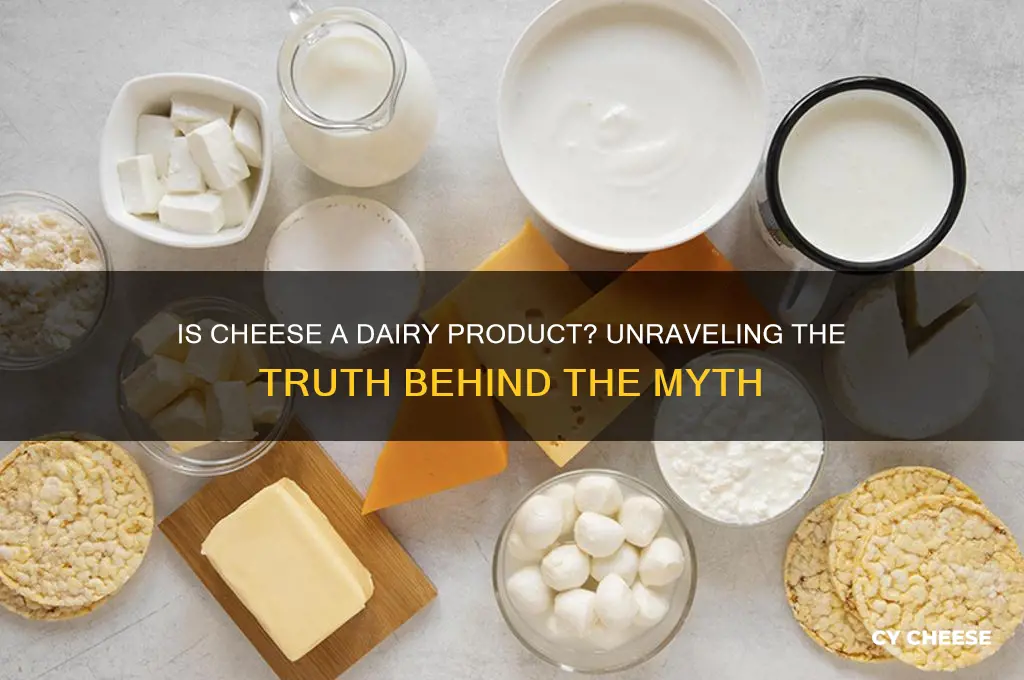

The question Is cheese dairy? often arises due to its origins and composition. Cheese is indeed a dairy product, as it is made from milk, typically from cows, goats, or sheep. The process involves curdling milk, usually with the help of bacteria or enzymes, and then separating the solid curds from the liquid whey. Despite undergoing significant transformations during production, cheese retains its dairy classification because its primary ingredient is milk. This distinction is important for dietary considerations, as individuals with lactose intolerance or dairy allergies need to be aware of cheese’s dairy content, even though some types may contain lower levels of lactose.

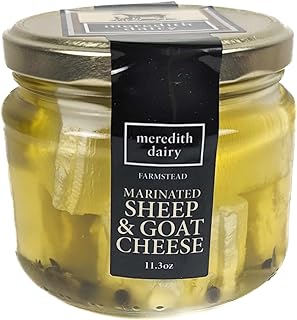

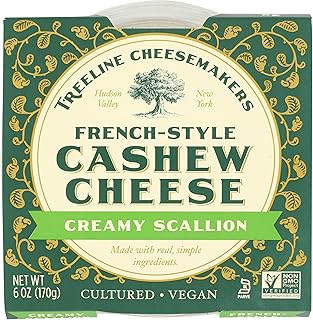

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Cheese vs. Dairy Definition

Cheese is a dairy product, but not all dairy is cheese. This distinction is crucial for dietary choices, especially for those with lactose intolerance or dairy allergies. Dairy refers to any food product made from milk, including butter, yogurt, and ice cream. Cheese, however, is a specific type of dairy that undergoes a transformation process involving curdling, draining, and aging. Understanding this difference helps in making informed decisions about nutrition and ingredient substitutions.

Analyzing the production process reveals why cheese stands apart from other dairy products. While milk, cream, and butter are relatively simple derivatives of milk, cheese requires additional steps such as coagulation, pressing, and fermentation. For example, cheddar cheese ages for 60 days to several years, developing its distinct texture and flavor. This complexity not only alters its nutritional profile—increasing protein and fat content—but also reduces lactose levels, making it more tolerable for some lactose-intolerant individuals.

