Cheese bark and cheese rind are often confused due to their similar appearance, but they are distinct components of cheese. The rind refers to the outer layer that forms naturally or is added during the aging process, serving as a protective barrier and influencing flavor and texture. Cheese bark, on the other hand, is a term sometimes used to describe the hardened, flavorful exterior of certain cheeses, particularly those that are aged or waxed. While both terms relate to the outer part of the cheese, the rind is a specific layer with a defined purpose, whereas cheese bark is more of a descriptive term for a textured, flavorful surface. Understanding the difference helps cheese enthusiasts appreciate the nuances of cheese production and aging.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Cheese bark refers to the hard, outer layer of certain aged cheeses, often formed during the aging process. Rind is a broader term for the outer layer of any cheese, which can be natural, bloomy, washed, or artificial. |

| Composition | Cheese bark is typically a hardened, dried, or crystallized part of the cheese surface. Rind can vary in texture and composition, ranging from soft and moldy (bloomy rind) to hard and waxy (natural rind). |

| Edibility | Cheese bark is often edible but may be too hard or flavor-intensive for some. Rind edibility varies; some rinds (e.g., Brie) are edible, while others (e.g., wax-coated rinds) are not. |

| Formation | Cheese bark forms naturally during aging due to drying or crystallization. Rind formation depends on the cheese type and aging process (e.g., mold growth, washing, or waxing). |

| Flavor | Cheese bark often concentrates the cheese's flavor, making it intense and umami-rich. Rind flavor varies; bloomy rinds add earthy notes, while washed rinds can be pungent. |

| Texture | Cheese bark is usually hard, brittle, or crystalline. Rind texture ranges from soft and creamy (bloomy) to firm and waxy (natural). |

| Purpose | Cheese bark protects the cheese and enhances flavor. Rind serves as a protective layer, influences flavor, and supports aging. |

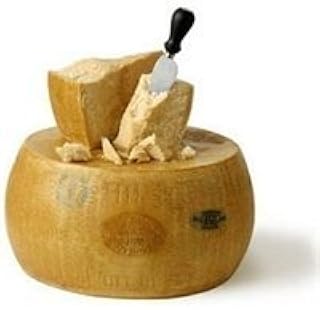

| Examples | Parmigiano-Reggiano has a hard, granular bark. Brie has a bloomy, edible rind. |

| Interchangeability | Cheese bark is a specific type of rind, but not all rinds are bark. The terms are related but not synonymous. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Cheese Bark: Cheese bark refers to the hard, outer layer formed during aging, often confused with rind

- Rind vs. Bark Texture: Rinds are typically softer or moldy, while bark is dry, brittle, and crust-like

- Formation Process: Bark forms from air-dried surfaces; rinds develop from bacteria, mold, or wax coatings

- Edibility Differences: Most rinds are edible, but bark is usually too tough and removed before consumption

- Cheese Types: Bark is common in aged cheeses like Parmesan; rinds vary across types (e.g., Brie, Gouda)

Definition of Cheese Bark: Cheese bark refers to the hard, outer layer formed during aging, often confused with rind

Cheese bark, a term that might sound unfamiliar to many, is a distinct feature of certain aged cheeses. It refers specifically to the hard, outer layer that develops during the aging process, often mistaken for the rind. This layer is not merely a protective barrier but a complex structure that contributes to the cheese's flavor, texture, and overall character. Unlike the rind, which can be intentionally cultivated through mold or bacteria, cheese bark forms naturally as a result of moisture loss and the concentration of salts and proteins on the surface. Understanding this distinction is crucial for both cheese enthusiasts and artisans, as it influences how the cheese is handled, stored, and ultimately enjoyed.

To appreciate the role of cheese bark, consider the aging process of hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano or aged Gouda. As these cheeses mature, the exterior dries out, creating a tough, crystalline layer that acts as a shield against external elements. This bark is not meant to be eaten but rather serves as a testament to the cheese’s longevity and craftsmanship. In contrast, the rind—whether natural, washed, or bloomed—is often edible and plays a different role in flavor development. For instance, a bloomy rind on Brie contributes creamy, earthy notes, while a washed rind on Epoisses adds pungency. Cheese bark, however, is purely structural, though its presence can subtly influence the cheese’s internal flavor profile by regulating moisture loss.

