Cheese is often described as old milk, but this oversimplifies the intricate process of its creation. While cheese does originate from milk, it undergoes a transformative journey involving coagulation, curdling, and aging, which fundamentally alters its texture, flavor, and nutritional profile. The milk, typically from cows, goats, or sheep, is treated with enzymes like rennet or bacterial cultures to separate it into curds and whey. These curds are then pressed, salted, and aged, resulting in the diverse array of cheeses we know today. Thus, while cheese shares its base ingredient with milk, it is a distinct product, shaped by craftsmanship and time rather than mere aging.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Cheese is a dairy product made from milk, but it is not simply "old milk." It undergoes a complex process of curdling, draining, and aging. |

| Ingredients | Milk (cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo), bacteria cultures, rennet (or alternatives), salt |

| Process | 1. Milk is acidified with bacteria cultures 2. Rennet is added to coagulate milk into curds and whey 3. Curds are cut, stirred, and heated 4. Whey is drained, and curds are pressed 5. Cheese is salted and aged |

| Aging | Cheese is aged for varying periods (days to years) to develop flavor, texture, and complexity |

| Nutritional Differences | Cheese has higher protein, fat, and calorie content compared to milk due to concentration during processing |

| Shelf Life | Cheese has a longer shelf life than milk due to reduced moisture content and aging |

| Texture | Cheese ranges from soft (brie) to hard (parmesan), unlike liquid milk |

| Flavor | Cheese develops unique flavors during aging, distinct from fresh milk |

| Lactose Content | Most cheeses have lower lactose content than milk due to bacterial breakdown during production |

| Conclusion | Cheese is a transformed product of milk, not just "old milk," with distinct characteristics resulting from its production and aging process |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cheese-making process: Coagulating milk, separating curds, aging transforms milk into cheese

- Aging and flavor: Longer aging intensifies cheese flavor and texture

- Milk types used: Cow, goat, sheep milk each yield distinct cheese varieties

- Preservation method: Cheese extends milk's shelf life through fermentation and curing

- Nutritional changes: Aging alters milk's protein, fat, and nutrient composition in cheese

Cheese-making process: Coagulating milk, separating curds, aging transforms milk into cheese

Cheese begins as milk, but the transformation is far from a simple aging process. At its core, cheese-making is a precise science that hinges on three critical steps: coagulating milk, separating curds, and aging. Each phase alters the milk’s structure and composition, turning it into a solid, flavorful product. Coagulation, the first step, involves adding rennet or acid to milk, causing proteins to clump together. This is not just a random reaction; the dosage of rennet matters—typically 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon per gallon of milk—to ensure proper curd formation without over-coagulation. Without this step, milk remains liquid, and cheese cannot take shape.

Once coagulated, the milk separates into curds (solid) and whey (liquid). This separation is both mechanical and chemical, requiring gentle cutting and stirring to release whey while preserving curd integrity. The curds are then heated and pressed, a process that determines the cheese’s texture. For example, soft cheeses like mozzarella are lightly pressed, while hard cheeses like cheddar undergo higher pressure and heat. This stage is where the milk’s transformation becomes tangible, as the curds lose moisture and begin to resemble cheese.

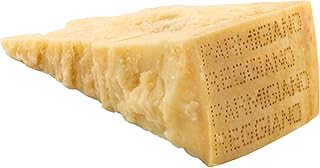

Aging is where cheese truly diverges from its milk origins. During this phase, enzymes and bacteria break down proteins and fats, developing complex flavors and textures. Aging times vary widely: fresh cheeses like ricotta age for days, while Parmesan matures for years. Temperature and humidity control are critical here—ideally 50-55°F and 85% humidity for most cheeses. This step is less about preservation and more about crafting depth, as the milk’s original characteristics are refined into something entirely new.

The journey from milk to cheese is a testament to human ingenuity in manipulating natural processes. While cheese does start as milk, it is not merely "old milk" but a product of deliberate transformation. Each step—coagulation, curd separation, and aging—serves a unique purpose, turning a perishable liquid into a durable, diverse food. Understanding this process not only demystifies cheese but also highlights the artistry behind its creation.

Are Cheese Curds Unhealthy? Uncovering the Truth About This Snack

You may want to see also

Aging and flavor: Longer aging intensifies cheese flavor and texture

Cheese is, in essence, transformed milk. But the magic lies not just in the transformation but in the waiting game that follows. Aging, a process as old as cheese itself, is the secret weapon behind the complex flavors and textures that elevate cheese from a simple dairy product to a culinary masterpiece.

Think of it like this: a young cheese is like a teenager – full of potential but still finding its footing. Its flavors are mild, its texture supple. Give it time, though, and that same cheese matures into a sophisticated adult, its personality deepening with age.

