The claim that cheese contains cow pus is a topic of debate and often stems from the presence of somatic cells in milk, which are commonly referred to as pus cells. These cells are naturally present in the udders of cows and can increase in number due to factors like mastitis (udder inflammation) or poor milking practices. While it’s true that milk used for cheese production may contain some somatic cells, the levels are typically regulated and monitored to ensure they remain within safe limits. The term pus is misleading, as somatic cells are not pus in the medical sense but rather a natural component of milk. Cheese production involves processes like pasteurization and culturing, which further reduce or eliminate any potential contaminants. Therefore, while cheese may technically contain trace amounts of somatic cells, it is inaccurate and alarmist to label it as cow pus.

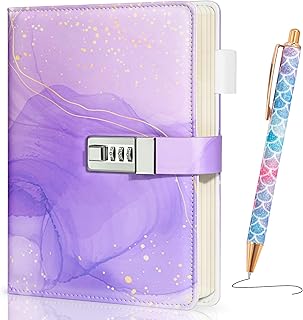

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Myth vs. Reality: Clarifying misconceptions about cheese production and cow health

- Pus in Milk: Investigating claims of somatic cells in dairy products

- Cheese-Making Process: How milk is transformed into cheese, step-by-step

- Dairy Industry Standards: Regulations ensuring milk and cheese safety and quality

- Health Implications: Examining if consuming cheese affects human health based on its origin

Myth vs. Reality: Clarifying misconceptions about cheese production and cow health

Cheese production often faces scrutiny due to the myth that it contains cow pus, a claim rooted in the presence of somatic cells in milk. Somatic cells, primarily white blood cells, naturally occur in milk as part of a cow’s immune response to minor udder infections or inflammation. While high somatic cell counts (SCC) can indicate poor cow health, regulatory standards strictly limit acceptable levels. For example, the FDA allows up to 750,000 cells per milliliter in milk for human consumption, a threshold well below levels considered harmful. Milk exceeding this limit is discarded, ensuring that cheese and dairy products are safe and free from significant contaminants.

To understand the reality, consider the process of cheese making. Milk is pasteurized at temperatures between 160°F and 280°F (71°C to 138°C), a step that eliminates bacteria, somatic cells, and potential pathogens. Even raw milk cheeses, which bypass pasteurization, must adhere to strict hygiene practices to prevent contamination. Additionally, somatic cells do not survive the cheese-making process; they are broken down during curdling and aging, leaving no trace of pus in the final product. This scientific approach debunks the myth, emphasizing that cheese is a product of milk’s proteins and fats, not its cellular components.

A comparative analysis of somatic cells in milk versus pus reveals stark differences. Pus, a thick, viscous substance, contains dead tissue, bacteria, and immune cells in far greater concentrations than milk. For instance, infected wounds can have billions of somatic cells per milliliter, compared to the regulated maximum of 750,000 in milk. This disparity highlights the inaccuracy of equating somatic cells in milk with pus. Furthermore, dairy farmers prioritize cow health through regular veterinary check-ups, balanced diets, and clean milking environments, reducing the likelihood of high SCC. Healthy cows produce milk with minimal somatic cells, ensuring the integrity of dairy products.

Persuasively, the myth of cheese containing cow pus undermines consumer trust in dairy farming and cheese production. Education is key to dispelling this misconception. Consumers should seek reliable sources, such as peer-reviewed studies or agricultural organizations, to understand dairy practices. Practical tips include checking labels for certifications like “organic” or “grass-fed,” which often indicate higher animal welfare standards. Visiting local dairies or attending cheese-making workshops can also provide firsthand insight into the care and precision involved. By separating myth from reality, individuals can make informed choices and appreciate cheese as a product of science, tradition, and animal husbandry.

Does Nacho Cheese Contain Dairy? Unraveling the Cheesy Mystery

You may want to see also

Pus in Milk: Investigating claims of somatic cells in dairy products

The presence of somatic cells in milk, often colloquially referred to as "cow pus," has sparked considerable debate among consumers, health advocates, and dairy industry professionals. Somatic cells, primarily white blood cells, naturally occur in milk as part of a cow’s immune response to infections like mastitis. While their presence is unavoidable, high levels can indicate poor animal health or hygiene practices. Regulatory bodies, such as the FDA, set limits for somatic cell counts (SCC) in milk—typically 750,000 cells/mL or lower—to ensure product safety and quality. Exceeding these thresholds can lead to milk rejection or penalties for producers.

To investigate claims of somatic cells in dairy products, start by understanding the testing process. Dairies routinely use tools like the somatic cell count (SCC) test to monitor milk quality. For consumers, checking labels for certifications like "low SCC" or "organic" can provide assurance, as these products often adhere to stricter standards. However, it’s important to note that somatic cells are not inherently harmful in low quantities. They are denatured during pasteurization, rendering them biologically inert. The real concern arises when high SCC levels correlate with bacterial contamination or animal welfare issues.