For those aging cheese at home, recognizing cheese bark is essential for proper care. Unlike rinds that may require regular washing or flipping, cheese bark should be left undisturbed to maintain its integrity. If the bark cracks or becomes damaged, the cheese is at risk of drying out unevenly or developing unwanted molds. To prevent this, store aged cheeses in a cool, humid environment, ideally at 50–55°F (10–13°C) with 80–85% humidity. Wrapping the cheese in waxed paper or cheesecloth allows it to breathe while protecting the bark. Regularly inspect the bark for signs of excessive drying or mold, and trim any affected areas carefully to preserve the cheese’s quality.

A common misconception is that cheese bark and rind are interchangeable terms, but their functions and compositions differ significantly. While both are external layers, the rind is often a living component, hosting microorganisms that contribute to flavor and texture. Cheese bark, on the other hand, is inert—a hardened residue of the aging process. This distinction matters when selecting or serving cheese. For example, a cheese with a pronounced bark may require more effort to cut through, whereas a rind might be peeled back to reveal a softer interior. By understanding these differences, consumers can better appreciate the nuances of each cheese and make informed choices.

In culinary applications, cheese bark is rarely utilized directly, but its presence can enhance the overall experience of aged cheeses. When serving a cheese with a well-developed bark, present it alongside tools like a cheese plane or heavy-duty knife to facilitate slicing. Encourage guests to taste the cheese’s interior, where the bark’s influence on moisture and flavor concentration is most evident. For recipes requiring grated or melted cheese, remove the bark entirely, as its hardness can detract from the desired texture. By respecting the bark’s role, you elevate the cheese’s natural qualities, turning a simple dish into a celebration of craftsmanship and time.

Unveiling the McDouble Mystery: Cheese Slices Count Explained

You may want to see also

Rind vs. Bark Texture: Rinds are typically softer or moldy, while bark is dry, brittle, and crust-like

Cheese enthusiasts often confuse the terms "bark" and "rind," but a closer look at their textures reveals distinct differences. Rinds, whether natural or bloomy, tend to be softer, sometimes even moldy, due to the growth of bacteria or fungi during aging. This softness can range from a velvety touch in Camembert to a slightly tacky surface in Brie. In contrast, cheese bark presents a dry, brittle, and crust-like texture, often resembling the exterior of a tree. This bark forms through a different aging process, typically involving dehydration or the application of specific molds that create a harder, more fragmented surface.

To appreciate these differences, consider the sensory experience. When you handle a cheese with a rind, you’ll notice it yields slightly under pressure, especially in younger varieties. For instance, a young Gouda’s rind is pliable and almost waxy. Cheese bark, however, offers no such give. It’s rigid, often cracking when cut or broken, much like the bark of a tree. This brittleness is a hallmark of bark, making it both a textural contrast and a protective layer that preserves the cheese beneath.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these textures can guide your cheese selection and preparation. Soft, moldy rinds are ideal for spreading on crackers or melting into dishes, as they integrate seamlessly. Cheese bark, with its dry and crust-like nature, is better suited for grating or using as a garnish, adding a crunchy element to dishes. For example, the bark of a Parmigiano-Reggiano can be finely grated over pasta, while its softer rind might be discarded or used in soups for added flavor.

Aging processes play a critical role in these textural differences. Rinds often develop through surface bacteria or mold cultivation, which thrive in moist environments, leading to their softer, sometimes sticky consistency. Bark, on the other hand, forms in drier conditions, where moisture evaporates, leaving behind a hardened exterior. This distinction is particularly evident in aged cheeses like Cheddar, where the bark becomes increasingly brittle over time, while the rind remains relatively supple.

