The question of whether cheese in France is alive sparks curiosity about the intricate relationship between French cheese and its microbial life. Unlike pasteurized cheeses, many traditional French varieties, such as Camembert or Roquefort, are crafted using live cultures and molds that continue to develop during aging. These microorganisms not only contribute to the cheese's distinctive flavors and textures but also remain active, technically keeping the cheese alive in a biological sense. This dynamic process underscores the artisanal nature of French cheesemaking and highlights the country's reverence for preserving centuries-old techniques that celebrate the living, evolving character of its culinary heritage.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cheese Production | France produces over 1,000 varieties of cheese, with an average of 27 kg consumed per person annually (2023 data). |

| Cheese Types | Includes soft (Brie, Camembert), semi-hard (Comté, Cantal), hard (Mimolette, Beaufort), blue (Roquefort, Fourme d'Ambert), and fresh (Chèvre, Boursin). |

| Cultural Significance | Cheese is a staple in French cuisine, often served as part of the traditional "plat de fromage" course in meals. |

| Living Cultures | Many French cheeses, especially raw milk varieties, contain live bacteria and molds (e.g., Penicillium) that contribute to flavor and texture development. |

| Aging Process | Cheese is considered "alive" during aging as microorganisms continue to transform its structure and taste. |

| Regulatory Status | France has strict AOC (Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée) and AOP (Appellation d'Origine Protégée) designations to preserve traditional cheese-making methods. |

| Export | France is one of the largest cheese exporters globally, with cheese being a significant part of its agricultural economy. |

| Consumption Trends | Rising interest in artisanal and organic cheeses, with a focus on sustainability and local production. |

| Health Considerations | Live cultures in cheese can offer probiotic benefits, though raw milk cheeses may pose risks if not properly handled. |

| Symbolism | Cheese is often referred to as "alive" metaphorically in French culture, representing its dynamic role in culinary traditions. |

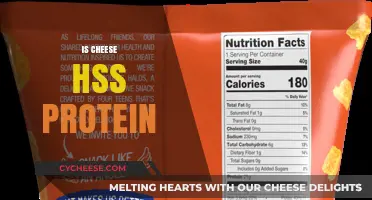

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cheese Aging Process - How does aging affect cheese's microbial activity in France

- Raw Milk Cheese - Are raw milk cheeses in France considered alive due to bacteria

- Cheese Microbiome - What microorganisms in French cheese contribute to its alive status

- Fermentation in Cheese - Does fermentation make French cheese a living food product

- Cheese Ripening - How does ripening keep French cheese biologically active

Cheese Aging Process - How does aging affect cheese's microbial activity in France?

The aging process, or affinage, is a critical phase in cheese production that transforms a simple curd into a complex, flavorful masterpiece. In France, this art is revered, with each cheese variety undergoing a unique aging journey. During affinage, microbial activity plays a starring role, dictating the cheese's texture, aroma, and taste. As cheeses mature, microorganisms like bacteria and molds break down proteins and fats, releasing compounds that contribute to the distinctive characteristics of French cheeses. For instance, the creamy interior of a Camembert owes its existence to the activity of *Penicillium camemberti*, while the pungent aroma of Époisses is a result of *B. linens* metabolism.

Aging duration and conditions significantly influence microbial behavior. Soft cheeses like Brie may age for 4-8 weeks, allowing surface molds to develop a bloomy rind and interior to soften. In contrast, hard cheeses such as Comté can age for 4-24 months, during which time bacterial activity slows, and complex flavor profiles emerge. Temperature and humidity are crucial; a cool, humid environment (10-14°C, 90-95% humidity) encourages mold growth in surface-ripened cheeses, whereas harder cheeses benefit from slightly warmer, drier conditions to promote slower bacterial activity.

Consider the role of salt in this process. During aging, salt acts as a preservative, inhibiting excessive microbial growth while allowing desirable bacteria and molds to flourish. For example, a 2-3% salt concentration in the cheese matrix can create an environment where *P. camemberti* thrives, shaping the characteristic flavor of Camembert. However, too much salt can halt microbial activity, stunting the cheese's development. Thus, precise control of salt levels is essential for guiding the aging process.

