which should be consumed in moderation, opting for low-fat varieties like part-skim mozzarella or Swiss cheese can mitigate this concern. Similarly, sodium levels vary widely among cheese types; feta and halloumi are higher in sodium, while cottage cheese and ricotta are lower. For individuals with hypertension or those monitoring sodium intake, choosing lower-sodium options and practicing portion control—such as limiting servings to 1–2 ounces per day—can maximize cheese’s nutritional benefits without adverse effects.

Incorporating cheese into meals strategically can enhance both flavor and nutrition. For example, adding shredded cheese to a vegetable omelet boosts protein and calcium intake while encouraging consumption of nutrient-dense vegetables. Pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or apples can also slow digestion, promoting satiety and stabilizing blood sugar levels. For parents, using cheese as a dip for raw veggies can make healthy snacks more appealing to picky eaters. By understanding cheese’s nutritional strengths and limitations, it becomes clear that when consumed mindfully, cheese is not only a real food but a valuable addition to a wholesome diet.

When Did Chuck E. Cheese Remove the Stage? A Timeline

You may want to see also

Processing Methods: Natural cheeses vs. highly processed varieties and their food status

Cheese, in its most natural form, is a product of milk, bacteria, and time. Traditional methods involve curdling milk with rennet or acids, separating curds from whey, and aging the result under controlled conditions. This process retains much of the milk’s inherent nutrients, such as protein, calcium, and vitamins, while introducing beneficial probiotics from fermentation. Natural cheeses like cheddar, Gruyère, and Brie are minimally altered, preserving their status as a "real food" by maintaining their nutritional integrity and relying on simple, time-honored techniques.

Highly processed cheese varieties, on the other hand, undergo significant alterations to enhance shelf life, texture, and uniformity. These products often include additives like emulsifiers, stabilizers, and artificial flavors. For instance, American cheese singles contain sodium citrate to maintain smoothness and preservatives like sorbic acid to prevent spoilage. While these modifications make processed cheeses convenient and consistent, they dilute the nutritional profile and introduce ingredients that some consumers may prefer to avoid. The question arises: does heavy processing strip cheese of its "real food" status, or does it simply transform it into a different category of edible product?

To compare, consider the ingredient lists. A block of aged Gouda typically contains milk, cultures, salt, and enzymes—nothing more. In contrast, a processed cheese product might list milk, whey, milk protein concentrate, vegetable oil, and a host of stabilizers. The latter is engineered for stability and mass production, often at the expense of the natural complexity and health benefits found in its minimally processed counterpart. For those prioritizing whole, unaltered foods, natural cheeses clearly align better with the definition of "real food."

Practical considerations come into play when choosing between the two. Natural cheeses require refrigeration and have shorter shelf lives, while processed varieties can last months without spoiling. For families or individuals seeking convenience, processed cheese may be a viable option, but it’s essential to weigh this against the nutritional trade-offs. A tip for balancing both worlds: use natural cheeses as the primary source and reserve processed varieties for occasional, specific uses, like melting in recipes where texture is critical.

Ultimately, the distinction between natural and highly processed cheeses hinges on how one defines "real food." If real food means nutrient-dense, minimally altered, and free from artificial additives, natural cheeses fit the bill. Processed varieties, while convenient and versatile, deviate from this ideal. The choice depends on individual priorities—whether nutritional purity, convenience, or a compromise between the two takes precedence. Understanding the processing methods empowers consumers to make informed decisions aligned with their dietary values.

Discover the Unique, Creamy, and Tangy Flavor of Wensleydale Cheese

You may want to see also

Cultural Significance: Cheese as a staple in diets worldwide, validating its real food status

Cheese is a global culinary cornerstone, embedded in the diets of diverse cultures for millennia. From the creamy Brie of France to the pungent Epoisses of Norway, cheese transcends borders, reflecting local traditions and ingredients. This universality underscores its status as a real food, not merely a processed novelty.

Historically, cheese emerged as a practical solution for preserving milk, allowing communities to store nutrients through seasons of scarcity. Today, it remains a staple in diets worldwide, providing protein, calcium, and essential vitamins. In countries like Italy, Greece, and Switzerland, cheese is not just a food but a cultural emblem, integral to daily meals and festive occasions.

Consider the Mediterranean diet, renowned for its health benefits. Cheese, particularly feta and pecorino, features prominently in this regimen, often paired with olive oil, vegetables, and whole grains. Studies suggest that moderate consumption of cheese within this dietary pattern can reduce the risk of heart disease and improve bone health. For instance, a 30g serving of cheese daily, as part of a balanced diet, can contribute to meeting the recommended calcium intake for adults (1,000–1,200 mg/day).

In contrast, the French paradox highlights another dimension of cheese’s cultural significance. Despite a diet rich in saturated fats, including cheese, the French exhibit lower rates of cardiovascular disease. Researchers attribute this to the holistic approach to eating, where cheese is savored in moderation, alongside a lifestyle that values mealtime as a social, unhurried experience. This example illustrates how cheese, when integrated into a mindful diet, can coexist with health and longevity.

For those incorporating cheese into their diets, practical tips can maximize its benefits. Opt for artisanal or locally produced cheeses, which often contain live cultures beneficial for gut health. Pair cheese with fiber-rich foods like apples or whole-grain crackers to balance its fat content. For children and older adults, cheese can be a palatable way to boost calcium intake, but portion control is key—a 20g serving for kids aged 4–8 and 30g for adults over 50 aligns with dietary guidelines.

