Cheese, a beloved dairy product enjoyed worldwide, often raises questions about its properties, particularly its resistance to acidic environments. The inquiry into whether cheese is acid resistant stems from its composition, primarily consisting of proteins, fats, and minerals, which can interact differently with acidic substances. Understanding this resistance is crucial, as it impacts not only culinary applications, such as pairing cheese with acidic foods like wine or tomatoes, but also its behavior in the digestive system. Factors like the type of cheese, its pH level, and the acidity of the environment play significant roles in determining its resistance. Exploring this topic sheds light on the science behind cheese and its versatility in various contexts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

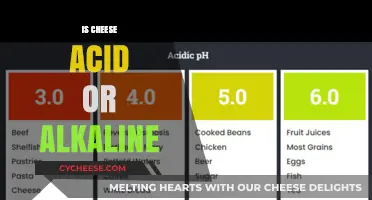

| Acid Resistance | Cheese is generally not acid-resistant; its pH typically ranges from 5 to 6, making it slightly acidic but vulnerable to further acid exposure. |

| pH Level | 5.0–6.0 (varies by type; e.g., Cheddar ~5.0, Mozzarella ~5.2) |

| Effect of Acid Exposure | Prolonged exposure to acids (e.g., vinegar, citrus) can cause curdling, texture breakdown, and flavor alteration. |

| Melting Behavior in Acidic Sauces | Cheese may separate or become grainy when melted in acidic sauces due to destabilization of proteins and fats. |

| Storage in Acidic Environments | Not recommended; acidic conditions can accelerate spoilage and affect taste. |

| Common Acid-Sensitive Types | Fresh cheeses (e.g., ricotta, mozzarella) are more sensitive than aged cheeses (e.g., cheddar, parmesan). |

| Culinary Applications | Best used in neutral or mildly acidic dishes; avoid direct pairing with strong acids unless recipes account for curdling. |

| Preservation Methods | Acid resistance is not a factor in cheese preservation; methods like refrigeration and waxing are used instead. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Natural Cheese pH Levels: Most cheeses have pH 5-6, resisting acid degradation due to low acidity

- Acid-Curdling Process: Acid coagulates milk proteins, forming cheese curds, a key step in production

- Lactic Acid Bacteria: These bacteria ferment lactose, producing lactic acid, crucial for cheese flavor and texture

- Acid Resistance Mechanisms: Cheese proteins and fats protect against acid breakdown, ensuring stability in acidic environments

- Storage in Acidic Foods: Cheese retains structure when paired with acidic ingredients like tomatoes or vinegar

Natural Cheese pH Levels: Most cheeses have pH 5-6, resisting acid degradation due to low acidity

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, boasts a pH level typically ranging between 5 and 6. This slightly acidic environment is a critical factor in its resistance to acid degradation. To understand why, consider the pH scale: 7 is neutral, below 7 is acidic, and above 7 is basic. The pH of cheese places it in a zone where it’s neither highly acidic nor alkaline, creating a stable structure that resists breakdown by external acids. For instance, when cheese is exposed to acidic ingredients like vinegar or citrus, its internal pH acts as a buffer, minimizing the impact and preserving its texture and flavor.

Analyzing the science behind this resistance reveals the role of casein, the primary protein in cheese. Casein molecules form a protective matrix that stabilizes the cheese’s structure, even in mildly acidic conditions. This matrix is further strengthened during the cheesemaking process, where curds are formed and acids (like lactic acid) are produced naturally. The low acidity of cheese, combined with this protein framework, ensures it remains intact when introduced to acidic environments. For example, adding cheese to a tomato-based sauce (pH ~4.0) doesn’t cause it to dissolve, thanks to its inherent pH buffering capacity.