Practical tips for home aging include maintaining consistent conditions and monitoring the cheese regularly. For surface-ripened cheeses, wrap them in cheese paper to allow air circulation, and turn them every few days to ensure even mold growth. Hard cheeses should be stored in a cooler, drier environment, ideally in a dedicated cheese cave or refrigerator drawer. If unwanted mold appears, gently wipe it off with a cloth dampened in vinegar. Remember, aging is a delicate balance—patience and attention to detail will yield a cheese that’s truly alive with flavor.

In France, the aging process is not just science but a cultural practice, passed down through generations. Each affineur (cheese ager) brings their expertise, often using traditional methods to coax out the best qualities of the cheese. For enthusiasts, understanding the microbial dynamics of aging offers a deeper appreciation of why French cheeses are celebrated worldwide. Whether you’re crafting your own cheese or simply savoring a slice of aged Comté, recognizing the role of microbial activity transforms the experience from mere consumption to a celebration of living, evolving food.

Peeling Cheese Pumpkins: Necessary Step or Optional Task?

You may want to see also

Raw Milk Cheese - Are raw milk cheeses in France considered alive due to bacteria?

Raw milk cheeses in France are often described as "alive" due to the presence of active bacteria that continue to ferment and age the cheese post-production. Unlike pasteurized cheeses, which undergo heat treatment to eliminate most microorganisms, raw milk cheeses retain their microbial diversity, including lactic acid bacteria and molds. This ongoing bacterial activity contributes to the cheese's evolving texture, flavor, and aroma, making it a dynamic, living product. For instance, a raw milk Camembert will develop a softer rind and richer taste over time, a process driven by these living organisms.

To understand why raw milk cheeses are considered alive, consider the role of bacteria in their production. During aging, bacteria break down lactose into lactic acid, lowering the pH and creating an environment hostile to harmful pathogens. This process not only preserves the cheese but also enhances its complexity. In France, cheeses like Comté, Reblochon, and Roquefort rely on specific bacterial cultures to achieve their signature profiles. The bacteria don’t just exist in the cheese—they actively transform it, a hallmark of a living food.

However, the "alive" label isn’t without controversy. Critics argue that while bacteria are present, the cheese itself isn’t a living organism in the biological sense. The bacteria are microorganisms performing metabolic functions, but the cheese is a matrix of proteins, fats, and other compounds. This distinction matters in scientific terms, yet culturally and culinarily, the dynamic nature of raw milk cheeses justifies their living status. For example, affinage (the art of aging cheese) involves monitoring and manipulating bacterial activity, treating the cheese as a living entity that requires care and attention.

Practical considerations for enjoying raw milk cheeses include proper storage and handling. Keep them in the refrigerator at 4–8°C (39–46°F) and wrap them in wax or parchment paper to allow breathing. Consume within 3–4 weeks of purchase for optimal flavor. Pregnant individuals and those with compromised immune systems should avoid raw milk cheeses due to the risk of pathogens like Listeria. For everyone else, these cheeses offer a unique sensory experience, showcasing the interplay of bacteria and tradition in French cheesemaking.

In conclusion, raw milk cheeses in France are considered alive due to the active bacteria that drive their fermentation and aging. While the scientific definition of "alive" may not apply to the cheese itself, its microbial activity and evolving nature align with the cultural perception of a living product. By understanding and appreciating this process, consumers can better enjoy the complexity and richness of these cheeses, a testament to France’s culinary heritage.

Butter vs. Cheese: Unraveling the Dairy Duo's Differences and Similarities

You may want to see also

Cheese Microbiome - What microorganisms in French cheese contribute to its alive status?

French cheese is a living, breathing ecosystem, teeming with microorganisms that contribute to its unique flavors, textures, and aromas. Among these, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) such as *Lactococcus lactis* and *Streptococcus thermophilus* are the unsung heroes. These bacteria ferment lactose into lactic acid, a process that not only preserves the cheese but also creates its characteristic tang. For example, in Camembert, *Lactococcus lactis* works alongside fungi like *Penicillium camemberti* to produce the creamy interior and edible white rind. Without these microbes, French cheese would lack its signature "alive" quality, both in taste and biological activity.