In conclusion, cheese’s enduring presence across cultures and its nutritional contributions validate its status as a real food. Its adaptability to various diets, from Mediterranean to Nordic, demonstrates its versatility and value. By understanding its cultural and health contexts, individuals can enjoy cheese as both a culinary delight and a nourishing staple.

Cheese Toss: What Happens When You Throw Cheese at Your Dog?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ingredient Debate: Is cheese considered real food if made from milk and bacteria?

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, is fundamentally a product of milk and bacteria. This simple transformation raises a nuanced question: does the process of fermentation and coagulation elevate cheese to the status of "real food"? To answer this, consider the definition of real food, often associated with minimal processing and nutritional value. Cheese fits this criterion, as it retains essential nutrients from milk, such as protein, calcium, and vitamins, while introducing beneficial probiotics from bacterial cultures. However, the debate intensifies when examining highly processed cheese variants, which may include additives and preservatives.

Analyzing the production process reveals why cheese qualifies as real food. Traditional cheese-making involves curdling milk with bacterial cultures and rennet, followed by aging. This method preserves the integrity of the ingredients, transforming them into a dense, nutrient-rich product. For instance, a 30g serving of cheddar provides 7g of protein and 20% of the daily calcium requirement. Even aged cheeses, like Parmesan, offer concentrated nutritional benefits. The key lies in moderation and choosing varieties with minimal additives, ensuring the final product aligns with the principles of real food.

From a comparative perspective, cheese stands apart from ultra-processed foods, which often contain artificial flavors, colors, and stabilizers. While some processed cheese products blur this line, artisanal and natural cheeses maintain their status as real food. For example, a study in the *Journal of Food Science* highlights that fermented dairy products, including cheese, contribute to gut health due to their probiotic content. This contrasts sharply with processed snacks, which lack such benefits. By focusing on ingredient lists and opting for cheeses made solely from milk, bacteria, and salt, consumers can confidently categorize cheese as real food.

Practically, incorporating cheese into a balanced diet requires mindful selection. For children over 12 months, mild cheeses like mozzarella or Swiss provide calcium without excessive sodium. Adults can experiment with aged varieties, such as Gouda or Gruyère, for added flavor and nutritional density. A tip for discerning real cheese: check for a short ingredient list and avoid products labeled as "cheese food" or "cheese product," which often contain fillers. Pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods, like whole-grain crackers or apples, enhances digestion and nutrient absorption, reinforcing its role as a wholesome, real food option.

In conclusion, cheese made from milk and bacteria qualifies as real food due to its minimal processing, nutrient retention, and health benefits. The debate hinges on distinguishing between traditional and highly processed varieties. By prioritizing natural cheeses and understanding their production, consumers can confidently embrace cheese as a valuable component of a real food diet.

Cheese Points on WW Freestyle: Smart Snacking Guide

You may want to see also

Health Concerns: Balancing cheese's benefits with potential drawbacks like saturated fats

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, offers a complex nutritional profile that sparks debate. While it’s rich in protein, calcium, and vitamins like B12, its saturated fat content raises health concerns. A single ounce of cheddar, for instance, contains about 6 grams of fat, with nearly 4 grams being saturated—over 20% of the daily recommended limit for a 2,000-calorie diet. This duality demands a nuanced approach to consumption, especially for those monitoring heart health or weight.

Consider the benefits first. Cheese provides essential nutrients like phosphorus and zinc, and its protein content supports muscle repair and satiety. For older adults, moderate cheese intake can aid bone density, thanks to its calcium and vitamin D. However, the saturated fat in cheese can elevate LDL cholesterol, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Studies suggest that the impact varies by individual—genetics, overall diet, and lifestyle play significant roles. For example, pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or vegetables can mitigate its fat absorption.

Balancing cheese’s pros and cons requires portion control and mindful selection. Opt for lower-fat varieties like mozzarella (1.5g saturated fat per ounce) or Swiss (5g per ounce) instead of cream cheese (5g per ounce) or blue cheese (6g per ounce). Limit daily intake to 1–2 ounces, particularly for children and adults over 50, who may have lower caloric needs. Incorporate cheese into meals rather than snacking on it alone to avoid overconsumption.

Practical tips can further optimize cheese’s role in a healthy diet. Use strong-flavored cheeses like Parmesan sparingly—a small sprinkle adds richness without excessive fat. Experiment with plant-based alternatives, which often contain less saturated fat but check labels for added sodium or preservatives. For those with lactose intolerance, aged cheeses like cheddar or Gruyère are naturally lower in lactose, offering a digestive-friendly option.

In conclusion, cheese can be a real food in a balanced diet, but its saturated fat content warrants moderation. By choosing wisely, controlling portions, and pairing it with nutrient-dense foods, you can enjoy its benefits while minimizing health risks. As with any food, context matters—cheese’s role in your diet depends on your individual health goals, age, and lifestyle.

Perfect Cheese Portions: How Much for 50 Sandwiches?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, cheese is a real food. It is made from milk through a process of curdling and aging, resulting in a nutrient-dense product.

Cheese is made from natural ingredients (milk, bacteria, enzymes, and salt) and undergoes traditional fermentation and aging processes, distinguishing it from heavily processed foods with artificial additives.

Yes, cheese can be part of a healthy diet when consumed in moderation. It provides protein, calcium, and other essential nutrients, though it is also high in fat and sodium.

Most cheeses are considered real food, but highly processed cheese products (like cheese spreads or singles) may contain artificial additives, making them less natural.

Cheese is generally considered a processed food because it is transformed from its raw state (milk), but it is minimally processed compared to ultra-processed foods, retaining its nutritional value.