The question of whether cheese is truly binding has sparked considerable debate among nutritionists, digestive health experts, and food enthusiasts alike. Often associated with causing constipation, cheese’s binding reputation stems from its low fiber content and high fat levels, which can slow down digestion. However, the extent to which cheese affects bowel movements varies widely depending on factors such as individual tolerance, the type of cheese consumed, and overall diet. While some people may experience firmer stools after eating cheese, others might not notice any significant changes. Understanding the science behind cheese’s impact on digestion requires examining its nutritional composition, how it interacts with the gut, and the role of personal dietary habits in shaping its effects.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Myth vs. Reality | Cheese is often believed to be constipating, but this is a myth for most people. |

| Lactose Content | Hard cheeses (Cheddar, Parmesan) have low lactose, unlikely to cause constipation. Soft cheeses (Mozzarella, Brie) have more lactose, potentially affecting lactose intolerant individuals. |

| Fat Content | High-fat cheeses can slow digestion slightly, but not significantly enough to cause binding. |

| Individual Variability | Some people may be more sensitive to cheese and experience constipation, but this is not a universal effect. |

| Fiber Intake | A diet low in fiber combined with high cheese consumption might contribute to constipation. |

| Hydration | Dehydration can worsen constipation, so ensure adequate water intake when consuming cheese. |

| Overall Diet | A balanced diet with sufficient fiber and fluids is key to preventing constipation, regardless of cheese intake. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cheese's Digestive Impact: How does cheese affect digestion and potential constipation in different individuals

- Lactose Intolerance Role: Does lactose in cheese contribute to digestive discomfort or binding effects

- Fat Content Influence: High-fat cheeses: Do they slow digestion and cause binding sensations

- Cheese Type Variations: Do hard, soft, or processed cheeses differ in digestive binding effects

- Individual Tolerance Factors: How do age, health, and diet influence cheese's binding properties

Cheese's Digestive Impact: How does cheese affect digestion and potential constipation in different individuals?

Cheese, a beloved staple in many diets, often sparks debate about its digestive effects. While some claim it’s binding and can lead to constipation, others report no issues. The truth lies in the interplay of cheese’s composition—fat, protein, and lactose content—and individual factors like lactose intolerance, gut health, and portion size. For instance, hard cheeses like cheddar are lower in lactose, making them easier to digest for those with mild intolerance, while softer cheeses like brie may pose more challenges. Understanding these nuances is key to determining how cheese impacts your digestion.

Consider the role of fat content in cheese digestion. High-fat cheeses, such as blue cheese or cream cheese, slow down gastric emptying, which can lead to feelings of fullness and potentially delayed bowel movements. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean constipation for everyone. For individuals with a healthy gut microbiome, the slower transit time may simply result in a more gradual digestive process. Conversely, those with pre-existing digestive issues, like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), may find high-fat cheeses exacerbate symptoms. Moderation is crucial; limiting portions to 1–2 ounces per serving can help mitigate potential discomfort.

Lactose intolerance is another critical factor in cheese’s digestive impact. While hard and aged cheeses contain minimal lactose due to the fermentation process, softer or fresher cheeses retain more of this sugar. For lactose-intolerant individuals, even small amounts of lactose can trigger bloating, gas, and constipation. If you suspect lactose is the culprit, opt for lactose-free cheese alternatives or take a lactase enzyme supplement before consuming dairy. Additionally, pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or vegetables can aid digestion and counteract potential binding effects.

Age and overall health also play a role in how cheese affects digestion. Older adults, for example, often experience slower digestion due to reduced gut motility, making high-fat or lactose-containing cheeses more likely to cause constipation. Similarly, individuals with conditions like hypothyroidism or diabetes may have slower digestive systems, amplifying cheese’s binding potential. For these groups, choosing low-fat, low-lactose cheeses and staying hydrated can help maintain regularity. Incorporating probiotics, such as those found in yogurt or kefir, can further support gut health and offset any negative effects.

Finally, practical tips can make cheese consumption more digestion-friendly. Pairing cheese with fermented foods like sauerkraut or kimchi introduces beneficial bacteria that aid in breaking down dairy. Staying hydrated is essential, as water softens stool and promotes bowel movements. For those prone to constipation, combining cheese with high-fiber snacks like apples or nuts can create a balanced digestive environment. Experimenting with different types of cheese and monitoring your body’s response will help you identify which varieties work best for your unique digestive system. Cheese doesn’t have to be off-limits—it’s about mindful choices and listening to your body.

Revive Your Cheese Log: Quick Fixes for Over-Seasoned Mistakes

You may want to see also

Lactose Intolerance Role: Does lactose in cheese contribute to digestive discomfort or binding effects?

Cheese, a staple in many diets, often raises questions about its impact on digestion, particularly for those with lactose intolerance. Lactose, a sugar found in milk and dairy products, requires the enzyme lactase for proper digestion. When lactase is deficient, undigested lactose can ferment in the gut, leading to symptoms like bloating, gas, and diarrhea. However, cheese typically contains lower lactose levels compared to milk, as much of it is removed during the cheesemaking process. This raises the question: does the lactose in cheese significantly contribute to digestive discomfort or binding effects in lactose-intolerant individuals?