From a health perspective, the debate over somatic cells often conflates their presence with pus, a misleading comparison. Pus contains dead tissue, bacteria, and white blood cells, whereas milk with elevated SCC contains primarily live white blood cells. While excessive consumption of high-SCC milk may pose risks for individuals with dairy sensitivities, there is no scientific evidence linking moderate intake to adverse health effects in the general population. For those concerned, opting for plant-based alternatives or dairy products from grass-fed, well-managed herds can mitigate exposure.

Practically, reducing somatic cell counts in dairy production benefits both farmers and consumers. Farmers can implement strategies like regular udder hygiene, proper milking techniques, and prompt treatment of mastitis. Consumers can support ethical practices by choosing brands that prioritize animal welfare and transparency. For instance, European organic standards mandate SCC levels below 400,000 cells/mL, significantly lower than conventional limits. By educating themselves and making informed choices, consumers can navigate the "pus in milk" debate with clarity and confidence.

Does Brie Cheese Contain Nuts? A Comprehensive Guide for Cheese Lovers

You may want to see also

Cheese-Making Process: How milk is transformed into cheese, step-by-step

The claim that cheese contains cow pus often stems from the presence of somatic cells in milk, which can include white blood cells. However, these cells are a natural part of milk composition and are not indicative of infection or pus. Understanding the cheese-making process clarifies how milk is transformed into cheese, dispelling misconceptions about its ingredients.

Step 1: Milk Selection and Preparation

Cheese production begins with high-quality milk, typically from cows, goats, or sheep. The milk is first tested for somatic cell count (SCC), which should ideally be below 200,000 cells/mL for optimal cheese quality. Raw or pasteurized milk can be used, though pasteurization is common to eliminate pathogens. The milk is then heated to specific temperatures (e.g., 30°C for soft cheeses, 35°C for hard cheeses) to prepare it for coagulation.

Step 2: Coagulation and Curdling

Coagulation is achieved by adding rennet or microbial enzymes to the milk, causing it to curdle. This process separates the milk into curds (solid) and whey (liquid). The curds are the foundation of cheese and contain proteins, fats, and minimal somatic cells. The whey, which holds most of the lactose and water, is often discarded or used in other products.

Step 3: Cutting, Cooking, and Draining

The curds are cut into smaller pieces to release more whey. For hard cheeses, the curds are heated (cooked) to expel additional moisture and firm up the texture. This step is skipped for soft cheeses. The curds are then drained and pressed to remove excess whey, shaping them into the desired form.

Step 4: Salting, Molding, and Aging

Salt is added to the curds to enhance flavor and preserve the cheese. The cheese is then molded and pressed further to achieve its final shape. Aging (ripening) follows, during which bacteria and molds transform the cheese’s texture and taste. Aging times vary: 2–4 weeks for fresh cheeses, 2–12 months for hard cheeses like cheddar, and up to 2 years for parmesan.

Cautions and Clarifications

While somatic cells are present in milk, they are not pus. Pus is a product of infection, containing dead tissue and pathogens, which is not allowed in dairy production. Regulatory standards ensure milk used for cheese is free from infected sources. High SCC levels can indicate poor animal health, but these cases are typically excluded from cheese production.

The cheese-making process is a meticulous transformation of milk into a diverse array of cheeses. From coagulation to aging, each step refines the product, ensuring quality and safety. Understanding this process highlights the natural origins of cheese and debunks the myth of it containing cow pus.

Cool Ranch vs. Nacho Cheese: Which Doritos Flavor Came First?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dairy Industry Standards: Regulations ensuring milk and cheese safety and quality

The claim that cheese contains cow pus often stems from the presence of somatic cells—primarily white blood cells—in milk. These cells naturally increase in response to mastitis, an inflammation of the udder, but their presence alone does not equate to pus. Dairy industry standards strictly regulate somatic cell counts (SCC) to ensure milk and cheese safety. The FDA limits SCC to 750,000 cells/mL in milk, a threshold well below levels considered harmful. Exceeding this limit triggers penalties for producers, incentivizing proactive herd health management. While high SCC can indicate poor hygiene or animal health issues, regulated counts ensure that milk used for cheese production remains safe and free from contamination.

To maintain quality, dairy producers follow a multi-step process that begins with milking hygiene. Teat dipping, equipment sanitization, and regular udder inspections are mandatory practices. Milk is then rapidly cooled to 4°C (39°F) to inhibit bacterial growth before transport to processing facilities. During cheese production, pasteurization further eliminates pathogens, though artisanal cheeses may use raw milk under strict guidelines. For instance, the EU requires raw milk cheeses to mature for at least 60 days at 3°C (37°F) to reduce pathogen risks. These steps collectively ensure that somatic cells, even if present, do not compromise product safety.