In conclusion, while both bark and rind serve as protective layers, their textures diverge significantly. Rinds are softer or moldy, offering a sensory experience that’s both tactile and flavorful. Bark, with its dry, brittle, and crust-like nature, provides a contrasting crunch and durability. Recognizing these differences not only enhances your cheese knowledge but also elevates your culinary applications, ensuring you use each type to its fullest potential.

Mastering Elden Ring: Cheesing Loretta, Knight of the Haligtree

You may want to see also

Formation Process: Bark forms from air-dried surfaces; rinds develop from bacteria, mold, or wax coatings

Cheese bark and rind, though often confused, arise from fundamentally different processes. Bark forms through air-drying, where the cheese’s exterior hardens as moisture evaporates, creating a dry, brittle layer. This method relies on controlled exposure to air, typically in aging rooms with regulated humidity and temperature. For example, Parmigiano-Reggiano develops a natural bark during its long aging period, which is then trimmed before consumption. In contrast, rinds are cultivated through intentional bacterial, mold, or wax applications. Bacteria and mold, such as *Penicillium camemberti* in Camembert, grow on the cheese surface, creating a soft, edible rind. Wax coatings, like those on Gouda, act as a protective barrier, influencing moisture retention and flavor development.

To create a bark, cheesemakers follow a precise air-drying regimen. The cheese is placed in well-ventilated environments, often on wooden shelves, where air circulates freely around it. Humidity levels are kept low (around 60-70%) to encourage moisture loss without causing cracking. Temperature is maintained between 50-59°F (10-15°C) to slow the drying process, ensuring the bark forms evenly. For home cheesemakers, mimicking this requires a cool, dry space with a fan for airflow. Avoid plastic containers, as they trap moisture, and instead use breathable materials like cheese mats.

Rind development, however, is a more hands-on process. Bacterial and mold rinds require inoculation with specific cultures, often sprayed or sprinkled onto the cheese surface. For instance, Brie’s signature white rind comes from *Geotrichum candidum* and *Penicillium camemberti*, which are applied during the first 24 hours of aging. Wax rinds involve brushing or dipping the cheese in food-grade wax, typically at 160-180°F (71-82°C) to ensure even coverage. This method is ideal for cheeses like Cheddar, where moisture control is critical. Caution: improper wax application can lead to uneven rinds or trapped bacteria, so use a double-boiler to maintain consistent temperature.

The distinction between bark and rind has practical implications for cheese consumption and storage. Bark, being air-dried, is often too tough to eat and is removed before serving. Rinds, however, are frequently edible, adding texture and flavor. For example, the bloomy rind of Camembert is a delicacy, while the wax rind of Gouda is inedible but preserves the cheese. When storing barked cheeses, wrap them in parchment paper to allow breathability, whereas waxed cheeses can be stored in airtight containers to prevent drying.

Understanding these formation processes empowers both cheesemakers and enthusiasts to appreciate the craft behind each cheese. Bark represents a natural, passive transformation, while rinds showcase intentional microbial or protective interventions. Whether you’re aging a wheel in your basement or selecting cheese at a market, recognizing these differences ensures you handle and enjoy each variety to its fullest potential.

Cheese Skin Unveiled: Understanding the Rind's Role and Names

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Edibility Differences: Most rinds are edible, but bark is usually too tough and removed before consumption

Cheese enthusiasts often encounter a textural dilemma: the outer layer. While both bark and rind describe the exterior of cheese, their edibility differs significantly. Rinds, typically developed through aging and microbial action, are usually edible and contribute to flavor and texture. Bark, however, refers to a thicker, tougher outer layer, often formed during pressing or aging, which is generally removed before consumption due to its unpalatable texture.

Consider the aging process of cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano or Gouda. Their rinds, though hard, are edible and often grated or melted for added flavor. In contrast, the bark of cheeses like Cheddar or Colby is a byproduct of the pressing process, creating a dense, rubbery layer that lacks flavor and is difficult to chew. Removing this bark ensures a more enjoyable eating experience, allowing the cheese’s interior qualities to shine.