To address this, consider the lactose content in different cheeses. Hard cheeses like cheddar, Parmesan, and Swiss contain less than 1 gram of lactose per serving (1.5 ounces), making them generally well-tolerated. Soft cheeses like ricotta or cottage cheese, however, retain more lactose, often exceeding 3 grams per serving, which may trigger symptoms in sensitive individuals. Aged cheeses, due to their prolonged fermentation, have even lower lactose levels, sometimes as little as 0.1 grams per serving. For those with lactose intolerance, monitoring portion sizes and choosing harder, aged varieties can minimize discomfort while still enjoying cheese.

The binding effect often associated with cheese is more likely linked to its fat and protein content rather than lactose. High-fat cheeses slow gastric emptying, which can lead to a feeling of fullness or constipation in some individuals. However, this is distinct from lactose-induced digestive issues. For lactose-intolerant individuals, the key is not to avoid cheese entirely but to select low-lactose options and consume them in moderation. Pairing cheese with lactase supplements or lactose-free products can also help mitigate potential discomfort.

Practical tips for managing lactose intolerance while enjoying cheese include starting with small portions to gauge tolerance, opting for harder or aged varieties, and incorporating cheese into meals rather than consuming it alone. For example, a 30-gram serving of aged cheddar with a meal is less likely to cause issues than a 100-gram portion of ricotta on its own. Additionally, individuals over 50, who are more prone to lactase deficiency, may benefit from gradually introducing low-lactose cheeses into their diet. By understanding the lactose content and its role, lactose-intolerant individuals can navigate cheese consumption without sacrificing digestive comfort.

Does Sonoma Jack's Cheese Require Refrigeration? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Fat Content Influence: High-fat cheeses: Do they slow digestion and cause binding sensations?

High-fat cheeses, such as cheddar, gouda, and blue cheese, often contain upwards of 30% fat by weight. This elevated fat content can significantly impact digestion, potentially leading to a binding sensation. When consumed, dietary fats slow gastric emptying, the process by which food leaves the stomach and enters the small intestine. This delay occurs because fats require more time to break down and emulsify, triggering a prolonged release of stomach contents. For individuals prone to constipation or those with sensitive digestive systems, this slowed transit time can exacerbate feelings of fullness, discomfort, or even temporary constipation.

Consider the mechanism at play: fats stimulate the release of cholecystokinin (CCK), a hormone that signals satiety and slows digestion. While this can be beneficial for appetite control, it also means high-fat cheeses may linger in the stomach longer than lower-fat alternatives. For example, a 30g serving of cheddar (9g fat) could take 3–4 hours to fully exit the stomach, compared to 2–3 hours for the same portion of part-skim mozzarella (6g fat). Pairing high-fat cheeses with fiber-rich foods, like whole-grain crackers or raw vegetables, can mitigate this effect by promoting stool bulk and regularity.

However, the binding sensation isn’t universally negative. For some, the slower digestion induced by high-fat cheeses can provide a sense of prolonged fullness, reducing snacking and aiding portion control. Athletes or those with high caloric needs may find this particularly advantageous. The key lies in moderation and awareness of individual tolerance. Limiting high-fat cheese intake to 1–2 servings per day (30–60g) and balancing it with hydrating, fiber-rich foods can minimize discomfort while retaining nutritional benefits like calcium and protein.

A comparative analysis reveals that not all high-fat cheeses affect digestion equally. Cream cheese, despite its fat content (33g per 100g), often contains stabilizers and lower protein levels, which may reduce its binding potential compared to aged cheeses like parmesan (32g fat per 100g). Similarly, soft, high-fat cheeses like brie may be better tolerated due to their higher moisture content. Experimenting with portion sizes and cheese varieties can help identify which options align with personal digestive comfort.

In practical terms, individuals experiencing binding sensations from high-fat cheeses can adopt simple strategies. Hydration is critical, as water aids fat emulsification and stool softening. Aim for 8–10 glasses of fluid daily, particularly when consuming fatty meals. Additionally, pairing cheese with probiotic-rich foods like yogurt or kefir can support gut health, enhancing digestion efficiency. For those over 50 or with pre-existing digestive conditions, consulting a dietitian to tailor cheese choices and portions can prevent discomfort while enjoying this nutrient-dense food.

Cat-Approved Snack: Cheese Puffs with a Feline Package Design

You may want to see also

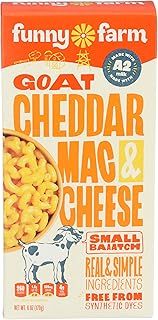

Explore related products

$8.99 $9.99

Cheese Type Variations: Do hard, soft, or processed cheeses differ in digestive binding effects?

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, often faces scrutiny for its perceived binding effects on digestion. However, not all cheeses are created equal. Hard cheeses, like Parmesan or Cheddar, contain lower lactose levels due to their prolonged aging process, which may reduce their binding potential for lactose-intolerant individuals. Conversely, soft cheeses such as Brie or Camembert retain more lactose, potentially exacerbating digestive discomfort in sensitive populations. Processed cheeses, often high in additives and lower in natural enzymes, can vary widely in their digestive impact, depending on individual tolerance to artificial ingredients.