From a practical standpoint, understanding cheese’s pH levels can guide culinary applications. Soft cheeses like mozzarella (pH ~5.3) and hard cheeses like cheddar (pH ~5.8) both resist acid degradation, but their textures respond differently. Soft cheeses may soften slightly in acidic dishes, while hard cheeses retain their structure. To maximize flavor and texture, pair cheeses with acidic ingredients thoughtfully. For instance, a sprinkle of feta (pH ~5.2) on a lemon-dressed salad enhances the dish without losing its crumbly texture. Avoid prolonged exposure to highly acidic mediums, as even cheese’s resistance has limits.

Comparatively, cheese’s pH-driven resilience sets it apart from other dairy products. Milk, with a pH of ~6.7, is more susceptible to acid degradation, curdling when exposed to lemon juice or vinegar. Cheese’s lower pH and solidified structure provide a natural defense mechanism. This distinction is particularly useful in cooking, where cheese can be used as a stabilizing agent in acidic recipes. For example, adding grated Parmesan (pH ~5.5) to a risotto with white wine (pH ~3.0–4.0) enriches the dish without causing separation or curdling.

In conclusion, cheese’s pH range of 5–6 is a key to its acid resistance, rooted in its protein structure and natural acidity. This property not only preserves its integrity in acidic dishes but also makes it a versatile ingredient in the kitchen. By leveraging this knowledge, cooks can confidently incorporate cheese into a variety of recipes, ensuring optimal flavor and texture. Whether melting Gruyère (pH ~5.6) into French onion soup or crumbling goat cheese (pH ~5.4) over a tart vinaigrette, cheese’s pH acts as a silent guardian against acid degradation.

Mastering the Art of Importing Authentic French Cheeses: A Guide

You may want to see also

Acid-Curdling Process: Acid coagulates milk proteins, forming cheese curds, a key step in production

Cheese production hinges on the acid-curdling process, a delicate dance where acidity transforms liquid milk into solid curds. This pivotal step relies on lowering milk’s pH, typically from 6.6 to around 5.0, through the activity of lactic acid bacteria or direct acid addition. At this pH, milk proteins (primarily casein) lose their negative charge, allowing them to bind together and form a gel-like structure. The result? Curds, the foundation of every cheese.

Consider the precision required: too little acid, and curds remain soft or fail to form; too much, and the curds become brittle, expelling excess whey. For example, in fresh cheeses like ricotta, a rapid acidification (often using vinegar or citric acid) creates fine, tender curds. In contrast, aged cheeses like cheddar rely on slower bacterial acidification, producing firmer, more complex curds. Dosage matters: citric acid, when used, is typically added at 0.5–1.0% by weight of milk, while vinegar requires 2–3 tablespoons per gallon.

The acid-curdling process isn’t just about structure—it’s a flavor architect. As pH drops, enzymes in the milk are activated, breaking down proteins and lactose into compounds that contribute to the cheese’s eventual taste profile. This is why acid-coagulated cheeses often have a tangy, bright character. However, this method lacks the proteolytic enzymes found in rennet, limiting the complexity achievable in aged varieties.

Practical tip: For home cheesemakers, controlling temperature is critical. Acid-curdling works best between 75–85°F (24–29°C). Use a thermometer and avoid overheating, as this can denature proteins and ruin curd formation. Additionally, stir gently during acid addition to ensure even distribution without breaking the curds prematurely.

In summary, the acid-curdling process is both art and science, demanding precision in pH, temperature, and technique. While it’s simpler than rennet-based methods, it offers a unique pathway to crafting cheeses with distinct textures and flavors. Whether you’re making a quick batch of paneer or experimenting with cultured cheeses, understanding this process unlocks a world of possibilities in the kitchen.

Mastering Artisan Cheese Sales: Tips for Showcasing and Selling Unique Flavors

You may want to see also

Lactic Acid Bacteria: These bacteria ferment lactose, producing lactic acid, crucial for cheese flavor and texture

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are the unsung heroes of cheese production, transforming milk into a complex, flavorful, and textured food product. These microorganisms, including species like *Lactobacillus* and *Streptococcus*, thrive in the lactose-rich environment of milk, fermenting it into lactic acid. This process not only preserves the milk but also initiates the coagulation of proteins, a critical step in cheese making. The acidity produced by LAB lowers the pH of the milk, causing it to curdle and separate into curds and whey. Without this bacterial activity, cheese as we know it would not exist.