For home cooks, distinguishing between rind and bark is crucial. Rinds can be incorporated into recipes—think baked Brie with its rind intact or grated aged cheese for soups. Bark, however, should be discarded. When purchasing cheese, inspect the outer layer: if it’s smooth, thin, and integrates with the cheese, it’s likely a rind. If it’s thick, dry, and peels away easily, treat it as bark and remove it before serving.

Practical tip: For cheeses with bark, use a sharp knife to carefully trim the outer layer, preserving as much of the interior as possible. For rinds, experiment with cooking methods—roasting or melting can enhance their texture and flavor. Understanding these differences not only elevates your cheese experience but also minimizes waste, ensuring every bite is as intended.

Perfect Cheesecake: Signs It's Done and Ready to Enjoy

You may want to see also

Cheese Types: Bark is common in aged cheeses like Parmesan; rinds vary across types (e.g., Brie, Gouda)

Cheese bark, often confused with the rind, is a distinct feature primarily found in aged cheeses like Parmesan. This hard, outer layer forms during the aging process as the cheese dries and hardens, creating a protective barrier that concentrates flavor. Unlike the rind, which can be soft, bloomy, or washed depending on the cheese type, bark is consistently tough and inedible. It serves as a natural shield, allowing the interior to mature without spoiling. For instance, Parmesan’s bark is a hallmark of its long aging process, typically 12 to 36 months, which intensifies its nutty, umami-rich profile.

To distinguish bark from rind, consider texture and purpose. Rinds are diverse: Brie’s white, velvety exterior is a bloomy rind, cultivated from Penicillium camemberti mold, while Gouda’s waxed rind is designed to slow moisture loss. Bark, however, is not a cultivated layer but a result of dehydration and crystallization of fats and proteins. It’s why you’ll never eat Parmesan’s bark but might savor the rind of a washed-rind cheese like Époisses. Understanding this difference helps in selecting and preparing cheese—for example, removing bark before grating Parmesan ensures a smoother texture.

Aged cheeses with bark, like Parmesan or Grana Padano, are staples in culinary applications requiring intense flavor. A practical tip: save Parmesan bark to infuse broths or sauces. Its porous structure releases savory notes when simmered, enhancing dishes like risotto or minestrone. Conversely, rinds like those of Brie or Camembert are often edible and contribute to the cheese’s overall character. Pairing Brie with a crisp apple or honey highlights its creamy interior and contrasts its earthy rind.

The variation in rinds across cheese types reflects their production methods. Gouda’s waxed rind preserves its semi-hard texture, while the washed rind of Taleggio develops a pungent aroma from brine or wine baths. Bark, however, is a passive outcome of aging, not a deliberate addition. This distinction matters for storage: aged cheeses with bark can last months in a cool, dry place, whereas soft-rind cheeses like Brie require refrigeration and consume within weeks. Knowing these differences ensures optimal use and enjoyment of each cheese type.

In summary, while bark and rind are both outer layers, they serve different roles and appear in distinct cheese categories. Bark is exclusive to aged, hard cheeses like Parmesan, acting as a natural preservative, while rinds vary widely across types, from bloomy to washed. Recognizing these features not only deepens appreciation for cheese craftsmanship but also guides practical decisions in cooking and storage. Whether grating Parmesan or savoring Brie, understanding these nuances elevates the cheese experience.

Does the Original Philly Cheesesteak Always Include Cheese?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, cheese bark is another term for the rind of certain aged or hard cheeses, especially when it develops a hard, crusty, or textured exterior.

Cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano, aged Gouda, and Alpine-style cheeses often develop a hard, bark-like rind during the aging process.

While cheese bark is technically edible, it is often tough, bitter, or unpalatable, so it is usually removed or discarded before eating.

Yes, the bark plays a crucial role in protecting the cheese during aging and can contribute to its flavor development, though it is not typically consumed.

Yes, cheese bark can be used to add flavor to soups, stews, or sauces, similar to how Parmesan rinds are used, but it is not eaten directly.