From a dietary perspective, cheese and dairy serve different roles. Dairy products like milk are often consumed for their calcium and vitamin D content, essential for bone health. Cheese, while also calcium-rich, is denser in calories and fat, making portion control important. A 1-ounce serving of cheddar provides about 115 calories and 7 grams of protein, compared to 8 grams of protein in 8 ounces of milk. For those monitoring fat intake, opting for low-fat dairy over cheese can be a strategic choice, though cheese offers unique satiety benefits due to its protein and fat combination.

Practical tips for distinguishing between cheese and dairy in recipes are invaluable. Substituting cheese for dairy (or vice versa) requires consideration of texture and moisture content. For instance, replacing milk with cheese in a sauce will thicken it significantly, while using dairy in place of cheese in a salad may dilute flavors. A useful rule of thumb: when substituting, balance moisture by adding liquid (like milk) if using cheese, or thickening agents (like flour) if using dairy. Always account for lactose content, especially in baked goods, where cheese’s lower lactose levels may affect leavening.

In conclusion, while cheese is undeniably dairy, its unique production and nutritional characteristics set it apart. Recognizing this distinction empowers individuals to tailor their diets effectively, whether for health, culinary, or lifestyle reasons. By understanding the specific roles of cheese and dairy, one can make smarter choices in both the kitchen and at the grocery store.

Does Cheese Contain Algae? Unraveling the Surprising Dairy Mystery

You may want to see also

Cheese Production Process

Cheese production is a fascinating blend of science and art, transforming milk into a diverse array of flavors, textures, and aromas. At its core, the process begins with milk—cow, goat, sheep, or even buffalo—which is first tested for quality and standardized for fat content. Raw milk is often pasteurized at 72°C (161°F) for 15 seconds to eliminate harmful bacteria while preserving beneficial enzymes, though some artisanal cheeses use raw milk for added complexity. This initial step sets the stage for the intricate journey from liquid to solid.

The next critical phase is coagulation, where milk is transformed into curds and whey. Rennet, a complex of enzymes, is added to the warmed milk (typically 30–35°C or 86–95°F) at a precise dosage—about 0.02–0.05% of the milk volume. This causes the milk to curdle within 30–60 minutes, depending on the type of cheese. For vegetarian alternatives, microbial transglutaminase or plant-based coagulants like fig tree bark extract can be used. Cutting the curd follows, a step that releases whey and determines the cheese’s final texture. Soft cheeses like mozzarella are cut loosely, while hard cheeses like cheddar are cut finely to expel more whey.

After cutting, the curds are heated and stirred in a process called scalding, which further expels whey and develops acidity. Temperature control is crucial here—for cheddar, curds are heated to 39–40°C (102–104°F), while for Swiss cheese, temperatures reach 46–49°C (115–120°F). Salting is then applied either directly to the curds or through brine baths, preserving the cheese and enhancing flavor. The curds are then pressed into molds to remove excess whey and form the cheese’s shape. This step varies widely: fresh cheeses like ricotta are lightly drained, while hard cheeses like Parmesan are pressed under heavy weights for hours.

Aging, or ripening, is where cheese develops its distinctive character. During this stage, controlled environments (temperature, humidity, and airflow) allow bacteria and molds to transform the cheese. For example, blue cheese is pierced with needles to allow air in, fostering the growth of Penicillium mold. Hard cheeses age for months or even years, while soft cheeses may ripen in just a few weeks. Proper storage is key—hard cheeses should be wrapped in wax paper and stored at 10–13°C (50–55°F), while soft cheeses require higher humidity to prevent drying.

Finally, the cheese is ready for consumption, but not without a few practical tips. Always bring cheese to room temperature before serving to unlock its full flavor profile. Pairing cheese with the right accompaniments—such as honey for blue cheese or nuts for aged cheddar—can elevate the experience. For home cheesemakers, start with simple recipes like paneer or ricotta, which require minimal equipment and offer immediate gratification. Understanding the production process not only deepens appreciation for this ancient craft but also empowers experimentation and innovation in the kitchen.

Does Chipotle Offer Nacho Cheese? Exploring the Menu Options

You may want to see also

Nutritional Differences

Cheese and dairy are often lumped together, but their nutritional profiles diverge significantly, particularly in protein, fat, and lactose content. A 30-gram serving of cheddar cheese, for instance, contains about 7 grams of protein, while the same volume of whole milk provides only 2 grams. This disparity makes cheese a more concentrated protein source, ideal for muscle repair and satiety. However, cheese’s fat content is higher—cheddar has 6 grams of fat per serving, compared to 3 grams in whole milk. For those monitoring fat intake, this distinction is critical. Additionally, cheese undergoes a fermentation process that breaks down lactose, making it a viable option for individuals with mild lactose intolerance. Dairy milk, in contrast, retains its lactose, potentially causing digestive discomfort for sensitive individuals.