To understand the microbiome’s role, consider the aging process. In cheeses like Comté or Gruyère, propionic acid bacteria (*Propionibacterium freudenreichii*) produce carbon dioxide gas, creating the distinctive eye formation. These bacteria thrive in the low-oxygen environment of the cheese matrix, metabolizing lactic acid into propionic acid and acetic acid, which contribute to the nutty, complex flavors. Interestingly, the microbial activity continues even after the cheese is packaged, meaning the cheese evolves on your shelf—a literal living food.

Practical tip: To maximize the "alive" experience, store French cheese in the refrigerator at 4–8°C (39–46°F) in a breathable container, like wax paper, to maintain humidity without suffocating the microbes. Avoid plastic wrap, as it traps moisture and can promote unwanted mold growth. For aged cheeses, a wine fridge set to 10–13°C (50–55°F) can slow microbial activity while preserving flavor.

Comparatively, the microbiome in French cheese differs from that of pasteurized or mass-produced varieties, which often lack the diversity of raw-milk cheeses. Raw-milk cheeses, such as Époisses or Reblochon, harbor a richer array of bacteria and fungi, including *Staphylococcus xylosus* and *Debaryomyces hansenii*, which contribute to their robust flavors and surface ripening. Pasteurization eliminates many of these microbes, resulting in a less dynamic product. Thus, the "alive" status of French cheese is intrinsically tied to its microbial diversity and raw-milk origins.

Finally, the microbiome’s role extends beyond flavor—it’s a marker of authenticity. In France, appellations like AOC (Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée) regulate not just the region and production methods but also the microbial cultures used. For instance, Roquefort must contain *Penicillium roqueforti* from specific caves in the region. This ensures the cheese’s microbiome reflects its terroir, making it a living testament to its origin. By preserving these microbial traditions, French cheesemakers keep their craft—and their cheeses—truly alive.

Sheep Milk Cheese vs. Cow's: Which is Healthier for You?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fermentation in Cheese - Does fermentation make French cheese a living food product?

French cheese is a testament to the alchemy of fermentation, a process that transforms simple ingredients into complex, living ecosystems. At its core, fermentation in cheese involves microorganisms—bacteria and fungi—metabolizing lactose and proteins, producing lactic acid, carbon dioxide, and a host of flavor compounds. This microbial activity doesn’t cease once the cheese is formed; it continues, albeit at a slower pace, as the cheese ages. Thus, French cheeses like Camembert, Brie, and Reblochon are not static products but dynamic, evolving entities. The presence of live cultures in these cheeses raises a critical question: does fermentation render them a living food product?

To answer this, consider the role of microorganisms in fermented foods. In raw milk cheeses, which are more common in France due to less stringent pasteurization laws, the microbial flora remains intact. These live bacteria and molds contribute to ongoing enzymatic activity, breaking down proteins and fats, and developing flavors over time. For instance, the white rind of Camembert is alive with *Penicillium camemberti*, a mold that continues to grow and metabolize even after the cheese is packaged. This ongoing biological activity is a hallmark of living foods, as it mirrors the processes found in fresh, unprocessed ingredients. However, the definition of "alive" becomes murky when applied to cheese, as the microorganisms are not self-sustaining in the way a plant or animal is.

From a practical standpoint, treating French cheese as a living product has implications for storage and consumption. To preserve its vitality, cheese should be stored in conditions that allow microbial activity to continue—ideally, in a cool, humid environment with proper ventilation. Wrapping cheese in wax or plastic can stifle this process, halting the development of flavors. For optimal enjoyment, allow cheese to breathe at room temperature for 30–60 minutes before serving. This reawakens the dormant microorganisms, enhancing texture and aroma. Pairing fermented cheeses with prebiotic-rich foods like apples or nuts can also amplify their probiotic benefits, as the fibers feed the beneficial bacteria in the gut.

Critics argue that pasteurized cheeses, which dominate the global market, cannot be considered living due to the absence of active microorganisms. Yet, even in pasteurized French cheeses, the fermentation process leaves behind metabolic byproducts that continue to evolve. For example, the amino acids and organic acids produced during fermentation react with each other over time, creating new flavor profiles. This chemical transformation, though not biological, underscores the dynamic nature of cheese. Thus, while pasteurized cheeses may lack live cultures, they still exhibit characteristics of a living food through their ongoing chemical changes.