The role of lactic acid in cheese goes beyond mere preservation. It acts as a flavor enhancer, contributing tangy, sharp, or mild notes depending on the type and amount produced. For instance, aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan owe their pronounced flavors to prolonged lactic acid activity. Texture is equally influenced; the acid’s interaction with milk proteins determines whether a cheese will be soft and creamy (e.g., Brie) or hard and crumbly (e.g., feta). Cheese makers often control LAB strains and fermentation conditions to achieve specific flavor and texture profiles, making these bacteria indispensable in artisanal and industrial cheese production alike.

From a practical standpoint, understanding LAB’s role allows home cheese makers to troubleshoot common issues. For example, if a cheese lacks tanginess, it may be due to insufficient lactic acid production, often caused by low starter culture dosage or improper fermentation temperature. A typical starter culture contains 1–2% LAB by weight of the milk, and fermentation temperatures range from 20°C to 40°C, depending on the cheese variety. Monitoring pH levels during the process—aiming for a drop from 6.6 to around 5.0—ensures optimal acid development. This precision transforms cheese making from an art into a science.

Comparatively, LAB’s acid resistance is a double-edged sword. While their ability to survive in acidic environments is vital for cheese production, it also poses challenges in controlling fermentation. Overproduction of lactic acid can lead to bitter flavors or excessively hard textures. To mitigate this, cheese makers often introduce secondary bacteria or molds (e.g., in blue cheese) to balance acidity. Additionally, aging cheese allows lactic acid to mellow, smoothing out harsh flavors. This interplay between LAB and other microorganisms highlights the delicate balance required in cheese making.

In conclusion, lactic acid bacteria are not just acid-resistant; they are acid-producing powerhouses that define cheese’s character. Their fermentation of lactose into lactic acid is the cornerstone of cheese flavor and texture, offering both opportunities and challenges for cheese makers. By mastering LAB’s role, one can craft cheeses that range from mild and creamy to bold and complex. Whether in a professional dairy or a home kitchen, these bacteria remain the key to unlocking cheese’s full potential.

Is Italian Herbs and Cheese a White Sandwich? Exploring the Debate

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Acid Resistance Mechanisms: Cheese proteins and fats protect against acid breakdown, ensuring stability in acidic environments

Cheese, a dairy product revered for its versatility and flavor, exhibits remarkable resistance to acidic environments, a trait rooted in its molecular composition. Proteins and fats within cheese act as natural barriers against acid breakdown, preserving its structure and functionality. Casein, the primary protein in cheese, forms a protective matrix that resists denaturation under acidic conditions. This matrix not only shields the protein but also stabilizes the surrounding fats, preventing them from undergoing hydrolytic degradation. For instance, in cheeses like cheddar or Swiss, the casein micelles remain intact even when exposed to pH levels as low as 4.5, a common acidity in fermented foods.

To understand this mechanism further, consider the role of fat globules in cheese. These globules are encased in a membrane rich in phospholipids and proteins, which act as a buffer against acid-induced lipolysis. When cheese is subjected to acidic conditions, such as during aging or in acidic dishes like pizza or pasta sauces, these membranes minimize the interaction between fats and acid, slowing down the breakdown process. Practical applications of this resistance are evident in cooking; grated Parmesan sprinkled over a tomato-based sauce retains its texture and flavor despite the sauce’s acidity. For optimal results, add cheese to acidic dishes during the final stages of cooking to minimize prolonged exposure to low pH environments.

From a comparative perspective, the acid resistance of cheese proteins and fats contrasts sharply with other dairy products like milk or yogurt. Milk, for example, curdles immediately upon exposure to acids due to the rapid denaturation of its proteins. Cheese, however, undergoes a controlled curdling process during production, which preconditions its proteins and fats to withstand acidity. This distinction highlights the transformative power of cheese-making techniques, such as coagulation and aging, in enhancing acid resistance. For those experimenting with cheese in acidic recipes, opt for harder, aged varieties like Gruyère or Pecorino, which exhibit superior stability compared to softer cheeses.