Consider calcium and vitamin D, two nutrients essential for bone health. Dairy milk is often fortified with vitamin D, providing up to 25% of the daily recommended intake per cup (240 ml). Cheese, while naturally rich in calcium (cheddar offers 300 mg per 30-gram serving), rarely contains added vitamin D. This makes dairy milk a more comprehensive option for those seeking both nutrients in one source. However, aged cheeses like Parmesan deliver calcium in a more compact form—31 grams of Parmesan provides 330 mg of calcium, equivalent to a full glass of milk. For older adults or those with limited dietary variety, cheese can be a practical alternative to meet calcium needs without consuming large volumes of liquid dairy.

The sodium content in cheese is another nutritional difference that warrants attention. A single ounce of feta cheese contains 310 mg of sodium, while the same amount of mozzarella has 170 mg. Dairy milk, on the other hand, contains negligible sodium. For individuals with hypertension or those following a low-sodium diet, this distinction is vital. Pairing cheese with potassium-rich foods like spinach or bananas can help mitigate sodium’s impact on blood pressure. Alternatively, opting for lower-sodium cheeses like fresh mozzarella or Swiss can provide a middle ground for cheese lovers.

From a calorie perspective, cheese is more energy-dense than dairy milk. One cup of whole milk contains 150 calories, whereas 30 grams of Gouda cheese packs 100 calories. This density can be advantageous for those needing quick energy or calorie-rich diets, such as athletes or individuals with high metabolic rates. However, it also poses a risk for overconsumption, particularly in snack scenarios. Portion control is key—pre-measuring cheese servings (e.g., 20-30 grams) can prevent unintentional calorie surplus. For children and adolescents, cheese’s calorie and nutrient density supports growth, but moderation is essential to avoid excessive fat intake.

Finally, the vitamin B12 content in cheese and dairy highlights another nutritional divergence. Dairy milk provides 1.2 micrograms of B12 per cup, meeting 50% of the daily requirement for adults. Cheese, while not as rich, still contributes meaningfully—30 grams of Swiss cheese offers 0.9 micrograms. This vitamin is crucial for nerve function and DNA synthesis, making both dairy and cheese valuable for vegetarians or those at risk of deficiency. However, dairy milk’s liquid form allows for easier integration into meals (e.g., smoothies, cereals), while cheese’s versatility as a topping or snack ensures B12 intake in varied dietary patterns. Tailoring choices based on lifestyle and dietary needs maximizes the benefits of each.

Mastering Maroilles Cheese: A Step-by-Step Homemade Recipe Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Lactose Content in Cheese

Cheese, a beloved staple in many diets, often raises questions about its lactose content, especially for those with dairy sensitivities. Contrary to popular belief, not all cheeses are created equal when it comes to lactose. Hard cheeses like cheddar, Parmesan, and Swiss undergo a longer aging process, which naturally reduces their lactose levels to nearly zero. This makes them a safer option for individuals with lactose intolerance. For example, a 30-gram serving of cheddar contains less than 0.03 grams of lactose, compared to the 10 grams found in an equivalent serving of milk. Understanding these differences can empower you to enjoy cheese without discomfort.

For those with mild lactose intolerance, semi-soft cheeses like mozzarella or provolone can be a middle ground. These cheeses retain slightly more lactose—around 0.5 to 1 gram per serving—but are still manageable for many. Pairing these cheeses with lactase enzymes or consuming them in smaller portions can further minimize digestive issues. It’s also worth noting that fermented cheeses like Gouda or Edam have lower lactose due to bacterial activity during production, making them another viable option.

If you’re highly sensitive to lactose, opt for lactose-free cheese varieties, which are treated with lactase enzymes to break down the lactose before consumption. These products are virtually lactose-free, with less than 0.01 grams per serving, ensuring a worry-free experience. Always check labels for "lactose-free" certification, as some cheeses may still contain trace amounts. Additionally, combining cheese with other low-lactose foods can help dilute its impact on your digestive system.