In conclusion, fermentation undeniably imbues French cheese with qualities that resemble living systems. The presence of active microorganisms in raw milk cheeses and the ongoing chemical reactions in pasteurized varieties both contribute to their dynamic nature. Whether this qualifies cheese as "alive" depends on one’s definition of life. Practically, however, treating cheese as a living product—through proper storage, handling, and consumption—enhances its sensory and nutritional qualities. In the world of French cheese, fermentation is not just a process; it’s a philosophy that celebrates the interplay of time, biology, and craftsmanship.

Mastering Cheese Dip Storage: Tips to Keep It Fresh and Tasty

You may want to see also

Cheese Ripening - How does ripening keep French cheese biologically active?

French cheese is a living, breathing entity, thanks to the intricate process of ripening. This transformation from fresh curds to complex, flavorful wheels is a delicate dance of microbiology, where time, temperature, and humidity orchestrate a symphony of enzymatic activity. At the heart of this process lies the concept of biological activity—a state of dynamic change that keeps French cheese alive in every sense.

Ripening, or affinage, is not merely aging; it’s a controlled environment where beneficial bacteria and molds thrive, breaking down proteins and fats into amino acids, fatty acids, and aromatic compounds. This metabolic activity is what keeps the cheese biologically active. For instance, in a Camembert, the white *Penicillium camemberti* rind consumes lactose and proteins, releasing ammonia and carbon dioxide, which contribute to its distinctive flavor and texture. Similarly, in a Comté, bacterial cultures like *Lactobacillus* and *Propionibacterium* produce lactic and propionic acids, creating its nutty, sweet profile. Without ripening, these cheeses would remain inert, lacking the depth and complexity that define their character.

The key to maintaining biological activity lies in precise conditions. Temperature, for example, must be carefully regulated—a mere 2°C deviation can halt microbial activity or accelerate spoilage. Most soft cheeses ripen between 10–14°C, while harder cheeses like Cantal require 12–15°C. Humidity is equally critical; a relative humidity of 90–95% prevents the cheese from drying out while allowing molds to flourish. Artisans often turn cheeses regularly to ensure even moisture distribution and microbial growth. For home enthusiasts, a wine fridge set to 12°C and a sealed container with a damp cloth can mimic these conditions, though results may vary.

One fascinating aspect of ripening is the role of enzymes. During cheese making, rennet or microbial transglutaminase coagulates milk, but it’s the endogenous enzymes from the milk and added cultures that drive ripening. Lipases break down fats into free fatty acids, contributing to sharpness, while proteases degrade proteins into peptides and amino acids, enhancing umami. In blue cheeses like Roquefort, *Penicillium roqueforti* produces unique enzymes that create its signature veins and pungency. These enzymatic reactions are a testament to the cheese’s living nature, as they continue to evolve until the cheese is consumed.

Practical tips for appreciating this biological activity include observing the cheese’s texture and aroma over time. A properly ripened Brie should yield slightly to pressure and emit a mushroomy scent, while an overripe cheese may develop an ammonia-like odor. Pairing wines with ripened cheeses can also highlight their active nature—a crisp Chardonnay complements the lactic tang of a Chèvre, while a bold Bordeaux balances the earthy complexity of an aged Gruyère. By understanding ripening, one not only preserves the cheese’s vitality but also elevates its sensory experience.

Discover the Perfect Quesadilla Cheese: Types, Melts, and Flavors

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese itself is not alive, as it is a dairy product made from milk through fermentation and aging processes. However, it contains live bacteria and molds that contribute to its flavor and texture, especially in raw milk cheeses.

Not all French cheeses contain live cultures. Many undergo pasteurization, which kills bacteria, while others, like raw milk cheeses (e.g., Camembert or Brie), retain live cultures.

The live bacteria in French cheese are generally safe for most people, as they are part of the fermentation process. However, individuals with weakened immune systems or pregnant women are advised to avoid raw milk cheeses due to potential risks.

Yes, the live bacteria and molds in raw milk French cheeses contribute to their unique flavors, aromas, and textures. These microorganisms continue to develop the cheese even after it is made, enhancing its complexity over time.