Persuasively, the acid resistance of cheese proteins and fats opens doors for innovative culinary and industrial applications. In food preservation, cheese can serve as a stabilizing agent in acidic formulations, extending shelf life and maintaining product quality. For instance, incorporating cheese into salad dressings or marinades not only enhances flavor but also acts as a natural emulsifier, preventing separation. Industrially, cheese-derived proteins are being explored as acid-resistant coatings for food packaging, offering a sustainable alternative to synthetic materials. To harness this potential, food manufacturers can experiment with cheese powders or isolates in acidic products, ensuring a dosage of 5–10% by weight for effective stabilization.

In conclusion, the acid resistance of cheese is a testament to the intricate interplay between its proteins and fats. By forming protective matrices and buffered membranes, these components safeguard cheese against breakdown in acidic environments, ensuring its stability and functionality. Whether in the kitchen or the lab, understanding and leveraging these mechanisms can lead to creative solutions in food preparation and preservation. For home cooks and professionals alike, selecting the right cheese and managing its exposure to acidity are key steps in maximizing its resilience and flavor.

Mastering Aged Cheese Storage: Tips for Perfect Preservation and Flavor

You may want to see also

Storage in Acidic Foods: Cheese retains structure when paired with acidic ingredients like tomatoes or vinegar

Cheese, a culinary chameleon, often finds itself in the company of acidic ingredients like tomatoes, vinegar, or citrus. Yet, unlike some proteins that curdle or toughen under acidic conditions, cheese retains its structure remarkably well. This resilience stems from its unique composition: a protein matrix primarily of casein, which remains stable across a wide pH range. While extreme acidity can eventually break down cheese’s texture, moderate levels—such as those in marinara sauce or vinaigrettes—pose little threat. This makes cheese an ideal candidate for dishes where acidity is a key flavor component.

Consider the classic pairing of mozzarella and tomato in a caprese salad. The acidity of the tomatoes, with a pH around 4.3, does not cause the cheese to dissolve or lose its creamy texture. Similarly, in pickled cheese recipes, where vinegar (pH 2.0–3.4) is a dominant ingredient, the cheese remains intact, absorbing flavors without disintegrating. This is because the casein proteins in cheese are less reactive to acid compared to, say, milk proteins, which coagulate readily in acidic environments. For home cooks, this means cheese can be safely stored in acidic foods for short periods without compromising its integrity.

However, there are limits to cheese’s acid resistance. Prolonged exposure to highly acidic environments, such as storing cheese in undiluted vinegar for days, can lead to textural changes. The cheese may become firmer or develop a slightly grainy mouthfeel as the acid begins to break down its protein structure. To mitigate this, balance acidity with neutral ingredients or limit storage time. For instance, when marinating cheese in a vinegar-based brine, aim for 2–4 hours at room temperature or overnight in the refrigerator, depending on the desired flavor intensity.

Practical tips for leveraging cheese’s acid resistance include using harder cheeses like cheddar or gouda in acidic dishes, as their denser structure holds up better than softer varieties. When incorporating cheese into acidic sauces, add it toward the end of cooking to minimize heat and acid exposure. For storage, ensure acidic dishes containing cheese are refrigerated promptly, as cooler temperatures slow down any potential degradation. By understanding these nuances, you can confidently pair cheese with acidic ingredients, knowing it will retain its structure and enhance the dish’s overall appeal.

Freezing Ricotta Cheese: Texture and Taste Changes Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese is not entirely acid resistant, but its resistance depends on the type of cheese and the acidity level it is exposed to.

Yes, strong acids can break down cheese by denaturing its proteins and altering its texture, though milder acids may have less impact.

Cheese can partially dissolve or soften in acidic foods like tomato sauce due to the acid reacting with its proteins and fats.

Cheese can withstand stomach acid to some extent, but prolonged exposure may cause it to break down, depending on the cheese type and acidity level.