Children and adults alike can benefit from understanding lactose content in cheese, especially in meal planning. For instance, a child’s school lunch could include a slice of cheddar (negligible lactose) instead of a yogurt cup (high lactose), reducing the risk of discomfort. Similarly, older adults with age-related lactose intolerance can still enjoy cheese by choosing harder varieties or lactose-free options. Practical tips include starting with small portions to test tolerance and keeping a food diary to track reactions.

In summary, lactose content in cheese varies widely, offering options for nearly every dietary need. By selecting cheeses based on their lactose levels and using strategies like portion control or enzyme supplements, you can continue to enjoy this versatile food without sacrificing comfort. Whether you’re mildly sensitive or highly intolerant, there’s a cheese out there for you.

Mastering Cheese Bread Storage: Tips for Freshness and Flavor Preservation

You may want to see also

Types of Milk Used

Cheese, a beloved staple in diets worldwide, owes its diversity to the myriad types of milk used in its production. From the creamy richness of cow’s milk to the tangy depth of goat’s milk, each base ingredient imparts distinct flavors, textures, and nutritional profiles. Understanding these differences not only enhances appreciation for the craft but also guides choices based on dietary needs, culinary applications, and personal preferences.

Analytical Perspective: Cow’s milk dominates the cheese industry, accounting for over 90% of global production. Its high fat and protein content—typically 3.5–5% fat and 3.3% protein—creates a versatile base for cheeses ranging from mild mozzarella to sharp cheddar. However, the homogenization of cow’s milk often reduces its complexity, making it a reliable but sometimes predictable choice. In contrast, sheep’s milk, with its 5–8% fat and 5–7% protein, produces richer, denser cheeses like Manchego and Pecorino Romano. This higher fat content not only intensifies flavor but also increases calorie density, making portion control essential for those monitoring intake.

Instructive Approach: For home cheesemakers, selecting milk is the first critical step. Pasteurized cow’s milk is widely available and ideal for beginners, but raw milk (legal in some regions) offers deeper flavors and unique microbial cultures. Goat’s milk, with its lower fat globules and distinct tang, requires precise temperature control—aim for 80–85°F (27–29°C) during coagulation to avoid grainy textures. Buffalo milk, prized for mozzarella di bufala, demands gentle handling due to its 7–8% fat content, which can curdle if overheated. Always use non-ultra-pasteurized milk, as the process denatures proteins essential for curdling.

Comparative Insight: While cow’s milk cheeses often appeal to broader palates, goat’s and sheep’s milk varieties cater to niche tastes. Goat cheese, or chèvre, is lighter in calories (75–100 kcal per ounce) compared to sheep’s milk cheese (110–120 kcal per ounce), making it a preferred option for weight-conscious consumers. However, sheep’s milk’s higher lactose content can be problematic for sensitive individuals, whereas goat’s milk’s smaller fat molecules are easier to digest. For those avoiding dairy, plant-based "cheeses" made from almond, cashew, or coconut milk offer alternatives, though their textures and meltability often differ significantly.

Descriptive Exploration: Buffalo milk, a specialty in regions like Italy and India, yields cheeses with a luxuriously creamy mouthfeel. Its high fat and protein levels create a smooth, elastic curd, perfect for stretching into burrata or shaping into fresh mozzarella. Camel’s milk, though less common, produces cheeses with a uniquely sweet, slightly gamey flavor, often enjoyed in the Middle East and North Africa. Its lower lactose and higher vitamin C content make it a novel option for those with dietary restrictions, though its scarcity and cost limit widespread use.

Practical Takeaway: Choosing the right milk depends on the desired cheese profile and dietary considerations. Cow’s milk is the all-rounder, sheep’s milk the indulgent choice, and goat’s milk the digestive-friendly alternative. For experimentation, start with cow’s milk, then branch out to goat’s or sheep’s milk for more complex flavors. Always consider fat content and lactose levels, especially for health-conscious or intolerant individuals. Whether crafting a classic cheddar or a modern vegan alternative, the milk used is the foundation of every cheese’s identity.

Perfect Cheese Pairings for Smoking Homemade Pepperoni: Top Picks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, cheese is a dairy product as it is made from milk, which comes from animals like cows, goats, or sheep.

Many people with lactose intolerance can tolerate cheese, especially hard cheeses like cheddar or Swiss, as they contain lower levels of lactose compared to milk.

No, cheese made from plant-based milk (e.g., almond, soy, or cashew) is not dairy, as it does not come from animal milk.

Cheese is nutrient-dense, providing protein, calcium, and vitamins, but it also tends to be higher in fat and sodium compared to milk or yogurt.