To understand these differences, consider the role of moisture content and aging. Hard cheeses have less water, concentrating proteins and fats while reducing lactose. This makes them easier to digest for some, particularly in moderate portions—around 30–50 grams per serving. Soft cheeses, with higher moisture levels, retain more lactose and whey proteins, which can slow digestion and contribute to a binding effect, especially in larger quantities. For example, consuming more than 100 grams of soft cheese in one sitting may increase the likelihood of constipation in susceptible individuals. Processed cheeses, often emulsified for consistency, can introduce stabilizers and preservatives that disrupt gut motility, though their impact varies based on formulation.

From a practical standpoint, those concerned about digestive binding should experiment with portion sizes and cheese types. Start with small servings of hard cheeses to gauge tolerance, gradually increasing if no discomfort occurs. For soft cheeses, pair them with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or vegetables to counteract potential binding effects. Avoid processed cheeses if you notice adverse reactions to additives, opting instead for natural varieties. Age is also a factor: older adults or those with pre-existing digestive conditions may find hard cheeses more tolerable due to their lower lactose content.

Comparatively, the digestive impact of cheese types underscores the importance of personalization. While hard cheeses may suit lactose-sensitive individuals, soft cheeses can be enjoyed in moderation with dietary adjustments. Processed cheeses remain a wildcard, requiring individual assessment. For instance, a 30-year-old with mild lactose intolerance might tolerate 40 grams of aged Gouda daily but experience binding effects from 50 grams of processed American cheese. Tracking symptoms and consulting a dietitian can help tailor cheese choices to specific digestive needs.

In conclusion, the binding effects of cheese are not universal but depend on type, portion, and individual factors. Hard cheeses generally pose less risk due to lower lactose, while soft and processed varieties require careful consideration. By understanding these variations and adjusting intake accordingly, cheese can remain a digestively friendly part of a balanced diet. Practical tips, such as monitoring portion sizes and pairing cheeses with fiber, can further mitigate potential discomfort, ensuring that cheese lovers can enjoy their favorite varieties without digestive repercussions.

Cheese and Vitamins: Uncovering Nutritional Benefits in Your Favorite Dairy

You may want to see also

Individual Tolerance Factors: How do age, health, and diet influence cheese's binding properties?

Cheese's binding properties aren't a one-size-fits-all phenomenon. Individual tolerance plays a pivotal role, with age, health, and diet acting as key modulators. Understanding these factors can help you navigate cheese's effects on digestion and overall well-being.

Age: A Shifting Landscape of Enzyme Activity

As we age, our bodies produce less lactase, the enzyme responsible for breaking down lactose, a sugar found in milk and dairy products. This decline in lactase production, known as lactase non-persistence, affects roughly 65% of the global population. For these individuals, consuming cheese, especially fresh varieties with higher lactose content, can lead to digestive discomfort, including bloating, gas, and diarrhea. Older adults, therefore, may experience cheese's binding effects more pronouncedly due to reduced lactose digestion.

Hard, aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan contain significantly less lactose, making them generally better tolerated by those with lactose intolerance.

Health Conditions: When Underlying Issues Amplify Effects

Pre-existing health conditions can significantly influence how cheese interacts with your digestive system. Individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) often find that dairy products, including cheese, exacerbate symptoms like bloating and abdominal pain. This is due to the fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) present in dairy, which can trigger gut sensitivity.

Additionally, those with gastrointestinal disorders like Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis may experience worsened symptoms after consuming cheese due to its potential to irritate the intestinal lining.

Dietary Habits: Context Matters

The overall composition of your diet plays a crucial role in how cheese affects your digestion. A diet high in fiber can help mitigate the binding effects of cheese by promoting regular bowel movements and preventing constipation. Conversely, a diet low in fiber and high in processed foods can exacerbate cheese's constipating potential.

Practical Tips:

- Experiment with Cheese Types: Opt for hard, aged cheeses if lactose intolerance is a concern.

- Monitor Portion Sizes: Start with small servings and gradually increase to assess tolerance.

- Pair with Fiber-Rich Foods: Enjoy cheese with whole grains, fruits, or vegetables to promote healthy digestion.

- Listen to Your Body: Pay attention to how different cheeses affect you and adjust your intake accordingly.

Understanding your individual tolerance factors empowers you to make informed choices about incorporating cheese into your diet. By considering age, health, and dietary habits, you can navigate cheese's binding properties and enjoy its culinary delights without discomfort.

Mastering Radahn: Cheese Tactics in Shadow of the Erdtree

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese can be binding for some people due to its low fiber content and high fat and protein levels, which can slow digestion. However, its effect varies depending on individual tolerance and the type of cheese consumed.

Cheese is considered binding because it lacks fiber and contains high amounts of fat and protein, which can slow the movement of food through the digestive tract. This can lead to firmer stools and potential constipation in some individuals.

Regularly consuming large amounts of cheese, especially without adequate fiber and water intake, can contribute to constipation. Moderation and balancing cheese with fiber-rich foods can help prevent digestive issues.