The science behind this transformation is fascinating. As cheese ages, moisture evaporates, concentrating the proteins and fats. This concentration intensifies the existing flavors and allows new ones to develop through the breakdown of proteins and the activity of bacteria and molds. Imagine a cheddar: a young cheddar is mild and creamy, but a cheddar aged for 12 months or more develops a sharp, nutty flavor and a crumbly texture.

A year-long nap for a Parmigiano-Reggiano results in a hard, granular cheese with a complex, savory flavor profile that explodes on the palate.

The aging process isn't just about time; it's about creating the perfect environment. Temperature and humidity are meticulously controlled to encourage the desired bacterial growth and mold development. Some cheeses are washed with brine or wine, adding further layers of complexity. Others are allowed to develop a natural rind, which protects the cheese and contributes to its unique character.

Think of a smelly French cheese like Epoisses – its pungent aroma and creamy interior are the result of a specific aging process that involves regular washing with Marc de Bourgogne, a local spirit.

Understanding the impact of aging allows you to appreciate the nuances of different cheeses. A young, fresh cheese like mozzarella is perfect for melting on a pizza, while an aged Gouda, with its caramelized notes and crystalline texture, is best enjoyed on its own or paired with a bold red wine.

Exploring the Mystery: Where is the Cheese Cave Located?

You may want to see also

Milk types used: Cow, goat, sheep milk each yield distinct cheese varieties

Cheese is indeed old milk, transformed through the alchemy of fermentation and coagulation. But not all milk is created equal, and the type of milk used—cow, goat, or sheep—dictates the flavor, texture, and character of the cheese. Cow’s milk, the most common base, produces classics like Cheddar and Mozzarella, known for their mild, buttery profiles and versatility. Goat’s milk, with its higher acidity and distinct tang, yields cheeses like Chèvre and Gouda, prized for their bright, slightly earthy notes. Sheep’s milk, richer in fat and protein, creates indulgent varieties such as Manchego and Pecorino, celebrated for their nutty, robust flavors and crumbly textures. Each milk type brings its own chemistry to the aging process, resulting in a diverse spectrum of cheeses that cater to every palate.

For the home cheesemaker or curious enthusiast, understanding milk types is the first step in crafting or selecting cheese. Cow’s milk, widely available and affordable, is ideal for beginners experimenting with staples like Swiss or Provolone. Goat’s milk, though pricier, offers a unique challenge due to its lower fat content, requiring precise temperature control during curdling. Sheep’s milk, the most luxurious of the three, demands careful handling to preserve its richness but rewards with complex, age-worthy cheeses. A practical tip: when substituting one milk for another, adjust rennet dosage accordingly—sheep’s milk, for instance, coagulates faster and requires less rennet than cow’s milk.

From a nutritional standpoint, milk type also influences cheese’s health profile. Sheep’s milk cheeses, like Feta, pack a higher calorie and protein punch, making them satiating in small portions. Goat’s milk cheeses are often easier to digest due to their smaller fat globules and lower lactose content, a boon for those with mild dairy sensitivities. Cow’s milk cheeses, while more calorie-dense, provide a balanced mix of vitamins and minerals, particularly calcium and phosphorus. Pairing cheeses with complementary foods—such as sheep’s milk Manchego with quince paste or goat’s milk Chèvre with honey—enhances both flavor and nutrient absorption.

Comparatively, the aging potential of cheeses varies dramatically by milk type. Sheep’s milk cheeses, with their high fat and protein content, age beautifully, developing deep, crystalline textures over months or even years. Cow’s milk cheeses, like Parmesan, also benefit from long aging, gaining complexity and hardness. Goat’s milk cheeses, however, are typically enjoyed young to preserve their fresh, tangy qualities, though exceptions like aged Gouda showcase their versatility. For optimal storage, wrap sheep’s and cow’s milk cheeses in wax paper to breathe, while goat’s milk cheeses fare better in airtight containers to retain moisture.

In culinary applications, the choice of milk type can elevate a dish from ordinary to extraordinary. Cow’s milk cheeses like Mozzarella melt seamlessly into pizzas and pastas, providing creamy, stretchy textures. Goat’s milk cheeses, such as Bucheron, add a zesty contrast to salads or charcuterie boards. Sheep’s milk cheeses, like Pecorino Romano, grate effortlessly over roasted vegetables or soups, imparting a savory depth. A pro tip: when substituting cheeses, consider the milk type’s inherent qualities—a goat’s milk cheese won’t melt like cow’s milk, but its tang can brighten a dish in a different, equally delightful way.

Are Philly Cheesesteaks Italian? Unraveling the Origins of a Classic Sandwich

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preservation method: Cheese extends milk's shelf life through fermentation and curing

Cheese is, in essence, milk transformed through the alchemy of fermentation and curing. This process not only alters its texture and flavor but also dramatically extends its shelf life, turning a perishable liquid into a durable solid. Fresh milk spoils within days, but cheese can last weeks, months, or even years, depending on the variety and aging process. This transformation is a testament to human ingenuity in food preservation, rooted in techniques that date back thousands of years.

