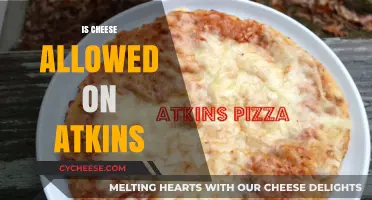

Cheese is often considered a staple in many diets worldwide, but its role as an antacid is a topic of debate. While some people believe that cheese can help neutralize stomach acid due to its calcium content, others argue that its high fat and protein levels may actually exacerbate acid reflux symptoms. The idea stems from the fact that calcium carbonate, a common ingredient in antacids, is present in dairy products like cheese. However, the overall effect of cheese on acid reflux can vary depending on individual tolerance, the type of cheese, and the amount consumed. This raises the question: can cheese truly act as an antacid, or does it contribute to the very problem it’s meant to alleviate?

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Is Cheese an Antacid? | No |

| Reason | Cheese is acidic (pH typically 5.0-5.9) and contains lactic acid, which can worsen acid reflux or heartburn in some individuals. |

| Antacid Properties | None; antacids are alkaline (pH >7) and neutralize stomach acid. |

| Common Antacids | Calcium carbonate, magnesium hydroxide, sodium bicarbonate, etc. |

| Cheese pH Range | 5.0 - 5.9 (acidic) |

| Effect on Acid Reflux | Can aggravate symptoms in sensitive individuals. |

| Calcium Content | High, but does not act as an antacid due to acidity. |

| Misconception | Cheese is sometimes mistakenly thought to neutralize acid due to its calcium content, but its acidity counteracts this effect. |

| Alternative Remedies | Almond milk, oatmeal, ginger, or actual antacid medications. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Cheese’s pH level and acidity

Cheese, a beloved dairy product, varies widely in its pH levels, which directly influence its acidity and potential effects on the body. Most cheeses have a pH range between 4.5 and 6.5, making them mildly acidic. This acidity is primarily due to the lactic acid produced during fermentation, a process where bacteria convert lactose into lactic acid. For context, a pH of 7 is neutral, while anything below 7 is acidic. Hard cheeses like Parmesan (pH 5.2–5.4) tend to be more acidic than softer varieties like mozzarella (pH 5.8–6.2). Understanding these pH levels is crucial when considering cheese as a potential antacid, as acidity plays a significant role in how it interacts with stomach acid.

Analyzing the relationship between cheese’s pH and its antacid properties reveals a counterintuitive truth: acidic foods do not typically neutralize stomach acid. Antacids work by raising the pH of stomach acid, making it less acidic. However, cheese’s mild acidity (pH 4.5–6.5) does not significantly alter stomach pH, which is naturally around 1.5–3.5. In fact, consuming acidic foods like cheese can sometimes exacerbate acid reflux or heartburn in sensitive individuals. While cheese may provide a temporary soothing effect due to its fat and protein content, which can slow digestion, its pH level does not qualify it as an effective antacid.

If you’re considering cheese as a remedy for acidity, proceed with caution. Start with small portions (1–2 ounces) of low-fat, mild cheeses like cottage cheese (pH 4.8–5.0) or fresh mozzarella. Avoid aged or highly acidic varieties like blue cheese (pH 4.5–5.0), as these can worsen symptoms. Pair cheese with alkaline foods like vegetables to balance acidity. For example, a small serving of cottage cheese with cucumber slices can be a gentler option. Always monitor your body’s response, as individual tolerance varies. For persistent acid reflux, consult a healthcare professional rather than relying on dietary experiments.

Comparing cheese to traditional antacids highlights its limitations. Over-the-counter antacids like Tums or Maalox contain alkaline compounds (e.g., calcium carbonate) that directly neutralize stomach acid, raising pH levels rapidly. Cheese, on the other hand, lacks these compounds and may even contribute to acidity due to its dairy content, which can stimulate acid production in some individuals. While cheese can be a comforting snack, it should not replace proven antacid treatments. Instead, view it as a complementary food that may provide temporary relief when consumed mindfully and in moderation.