Regulations also address consumer concerns by mandating transparency and labeling. In the U.S., cheese made from milk exceeding SCC limits must be labeled as "manufactured milk," distinguishing it from higher-quality products. Organic dairy standards are even stricter, capping SCC at 400,000 cells/mL and prohibiting antibiotics in animal treatment. Such measures not only safeguard health but also build trust in the industry. Consumers can look for certifications like "USDA Organic" or "Animal Welfare Approved" to ensure adherence to rigorous standards.

Comparatively, global dairy regulations vary, but the goal remains consistent: protecting public health. The EU’s SCC limit is 400,000 cells/mL, tighter than the U.S. standard, reflecting differing priorities in animal welfare and product quality. Canada enforces a "Bacteriological Letter Grade" system, penalizing dairies with high bacterial counts. These variations highlight the importance of context when evaluating claims about dairy safety. Regardless of region, compliance with local standards ensures that cheese remains a safe, high-quality food product.

Practical tips for consumers include checking labels for certifications and understanding that somatic cells are not inherently harmful at regulated levels. For those concerned about animal welfare, supporting dairies with lower SCC counts or organic certifications can align purchases with personal values. Ultimately, dairy industry standards serve as a robust framework, ensuring that cheese production meets safety and quality benchmarks while addressing misconceptions about milk composition.

Is the Bacon Egg and Cheese Bagel Back? Find Out Now!

You may want to see also

Health Implications: Examining if consuming cheese affects human health based on its origin

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, often sparks debates about its health implications, particularly when claims of it containing cow pus surface. To address this, it’s essential to understand that cheese is primarily made from milk, which can contain somatic cells—a natural part of milk production. These cells, often misrepresented as "pus," are present in trace amounts and do not inherently render cheese unhealthy. However, the origin of the milk and the conditions under which it is produced play a critical role in determining potential health impacts. For instance, milk from cows raised in unsanitary conditions or under high stress may have elevated somatic cell counts, which could introduce bacteria or inflammatory markers into the cheese.

Analyzing the health implications requires a nuanced approach. While somatic cells themselves are not harmful in small quantities, their presence can indicate poor animal health or hygiene practices. Consuming cheese from such sources may expose individuals to pathogens or toxins, potentially leading to gastrointestinal issues or allergic reactions. For example, individuals with lactose intolerance or dairy allergies may experience exacerbated symptoms when consuming cheese from low-quality milk. Additionally, the aging process of cheese can reduce certain risks by eliminating harmful bacteria, but this is not a guarantee. Practical advice for consumers includes opting for cheese made from organic, pasture-raised cows, as these animals typically produce milk with lower somatic cell counts and fewer contaminants.

From a comparative perspective, the health effects of cheese vary significantly based on its origin and production methods. Artisanal cheeses made from raw milk, for instance, retain beneficial probiotics that can support gut health, whereas mass-produced cheeses may contain additives or preservatives that negate these benefits. Studies suggest that moderate consumption of high-quality cheese can contribute to bone health due to its calcium and vitamin K2 content. However, cheese from cows treated with hormones or antibiotics may introduce residues into the product, potentially disrupting human hormonal balance or contributing to antibiotic resistance. To mitigate these risks, consumers should prioritize transparency in sourcing and look for certifications like "organic" or "grass-fed."

Persuasively, the argument for mindful cheese consumption hinges on informed choices. For families, especially those with children or elderly members, selecting cheese from reputable sources is crucial. A practical tip is to read labels carefully and avoid products with artificial additives or unclear origins. For instance, a 30g serving of high-quality cheese daily can provide nutritional benefits without adverse effects, whereas frequent consumption of low-quality cheese may pose health risks over time. Age-specific considerations include limiting processed cheese for children due to its high sodium content and opting for softer, easier-to-digest varieties for older adults.

In conclusion, the health implications of consuming cheese are deeply tied to its origin and production practices. While somatic cells in milk are not inherently harmful, their presence can signal underlying issues that impact cheese quality. By choosing cheese from well-managed, ethical sources and understanding its nutritional profile, individuals can enjoy this dairy product while minimizing potential health risks. This approach not only supports personal well-being but also promotes sustainable and humane agricultural practices.

Why Milk and Cheese Are Always at the Back of Stores

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, cheese is not made from cow pus. Cheese is primarily made from milk, which is processed through coagulation and fermentation. Cow pus, which is associated with mastitis (an infection in the udder), is not used in cheese production.

Cheese does not contain pus from cows. While milk from cows with mastitis may contain somatic cells (including white blood cells), reputable dairy producers ensure that milk is tested and discarded if it shows signs of infection. Commercial cheese is made from healthy milk.

It is not true that cheese has cow pus in it. The claim often stems from a misunderstanding of somatic cells in milk. While milk can contain these cells, they are not pus, and strict regulations prevent contaminated milk from being used in cheese production.