Fermentation is the first step in this preservation journey. When milk is exposed to specific bacteria or molds, these microorganisms consume lactose (milk sugar) and produce lactic acid. This acidification lowers the milk’s pH, creating an environment hostile to spoilage bacteria. For example, in the production of cheddar, *Lactococcus lactis* bacteria are added to pasteurized milk, causing it to curdle and form a solid mass. This curd is then cut, heated, and pressed to expel whey, the liquid byproduct. The remaining solid is the foundation of cheese, now far more stable than the milk it came from.

Curing takes this process further, enhancing preservation while developing flavor and texture. During curing, cheese is aged under controlled conditions of temperature and humidity. Hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano are aged for 12 to 36 months, during which moisture evaporates, and complex flavors emerge. Soft cheeses, such as Brie, cure for a shorter period, typically 4 to 6 weeks, retaining more moisture but still achieving a longer shelf life than fresh milk. Salt is often added during curing, acting as a preservative by drawing out moisture and inhibiting bacterial growth. For instance, feta cheese is brined, which not only preserves it but also contributes to its distinctive tangy taste.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers underscore the importance of precision in fermentation and curing. Maintaining a consistent temperature is critical; fluctuations can disrupt bacterial activity or encourage unwanted mold growth. For fermentation, a temperature range of 72°F to 75°F (22°C to 24°C) is ideal for most cheeses. During curing, humidity levels must be monitored—hard cheeses require lower humidity (around 60–70%) to prevent mold, while soft cheeses thrive in higher humidity (85–95%). Regularly flipping and brushing the cheese prevents uneven drying and mold formation.

The takeaway is clear: cheese is not just "old milk" but a product of deliberate, science-backed preservation methods. Fermentation and curing transform milk’s perishability into longevity, creating a food that sustains across seasons and generations. Whether crafting cheese at home or appreciating its complexity in a meal, understanding these processes deepens our respect for this ancient craft.

Can Bacon Strips with Cheese Harm Your Dog's Health?

You may want to see also

Nutritional changes: Aging alters milk's protein, fat, and nutrient composition in cheese

Cheese is indeed a transformed version of milk, but the aging process does more than just preserve it—it fundamentally alters its nutritional profile. As milk ages into cheese, its protein, fat, and nutrient composition undergo significant changes, influenced by factors like microbial activity, moisture loss, and enzymatic reactions. For instance, the protein content in cheese becomes more concentrated due to the removal of whey during production, making it a denser source of essential amino acids compared to fresh milk.

Consider the fat content: during aging, lipases (enzymes that break down fats) can modify the structure of milk fats, creating unique flavor compounds while also altering the fatty acid profile. Hard cheeses like Parmesan, aged for over a year, have a higher proportion of saturated fats but also contain beneficial fatty acids like conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), which has been linked to anti-inflammatory effects. In contrast, softer cheeses retain more moisture and have a fat composition closer to that of the original milk, though still transformed by microbial cultures.

Nutrient-wise, aging can both enhance and diminish certain vitamins and minerals. For example, vitamin B12 and calcium become more concentrated in cheese due to the removal of water, making a 30g serving of cheddar provide about 20% of the daily calcium requirement. However, water-soluble vitamins like vitamin C are largely lost during the cheese-making process. Additionally, the fermentation involved in aging increases the bioavailability of certain minerals, such as phosphorus, by breaking down compounds that inhibit absorption.

Practical tip: To maximize nutritional benefits, pair aged cheeses with foods rich in lost nutrients. For instance, serve a slice of aged Gouda (high in vitamin K2, which supports bone health) with an orange (rich in vitamin C) to compensate for the vitamin C deficiency in cheese. Similarly, opt for full-fat varieties to benefit from the CLA content, but monitor portion sizes to balance calorie intake.

In summary, cheese is not just old milk—it’s a nutritionally evolved product. Understanding how aging reshapes its protein, fat, and nutrient composition allows you to make informed choices, whether you’re seeking a concentrated protein source, specific fatty acids, or enhanced mineral absorption. Treat cheese as a dynamic ingredient, not just a dairy relic, and tailor its consumption to meet your dietary needs.

Exploring the Truth: Are Cheese Caves Real or Just a Myth?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese is not simply old milk; it is a processed dairy product made by curdling milk with enzymes or acids, separating the curds from the whey, and then aging or treating the curds to develop flavor and texture.

Cheese can spoil, but it has a longer shelf life than milk due to its lower moisture content and the preservation methods used during production. However, mold or off odors indicate it has gone bad.

Cheese and milk have different nutritional profiles. Cheese is higher in fat and protein but lower in lactose, making it easier to digest for some. Whether it’s "healthier" depends on individual dietary needs and portion control.