Descriptively, the texture and flavor of cheese can create a sensory experience that distracts from discomfort, but this is not the same as addressing acidity at a chemical level. Creamy cheeses like Brie (pH 5.3–5.9) or Camembert offer a rich mouthfeel that can feel soothing, while sharper cheeses like Cheddar (pH 5.2–5.6) provide a bold flavor profile that may temporarily overshadow symptoms. However, these qualities do not equate to antacid action. For practical relief, focus on portion control and pairing cheese with non-acidic foods rather than relying on its pH properties. Cheese is a delightful addition to a balanced diet but not a substitute for targeted acid-neutralizing treatments.

Wisconsin Cheese and Sex: Unraveling the Unexpected Cultural Connection

You may want to see also

Calcium in cheese and acid neutralization

Cheese, a dairy staple, contains calcium, a mineral known for its role in bone health. But can this calcium act as an antacid, neutralizing stomach acid? The answer lies in understanding the chemical properties of calcium and its interaction with gastric acids. Calcium carbonate, a common antacid compound, works by releasing calcium ions that bind to stomach acid, reducing acidity. Cheese, while not as concentrated as calcium carbonate supplements, does contain calcium in a form that can contribute to acid neutralization. However, the effectiveness depends on the type of cheese and the amount consumed.

Consider this: a 30-gram serving of cheddar cheese provides approximately 200 mg of calcium. While this is a significant amount, it’s less than the 500–1,000 mg typically found in a single dose of calcium carbonate antacids. For occasional mild acid reflux, a small portion of cheese might offer temporary relief, but it’s not a substitute for medical-grade antacids. Hard cheeses like Parmesan or Swiss have higher calcium content per serving, making them slightly more effective in this regard. Soft cheeses, such as mozzarella or brie, contain less calcium and are less likely to impact stomach acidity.

From a practical standpoint, using cheese as an antacid requires moderation. Consuming large amounts to achieve significant acid neutralization could lead to other issues, such as increased calorie intake or lactose intolerance symptoms. For adults, a 1-ounce (28-gram) serving of hard cheese post-meal might help alleviate minor discomfort. However, individuals with severe acid reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) should consult a healthcare provider rather than relying on dietary sources like cheese. Children and pregnant women should also approach this method cautiously, as calcium needs vary and excessive intake can be harmful.

Comparatively, while cheese can contribute to acid neutralization, its role is limited. Antacids are formulated for quick relief, whereas cheese’s calcium is released more slowly during digestion. Additionally, cheese contains fats and proteins that may slow gastric emptying, potentially exacerbating acid reflux in some individuals. For those seeking natural remedies, calcium-rich alternatives like almond milk or leafy greens might be more effective without the added fats. Ultimately, cheese can be a minor player in managing acidity but should not replace proven treatments.

In conclusion, the calcium in cheese does have the potential to neutralize stomach acid, but its effectiveness is modest and context-dependent. For mild symptoms, a small serving of hard cheese might provide relief, but it’s not a reliable solution for chronic conditions. Pairing cheese with other low-acid foods and mindful portion control can maximize its benefits while minimizing risks. Always prioritize professional medical advice for persistent acid-related issues.

Discover the Delicious World of Cheese Crisps: A Tasty Snack Guide

You may want to see also

Cheese’s effect on stomach acid

Cheese, a dairy product rich in calcium and protein, often sparks curiosity about its effects on stomach acid. While not a traditional antacid, certain cheeses can influence gastric acidity due to their composition. For instance, hard cheeses like cheddar or Swiss contain higher fat content, which can slow gastric emptying and potentially reduce acid reflux symptoms by keeping the stomach fuller for longer. However, this effect varies depending on individual tolerance and portion size. Consuming large amounts of high-fat cheese may exacerbate acid production in some people, highlighting the importance of moderation.

Analyzing the role of calcium in cheese provides another perspective. Calcium carbonate, a common antacid ingredient, neutralizes stomach acid by reacting with hydrochloric acid to form water, carbon dioxide, and calcium chloride. Cheese, being calcium-rich, might offer a mild buffering effect, though it’s significantly less potent than over-the-counter antacids. For example, a 30g serving of cheddar provides about 200mg of calcium, far below the 500–1000mg dose typically found in antacid tablets. Thus, while cheese may contribute to acid neutralization, it’s not a reliable substitute for medication.

From a practical standpoint, incorporating cheese into a diet for acid management requires strategic planning. Soft, low-fat cheeses like mozzarella or cottage cheese are gentler on the stomach compared to aged, high-fat varieties. Pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods, such as whole-grain crackers or vegetables, can further mitigate acid-related discomfort by promoting digestion. For individuals with lactose intolerance, opting for lactose-free or aged cheeses (which contain minimal lactose) is advisable to avoid additional gastrointestinal issues.

Comparatively, cheese’s impact on stomach acid differs from that of traditional antacids in both mechanism and efficacy. Antacids act quickly to neutralize acid, providing immediate relief, whereas cheese’s effects are gradual and dependent on digestion. Additionally, antacids are formulated for precise dosing, whereas cheese lacks standardized measurements for acid control. This distinction underscores why cheese should be viewed as a complementary dietary choice rather than a primary treatment for acid-related conditions.

In conclusion, while cheese isn’t a conventional antacid, its calcium content and ability to slow gastric emptying can offer mild benefits for managing stomach acid. Practical tips include choosing low-fat options, monitoring portion sizes, and pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods. However, for severe or persistent acid issues, consulting a healthcare professional and relying on proven antacid treatments remains essential. Cheese can be a tasty addition to a balanced diet but should not replace targeted medical interventions.

Best Cheese Blade for Chef's Choice 615 Food Slicer Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$4.98 $5.99

Types of cheese and antacid properties

Cheese, a beloved dairy product, is often scrutinized for its role in digestion, particularly in relation to acid reflux and heartburn. While it’s not classified as an antacid, certain types of cheese possess properties that may help neutralize stomach acid or alleviate discomfort. For instance, low-fat cheeses like mozzarella or cottage cheese are less likely to trigger acid production compared to high-fat varieties such as cheddar or blue cheese. Understanding the composition and acidity of different cheeses can guide individuals in making informed dietary choices to manage acid-related issues.

Analyzing the fat content is crucial when considering cheese as a potential antacid ally. High-fat cheeses slow down stomach emptying, increasing the likelihood of acid reflux. Conversely, low-fat options like ricotta or Swiss cheese are gentler on the stomach and may even provide a buffering effect due to their calcium content. Calcium carbonate, a common antacid ingredient, is naturally present in cheese, though in smaller amounts. Consuming 1–2 ounces of low-fat cheese after a meal could offer mild acid-neutralizing benefits without exacerbating symptoms.

For those seeking practical tips, pairing cheese with alkaline foods can enhance its antacid-like properties. For example, combining feta cheese with a spinach salad or enjoying fresh goat cheese with cucumber slices creates a balanced, acid-reducing snack. However, portion control is essential; excessive cheese intake, even of low-fat varieties, can still contribute to acidity. Limiting servings to 30–60 grams per sitting and avoiding cheese close to bedtime are recommended practices for acid reflux sufferers.

Comparatively, aged cheeses like Parmesan or Gouda have higher histamine levels, which can worsen acid reflux in sensitive individuals. Opting for fresher, milder cheeses such as cream cheese or paneer minimizes this risk. Additionally, fermented cheeses like cheddar contain probiotics that may support gut health, indirectly aiding in digestion and acid regulation. While not a substitute for traditional antacids, strategic cheese selection can complement dietary management of acid-related discomfort.

Instructively, individuals should monitor their body’s response to different cheeses to identify personal triggers. Keeping a food diary to track symptoms after consuming various types can provide valuable insights. For instance, if mozzarella consistently causes no issues, it could become a go-to option for acid-conscious snacking. Conversely, if blue cheese repeatedly leads to heartburn, it’s best avoided. Tailoring cheese choices to individual tolerance levels ensures enjoyment without compromising digestive comfort.

Discover the Perfect Cheese Pairing for Your Corned Beef Sandwich

You may want to see also

Cheese vs. traditional antacids

Cheese, a beloved dairy product, often finds itself at the center of debates about its health benefits and drawbacks. One intriguing question that arises is whether cheese can act as an antacid, providing relief from heartburn or acid reflux. Traditional antacids, such as Tums or Maalox, work by neutralizing stomach acid, but cheese operates differently. Its high fat and protein content can either alleviate or exacerbate symptoms depending on the individual and the type of cheese consumed. For instance, mild, low-fat cheeses like mozzarella or cottage cheese may soothe the stomach lining, while sharp, high-fat varieties like cheddar or blue cheese could trigger acid production.

Consider this scenario: a person experiences mild heartburn after a spicy meal. Instead of reaching for an antacid tablet, they opt for a small piece of mild cheese. The cheese’s calcium and protein content may help buffer stomach acid temporarily, providing modest relief. However, this approach lacks the precision of traditional antacids, which are formulated with specific doses of active ingredients like calcium carbonate or magnesium hydroxide. For example, a single Tums tablet contains 500 mg of calcium carbonate, offering quick and measurable acid neutralization. Cheese, on the other hand, lacks standardized dosing, making it an unreliable substitute for those seeking consistent relief.

From a persuasive standpoint, cheese could be marketed as a natural alternative to antacids, appealing to those wary of pharmaceutical interventions. Its nutritional benefits, including calcium and protein, add value beyond mere symptom relief. Yet, this argument falters when considering practical limitations. Traditional antacids act within minutes, whereas cheese’s effects are slower and less predictable. Additionally, individuals with lactose intolerance or dairy sensitivities may find cheese counterproductive, as it can stimulate acid production or cause bloating. For these groups, sticking to tried-and-true antacids is the safer choice.

A comparative analysis reveals another key difference: longevity of relief. Traditional antacids provide short-term relief but often require repeated doses, especially for chronic conditions. Cheese, while not a quick fix, may offer sustained benefits when incorporated into a balanced diet. For example, pairing a small portion of low-fat cheese with a meal can help neutralize acids over time, reducing the likelihood of post-meal discomfort. However, this strategy demands mindfulness about portion size and cheese type, as overconsumption can lead to the opposite effect.

In conclusion, while cheese may occasionally serve as a makeshift antacid, it cannot replace traditional remedies in terms of reliability and efficacy. For occasional, mild symptoms, a piece of mild, low-fat cheese might suffice, but for consistent, measurable relief, antacids remain the superior choice. Practical tips include opting for cheeses with lower fat content, monitoring portion sizes, and avoiding consumption close to bedtime to prevent nighttime reflux. Ultimately, the decision between cheese and antacids hinges on individual tolerance, symptom severity, and preference for natural versus pharmaceutical solutions.

Discover Hungry Howie's 3 Cheese Blend: Ingredients & Flavor Profile

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, cheese is not an antacid. Antacids are medications designed to neutralize stomach acid, while cheese is a dairy product.

Cheese can sometimes worsen acid reflux due to its high fat content, which can relax the lower esophageal sphincter and allow stomach acid to flow back up.

Cheese does not neutralize stomach acid. It lacks the alkaline properties found in antacids that help reduce acidity.

No, cheese is not a suitable alternative to antacids. It may even exacerbate symptoms of acidity or heartburn in some individuals.

Eating cheese is unlikely to reduce acidity in the stomach. In fact, its high fat and protein content may increase stomach acid production.